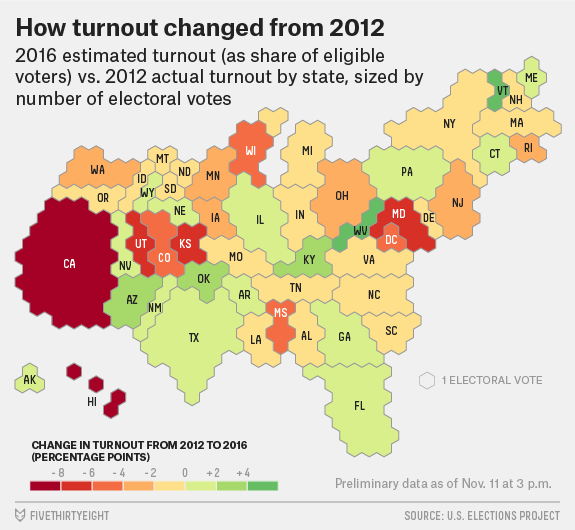

It seems, goes the popular wisdom, Donald Trump stunned the country by being able to make up for the lack of a party organization by followers he developed on Twitter. But Trump was able to tilt against a candidate he was able to identify with an establishment, and an establishment that he convinced voters had not served a plurality of states, as a salesman of something different than the status quo, adopting a highly mediated populism that was rooted din claims to reorganize the state and its effectiveness. The bizarre combination of an outsider who promised a range of constituencies that the state would be remade in their own interests–defending American sovereignty; returning jobs to depressed regions; defending anti-immigrant interests–may not be able to be aligned directly with the appeal of a fascist state, but provided a collective identity for many that gave meaning their votes, at the same time as dropping voter turnout across the midwest and new restrictive voting laws, including in Wisconsin and Ohio.

Trump gave a greater sense of urgency to the crucial number of undecided in his favor–before a broadly declining turnout nationwide, but also decreased turnout in many states where differences in the popular votes were small, as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa, and pronouncedly higher in the “deep south,” based on estimates of the U.S. Elections Project.

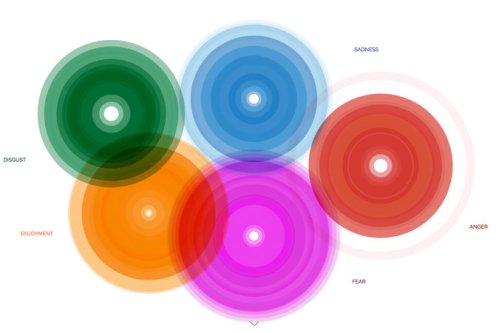

The extraordinary effectiveness of Donald Trump’s affective appeal to voters in the 2016 Presidential remains particularly difficult to stomach for many, moving outside of a party or any civic institutions, but rooted in the adroitness by which he branded himself as a political alternative. Trump’s uncensored comportment was central to the success of that campaign, many have noted, as it lent cathartic license for exposing emotions of fear, hatred, and anger rarely seen in political discourse–and seemed to run against reasoned discourse. The performative orchestration of a wide range of emotions–tilted toward the red end of the spectrum market by fear; resentment; indignation; anger; disorientation–which drew lopsidedly from an atlas of emotions. If the range of emotional responses were triggered in a sense by the prominence of social media, which allowed a quite careful orchestration of retweeting and public statements designed to trigger emotions to make political decisions, it was orchestrated carefully more from Reality TV than Reality,–orchestrating its audience’s attention by means of quite skillful editorial manipulations of footage, fast cuts, and clever stagecraft to create the needed coherent story from declarations, angry accusations, and assertions. Trump’s campaign touched on issues of fear and anger, hopping between nearby sectors of the below map, but focussing attention on a fear of women and scapegoating of others to manufacture an actually illusory model of strength.

The emotional integrity was more important than the language–leading to bizarre debates as to whether his supporters took him literally, or if his references were serious in content even if the actual utterances he made were not in fact as central his appeal as the feelings of antagonism and alienation that he so successfully seemed to tap.

As a creature of the airwaves, Trump used emotions as a way to orient voters to the changing world of globalization by emotional venting that appeared to defend a past order: despite his lack of qualifications to serve as President of the United States, the defensiveness created a source of validation for his candidacy that few expected, but are so familiar to be available to install as browser extensions via Reaction Packs. The recognition of Trump’s display of emotions are so familiar that they convert easily to downloadable Reactions as emoji, so iconic has been Trump’s animated orchestration of anger, fear, and resentment across the body politic, in ways that remain difficult to map.

