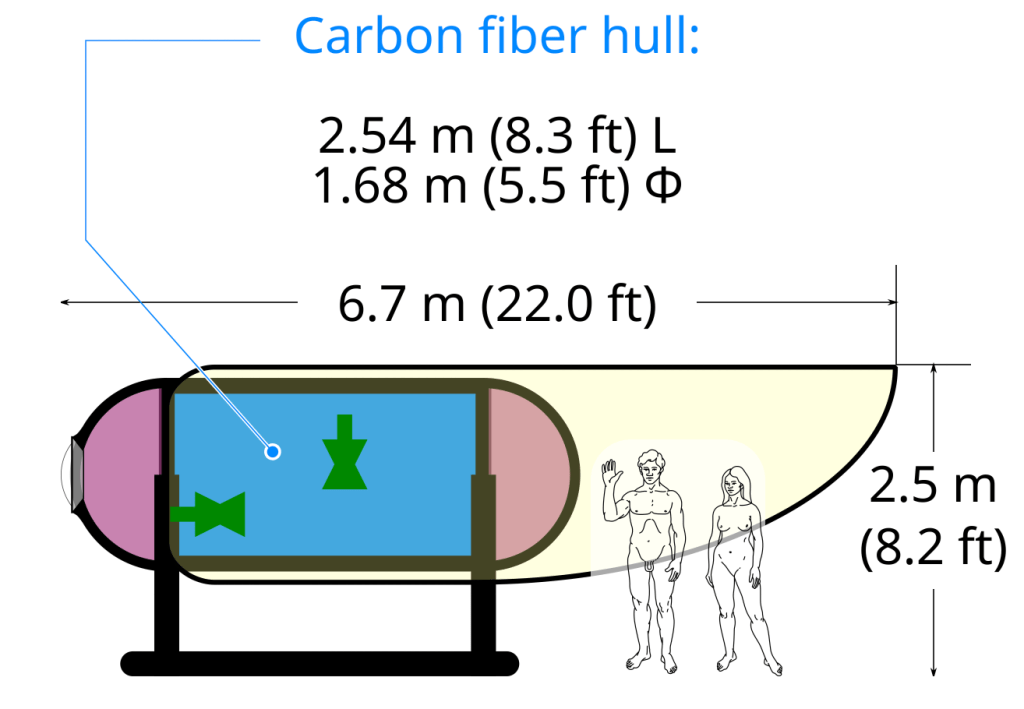

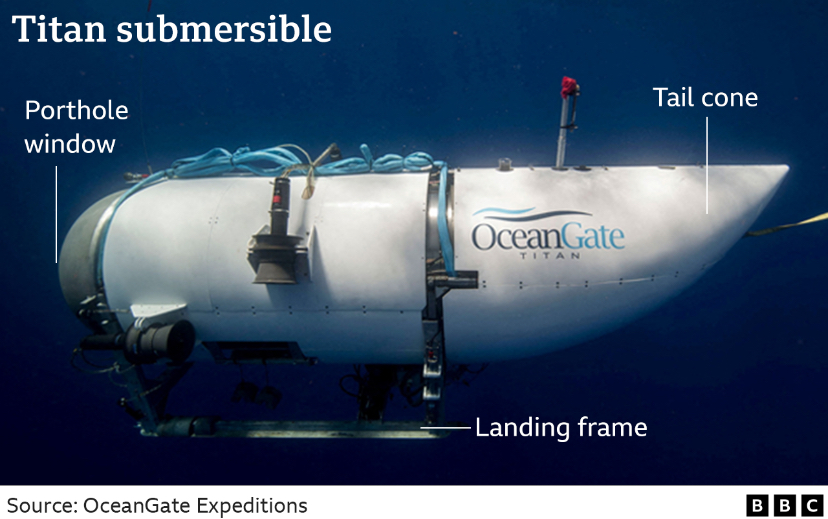

Urgent hopes to discover the five passengers tragically killed in the lost submersible off the shores of Newfoundland spread with compelling urgency across global media after the Titan Submersible lost contact with those on land. The disappearance of the crudely-designed submersible that Stockton Rush had claimed would offer a voyage to the ruins of the great tragedy of the twentieth century had exploded from the undersea pressure it endured as it descended to the wreck of the Titanic. The voyage had tempted fate as a disaster in the making. fell off of the global map, venturing deep, deep underseas. The craft’s tragic disappearance quickly dominated global media with an odd urgency of portentousness fed by the image of a renegade entrepreneur who seemed, despite his worldly wealth, to be courting disaster, in braving a new frontier of an improbably untouched wilderness. Although no bodies or skeletons remain on the Titanic’s undersea ruins, the loss of life that was itself transformed by newspapers into a traumatic site of global mourning and tragedy was eerily replicated. What Rush and his company, OceanGate, had promoted as an ability to transcend a classic icon of death, or at least carry paying observers to see at first hand, was a project he pushed even while making the deep diving sub out of experimental materials, without any third-party oversight, out of the robustt sounding materials as carbon fibre and titanium.

The wreck of the Titanic is an icon of unbearable loss, the scale of whose unexpected destruction is an icon of loss that continues to attract curiosity as it still fails comprehension for many as an epic tragedy. The promise to revisit the unspeakable pain of ruins long lying on the ocean’s floor was perhaps a form of triumphal return. It had been promised to a once-in-a-lifetime underwater voyage, by new technologies, if one with origins in the early twentieth century diving bell. For Rush’s small pod-like vessel several feet in diameter was fitted out as if inversely to a stratospheric balloon, promising take one to depths at which no humans had traveled, as if to a new frontier of utter darkness, removed from terrestrial light. But the hubris of visiting the technological disaster of the Titanic–a primal scene of the mid-twentieth century, which Rush now promoted as a disaster tourism with