American President Donald Trump claimed that his attempt to prevent visitors from seven countries entering the United States preserved Americans’ safety against what was crudely mapped as “Islamic terror” to “keep our country safe.” Trump has made no bones as a candidate in calling for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims” as among his most important priorities if elected President. The map the he has asked the nation to draw about who can enter the country–purportedly because they are “terrorist-prone” nations–a bizarre shorthand for countries unable to protect the United States from terrorism–as if this would guarantee greater safety within the United States. For as the Department of Homeland Security affirmed a need to thwart terrorist or criminal infiltration by foreign nationals, citing the porous borders of a country possessing “the world’s most generous immigration system” that has been “repeatedly exploited by malicious actors,” and located the dangers of terror threats from outside the country as a subject for national concern, provoking anxiety by its demonization of other states as national threats. And even though the eagerly anticipated “ban” lacks “any credible national security rationale” as governmental policy, given the problem of linking the radicalization of any foreign-born terrorist or extremists were only radicalized or identified as terrorists after having become Americans, country of citizenship seems an extremely poor prognostic or indicator of who is to be considered a national danger.

Such eager mapping of threats from lands unable to police emigration to the United States oddly recall Cold War fears of “globally coordinated propaganda program” Communist Parties posing “unremitting use of propaganda as an instrument for the propagation of Marxist-Leninist ideology” once affirmed with omniscience in works as Worldwide Communist Propaganda Activities. Much as such works invited fears for the scale and scope of Communist propaganda “in all parts of the world,” however, the executive order focusses on our own borders and the borders of selective countries in the new “Middle East” of the post-9/11 era. The imagined mandate to guard our borders in the new administration has created a new eagerness to map danger definitively, out of deep frustration at the difficulty with which non-state actors could be mapped. While allegedly targeting nations whose citizens are mostly of Muslim faith, the ban conceals its lack of foundations and unsubstantiated half-truths.

The renewal of the ban against all citizens of six countries–altered slightly from the first version of the ban in hopes it would successfully pass judicial review, claims to prevent “foreign terrorist entry” without necessary proof of the links. The ban seems intended to inspire fear in a far more broad geography, as much as it provides a refined tool based on separate knowledge. Most importantly, perhaps, it is rigidly two-dimensional, ignoring the fact that terrorist organizations no longer respect national frontiers, and misconstruing the threat of non-state actors. How could such a map of fixed frontiers come to be presented a plausible or considered response to a terrorist threats from non-state actors?

1. The travel ba focus on “Islamic majority states” was raised immediately after it was unveiled and discourse on the ban and its legality dominated the television broadcasting and online news. The suspicions opened by the arrival from Wall Street Journal editor-in-chief Gerard Baker that his writers drop the term “‘seven majority-Muslim countries'” due to its “very loaded” nature prompted a quick evaluation of the relation of religion to the ban that the Trump administration chose at its opening salvo in redirecting the United States presidency in the Trump era. Baker’s requested his paper’s editors to acknowledge the limited value of the phrase as grounds to drop “exclusive use” of the phrase to refer to the executive order on immigration, as if to whitewash the clear manner in which it mapped terrorist threats; Baker soon claimed he allegedly intended “no ban on the phrase ‘Muslim-majority country’” before considerable opposition among his staff writers–but rather only to question its descriptive value. Yet given evidence that Trump sought a legal basis for implementing a ‘Muslim Ban’ and the assertion of Trump’s adviser Stephen Miller that the revised language of the ban might achieve the “same basic policy outcome” of excluding Muslim immigrants from entering the country. But curtailing of the macro “Muslim majority” concealed the blatant targeting of Muslims by the ban, which incriminated the citizens of seven countries by association, without evidence of ties to known terror groups.

The devaluation of the language of religious targeting in Baker’s bald-faced plea–“Can we stop saying ‘seven majority Muslim countries’? It’s very loaded”–seemed design to disguise a lack of appreciation for national religious diversity in the United States. “The reason they’ve been chosen is not because they’re majority Muslim but because they’re on the list of countRies [sic] Obama identified as countries of concern,” Baker opined, hoping it would be “less loaded to say ‘seven countries the US has designated as being states that pose significant or elevated risks of terrorism,'” but obscuring the targeting and replicating Trump’s own justification of the ban–even as other news media characterized the order as a “Muslim ban,” and as directed to all residents of Muslim-Majority countries. The reluctance to clarify the scope of the executive order on immigration seems to have disguised the United States’ government’s reluctance to recognize the nation’s religious plurality, and unconstitutionality of grouping one faith, race, creed, or other group as possessing lesser rights.

It is necessary to excavate the sort of oppositions used to justify this imagined geography and the very steep claims about who can enter and cross our national frontiers. To understand the dangers that this two-dimensional map propugns, it is important to examine the doctrines that it seeks to vindicate. For irrespective of its alleged origins, the map that intended to ban entrance of those nations accused without proof of being terrorists or from “terror-prone” nations. The “Executive Order Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” defended as a legal extension of the President’s “rightful authority to keep our people safe,” purported to respond to a crisis in national security. The recent expansion of this mandate to “keep our people safe” against alleged immanent threats has focused on the right to bring laptops on planes without storing them in their baggage, forcing visitors form some nations to buy a computer from a Best Buy vending machine of the sort located in airport kiosks from Dubai to Abu Dhabi, on the grounds that this would lend greater security to the nation.

2. Its sense of urgency should not obscure the ability to excavate the simplified binaries that justify its imagined geography. For the ban uses broad brushstrokes to define who can enter and cross our national frontiers that seek to control discourse on terrorist danger as only a map is able to do. To understand the dangers that this two-dimensional map proposes, one must begin from examining the unstated doctrines that it seeks to vindicate: irrespective of its alleged origins, the map that intended to ban entrance of those nations accused without proof of being terrorists or from “terror-prone” nations. The “Executive Order Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” defended as a legal extension of the President’s “rightful authority to keep our people safe,” purported to respond to a crisis in national security. The recent expansion of this mandate to “keep our people safe” against alleged immanent threats has focused on the right to bring laptops on planes without storing them in their baggage, on the largeely unsubstantiated grounds that this would lend greater security to the nation.

The lack of compunction to attend to the religious plurality of the United States citizens bizarrely date such a purported Ban, which reveals a spatial imaginary that run against Constitutional norms. In ways that recall exclusionary laws based on race or national origin from the early twentieth century legal system, or racial quotas Congress enacted in 1965, the ban raises constitutional questions with a moral outrage compounded as many of the nations cited–Syria; Sudan; Somalia; Iran–are sites from refugees fleeing Westward or transit countries, according to Human Rights Watch, or transit sites, as Libya. The addition to that list of a nation, Yemen, whose citizens were intensively bombed by the United States Navy Seals and United States Marine drones in a blitz of greater intensity than recent years suggests particular recklessness in bringing instability to a region’s citizens while banning its refugees. Even in a continued war against non-state actors as al Qaeda or AQAP–al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula–the map of Trump’s long-promised “Islamic Ban” holds sovereign boundaries trump human rights or humanitarian needs.