The popularity of such “rage faces” recouped the repeated registering of emotions in Trump’s campaign. Indeed, Trump’s–or the Trump campaign’s–active retweeting of 140-character declarations defaming individuals or amping up socio-economic antagonisms prepared the way for the recognition of these emoticons which, although not released or sanctioned by Facebook, had first become recognizable in American political discourse that summer in much of the American subconscious.

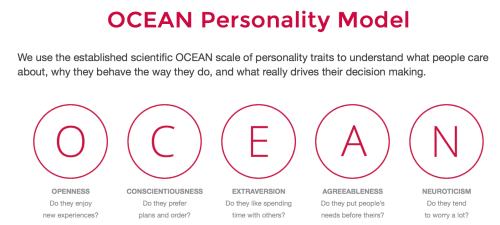

The animated reactions engaged many online not politically active or voted in previous elections, redefining the political landscape outside of red versus blue states, and mirroring tools of psychometric profiling–first successfully used in political settings to mobilize support online for “Leave E.U.” in the Brexit campaign–first framed by researchers at Cambridge Analytica, developed by an psychologist Aleksandr Kogan, before changed his name to Dr. Spectre, sold to the MyPersonality tools of Cambridge University’s Psychometrics Centre to the shady Strategic Communications Laboratories, who in 2013 established Cambridge Analytica in the United States. The tools had indeed boasted the ability to measure voters’ personality from their digital footprints, decrypting psychological criteria for emotional stability, extraversion, political sympathies, able to predict sexual orientation, skin-color, and political affiliations by using FB likes as an open-source psychological questionnaire based on an OCEAN scaling of personality traits that rank the positive-sounding values of Openness, Conscientiousness, Aggreeableness, and Neuroticism, all the better “to understand [their] unique personality type” in order better to define their decision-making process–each letter can be clicked to reveal a face registering individual emotions on their website, in ways that creepily echo emoticons as tools to achieve “better audience targeting” by “better audience modeling” through 5,000 data points per individual.

Through such data profiles and the pseudo-scientific claims of “audience insight” or “targeting”, Trump was helped to orchestrate emotions to construct a sense of belonging.

For despite his lack of political qualifications, if in part because of it, Trump represents the victory of the unqualified–“the people”–and an illustration that someone outside of a political system can assert their importance in government, and to discredit the political system itself. While Trump’s campaign had not been data-heavy, the use by Democratic strategists of big data analysts from BlueLabs had perhaps encouraged the Trump campaign to turn to Cambridge Analytica, whose boasts of a huge ROI for political campaigns would be wildly boosted by the June success of “Leave” in the Brexit vote. The orchestration of emotions most familiar from the production values of Reality TV have little precedent in politics, but was honed against those assumed to be part of a political class and designed to refute any notion of scientific expertise.

The particular targeting of emotions of dislike, fear, and resentment increased in the Trump campaign from mid-August 2016, about a month after the marquee event of the Democratic convention celebrated diversity, with the entrance of Stephen K. Bannon, serial wife-abuser of Breitbart fame, and he who invoked the “church militant” to explain the need to bind together church and state in fighting for the beliefs of the West as campaign chief of the Trump campaign, united a deep fear of refugees, terrorism, and “Radical Islam.” The accentuation of such a call to militancy was tied to an accentuation of misogyny in the Trump campaign, as Bannon joined Trump’s new campaign manager pollster Kellyanne Conway,to play to the lowest common denominator of voters through their economic and social fears, in ways that particularly distorted the campaign that benefited Trump and tilted to the unique brand of misogyny. In ways that shifted the logic of the campaign for U.S. President after both conventions had concluded, the expansion of Team Trump helped direct a model of behavioral sciences–already used by NATO in Eastern and Central Europe as propaganda against the dis-information released by the Russian government–as a rallying cry uniting many ranges of hatred–the “deplorables” Hillary Clinton famously and perhaps fatally invoked–within the highly charged emotional language of Trump’s campaign.

