It hardly is a coincidence that the narratives of many disaster films parallel less of a storyline than what might be described as an imploding map: the destruction of familiar landmarks, the upending of orientational signs on a map, and unsettling of the known world extend far beyond the erasure of whole cities, whether New York or Los Angeles, from the map–or even an existential sense that we are the sole survivors, stranded on the surface of an unmarked map. Such filmic narratives mirror a sense of deep anxiety about the coherence and reliability of the map, or of how maps might help us to navigate space and to process a cohesive or coherent record of terrestrial expanse. When one enters cinematic space, there is the horror, which we can barely stop watching, of having that sense of space implode, as the familiar landscape which we’ve been accustomed to orient ourselves within is suddenly open to threats of inevitable destruction.

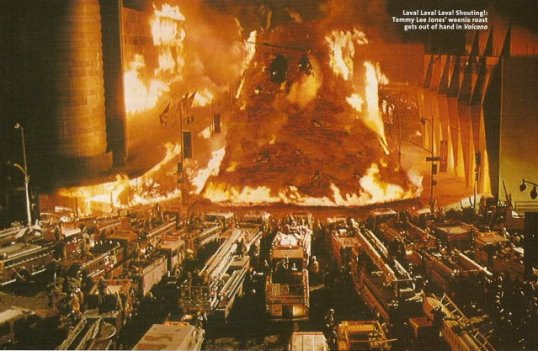

Cultural critic Mike Davis has excavated a history of filmic adaptations of the destruction of Los Angeles, pointing to the multiple fictive destructions of the city of angels by tornadoes, storms, earthquakes, fires, sea monsters, snakes, wolves, or wild bees as a projection and a response to the fragile ecology of the city itself–as if the screen images of natural destruction were the return of a repressed awareness of the region’s ecology of So Cal, and particularly of the basin from the San Andreas Fault and San Gabriel mountains to the Pacific. Of course, Los Angeles has been defined so many times since the 1950s in film, it is difficult not to lapse into chronicling the appearance of such cinematic destructions, if not evident restlessness on the part of screenwriters to move from the 1974 “Earthquake” to volcanoes, viruses or tidal waves–as in the film “Volcano” (1997), when a volcanic eruption threatens to destroy the entire city and its inhabitants.

Davis made a strong case that the fairly self-referential act of destroying what was the epicenter of movie-making in the United States was not about the medium of film, but the denial of the quite precarious environmental volatility in the city itself. “Earthquakes and fires and floods are just the normal metabolism of the landscape,” Davis remarked in an interview; “but we deliberately, almost, keep putting ourselves in harm’s way,” or court disaster in order to deny it. Take the building and rebuilding of mansions at the mouth of canyons out of which the Santa Ana winds carry fire every decade or two. He observed that at the same time natural disasters in Southern California were minimized in much of the early part of the century in the press, there was an odd normalization of the destruction of LA in particular in a slew of films that detract attention from the political ecology of the region in the name of entertainment.

In a somewhat early modern way, the city of Los Angeles became a microcosm on which to project world disaster (or the disasters of modernity) that repeatedly recurred in a string of bloated disaster films of the 1970s and 1980s, from “Earthquake” (1974) and “The Towering Inferno” (1974) to “The Swarm,” that dangerously threatened white men.

The relations between the destruction of Los Angeles that repeatedly occurred on film had clear grounds to be confused with the fires that ravaged its nearby hills–especially for the inhabitants of the city itself. The recent 1990 Station Fire arson provoked an interested comparison to the mushroom cloud that would be created by the tonnage of a Hydrogen Bomb. “Was it Hollywood that provoked the Station Fire, as a means to assert that life must follow its ‘art’?” asked one blogger wrote.

To be sure, the fire created both a filmic image of destruction, and exploded the calm coherence of a map of the region:

News outlets took some pleasure in the perverse congruence of Hollywood representatives and those charge of response, as Arnold Schwarzenegger himself traced the fire’s effects on a state map as if to contain the disaster that unfolded on TV:

Davis was not only concerned with film-sets, of course.

Davis showed how the rise of apocalypses that engulfed LA paralleled a deep historical denial of the ecological destruction perpetuated by the encasing of rivers in concrete and destruction of open spaces revealed in the 1930 Olmsted-Bartholomew Report, “Parks, Playgrounds and Beaches.” This report, which detailed the effects of rampant urban expansion–and in the 1990s became an icon and emblem for the destruction of LA’s natural environment, and a “lost Eden” irrigated by riverine paths was transformed into a transformation of the Los Angeles river into a freeway–had the odd distinction of being suppressed by the very Chamber of Commerce that had commissioned it to be drawn, so clearly did it represent an image of the city that they city did not want to encourage.

Something similar is at work in the disorientation created by the implosion of familiar sites and landmarks–and mental maps–in films that localize destruction or map apocalypse for the masses at the multiplex. Whereas Davis provides an image of a city that relentlessly throws itself into harms way with oblivious denial and a slight shrug, there is a pleasure in watching the familiar destruction of the map compensates for our own fears of disorientation in striking ways.

This is the destruction of a local network, or a lived network, as if to assert the authority with a fatal stroke of an imaginary world that engulfs the viewer in its violence. The effects are uncanny. The juxtaposition of “news” and filmic narratives of destruction in the post-9/11 world has been widely noted, as have the precursors of the tragic suicide attacks that killed so many on studio lots and in the megaplex. The parallel between images of destruction and of the towers’ collapse is chilling–as the common difficulty many had in discriminating the destruction in New York City (and elsewhere) from the familiar images of a disaster film.

The rising threshold of shock value of scenes of mega-destruction in many films of the 1990s both contrasted with the relatively quiescent era of the Clinton years, and made it oddly difficult to distinguish fantasies of urban destruction from actual destructive events. There is a broader sense of disorientation to which the recurrent implosion of familiar maps on the multiplex screen reveals–as well as a deflection of anxiety about something as potentially tragic as a terrorist attack. The implosion of the maps is worth contemplating in recent films, because it creates something of a parallel universe on screen that oddly offers a promise of orientation on a level of fantasy in its repetition of a global or a micro-apocalypse. There’s a fairly big prehistory, of course, for the destruction of iconic place-markers, from:

to Los Angeles besieged in war:

The implosion of the coherence of place in these pictures suggests the attraction of watching a literal implosion of the known map in both films shortly before the disastrously fatal airplane attacks of 9/11. And since then, Hollywood seems to have responded by treating the screen as a sort of imploding map of the world on truly phantasmagoric proportions and scale, as the urban canyons created by the iconic Empire State becomes a site of Amazonian appearance, blending nature and culture and undermining our maps:

There’s a familiar melancholia in Nicolas Cage’s wistfully longing eyes that once more brim with stoic regret. He might be recalling an era of films with more coherent narratives, or a more ground-bound perspective on human events that he seems resignened to accept as a thing of the past.