more than a bit of Jules Verne in it, to the confines of the known, equipped, with the self-assurance that spurred his confidence to try to push limits. Rush had assured his coworkers and subordinates that he would undergo a safety assessment of the craft–he was aboard it, after all, and claimed in board meetings about safety concerns had proclaimed “I have no desire to die,” arguing the deeps dive was “one of the safest things I will ever do,” that suggests a deep self-deception terrific in its determination to escape outside oversight. As much as the name of the Titanic promised to face the “titanic features of the wild” in the manner of the American naturalist Thoreau argued met our “needs to witness our own limits transgressed,” every schoolboy’s dream, and Rush seemed so convinced “I understand this kind of risk.” Yet although the vessel he piloted had made the trip down to the deep-sea ruins some thirteen times before, the degraded state of the hull caused it to implode suddenly at 3,000 feet depth suggested “sustained efforts to misrepresent the Titan as indestructible” animated Rush, driven not only to explore the deep sea ruins, but resist registering the craft to any nation to erase regulatory oversight: the dive in international waters evaded all governmental oversight, suggesting the fault lay not only in a “bad actor” possessed by delusions, but abilities to elude government agencies in a hot market for deep-sea exploration.

Indeed, the picture provided by a whistleblower who was far more trained in underseas missions suggest that the degraded nature of the hull that was not only exposed to deepsea pressures, but to face the winter conditions that could have compromised the composite hull, was prominent tin the number of safety concerns many felt in the submersible community, but which Rush tried to shirk off. While not diabolic or nefarious, a desire to achieve not only the insurmountable dangers of deep-sea exploration, or to “touch death” by visiting the deepsea ruins of the Titanic at first hand were animating Rush’s apparent obliviousness to oversight, and intense silencing of executives and employees to raise concern about the absence of inspectors but insistence to dive to unprecedented depths for financial gain led Rush to silence the experts that he employed, and retain the “experts” h needed for window-dressing to add public luster (rather than real oversight) to the mission.