The ban as it is mapped defines “terror-prone regions” identified by the United States will only feed and recycle narratives of western persecution that can only perpetuate the urgency of calls for Jihad. Insisting national responsibility preventing admission of national citizens of these beleaguered nations placed a premium on protecting United States sovereignty and creates a mental map that removes the United States for responsibility of military actions, unproductively and unwarrantedly demonizing the nations as a seat of terrorist activity, and over-riding pressing issues of human rights tied to a global refugee crisis. But the mapping of a ban on “Foreign Terrorist Entry” into the United States seems to be something of a dramaturgical device to allege an imagined geography of where the “bad guys” live–even a retrograde 2-D map, hopelessly antiquated in an age of data maps of flows, trafficking, and population growth, provides a reductive way to imagine averting an impending threat of terror–and not to contain a foreign threat of non-state actors who don’t live in clearly defined bounds or have citizenship. Despite an absolute lack of proof or evidence of exclusion save probable religion–or insufficient vetting practices in foreign countries–seems to make a threat real to the United States and to magnify that threat for an audience, oblivious to its real effects.

For whereas once threats of terror were imagined as residing within the United States from radicalized regions where anti-war protests had occurred, focussed on Northern California, Los Angeles, Chicago, and the northeastern seaboard and elite universities–and a geography of home-grown guerrilla acts undermining governmental authority and destabilizing the state by local actions designed to inspire a revolutionary “state of mind,” which the map both reduced to the nation’s margins of politicized enclaves, but presented as an indigenous danger of cumulatively destabilizing society, inspired by the proposition of entirely homegrown agitation against the status quo:

Unlike the notion of terrorism as a tactic in campaigns of subversion and interference modeled after a revolutionary movement within the nation, the executive order located demons of terror outside the United States, if lying in terrifying proximity to its borders. The external threats call for ensuring that “those entering this country will not harm the American people after entering, and that they do not bear malicious intent toward the United States and its people” fabricate magnified dangers by mapping its location abroad.

2. The Trump administration has asserted a need for immediate protection of the nation, although none were ever provided in the executive order. The arrogance of the travel ban appears to make due on heatrical campaign promises for “a complete and total ban” on Muslims entering the United States without justification on any legitimate objective grounds. Such a map of “foreign terrorists” was most probably made for Trump’s supporters, without much thought about its international consequences or audience, incredible as this might sound, to create a sense of identity and have the appearance of taking clear action against America’s enemies. The assertion that “we only want to admit people into our country who will support our country, and love–deeply–our people” suggested not only a logic of America First, but seemed to speak only to his home base, and talking less as a Presidential leader than an ideologue who sought to defend the security of national boundaries for Americans as if they were under attack. Such a verbal and conceptual map in other words does immense work in asserting the right of the state to separate friends from enemies, and demonize the members of nations that it asserts to be tied to or unable to vet the arrival of terrorists.

The map sent many scrambling to find a basis in geographical logic, and indeed to remap the effects of the ban, if only to process its effects better.

But the broad scope of the ban which seems as if it will have the greatest effect in alienating other nations and undermining our foreign policy, as it perpetuates a belief in an opposition between Islam and the United States that is both alarming and disorienting. The defense was made without justifying the claims that he made for the links of their citizens to terror–save the quite cryptic warning that “our enemies often use our own freedoms and generosity against us”–presumes that the greatest risks not only come from outside our nation, but are rooted in foreign Islamic states, even as we have been engaged for the past decade in a struggle against non-state actors. In contrast to such ungratefulness, Trump had repeatedly promised in his campaign to end definitively all “immigration from terror-prone regions, where vetting cannot safely occur,” after he had been criticized for calling during the election for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” until they could “figure out what is going on.”

But the targeted audience was always there, and few of his supporters were likely to have forgotten the earlier claims–and the origins of this geographical classification of national enemies terrifying that offers such a clear dichotomy along national lines. While pushed to its logical conclusion, the ban on travel could be extended to the range of seventy-odd nations that include a ban against nations associated with terrorism or extremist activity–

–but there is a danger in attributing any sense of logical coherence to Trump’s executive order in its claims or even in its intent. The President’s increasing insistence on his ability to instate an “extreme vetting” process–which we do not yet fully understand–seems a bravado mapping of danger, with less eye to the consequences on the world or on how America will be seen by Middle Eastern nations, or in a court of law. The map is more of a gesture, a provocation, and an assertion of American privilege that oddly ignores the proven pathways of the spread of terrorism or its sociological study.

But by using a broad generalization of foreign nations as not trustworthy in their ability to protect American interests to contain “foreign terrorists”–a coded generalization if there ever was one–Trump remapped the relation of the United States to much of the world in ways that will be difficult to change. For in vastly expanding the category “foreign terrorists” to the citizens of a group of Muslim-majority nations, he conceals that few living in those countries are indeed terrorists–and suggests that he hardly cares. The executive order claims to map a range of dangers present to our state not previously recognized in sufficient or honest ways, but maps those states in need as sites of national danger–an actual crisis in national security he has somehow detected in his status as President–that conceal the very sort of non-state actors–from ISIS to al-Qaeda–that have targeted the United States in recent years. By enacting a promised “complete and total ban” on the entry of Muslims from entering the nation sets a very dangerous precedent for excluding people from our shores. The targeting of six nations almost exemplifies a form of retributive justice against nations exploited as seats of terrorist organizations, to foment a Manichean animosity between majority Muslim states and the United States–“you’re either with us, or you’re against us”–that hardly passes as a foreign policy map.

Rather than respecting or prioritizing human rights, the identification of Islam with terrorist organizations seems the basis for excluding citizens and nationals of seven nations who might allow “foreign terrorist entry.” The ban was quickly noted that the list of nations pointedly excluded those where Trump did or pursued business as a businessman and hotelier. But while not acknowledging this distinction, it promotes a difference between “friend” and “enemy” as a remapping of threats to the nation along national lines, targeting nations not only as suspicious sites of radicalization, but by collectively prohibiting their residents and nationals from entry to the nation. While it is striking that President Jimmy Carter had targeted similar states identified as the nations that “have repeatedly provided support for acts of international terrorism” back in 1980–President Carter cited the long-unstable nations of Iraq, Libya, South Yemen, and Syria, following then-recent legislation indicating their abilities “support acts of international terrorism.” The near-identical mapping of terror does not exemplify an egregious instance of “mission creep,” but by blanketing of such foreign nationals as “inadmissible aliens” without evidence save “protecting the homeland” suggests an unimaginable level of xenophobia–toxic to foreign relations, and to anyone interested in defending national security. It may Israeli or Middle Eastern intelligence poorly mapped the spread of growing dangers.

But it echoes strikingly similar historical claims to defend national security interests have long disguised the targeting of groups, and have deep Cold War origins, long tied to preventing entrance of aliens with dangerous opinions, associations or beliefs. It’s telling that attorneys generals in Hawai’i and California first challenged the revised executive order–where memories survives of notorious Presidential executive order 9006, which so divisively relocated over 110,000 Japanese Americans to remote areas, the Asian Exclusion Act, and late nineteenth-century Chinese Exclusion Act, which limited immigration, as the Act similarly selectively targets select Americans by blocking in unduly onerous ways overseas families of co-nationals from entering the country, and establishes a precedent for open intolerance of the targeting the Muslims as “foreign terrorists” in the absence of any proof.

The “map” by which Trump insists that “malevolent actors” in nations with problems of terrorism be kept out for reasons of national security mismaps terrorism, and posits a false distinction among nation states, but projects a terrorist identity onto states which Trump’s supporters can take satisfaction in recognizing, and delivers on the promise that Trump had long ago made–in his very first televised advertisements to air on television–to his constituents.

from Donald Trump’s First Campaign Ad (2016)

from Donald Trump’s First Campaign Ad (2016)

Such claims have been transmuted, to members of a religion in ways that suggest a new twist on a geography of terror around Islam, and the Trump’s bogeyman of “Islamic terror.” Although high courts have rescinded the first version of the bill, the obstinance of Trump’s attempt to map dangers to America suggests a mindset frozen in an altogether antiquated notion of national enemies. Much in the way that Cold War governments prevented Americans from travel abroad for reasons of “national security,” the rationale for allowing groups advocating or engaging in terrorist acts–including citizens of the countries mapped in red, as if to highlight their danger, below–extend to a menace of international terrorism now linked in extremely broad-brushed terms to the religion of Islam–albeit with the notable exceptions of those nations with which the Trump family has conducted business.