Many refused to label Trump as recognizably fascist in his political thought, despite his outright xenophobia, manipulation of fear, and cultivation of a rhetoric of crisis, refusing to recognize the roots of his strong authoritarian characteristics by a name that has long been identified with utmost evil, in an attempt to explain Trump as something else. Most notably, historian Robert O. Paxton allowed that Trump only openly took a selective rehabilitation of the anti-modern fascist movements, whose strongly authoritarian character offered “echoes of fascism,” rehabilitating the sanctioning of social violence, suspension of rights, and dehumanization from fascist movements in his assertion of openly extra-judicial rights he asserts as a leader. Yet in its open aggression motivated by a the violence of urgency–and in its turning in from the increasingly complex world that Obama attempted to navigate, and rejection of globalism, as in its rejection of civility and disdain for women, Trumpism closely rehabilitates fascism in its doctrine of prerogatives of the protection of the state that transcend constitutional law, or the subordination of constitutional law to Staatsrecht. Whereas fascism arose in response to international communism, Trumpism seems an open response to globalism of the twenty-first century.

While not a direct descendent of fascism, Trump has defined himself as a man of action–together with Bannon–in his proliferation of executive orders as a form of decisions, creating the relation of individual to state in his own oratory and the security of America that he claimed to guarantee. The championing over urgency and privileging of emotions and accusations over issues–a hallmark of fascist politics–serves to fabricate public consensus, cast in Trump’s tacitly gendered assertion “America needs a CEO,” as if to call into question the existence of a historical authority in the state. While Paxton rightly lamented increased usage of “fascist” as an accusatory epithet, able to be applied interchangeably to the intolerant authority of the Tea Party, the intolerance of the Islamic State, or Donald Trump, but failing to discriminate its actual target, Trump’s near-consent courting of the limits of Freedom Speech led him to launch attacks that test the limits of Free Speech and First Amendment, shocking many neighboring countries,– “I’m so tired of this politically correct crap”–labelling political correctness as “the big problem in this country” to which he claims his own authority will create a long-awaited corrective.

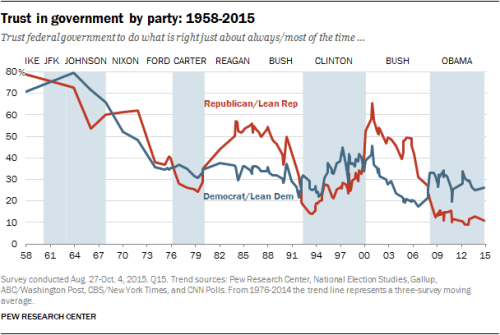

His campaign, notwithstanding serial unrepentant falsehoods, his campaign promised to rectify confusion by the ability to Make America Great Again, invoking an idealized notion of country to which he invited all to rally behind and stigmatizing the most vulnerable scapegoats–the undocumented; the refugee; the poor–as targets of collective anger, albeit without racialized theorization of a subordinate status or staking openly ethnic claims. Trump sewed a steep set of divisions in the nation that were concentrated in non-urban areas in “swing states,” but which corresponded to the emotional aesthetics of and a deep feeling of abandonment–a deeply declining distrust of government across the nation not adequately mapped a full year before the election, far deeper among Republicans than Democrats but at record low–but supported by a broadly declining belief in government fairness, across “red” and “blue” states.

In many ways, the vote was the victory of a performative model and the emotional satisfaction that that model of performance offered. Trump’s victory made sense to those who bought the promise of those who believed that America Needed To Be Made Great Again–and who entertained the importance of time-travel to do so, and entertained a delusion of going backwards in time. For Trump appealed precisely to those areas and regions that entertained return to a past, conceived of often as a rebirth of a lost economy, peacefulness, and prosperity, but concealing an era of small government, and proposing the myth that there was indeed a chance of returning to a bygone of the imagination: many saw a rejection of globalism and of multiculturalism or of a disturbance of a past gender politics, and they saw it as best embodied in someone himself moored in an earlier, whiter era,–and a civil society in which charges of Trump’s gender could not be made to stick. Trump’s performative model seemingly surpassed logical contradictions inherent in his words or person, making it all the more difficult to comprehend, even as we have repeatedly turned to maps to do so–even as we were frustrated by them: Trump’s wealth papered over the huge contradictions of someone whose wealth was apparent, as he performed the role os a man of the people; his age was apparent, even if his improbably marriage to a younger woman could conjure an image of apparent potency; his lack of political convictions was concealed in a patriotism that few saw the need to question; his lack of political expertise affirmed the lack of relevance of expertise to getting the job done, as it only confirmed a belief in the failures failures of a political class and distrust of government already at historic lows across the country.

The Stuff of Poetry. Congrats again. Will their be an addendum headed: Trump Stigmatizes Cruz?

Pingback: Mapping the New Isolationism: America First? | Musings on Maps