Over the four days of panic that rescue forces and underseas divers searched to map traces or survivors of the imploded submersible, hoping that the children at least might be living, somehow, trapped in safety compartments beneath the sea, as we wondered how legal parameters on deepsea travel were avoided, we rarely heard from or about whistle-blowers who had long raised questions bout Musk’s overeager plans, trying to alert the very workplace safety regulators–OSHA; –that Donald Trump is, with eager encouragement from the business world–trying to limit and erode. For OceanGate’s quite sturdy Director of Marine Operations, sea-going Glaswegian David Lochbridge, who had worked with a range of submersibles for the Royal Navy and then as a pilot of submersibles in the North Sea, was shut out of the launch of the Titan: he was indeed silenced, and forced to watch the arrival of the titanium caps on the ends of the lost submersible as they returned to shore with everyone else. or if Lochbridge had promptly alerted to the design dangers of the tiny submersible oddly named the Titan,-as if it were the lesser cousin destined to meet the Titanic. The underseas engineer wrote promptly to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration–OSHA–in the United States, who themselves had alerted the U.S. Coast Guard. Yet OceanGate lawyers were set like attack dogs: they insisted that he pay $10,000 for compromising their project, and asked he drop his complaint immediately, charging theft of intellectual property. It got only worse: “From the initial design, to the build, to the operations, people were told a lie,” the expert pilot ruefully remembered. The charge of a theft of Intellectual Property that OceanGate was ready to lodge was, of course, entirely bogus–the IP was nonexistent, as the submersible was not able to endure such high pressure, and the problem was poor engineering rather than theft of trade secrets.

The carbon fibre hull built by the University of Washington Applied Physics from 2019, however for a hull designed for constructing “the shallow-water vessel” called Cyclops 1, made from different entirely materials–steel instead of the carbon fiber as was the case of the hull of the Titan–for diving 500 meters or 1,640 feet, not the 12,500 feet the Titanic lay (“APL-UW expertise involved only shallow water implementation, [and] the Laboratory was not involved in the design, engineering or testing of the TITAN submersible used in the RMS TITANIC expedition,” wrote the executive director of the UW Applied Physics Laboratory in a June 20, 2023 to distance himself from the OceanGate disaster into which he feared his laboratory was implicated, claiming it only offered its services for “shallow water implementation.” Yet Rush was explicit in noting that the college’s broad background in ocean engineering to develop “fixed and mobile ocean systems” for “deep ocean exploration” was always OceanGate’s final goal, and the laboratory claimed experience conducting research on the deep ocean floor that no doubt attracted Rush in the first place, as he sought help for OceanGate to build a submersible that in “the development, construction, launch, recovery, test and analysis of a deep-ocean, manned under-water vehicle.” Rather than rooted in trade secrets that defined the enterprise of deepsea exploration, the carbon fiber hull, designed as if it were indeed a voyage to another planet and inexperienced space, recalls the Carl Sagan image sent to outer space for extraterrestrials, more than the ability to withstand tons of pressure, and multiple flaws in its assembly to withstand the pressures most engineers would quickly realize.

The confidence game that Rush was able to While David Lochbridge and his wife called OSHA every few weeks to alert them to the cracks, pops, and delimitation of the carbon-fibre hull that had been specially built for the submersible’s descent and the glue that bonded it to the titanium rings, by December 2018, Oceangate legal team demanded Lochbridge and his wife drop their complaints and the observations they offered on the plans for descending in the submersible. The legal team successfully delayed investigation of the craft that had never been certified by any third-party organization, as Lloyd’s Register or the American Bureau of Shipping, but was allowed to descend in international waters: the lawyers deflected any investigation by OSHA by charging Lochbridge with appropriating trade secrets, fraud, and theft; he had sought in vain the whistleblower protections from OSHA that never arrived-even as experts at the Marine Technology Society joined the DMO in raising safety concerns about the safety standards for the titanium hubs, evading the industry standards in March, 2018, ways likely to set back the entire industry of underseas exploration by “negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that would have serious consequences for everyone in the industry.” While the cute submersible was promoted as able to navigate safely in any aquatic environment–but little intellectual property or “trade secrets” worthy of the name.