The targeting of such nations is almost an example of retributive justice for having been used as seats of terrorist organizations, but almost seek to foment a Manichean animosity between majority Muslim states and the United States, and identify Islam with terror– “you’re either with us, or you’re against us“–that hardly passes as a foreign policy map. The map of the ban offers an argument from sovereignty that overrides one of human rights.

3. It should escape no one that the Executive Order on Immigration parallels a contraction of the provision of information from intelligence officials to the President that assigns filtering roles of new heights to Presidential advisors to create or fashion narratives: for as advisers are charged to distill global conflicts to the dimensions of a page, double-spaced and with all relevant figures, such briefings at the President’s request give special prominence to reducing conflicts to the dimensions of a single map. Distilled Daily Briefings are by no means fixed, and evolve to fit situations, varying in length considerably in recent years accordance to administrations’ styles. But one might rightly worry about the shortened length by which recent PDB’s provide a means for the intelligence community to adequately inform a sitting President: Trump’s President’s Daily Briefing reduce security threats around the entire globe to one page, including charts, assigning a prominent place to maps likely to distort images of the dangers of Islam and perpetuated preconceptions, as those which provide guidelines for Border Control.

In an increasingly illiberal state, where the government is seen less as a defender of rights than as protecting American interests, maps offer powerful roles of asserting the integrity of the nation-state against foreign dangers, even if the terrorist organizations that the United States has tired to contain are transnational in nature and character. For maps offer particularly sensitive registers of preoccupations, and effective ways to embody fears. They offer the power to create an immediate sense of territorial presence within a map serves well accentuate divides. And the provision of a map to define how the Muslim Ban provides a from seven–or from six–countries is presented as a tool to “protect the American people” and “protecting the nation from foreign terrorist entry into the United States” offers an image targeting countries who allegedly pose dangers to the United States, in ways that embody the notion. “The majority of people convicted in our courts for terrorism-related offenses came from abroad,” the nation was seemed to capitalize on their poor notions of geography, as the President provided map of nations from which terrorists originate, strikingly targeting Muslim-majority nations “to protect the American people.”

Yet is the current ban, even if exempting visa holders from these nations, offers no means of considering rights of entry to the United States, classifying all foreigners from these nations as potential “foreign terrorists” free from any actual proof.

Is such an open expenditure of the capital of memories of some fifteen years past of 9/11 still enough to enforce this executive order on the nebulous grounds of national safety? Even if Iraqi officials seem to have breathed a sigh of relief at being removed from Muslim Ban 2.0, the Manichean tendencies that underly both executive orders are feared to foster opposition to the United States in a politically unstable region, and deeply ignores the multi-national nature of terrorist groups that Trump seems to refuse to see as non-state actors, and omits the dangers posed by other countries known to house active terrorist cells. In ways that aim to take our eyes off of the refugee crisis that is so prominently afflicting the world, Trump’s ban indeed turns attention from the stateless to the citizens of predominantly Muslim nation, limiting attention to displaced persons or refugees from countries whose social fabric is torn by civil wars, in the name of national self-interest, in an open attempt to remap the place of the United States in the world by protecting it from external chaos.

The map covered the absence of any clear basis for its geographical concentration, asserting that these nations have “lost control” over battles against terrorism and force the United States to provide a “responsible . . . screening” of since people admitted from such countries “may belong to terrorist groups. ” Attorney General Jeff Sessions struggled to rationalize its indiscriminate range, as the nations “lost control” over terrorist groups or sponsored them. The map made to describe the seven Muslim-majority nations whose citizens will be vetted before entering the United States. As the original Ban immediately conjured a map by targeting seven nations, in ways that made its assertions a pressing reality, the insistence on the six-nation ban as a lawful and responsible extension of executive authority as a decision of national security, but asked the public only to trust the extensive information that the President has had access to before the decree, but listed to real reasons for its map. The maps were employed, in a circular sort of logic, to offer evidence for the imperative to recognize the dangers that their citizens might pose to our national security as a way to keep our own borders safe. The justification of the second iteration of the Ban that “each of these countries is a state sponsor of terrorism, has been significantly compromised by terrorist organizations, or contains active conflict zones” stays conveniently silent about the broad range of ongoing global conflicts in the same regions–

Armed Conflict Survey, 2015

Armed Conflict Survey, 2015

–or the real index of terrorist threats, according to the Global Terrorism Index (GTI), compiled by the Institute for Economics and Peace—

Institute for Economics and Peace

Institute for Economics and Peace

–but give a comforting notion that we can in fact “map” terrorism in a responsible way, and that the previous administration failed to do so in a responsible way. With instability only bound to increase in 2017, especially in the Middle East and north Africa, the focus on seven or six countries whose populace is predominantly Muslim seems a distraction from the range of recent terrorist attacks across a broad range of nations, many of which are theaters of war that have been bombed by the United States.

The notion of “keeping our borders safe from terrorism” was the subtext of the map, which was itself a means to make the nation safe as “threats to our security evolve and change,” and the need to “keep terrorists from entering our country.” For its argument foregrounds sovereignty and obscures human rights, leading us to ban refugees from the very same lands–Yemen–that we also bomb.

For the map in the header to this post focus attention on the dangers posed by populations of seven predominantly Muslim nations declared to pose to our nation’s safety that echo Trump’s own harping on “radical Islamic terrorist activities” in the course of the Presidential campaign. By linking states with “terrorist groups” such as ISIS (Syria; Libya), al-Qaeda (Iran; Somalia), Hezbollah (Sudan; Syria), and AQAP (Yemen), that have “porous borders”–a term applied to both Libya, Sudan and Yemen, but also applies to Syria and Iran, whose governments are cast as “state sponsors” of terrorism–the executive orders reminds readers of our own borders, and their dangers of infiltration, as if terrorism is an entity outside of our nation. That the states mentioned in the “ban” are among the poorest and most isolated in the region is hardly something for which to punish their citizens, or to use to create greater regional stability. (The citation in Trump’s new executive order of the example of a “native of Somalia who had been brought to the United States as a child refugee and later became a naturalized United States citizen sentenced to thirty years [for] . . . attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction as part of a plot to detonate a bomb at a crowded Christmas-tree-lighting ceremony” emphasizes the religious nature of this threats that warrant such a 90-day suspension of these nationals whose entrance could be judged “detrimental to the interests of the United States.”)

