Is the notion of the offshore trumping national sovereignty as a means of storing and generating wealth? As much as the phenomenon of globalization is a mutation of the nation of clear bounds, or clearly mapped bounds, the discovery of the offshore has been as central to the economy of the globalized world as the discovery of, say, the Indies or America was once central to Mercantilism. For the offshore is often considered a negative space, apart from the world of nation, apart from settled lands, apart from industrialization, or post-industrialization, the offshore plays an increasingly commanding role in the global economy to sequester funds and finance. And if the offshore was invented by legal conveyance as a way to avoid taxation of sovereign states, it is increasingly corrosive of the state, and as much as a legal fiction demands to be understood as a “discovery” internalized by a new financial class, and global elite, as a new operating strategy in the global economy. If even the realtor turned oligarch turned autocrat Donald Trump is a product of the offshore, this is a new playing board for the game of global competition, giving financial elites an upper hand, but demands to be traced as a discovery that will have deeply corrosive effects of international landscapes and a national good. For why need government exist, if most funds are stored offshore, and why does taxation or any financial administration of currency need to exist, if increasing funds are docked on offshore reserves?

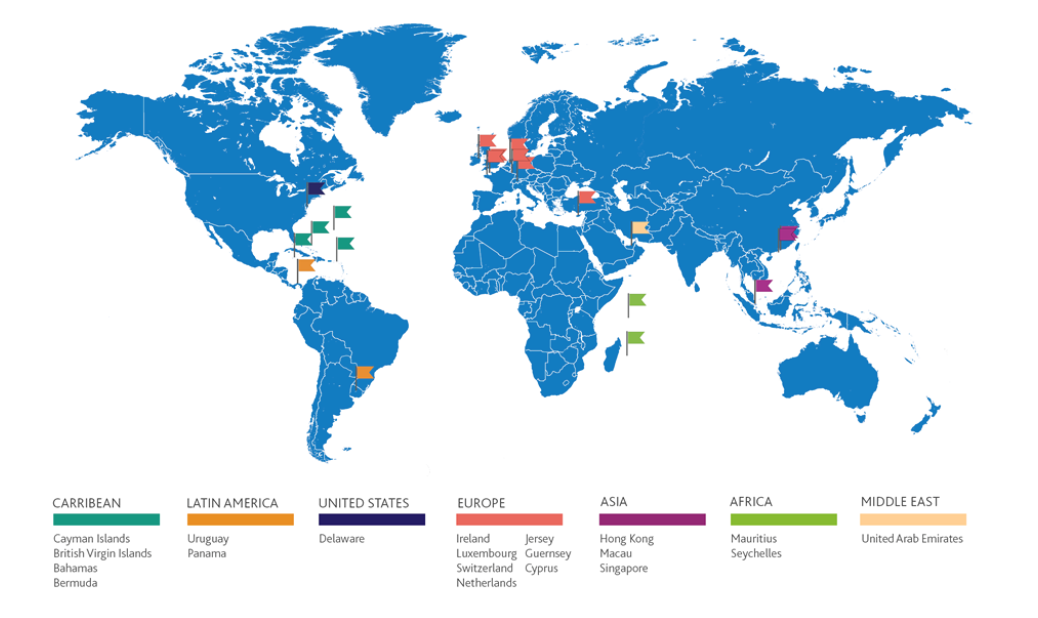

The notion of the “offshore” suggests a realm out of reach of the law of the land, existing just off the coast of the regions supervised by regulators and taxmen, but has wildly expanded with the perpetuation of the legal fictions of the offshore as a place that offers an escape from national programs of taxation. Rather than exist only as a region beyond the shoreline or coast, and lie of the known map, the “offshore” is what escapes legal overview–and lies outside of national legal bounds. Arising as a convention to designate “offshore spaces” that lay outside of the recognized sovereign tax codes. But “offshore” regions need not properly be removed far from the mainland, or even from it at all–and are found on most any region or continent, save Antarctica. They are places where money of the superwealthy is invisibly routed, out of sight, not to remain, but to escape regulators’ oversight or the payment of a national tax or subject to national sovereign claims. The map of the offshore is increasingly a map of the unseen paths of where the superwealthy’s funds go. We are supposed to park our funds offshore to avoid taxes,