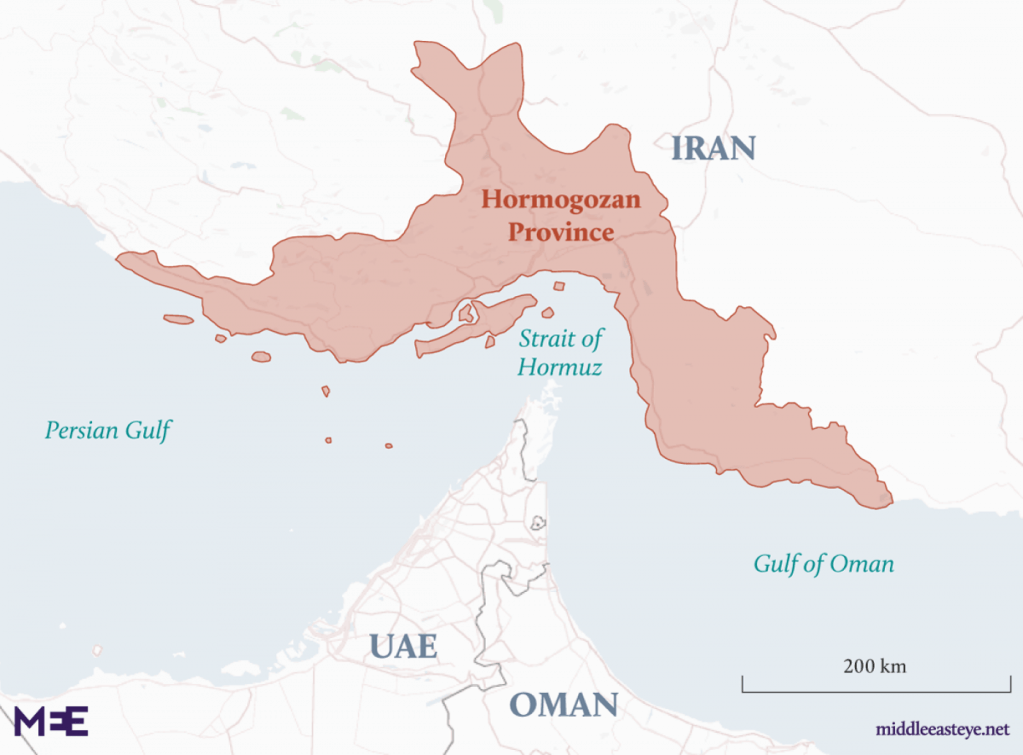

The questions that had been raised about its joins of tail cone or porthole and the degradation of the lamination of the carbon-fibre material, not used in arctic conditions, in winter weather of the waters off Newfoundland evaded the regulatory frameworks in place for national or international rates. Did Rush realize that the lack of oversight in international waters off of Newfoundland where the Titanic had previously sunk allowed the escape hatch he needed to press full speed ahead with plans that many doubted would be able to sustain deep-ocean pressures, let alone those on the ocean floor? The Titan, of course, never reached that ocean floor destination, as it had advertised.

Experts Worried the Laminated Carbon Fiber Hull would not Withstand Pressures on Ocean Floor

This was not under the radar. Ocean Governance was evaded as Rush was working without any oversight to fabricate a submersible he claimed was able to withstand underseas pressure based on his own engineering training alone, and his zeal to conduct underseas missions at the ocean floor. By insulating himself with pseudo-experts–from Pierre Nageolet, working outside of deepsea protocols in place for some time in engineering communities, and silencing his whistblower by intimidatory tactics of actual or threatened lawsuits, who he quickly sacked without grounds, And while the U.S. Coast Guard has determined that the almost instantaneous explosion of The Titan, the submersible Rush helped design and whose construction he single-handedly supervised and oversaw resulted from a failure in the glue joining the hull and titanium ring, or the carbon fiber hull’s delimitation as a result of wintering in the north seas, the simulation of how the submersible en route to carry passengers to the ruins of the HMS Titanic after an hour and forty-five minutes may have been a “painless death,” the four days of panic as to its fate conceal the deep dangers of lack of safety oversight or regulations in an almost unregulated search for underseas minerals that seems to have driven Rush’s rather single-minded pursuit of a way to explore underwater canyons on the ocean floor and deepsea territories long hidden to the human observer.