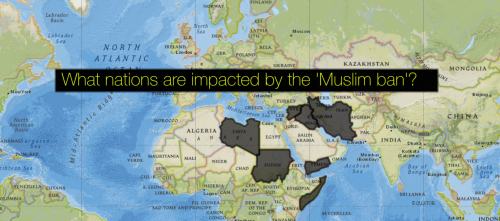

4. It’s not coincidental that soon after we quite suddenly learned about President Trump’s decision to ban citizens or refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries before the executive order on immigration and refugees would released, or could be read, maps appeared on the nightly news–notably, on both FOX and CNN–that described the ban as a fait accompli, as if to deny the possibility of resistance to a travel prohibition that had been devised by members of the executive without consultation of law makers, Trump’s own Department of State, or the judiciary. The map affirmed a spatial divide removed from judicial review. Indeed, framing the Muslim Ban in a map not that tacitly reminds us of the borders of our own nation, their protection, and the deep-lying threat of border control. Although, of course, the collective mapping of nations whose citizens are classified en masse as threats to our national safety offers an illusion of national security, removed from the actual paths terrorists have taken in attacks plotted in the years since 9/11–

–or the removal of the prime theater of terrorist attacks from the United States since 9/11. The specter of terror haunting the nation ignores the actual distribution of Al Qaeda affiliates cells or of ISIS, let alone the broad dissemination of terrorist causes on social media.

For in creating a false sense of containment, the Ban performs of a reassuring cartography of danger for Trump’s constituents, resting on an image of collective safety–rather than actual dangers. The Ban rests on a conception of executive privilege nurtured in Trump’s cabinet that derived from an expanded sense of the scope of executive powers, but it may however provide an unprecedented remapping the international relations of the United States in the post-9/11 era; it immediately located dangers to the Republic outside its borders in what it maps as the Islamic world, that may draw more of its validity as much from the geopolitical vision of the American political scientist Samuel P. Huntington as it reflects current reality, and it offers an unclear map of where terror threats exist. In the manner that many early modern printed maps placed monsters at what were seen as the borders of the inhabited world, the Islamic Ban maps “enemies of the state” on the borders of Western Civilization–and on what it sees as the most unstable borders of the larger “Muslim world”–

–as much as those nations with ISIL affiliates, who have spread far beyond any country.

But by playing the issue as one of nations that are responsible for maintaining their own borders, Trump has cast the issue of terrorism as one of border security, in ways perhaps close to his liking, and which plays to his constituency’s ideas of defending America, but far removed from any sense of the international networks of terror, or of the communications among them. Indeed, the six- or seven-nation map that has been proposed in the Muslim Ban and its lightly reworked second version, Ban 2.0, suggest that terrorism is an easily identifiable export, that respect state lines, while the range of fighters present in Syria and Iraq suggest the unprecedented global breadth that these conflicts have won, extending to Indonesia and Malaysia, through the wide-ranging propaganda machine of the Islamic State, which makes it irresponsibly outdated to think about sovereign divisions and lines as a way for “defending the nation.”

Trump rolled out the proposal with a flourish in his visit to the Pentagon, no doubt relishing the photo op at a podium in the center of military power on which he had set his eyes. No doubt this was intentended. For Trump regards the Ban as a “border security” issue, based on an idea of criminalizing border crossing that he sees as an act of defending national safety, as a promise made to the American people during his Presidential campaign. As much as undertake to protect the nation from an actual threat, it created an image of danger that confirmed the deepest hunches of Trump, Bannon, and Miller. For in ways that set the stage for deporting illegal immigrants by thousands of newly-hired border agents, the massive remapping of who was legally allowed to enter the United States–together with the suspension of the rights of those applying for visas as tourists or workers, or for refugee status–eliminated the concept of according any rights for immigrants or refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries on the basis of the danger that they allegedly collectively constituted to the United States. The rubric of “enhancing public safety within the interior United States” is based on a new way of mapping the power of government to collectively stigmatize and deny rights to a large section of the world, and separate the United States from previous human rights accords.

It has escaped the notice of few that the extra-governmental channels of communication Trump preferred as a candidate and is privileging in his attacks on the media indicates his preference for operating outside established channels–in ways which dangerously to appeal to the nation to explain the imminent vulnerabilities to the nation from afar. Trump has regularly claimed to undertake “the most substantial border security measures in a generation to keep our nation and our tax dollars safe” in a speech made “directly to the American people,” as if outside a governmental apparatus or legislative review. And while claiming to have begun “the most substantial border security measures in a generation to keep our nation and our tax dollars safe” in speeches made “directly to the american people with the media present, . . . because many of our reporters . . . will not tell you the truth,” he seems to relish the declaration of an expansion of policies to police entrance to the country, treating the nation as if an expensive nightclub or exclusive resort, where he can determine access by policies outside a governmental apparatus or legislative review. Even after the unanimous questioning by an appellate court of the constitutionality of the executive order issued to bar both refugees and citizens of seven Muslim-majority nations, Trump insists he is still “keeping every option open“ and on the verge this coming week of “just filing a brand new order“ designed to leave more families in legal limbo and refugees safely outside of the United States. The result has been to send waves of fear among refugees already in the Untied States about their future security, and among refugees in camps across the Middle East. The new order–which exempts visa holders from the nations, as well as green card holders, and does not target Syrian refugees when processing visas–nonetheless is directed to the identical seven countries, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Sudan and Libya, while retaining a policy of or capping the number of refugees granted citizenship or immigrant status, taking advantage of a linguistic slippage between the recognition of their refugee status and the designation as refugees of those fleeing their home countries.

While the revised Executive Order seems to restore the proposed ceiling of 50,000 refugees chosen in 1980 for those fleeing political chaos with “well-founded fears of persecution,” the new policy, unlike the Refugee Act of 1980, makes no attempt to provide a flexible mechanism to take account of growing global refugee problems even as it greatly exaggerates the dangers refugees admitted to America pose, and inspires fear in an increasingly vulnerable population of displaced peoples.

For Trump’s original Executive Order on Immigration rather openly blocks entry to the country in ways that reorient the relation of the United States to the world. It disturbingly remaps our national policy of international humanitarianism, placing a premium on our relation to terrorist organizations: at a stroke, and without consultation with our allies, it closes our borders to foreign entry to all visa holders or refugees in something more tantamount to a quarantine of the sort that Donald Trump advocated in response to the eruption of infections from Ebola than to a credible security measure. The fear of attack is underscored in the order.

5. The mapping of danger to the country is rooted in a promise to “keep you safe” that of course provokes fears and anxieties of dangers, as much as it responds to an actual cause. And despite the stay on restraints of immigrations for those arriving from the seven countries whose residents are being denied visas by executive fiat, the drawing of borders under the guise of “extreme vetting,” and placing the dangers of future terrorist attacks on the “Homeland” in seven countries far removed from our shores, as if to give the nation a feeling of protection, even if our nation was never actually challenged by these nations or members of any nation state.

The result has already inspired fear and panic among many stranded overseas, and increase fear at home of alleged future attacks, that can only bolster executive authority in unneeded ways.

The genealogy of executive prerogatives to defend the borders and bounds of the nation demands to be examined. Even while insisting on the need for speed, security, and unnamed dangers, the Trump administration continues to accuse the courts of having made an undue “political decision” in ways that ignore constitutional due process by asserting executive prerogative to redraw the map of respecting human rights and mapping the long unmapped terrorist threats to the nation to make them appear concrete. For while the dangers of terrorist attack were never mapped with any clear precision for the the past fifteen years since the attacks of Tuesday, September 11, 2001, coordinated by members of the Islamic terrorist group al-Qaeda, Trump has misleadingly promised a clear remapping of the dangers that the nation faces, which he insists hat the nation and his supporters were long entitled to have, as if meeting the demand to remap the place of terrorism in an increasingly dangerous world.