The growth of the offshore is not a place to locate money, indeed, but through which circuits of international capital travel in a globalized world. For the expansion of the offshore is a not so odd consequence of globalism, and the increasing fluidity of finance to travel smoothly across territorial bounds–an ability to sequester funds just out of site, nestled in offshore accounts that are not subject to state scrutiny or traceable by paper trails. We have recuperate the notion of islands, removed from the shore, as a new way to symbolize and achieve the escape from regulation: the offshore as an entity emerged with the ability to dislocate and remove global capital from any place, and all oversight, as the circulation of global capital among the superwealthy resists being parked or located in a national framework or onshore spaces, but can be invested in sites of excessive demand and overvalued property.

The “offshore” is the ultimate example of the uneven nature of the valuation of space in an age of income disparities, and a fiction to allow these income disparities to be preserved. It is the geographic manifestation of a logic of tax avoidance that has become the exclusive privileged operation of the superwealthy, who feel entitled to subtract their wealth from the community they live, escaping the demands of living in any nation by shifting their wealth–“parking” their luxury cars to secure parking places or garages–that guarantee tax-avoidance, and indeed sanction a geography of tax-avoidance that is the privileged exemption of the superwealthy, those of a guaranteed worth of $30 million for the next twenty years, a coterie of increasingly large size as a bracket, that in 2010 included 62,960 ultra-high-net-worth folks in North America; 54,325 in Europe; and 42,525 in the Asia-Pacific, per Wealth-X, with the latter predicted to leapfrog both by the 2030’s. havens located offshore currently enable the super-wealthy–the richest 0.01%–to evade 25% of owed income taxes, in a global scam that, per Gabriel Zucman and colleagues, effectively conceals over 40% of their personal fortunes, rendering them opaque to any national government, and as a consequence erodes claims to national sovereignty, and indeed the authority of the post-Westphalian state that was defined by its borders. If the map of territorial waters loosened national authority from borders to accommodate a global economic playing field allowing actual offshore mineral extraction–in what were felicitously termed “international waters, free from taxation, and outside the nation-state.

The rise of the “offshore” as an geoepistemic category, or “geoepistemology,” in Bill Rankin’s terms, effectively legitimized by the broad “tax amnesties” granted by multiple governments extended to tax cheats after the 2008-2009 financial crisis. The amnesties from sovereign taxes many–even before the release of the Panama papers–to for the first time try to “to map out the frequency of tax avoidance, by income level” that was long unmapped, first among Scandinavian countries, to start to plot the range of financial subterfuges and conceits that removed the wealth of the super-rich from any actual tax franchise, affirming the existence of a perilously increasing wealth inequality: in America alone, the disappearance of a “tax gap” that only between 2008-10 amounted to a massive $406-billion between what taxpayers owed Uncle Sam and what they actually paid. This removed their wealth from the territory, and indeed from the sovereignty, that create a deep crisis in the form of a time bomb for the sovereign state, making conceits of “tarriffs” and “imports” almost pale as a lower level of financial transactions occuring in real time, or on the books, rather than offshore.