The exploration of the underseas, as much as following Jules Verne’s nineteenth century adventure books, was driven by a growing market for mineral and energy speculation as much as personal glory. If the truly catastrophic implosion of the submersible lasted but milliseconds–too quick of the mind to process, per YouTube sensation Dr. Chris Rayner, who has most recently piggybacked on the global catastrophe, asserts. If the hull collapse may have been preceded by squeaks and pops that inspired panic, the possible site of collapse and structural failure—the viewport, the adhesive seal between the titanium end-caps and the collapse of the cylindrical hull–resulted from evading oversight of nautical regulatory bodies, perhaps steeped in the ethos of American individualism, but driven by a market for offering new platforms of first-hand underseas oil exploration to oil companies and engineers in search of deep sea minerals–the very community of engineers Rush hoped to win over for the benefits of the submersible as a mode of underseas mapping. The need to evade the law of the seas, and situate the site of exploration in international waters, was situated at the ruins of the Titanic to attract worldwide media attention, and pull other outsiders into Rush’s outsider project, evading any regulatory commissions or guidelines on passenger safety. All of Rush’s passengers had of course signed release forms prior to boarding the Titan, and the pressures to which it was exposed that reached 5,000 pounds of pressure per square inch. Carbon fibre was an “unpredictable material” all along for such depths of 3,000 feet, if not an impractical one, raising questions of why Rush was so committed to allowing multiple untested features to remain before performing the dive, advertising the ride to passengers he would take to their deaths as entirely safe.

1. The romance of the underseas exploration was clearly intensified–and made attractive to financial backers–by the nature of its destination: the ruins of the Titanic–and, however paradoxically, the ability to transcend death. The expression of a desire to transcend perceived boundaries was communicated to Stockton Rush as a boy in Walden, or Maine Woods, where Thoreau waxed ecstatic at an almost mythic awareness of something “vast, Titanic, such as man never inhabits”–channeled by the original transatlantic transatlantic voyage that mirrored the telegraph to the Newfoundland coast, before hitting an iceberg, to the search of the steel ruins still lying submerged undersea. Rush sought to break new boundaries of the globalized world by the venture of OceanGate, as if breaching new frontier of exploration, if not an affirmation of personal vitality and renewal by traveling to a space “such as man never inhabits,” where “inhuman Nature has got him alone.” It is impossible to read the ecstatic revery of how Nature moves man and “pilfers him of some of his divine faculty” as an open invitation to descend into the deep of the ruins of the Titanic, to relive the massive tragedy of the first decades of the twentieth century, as attempting to reconquer time.)

Stockton Rush had recuperated a narrative of canasta with deep roots, if one that was promoted in the recent films that had become museum shows and even adventure rids at amusement parks–but this, as if in contrast to studio recreations, was promised as the utmost exhilaration of the real thing. But was it ever reality, so entangled was Rush’s promise with beliefs in transcendence that trained generations of readers of Thoreau to search for sites of transcendence beyond our abilities? Or is the fiction of transcendence that Rush promised to paying customers, and that Thoreau had so memorably inspired, gained new meanings in a world defined by globalization, where the voyage of Stockton Rush into the depth of international waters, outside legal oversight, been tainted by the map of globalization, and indeed inspired by the abilities to transcend our own known limits were newly conflated with the transcendence of legal regimes, and indeed the transcendence of limits of deepwater exploration for energy reserves that oil and gas multinationals hoped to extract from the deep seas, but lacked the requisite technology to survey? For the voyage in the modern diving bell was indeed a trial balloon to industries eager for tools of underseas mapping promising greater precision, that it isn’t unlikely to think Ocean’s Gate was eager to market, for far more money than offering exerting underseas joy rides of disaster tourism. And a very different if related sense of “Titanic’ that Thoreau used in Maine Woods, of something that “was vast, Titanic, and such as man never inhabits” where “Nature has got him at a disadvantage” might better describe the deep seas.

The bravura of descending by a diving bell had been memorably used in the mid-century novel Dr. Faustus by Thomas Mann as an aesthetic experiencetragically tainted by hubris from the start. Mann seeks to express the Faustian goals of his hero, Adrian Leverkühn by the diving bell he travels undresea to witness unknown monsters in perfect submarine darkness, far from humanity, in the diving bell that prefigure the ecstatic aspirations to symphonies he hopes to create. The trips with Dr. Capercale to the underseas world with a fictional scientist, as pushing the limits of human understanding. Leverkühn claims to have experienced new limits when he descended in the waters off Bermuda, only several sea miles from St. George, in the company of a man who claims to “have set a new record for depth” underwater. Mann’s memorable hero descended in a “bullet-shaped diving-bell” that transcended human limits, descending a if in inverse to the stratospheric balloon it resembled, promised to be “absolutely watertight, . . . capable of withstanding the immense pressures and came equipped with plenty of oxygen, a telephone, high-powered searchlights, and quartz windows for viewing on every side.” If ‘anything but comfortable” they were secure in their descent, “by the knowledge of their safety . . . beneath he surface of the ocean” behind four-hundred pound door, as descending to perfect darkness at 2,000 and then 2,500 feet, bearing 500,000 tons of pressure.