The specter of civil rights violations of a ban on Muslims entering the United States had been similarly quite abruptly re-mapped the actual relation of the United States to the world, in ways that evoke the PATRIOT act, by preventing the entry of all non-US residents from these nations. Much as the PATRIOT act led to the detention of Arab and Muslim suspects, even without evidence, the executive order that Trump issued banned all residents of these seven Muslim-majority nations. The above map, which was quickly shown on both FOX and CNN alike to describe the regions identified as sites of potential Jihadi danger immediately oriented Americans to the danger of immigrants as if placing the country on a state of yellow alert. There is some irony hile terrorist networks have rarely been mapped with precision–and are difficult to target even by drone strikes, the executive order goes far beyond the powers granted to immigration authorities to allow the “territoritorial integrity of the United States,” even as the territory of the United States is of course not actually under attack.

What sort of world do Trump and his close circle of advisors live–or imagine that they live? “It is about keeping bad people (with bad intentions) out of the country,” Trump tried to clarify on February 1, as the weekend ended. We’re all too often reminded that it was all about “preventing foreign terrorists from entering the United States,” as Trump insists, oblivious to the bluntness of a blanket targeting of everyone with a visa or citizenship from seven nations of Muslim majority–a blunt criteria indeed–often not associated with specific terrorist threats, and far fewer than Muslim-majority nations worldwide. Of course, the pressing issue of the need to enact the ban seem to do a psychological jiu jitsu of placing terrorist threats abroad–rooting them in Islamic communities in foreign lands–despite a lack of attention to the radicalization of many citizens in the United States, making their vetting upon entry or reentry into the country difficult–confirmed by the recent conclusion that, in fact, “country of citizenship [alone] is unlikely to be a reliable indicator of potential terrorist activity.” So what use is the map?

As much as focussing on the “bad apples” among all nations with a predominance of Muslim members–

–it may reflect the tendency of the Trump administration to rely on crude maps to try to understand and represent complex problems of global crises and events, for a President whose staff seems to be facing quite a steep on-the-job learning curve, adjusting their expectations and vitriol to policy making with some difficulty. The recent revelation of Trump’s own preference for declarative maps within his daily intelligence briefings–a “single page, with lots of graphics and maps” according to one official familiar with his daily intelligence briefings–not only indicate the possibility that executive order may have indeed developed after consulting maps, but underscore the need to examine the silences that surround its blunt mapping of terrorism. PDB’s provide distillations of diplomatic, intelligence, and military information, and could include interactive maps or video when President Obama received PDB’s on his iPad, even encouraging differing or dissenting opinions. They demand disciplined attention as a medium, lest one is distracted by uncorroborated information or raw intelligence—or untrained in discriminating voices from different areas of expertise.

Is the synthesis an act of intellectual engagement Trump is experienced? Given his longstanding plans to limit the role of a Director of National Intelligence, tasked to synthesize the sixteen intelligence offices in government, and the confirmation of the Director after the Executive Order was issued, Trump most probably based the decision on the information-gathering system developed on the campaign trail.

6. The sudden and dramatic shrinkage of the increasingly streamlined Presidential Daily Briefings to but a page omits more information than it is bound to include, and may give some sign about the resurgence of a 2-D map in the Trump administration. As maps are apt all the more to mislead–and indeed, to present and privilege only a single point of view–Trump prefers the inclusion of a map within increasingly streamlined Presidential Daily Briefings from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, without dissenting views or conflicting opinions. While continuing a brief summary of recent breaking events deserving Presidential attention, and are given to the President-Elect to allow she or he to get “up to speed” with global events, tand for the intelligence community to prevent the President’s team and administration to “settle into a narrative” of policy-making: the regular provision of the PDB provides intelligence officials an opportunity to challenge the worldview of the president-elect’s political advisers with a dose of reality. Former CIA Director Michael Hayden described its provision as the “phenomenon of the unpleasant fact,” when “You’re telling them something they don’t want to hear and don’t want to believe” to challenge their world view, delivered in -person “to shake the preferred narrative of the policymaker,” and to do so “with your tone, and your words and your body language to communicate, as opposed to just throwing it over the transom.”

Already as President Elect, Trump revealed not only ambivalence to the standard routes or channels of intelligence-provision–“I get it when I need it,” Trump told Fox News Sunday–and a certain arrogance, rather than hearing from a broad array of experts. Its focus reflects a geographic preoccupation or concern: if President Nixon’s briefing focussed on Vietnam and China; Ronald Reagan’s was almost singularly obsessed with the Soviet Union; recent PDB’s focus largely on the Middle East and Russia. While the extent of such briefings have varied in length considerably, one rightly worries about their shortened character as a conduit from the intelligence community: just how much gets through, and how much conforms to preconceptions? For such maps suit the purpose of foregrounding one perspective, if they digest information in a way easy to understand. The immorality of the ban on visitors and refugees from seven countries is a gift to hard-line rulers, rather than effecting terrorism. But it bears noting that the Travel Ban may actually reflect the currency of anti-Muslim conspiracy theories within Trump’s cabinet: for Bannon, a former film-maker turned Breitbart executive, has distortingly labeled Muslim-American groups as “cultural jihadists” intent on destroying American society and Western Civilization, in the past offered a podium to groups Americans of the cultural danger of Islam, hoping to make Americans feel threatened by Muslim organizations. His planned 2007 bizarre proposal for a film conjuring the spectre of America’s takeover by an Islamic “Fifth Column” about a Muslim takeover that produced a regime change that lead to the imposition of Sharia religion–The Islamic States of America, which set a bizarre precedent for the willful conflation of the legal code of Islam with a terrorist threat. Bannon’s proposed film script may seem a bizarrely indulgent fantasy, but led Bannon to caution against the threat of the “Muslim World” in the Vatican in 2014, asserting “There is a major war brewing, a war that’s already global.” He has now gained a platform for airing his views, irrespective of civil liberties.

Is the notion of such a threat behind Trump’s proposed Islamic Ban, and the image of “unifying the country” the Trump puts forth? Indeed, in singling out Muslims to whom it attributes “hostile attitudes toward it and its founding principles” of the United States, as “those who would place violent ideologies over American law,” the conjuring of Shariah law as a separate civilization and tradition creates not only a narrative that opposes Islam and the West, but Islamic nations against the United States of America, giving validity to anti-Muslim rhetoric, and the bluntness of Bannon’s own views that ‘Christianity is dying in Europe and Islam is on the rise,” and lends currency to the anti-Islamic fears of the threat Islamic codes posed to American freedom of the sort Bannon fostered in his film, and in the fake news that circulated on Breitbart News of a “stealthy, subversive jihad.” Indeed, wrapping anti-Islamism in patriotic rhetoric encourage the urgency of containing “Radical Islam” as a way to purge, cleanse, or protect our nation, society and culture from impending threats, and of conflating religion and state in truly un-American ways.

In a manner far removed from American foreign policy expertise, the recent ‘Islamic Ban’ unjustifiably maps the danger of Islamicist menace, however. And its fears have been echoed by the bizarre insistence that its suspension has already allowed an “onrush” of refugees from seven “suspect” nations to occur, in ways that frame a geography of distrust and spatial imaginary of national vulnerability in urgent and quite dangerous ways.

In ways that recall the sudden large scale “detention without bond” of Arab and Muslim non-citizens in the panicked months after 9/11, as ad hoc laws legitimated the “haphazard and indiscriminate” suspected terrorists, the expansion of the executive prerogative mirrors presumption until proven otherwise of large numbers of non-citizen residents and foreigners. Detention until presumed relation to the threat of terrorism was proven, or the suspect removed from the nation, in the PATRIOT Act during the Bush administration was expanded grounds for immigrants’ detention for national safety, as the denial of all visas or recognition of refugees from war-torn regions as Syria, Sudan, and Iraq–all without ties to terrorist networks–was suddenly decreed. The executive order erased individuals’ guilt or actual involvement by subsuming their fate within a question of border security and national security.