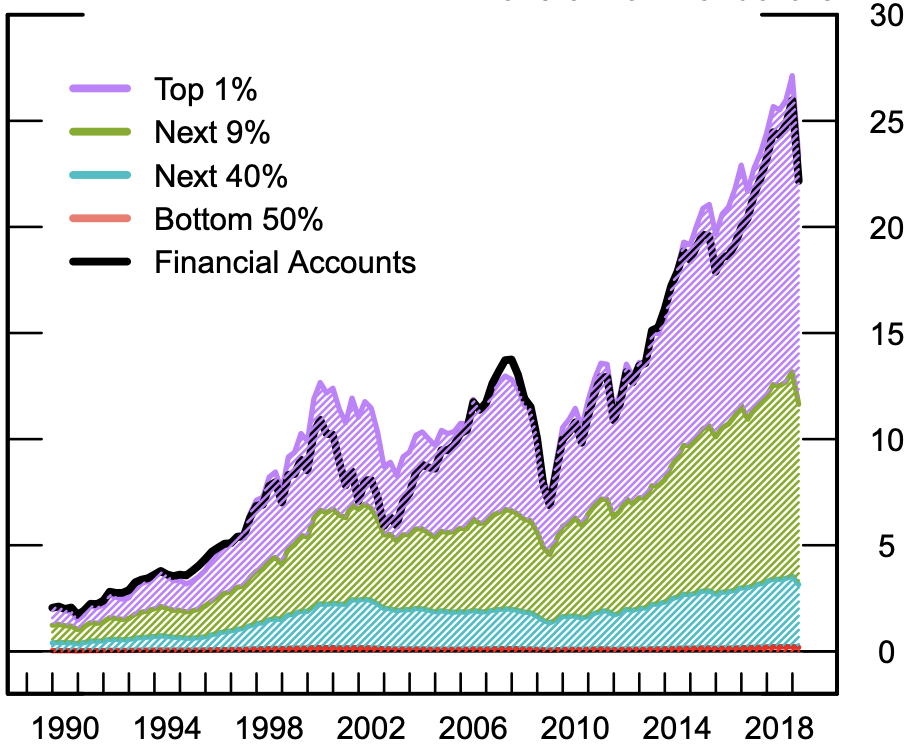

Is there any surprise that no moral authority existed able to compel Donald Trump to reveal his actual tax returns as U.S. President, when a gap of such proportions was the norm in the Obama era? The decreased in likelihood that America’s millionaires would ever find their returns audited have dropped up 80 percent than in 2011, suggesting a tacit acceptance of a gap in wealth that the geography of the offshore perpetuates and enables. Even after the stock market’s boom and bust cycles, returns of the upper 1% jumped in capital gains for mutual funds and financial accounts–measured in trillions of dollars in the last decade–that only solidified wealth inequality as a reality.

New stratospheric wealth levels pushed the collective net worths of the 1% considerably north of a hundred trillion; these rates of return were both not shared by other income groups, and not able to be comprehended by them. And such wealth generation granted rights to park wealth in an exclusively available geography of tax evasion of an expanded offshore constellation of money managers, outside sovereign reach; they would be no longer beholden to sovereign taxation agencies and were without obligation to states. The concentration of a hundred and twenty trillion in the wealth of the upper 1% created new spaces for wealth, apart from sovereign surveillance, where they might accumulate and grow, unable to be tracked in the global projections by which we are used to monitor other global events.

If the notion of the offshore is a relic of the post-colonial era–and began as a legal clarification of the category of offshore jurisdictions or overseas dependencies, removed from the European colonial powers as they enjoyed a liminal connection to formerly colonizing states–but it is perhaps better understood as the hegemony of a new notion of financial empire and wealth inequality. Today’s offshore are an exclusive insider knowledge, not open to many, but accessible to all initiated in schemes of tax avoidance, brokered in a bespoke maner by agencies–as Mossack Fonseca–who exploit loopholes of international law and the financial fictions of the ius mari to enable clients to sequester vast sums from national oversight–lest financial transactions be mapped. The offshore ensures opacity ing financial mapping, or the ability to place vast sums of money off the table, that sanction frictionless cash flows off the map.

In a global economy whose cash flows are more difficult to detect or embody–based less on the face-to-face, and rooted in the borderless fiction of the friction-free, increased integration of markets open multiple loophole for syphoning off national tax franchises, facilitating the sequestering corporate money–as the wealth of super-rich long tolerated to hold accounts described euphoniously as offshore, or, even more opaquely, as overseas, opening up fantastic speculation as to what that might really mean.