Leverkühn somewhat cozily entertained his friends with gusto of the descent to underseas depths, smoking a cigarette. The voyage was a metaphor for the modern Faustian bargain he made with the Devil, sacrificing human love for his skills of composition. For in the descent to the inhuman realm, he described having gained “glimpses afforded onto a world whose silent, alien madness was justified–and explained, so to speak–by its inherent lack of contact with our own” in the descending chamber, in three hours that “passed like a dream, thanks to the . . . glimpses into a world whose soundless, frantic foreignness was explained . . . by its [absolute and] utter lack of contact with our own:” “all around reigned perfect blackness” akin to “darkness of interstellar space.” Diving bells not only provided visits to witness sunken wrecks off Bermuda’s coast on the ocean floor, but conjured a transcendence of the human, in an unmapped region beyond the limits of the known, traveling 3600 feet below the seas surface in a two-and-a-half ton hollow ball for a half an hour, looking through quartz windows “into a blue-blackness hard to describe, . . . eternally still . . . not quite allayed by the feeling science must be allowed to press just as far forwards as the intelligence of scientists is given license to go.”

Else Bostelmann, Dragonfish or “Bathysphere Intact” off Bermuda (1934)

The images Else Bostelmann offered in scientific periodicals captured the fascination of underseas that colonized the imagination; “the incredible oddities that nature and life had managed here, these forms and physiognomies that seemed to bear scarcely any kinship with those on earth above and to belong to some other planet, . . . hidden in eternal darkness.” The deep sea hid “these abstruse creatures of the abyss” that seem “to have no tie to humanity” provided the first ken of the pleasure Leverkühn takes in flaunting familiarity “his experiences in regions monstrously above and beyond us humans,” plunging with diabolic relish and ease among the “deep-sea’s life grottesquely alien life-forms, which did not seem to belong to our planet.” His friend thinks that the indulgence of these memories seemed “a devilish prank” of “the horridities of creation” able spur him to a new form of composition of the “cosmic music, with which he had become preoccupied,” before World War I, in compositions the narrator condemns as a “sardonic lampoon apparently aimed not only at the dreadful clockwork of the universe, but also at the medium in which it is painted . . . at music” of “a nearly thirty-minute orchestral portrait of the world is mockery–a mockery that confirms only too well the opinion I expressed in our conversation that the pursuit of what is immeasurably beyond man can provide no piety or nourishment.”

The sense of an infernal voyage was amplified in the disaster on the way to visit the Titanic’s ruins. For that voyage was akin to the blasphemic nature of what Mann’s narrator calls a” Luciferian travesty” and blasphemy against the elevated medium of music expressed–or mapped?–by artistic ambitions to transcend the human world. For Mann, writing in global war during the 1940s, the desire of Leverkühn seems one of technology and modernity that might be captured by Adorno, whose music criticism he had pillaged in the novel–deeply human problems of alienation that plagued the mid-twentieth century and Nazi period. These musical compositions, after all, confirm Leverkühn’s own diabolic pact, only hinted at or foreshadowed in the book’s earlier chapters. The imagined underseas voyage was a voyage to the unknown depths of the ocean provides the basis for describing his imagined trips to outer space; the orchestral fantasia suggest horror in the ears of his admiring friend, for a Godless vision to dethrone all religious humanism of a search for music able to describe the terrible marvels of outer-space or grotesqueries of the deep.

The Faustian nature of Stockton Rush’s quest was nothing if not a Faust-like underbelly of globalization, this post argues, piggy-backing on Mann’s shoulders for a bit, from the perspective of globalization and deregulation that open up the deep with even more terror. While Mann will be less a focus of the post, I will follow him in examining and descending into the terror opening up of ideas and imaginations of prospecting the ocean’s floor multinational firms of opened by hopes of prospecting. For the huge bonanzas of extraction have opened up new deepwater spaces, as access to the deepwater reserves of energy or rare metals provide secret promises to an eternal ability of extraction, a search for energy sources that is a broader Faustian problem by Big Oil we can only see, but is almost engraved in the desperation on his face as he readies to plunge to the ocean floor.