By suspending civil rights and refugee processing in order to “ensure our immigration system is not a vehicle for terrorists,” national dangers needed to be mapped. The definition of seven nations asserted the perception of a source for danger with no discernible legal basis, by naturalizing the citizens of these nations as enemies of danger to the state, in ways that seem to mask quite half-heartedly its targeting of members of the Islamic faith. For the executive order creates a map of terror to magnify actual threats of a terrorist strike on United States soil in unprecedented ways. Although the ban asserted only to allow faithful execution of immigration laws already on the books, and only to last three or four months, the practices of detainment until the threat of terrorist ties was in fact assessed has been radically expanded in the promotion of Islam into an existential threat by former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn, senior policy adviser Stephen Miller, and Steve Bannon. While President Trump, obliviously, has asserted the “very, very strict ban” was “working out very nicely,”the roll-out was not only disastrous, but placed many in places of panic, led flights to be cancelled, and others to be returned to their destinations or prevented from travel. The result was to implement a “Constitution-Free Zone” not only at our borders, but in our airports–oddly analogous to the shrunken borders of rights in this image of the zone where United States Custom and Border Protection agents operate, and enjoy broad powers and often justify warrantless searches.

While such warrantless searches are only conducted with “reasonable suspicion” in this border zone near “ports of entry,” the restrictions of entering the nation was intended to prevent all citizens of Islamic-Majority states without justification from entering the United States. And no sleight of hand is able better to convincingly manufacture and embody the danger of such an unidentifiable threat as a map. And the certainty by which the map demonstrates the ability by executive fiat to “suspend the entry” of “any class of aliens,” according to the Cold-War era Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 19522, judged “detrimental to the interest of the United States” has created a basis for invoking the territorial borders at the nation’s airports in ways oddly jarring in an age of international air travel. It seems all too fitting that the time-travel supposed President expands the detention of immigrants deemed dangerous to the nation in the PATRIOT Act, designating a broad range of nationals as in danger of exporting terror to the United States–in a particularly effective exercise of collective psychology. In ways that seem to spawn a newly increased level of fear–and to use fears to justify the new needs for national defense–Trump seems to have begun from a new attempt to map and concretize the existence of actual threats that endanger our democracy, albeit in quite disproportionately exaggerated and deeply unjustified ways.

The map of “nations impacted” by what was designated in shorthand as a “Travel Ban”that policy adviser Miller called “beyond question” was widely mapped as covering an expanded region identified as dangerous to the nation’s domestic security. The residents have been placed at a pen-stroke at a collective remove from the United States that will be difficult to bridge for some time, even if the executive order designed to obstruct mobility and travel has been issued to play to audiences of Trump supporters at home. Trump is said to be fond of maps, requesting multiple maps and graphics in single-page policy papers–“the President likes maps,” said an official in the Trump White House–and the direct signifying power of a map with clear borders seem to have provided him with the clearest way to get a handle on terrorist threats early in his administration.

If maps best show the “bad people” Trump wants to be kept out of the country, was the formulation of the executive order on refugees and visas outside traditional interagency processes, or operational guidance, made decisively on a map?

As much as a visa waiver, or a permanent ban on refugees, the deep international alienation that the executive order achieved is an arrogant strike against involvement in a region where the United States was until very recently not only militarily engaged, but whose civilian populations were quite heavily bombed. To be sure, the intent to issue a ban on Muslim refugees had been repeatedly raised on the campaign trail in 2016, enough to make it seem a reasonable proposition, if one without grounds. The notion was floated from Trump’s very first television advertisements of the campaign as an illustration of his promise to provide a total image of national safety –and, albeit misleadingly, to remove its vulnerability from external threats.

Although the Ban aims to remove the specter of a jihadist threat, it is based on a deeply disruptive reorientation of the map, designating many as enemies of the nation without any grounds. Yet it shares continuities with disturbing traditions granting exta-constitutional authority to an executive to defend us against the specter of external enemies.

Still from Donald Trump’s First Campaign Ad (2016)

Still from Donald Trump’s First Campaign Ad (2016)

While it was little surprise to hear an issue prominently raised in the Presidential campaign, without fact-checking or legal objections, the framing of the executive order without any consultation outside of a small circle of advisors familiar from Trump’s campaign have activated a profound remapping of the relation of the nation and its enemies, evoking a legacy of geopolitics that is far removed from any foreign policy expertise, enhancing the executive power of an executive with very limited foreign policy experience. Rather than be only a disruption from past foreign policy, the issuance of the slew of executive orders serves to amplify the power of the executive in troubling continuity with the presidency of George W. Bush and the legal precedents of enhancing executive authority to define enemies of the nation that echo the ideologue and jurist Carl Schmitt’s defense of executive power beyond constitutional limits during states of emergency. And even though members of the Trump cabinet insist that Steven Bannon, considered a driving force behind Trump’s immigration policies, had “no role” in the executive order on immigration and refugees that “have profoundly improved our national security,”and more are intended to protect the country from “hostile” intruders. But the fear-inspiring map of vulnerabilities to Jihadist that the Ban creates seems an attempt to undo alliances carefully forged against ISIS.

Even as Trump’s senior policy advisers assert the ideological differences of their attitudes to the protection of the nation’s borders, they descend from an authoritarian claim for executive prerogative to redraw foreign policy maps for domestic safety. Yet Trump’s senior policy advisers assert on FOX TV and Sunday morning television news “the president’s powers here are beyond question” to designate national enemies to secure our borders necessary to national safety, affirming the power of the executive to protect national safety in distinctly un-American and anti-democratic disparagement of legal authority or review, shrouded in an imbalanced notion of constitutional authority, and mismaps the relation of the executive to the world with a fascist pedigree by “getting strong” against enemies. Some observers of the Trump campaign questioned the fascist origins of its xenophobic rhetoric, but insistence on the urgency of securing national borders of “suspend[ing] the entry of aliens” offers an exercise of boundary-drawing, defining others as outsiders irrespective of individual rights, in the name of defending “national” interests irrespective of individual rights.

Drew Angerer/Getty

Drew Angerer/Getty

The approval Donald Trump had sought from the crowds at his rallies as a candidate were presented as surrogates for a democratic process in particularly frightening ways. The proposal to ban immigrants from the country was validated as the opinion of his strongest supporters, in ways that over-rode existing governmental protocol or legal scrutiny. Although these seven nations are among the most war-torn areas with significant numbers of refugees arriving to the United States in recent years–and just less than half since the inauguration and in the last year–the order creates a map of American interests focussed on the dangers of immigration, mapping the dangers that refugees and foreigners pose to American interests that disrupts both refugee policy by barring the entrance of members of seven nations in any way that has become something of a centerpiece in defining the identity and agenda of a Trump administration, if not a testing point of executive authority–while dramatically increasing the distance of the entire region from the United States with terrifyingly dangerous consequences.