The Faustian nature of the deepwater voyage within the curved steel walls of a cast iron Bathysphere had been devised to protect the biologist William Bebe and his assistant from the dark, boasted to guarantee against the heightened pressures of ocean depths few had experienced or would survive. The thrill of the deep seas plunge that exposed the vessel to such enormous atmospheric pressure left in the composer the sense of risk in his skin–a “prickly sensation that came with realizing one was exposing to sight what had never been seen, was not to be seen, and had never expected to be seen” whose unavoidable “sense of indiscretion, indeed of sinfulness, could not be fully mitigated and neutralized [even] by the exhilaration of science.” Ocean scientist and engineer Bebe gained nearly global attention for his exploration of deep ocean life behind two fused eight-inch quartz portholes in 1934,–a new horizon on uninhabited worlds electric light was able to reveal to human sight as a technological wonder of observation, a new sort of scope regime. The biologist reported observations be telephone to a nearby boat–for Mann, a bestiary of “mad grotesqueries, organic nature’s secret faces: predatory mouths, shameless teeth, telescopic eyes; paper nautiluses, hatchetfish with goggles aimed upward, heteropods and sea butterflies up to six feet long.” The descriptive relish of revealing this hidden bestiary cannot capture the strangeness Else Bostelmann imagined for National Geographic of the deep sea life illuminated in the Bathysphere she never participated. But thirty-five pioneering dives were conducted, many years after the Titanic sunk in the far colder waters off Newfoundland, its starboard air chambers shattered as they hit an iceberg.

The transport Adrian Leverkühn imagined might be conveyed in Bebe’s ambitions to view “here, under a pressure which, if loosened, would make amorphous tissue of a human being . . . here I was privileged to sit and crystallize something useful.” The sturdy Bathysphere set records descending to 1,200 feet; diving spheres soon plunged to 4,500 ft., if only a third of the way to the 12, 500 feet at which the Titanic had sunk. The deepwater voyages became the subject of a popular film by 1938,–perhaps as popular as the recent blockbuster of Titanic’s sinking–and a spectacle of the revelation of the uncanny creatures of the Deep Sea, capturing the excessive hope that in part animated Stockton Rush in his own fantasia–if it didn’t hint that he wasn’t driven only by science or exploration, but monetary profit, revealing the huge financial benefits of surveying the underseas world in an age of globalization that threatens to expose more and more underseas minerals to hopes of extraction, in a Faustian bargain we have not yet come to contemplate fully but is increasingly waged in maps, and cartographic precision to map sites of extraction underseas.

The absolute alien nature of the darkest reaches of undersea life must have epitomized the Faustian bargain of Leverkühn, eager to court danger of the inhumane for renown. Thomas Mann was in fact describing the underseas as an inevitable attraction for the composer who made a deal with Satan in Dr. Faustus (1946), one imagines akin to the compulsive attraction with which Stockton Rush persued th e deep. The plunge below 4,000 feet was sufficient other-worldly to recall a pact with the devil, as the idea of descending and returning to the underseas graveyard of the Titanic’s ruins.

Yet the attempt to market underseas heroism of tempting fate that Stockton Rush offered the passengers of the submersible he called ‘Titan’ never did reveal “what genuine underseas exploration looks like;” its passengers all met with death. Mann described the eery inhumanity of a descent below 2,400 and 2,500 feet, opening “an interstellar space unvisited for eternities by even the weakest ray of sun,” to be “examined under a brutal artificial beam, . . . brought down from the world above” as a bridging of life and death. Rush’s unwarranted promise of survival in such a transit to the deepsea ruins is however akin to how Leverkühn courting exhilaration before “forms and physiognomies that seemed to bear scarcely any kinship with those on the earth above and to belong to some other planet,” unveiling not “products of concealment . . . hidden in eternal darkness” compared only to “the arrival of a human space-craft on Mars.” But what Rush promised was underwritten and sponsored by a deeper diabolic pact of hoping to sell the submersible to multinationals after its media success for use prospecting oil and precious metals below the sea we are unable to map.

Continue reading