The quickness with which Trump’s January 27 executive order to “protect the American people from attacks by foreign nationals admitted to the United States” followed his first visit to the Pentagon that afternoon, when he had promised to introduce new “vetting measures to keep radical Islamic terrorists out of the United States of America.” The executive order on refugees and visas, and largely avoided the traditional interagency process but was issued during a visit to the Pentagon when Trump had promised, “We want to make sure we don’t want to admit into our country the very terrorists that our soldiers are fighting overseas.” In raising a national security issue, Trump used the military setting to set forth not only where the dangers to the United States lie, but to scapegoat a religious faith he had long associated with the dangers of jihad. In offering a map of seven nations, the executive order concretized the presence of danger outside the nation’s boundaries in ways particularly disturbing and over-eager, based on the shaky principle of mapping the danger “radical Islamists” posed as a national threat for future terrorist attacks from seven nations. The abrupt decision within a tight inner circle redirected foreign policy from within the White House–the white-haired Vice-President Pence, waxy Stephen Miller, Trump’s senior policy advisor, pale Gen. Mike Flynn and scrappy chief strategist Stephen K. Bannon–blindsiding top lawmakers, heads of the Homeland Security, State or Defense Departments, and courts.

The executive order framed a distorted map of nations threatening the country for the nation that was made without foreign policy expertise as a pillar of national policy, reflecting their fear of Islamists in ways that demands to be examined. In part, the executive order perpetuated the need to expand an already extremely rigorous vetting procedure, crating a sense of national dangers by casting the existing vetting practices of screening nationals of Islamic-majority states as both flawed and in disarray, to create a sense of panic that legitimized and called attention to the need for executive order. But far more dangerously, by disbanding all foreign policy expertise, the ban seems to rest on validating a deeply rooted anti-Islamist suspicion, leading senior advisors like Miller to inveigh against “judicial usurpation of power” as the executive seeks to protect the nation from foreign dangers, subordinating foreign policy to national interests and designing national policy by his own perception of national vulnerabilities. While not at first even asserting that it constituted a ban, and describing it as a purely temporary action, the lack of any reason for lifting the ban made it a major reorientation not only of American foreign policy, but of international relations.

The draconian nature of a ban on citizens of Muslim-majority countries and refugees was hard to imagine, let alone implement, as it appeared a de facto coup and foreign policy change as much as an illustration of executive strength. The decree issued late Friday night with urgency, restricting visas or processing refugees. In arguing that the ban was part of “not allowing” the threat of “radical Islam” to “take root in our country” lest it be “put in peril” the nation. Issuing the Ban sewed fears of an impending threat repeatedly on social media, conjuring “people who want to destroy our country”–as a rationale for banning the entry of both refugees and foreign visitors who might be suggested to have ties to the national danger he has identified with Islam. For the Ban perpetuated a fantasy of ensuring sealed borders has created a dangerously deceptive mental map of national purification, as if freeing the nation from danger: the Ban was promoted by mapping dangers that lie outside the country, indeed, as if intentionally to distract audiences from those that lie within. But it is also to define the clearest challenges to traditional authority and order from without, and to locate those challenges in states most easily able to tie to Islam.

Trump had regularly evoked a frequent opposition between us and them in his campaign speeches that are echoed in his appeal for voters’ trust in his person, but the Friday night executive order placed such heightened restrictions on entering the country that evoke his warnings of the dangers of accepting refugees to the nation. Repeated allusions to the security threat posed by the imminent arrival of “potential terrorists,” “many very bad and dangerous people,” or just “certain people” were purposefully vague–as if to naturalize a division between faiths and worldly civilizations, barely trying to conceal the implied target of the ban, so that it almost never need to be mapped at all to be explained. For as the first advertisements Trump used to call attention to his candidacy by suggesting such a “temporary ban”–of unknown duration–seem to have derived from a need to make good on the promises of his campaign that a new border policy could provide security that Trump seemed to suggest was absent or not provided in current immigration policy.

CNN/FOX

Both CNN and FOX TV used the above news map to embody the ways that the executive order confronted the threat that America suddenly seemed to face. The emergency conditions Trump argued rationalized the executive order were not at all specific, but suggested an amorphous danger whose contours were not able to be mapped–as if the ban provided the only certainty to prevent national enemies from entering our territory. The map was not only a map of nations of Muslim-majority populations, but was itself a trigger of a larger map of fear. Trump’s repeated evocation of unspecified threats on his personal social media echoed candidate Trump’s urging for the need for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” in the wake of the San Bernardino tragedy in December 2, 2015–a demand conjuring a military or police “lockdown“–which launched an implicit attack on the executive of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton during the Presidential campaign, and which the executive order seems issued to make good upon, irrespective of the law or civil liberties.

President Trump at first insisted the executive order was only named a Muslim Ban only by the “media,” as he misleadingly claimed with rancor, indignation and righteousness it was in fact not a ban at all–“Everyone is calling it a ban! Call it what you want!“–it was. And by February 4, Trump tweeted with pride middle eastern countries “agree with the ban” as a selective closing of national borders to foreign nationals. Trump’s animus to Islam was long replayed on the campaign trail and in his statements on the twitterverse–Trump not directed attention to it as the source of the violence of the San Bernardino shooting, long before Stephen K. Bannon openly joined Trump’s inner circle–but about when Bannon bragged he was designing Trump’s campaign platform, and may well have planted the deeply oppositional relation to Islam both in Trump’s campaign and as a quite distorted but apparently unshakeable principle of his image of the purpose and prerogatives of the executive office of the President.

The retrospective explanations for the need to protect America from dangers unknown concealed the ban’s quite arbitrary nature: the hastily issued executive order seemed to respond to a state of emergency outside of a functioning civil society, creating a map of imminent dangers to the United States from whole cloth that only the “extreme vetting” that he promised to enact would forestall–and that any stay in the ban would compromise. Before playing a round of golf at Trump International on February 4, the seventy-year old so-called President identified the proposed Ban with the nation’s integrity and safety, insisting that “death and destruction” were the only alternatives to its re-instatement. At the same time as unleashing a rash of executive orders, Trump has taken to twitter as a form of constant dialogue with the nation and himself, to suggest the only further destabilization of our nation’s safety and its place in the world.

Recent allegations of the increased danger that the Immigration Ban created for the American military and the nation by intelligence experts reverse this picture, even as Trump suggests that actual threats are just “not being reported”–in an attempt to discredit news agencies by ominously suggesting that the media “doesn’t want to report it.” Such claims fanned the fear the Immigration Ban created by Trump’s executive order intentionally provokes. For when it was suddenly unleashed on the country on the evening of Friday, January 27, 2017, indefinitely banning the entry into the United States of Syrian refugees “by the authority invested in me by the Constitution and laws of the United States of America,” the executive order not only departed radically from those laws, and from the U.S. Constitution. But they also escalate the fear to a level of abstraction, as in targeting seven nations, the executive order serves to distract audiences from the actual people that the Ban affects–and the possible targets which a Trump administration seeks to direct increased scrutiny that intersects closely with nations with Islamic populations.

The extreme secrecy with which the draft order was framed should raise eyebrows, as its lack of vetting and the constitution of such a tightly knit circle that seemed to see itself as the US government. For in ways that echoed the of urgency Trump used on the campaign trail in December, 2015 when he explained the “shutdown,” the hastily written executive order–thankfully stayed–set its focus on seven nations. The decision was deceptively rationalized as a temporary ban on nations, continuous with a stay in processing refugees from the same countries. Trump’s hastily issued ban on countries he identified with terrorism and his disdain for their population–“we don’t want them here!” “All 1.6 billion Muslims?” “I mean a lot of them!“–were so decidedly un-Presidential to violate the Constitution, a federal judge since suggested. The seven states combines twelve countries deemed “safe havens” for terrorist organizations with three–Iraq, Sudan, and Syria-identified as “state sponsors” of terrorist activities, but omits many countries where terror networks actually operate.

The tacit map locating the prime threats to our nation outside our shores make the selection unjustified as its intersection with refugee flows make it irresponsible and capricious. But the executive order also seemed an attempt to remap the power of the executive office itself, by creating what is tantamount to an alt-Reality for the alt-Right, designed in the Oval Office for the world to witness as its effects spread and play out across the world: while there is no actual policy decision evident here, it is a gesture that placates the need for reacting to fears of attack, and perpetuates the lie Muslims breed on hatred for the United States, and “engage in acts of bigotry or hatred“–far better describing the order’s own tone than offering an accurate characterization of its actual targets.

The “ban” declared on obtaining visas or welcoming all refugees to the nation, although formally limited to a period of weeks, created a clear opposition between Muslims and Americans–them an us–specially corrosive to our sense of a nation, and how our nation regarded. While widely varying numbers are provided both by the Trump administration and the State Department about how many will be most affected by the hastily ordered assertion blocking the granting of visas that seems more a performative assertion than a basis for protecting our borders, but has real consequences that will be difficult to map for some time. For the executive order effectively invested the President with powers to define national borders and, perhaps more disquietingly, unwarrantedly but ever so purposefully escalate existing fears.

As the order is broadcasts a new world-view on media and television, it solidified a geopolitical division between us and them, placing Islam stands in a perpetual state of war with the West. While the ban contains several puzzling mismappings and omissions–including the fact that the prime site of the Wahabi sect of Islam, the greatest exponent of terrorism, and one that is funded by the Saudi state is entirely absent from the map, underscoring its actual arbitrary classification of terrorist threats that the nation faces. Although Trump claimed it was “interesting that certain Middle East nations” supported the ban, the only states whose public positions might be taken as expressing support–the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates–are deeply non-democratic lAmerican allies, eager to cultivate ties with Trump. Although the immigration ban by no means addressed Muslim populations world-wide, it it’s goal were not to name enemies and site of danger on which to focus our attention as threats to the United States–

–the seven nations identified as terrorist safe havens or state sponsors of terrorism were designated as the primary sites of threats to our nation–a theme raised repeatedly in the campaign. The tightly worded ban seemed the feared conclusion of a series of pronouncements of the dangers that Islam posed to the United States.

Trump’s dramatic response to the San Bernardino tragedy in early December 2015 of securing the national borders is often cited as a precedent for the ban, if not a justification of it, to an extent that Muslim communities in San Bernardino rightly object. The way that the ban came to be both explained and rationalized in the form of a map, as if to process and lend coherence to what the effects of this order from on high actually were–and to celebrate its decisiveness–raises questions of the power of maps in online communities. The ban of immigration from seven ‘Muslim-majority nations’ incriminated their residents for ties to terrorist organizations with no proof, included states from which large numbers of refugees had already arrived in the United States–although the ban will cause that number to drop by half, and exclude all Syrian refugees.

The large number of refugees from these Muslim-majority nations overlaps not only with many nations that are overwhelmed by untold refugees: they are also largely victims of American attacks or government overthrows, or are currently under attack from American troops. A number of nations are subject to recent bombings–unlike those that were deemed to be allied with Trump’s businesses–and to his vision of America’s security.

Trump’s executive order on immigration lacked any coherence, or a clear or systematic explanation. It was asserted outright with a forcefulness, typical of Trump’s statements, that belied its lack of clarity, but demanded a map–and a map that went beyond the protection of national boundaries. What it lacked in explanation was made up for by the forcefulness of his interest in protecting American interests–a rhetorical force that echoed not only his bizarre declaration that the nation’s safety demanded “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on” in light of the tragedy of San Bernardino that was perpetrated by American citizens–it however seemed to translate the seeds of panic to a map, as if to give an only illusory stability to the fears it nourished. If the immigration ban caused immediate confusion by prohibiting entry to the United States of all citizens of seven Muslim-majority states and suspending of entrance of all refugees, the odd patriotism within which Trump steeped his actions bear the prints of Trump’s chief strategist, Steve Bannon, as several publications have noted. More than being a stunt of public relations using geographical categories to demonize a group of citizens en masse to dispel the very imagined dangers it conjures at one stroke, it was a performative illustration of Trump’s newfound Presidential powers, and a powerful remapping of where the enemies of American freedom lay.

The order asserted executive power if not supremacy. President Trump angrily dismissed objections after Acting Attorney General Sally Yates counseled questions about its legality or ethics, when he described her resistance to defend the ban in court as constituting an act of “betrayal” in personal terms. For Trump, her carefully weighted decision constituted an act of insubordination. Trump’s statement revealed his tendency to divide people into those “for him” or “against him,” he seems to have used the distinction between “friend” and “enemy” in ways that embody a weltanschauung of the ethics of a state: for the order served to cognitively re-orient the United States in the external world, and define ethical relations of the nation to the world. Far beyond changing who held the office of Attorney General, whose office Trump treated less as having the responsibility to interpret and execute laws than as if tasked with defending the executive judgements in extraordinary times–and as a question of the limits of executive authority. Despite questioning of the legality of the ban, Trump has only re-asserted its constitutional authority–and suggested his willingness to re-write the Ban, despite strong questions about how its intent could ever be constitutional.

For the executive order affirmed the executive prerogative to close the nation’s borders at will, distinguishing who would enter the country at any time and defining the nation’s relation to the rest of the world. It echoed a precedent of the Bush administration, by deploying a friend/enemy distinction. For if hastily framed, Trump’s executive order quite terrifyingly rehabilitated the most odious classic critique and rebuke of a Liberal tradition, exhumed from oblivion of political theory during George W. Bush’s Presidency, deeply rooted in the Catholicism of its primary intellectual exponent, the prolific Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt, who had been quick to defend the Führer as “supreme judge” and sole custodian of the law, defending the legality of notions of “state self-defense” that Hitler claimed as his own in the very speeches Trump kept by his bedside which his wife Ivana claimed he often read. The exhumation of an almost forgotten ideology of political sovereignty is not only an abstraction, but served to constitute a new constitution of Empire–or imperium, as per the political scientist Ronnie D. Lipschutz–as Schmitt offered juridically terms to sanction the ability of an executive to move in a blatantly extraconstitutional form when dire states of circumstances demanded to define his actions on a global stage. Indeed, Hitler’s rhetorical patterns of repeatedly calling attention to enemies of the state and the necessity to take action against them were often emulated in Trump’s campaign: the disguising of xenophobia as foreign policy is not only arrogant, but reflects Trump’s all too familiar Bannon-like bullying tone.

Trump’s hastily issued if not impulsive executive order affirms the government’s ability to close the nation’s borders at will, in an explicilty extraconstitutional manner to distinguish who would enter the country–a travel ban since struck down, and that a federal appeals court refused to restore as the Trump administration had sought. But the mapping of ban was not only a way to explain its scope, but come to terms with its arbitrary nature. For it was widely apparent that the below map of countries impacted by the ban mishaps the origins of terrorist dangers to the United States, and openly omits the country that spent more than $100 billion have been spent to export the sect of fanatical Wahhabism rooted in the KSA to various much poorer Muslim nations. Few questioned the logic of excluding Saudi Arabia, where Wahabism was long promulgated in its universities and mosques. But its omission, and the confusion of the apparent mipmapping of terror, caused the spread of numerous maps to try to sort out the nature of the newly enacted restrictions–

–which many suggested might logically be expanded to much of the globe if followed to what seemed its logical scope–if its goal was not to sew alarm by mapping sites of danger, and create the quite misleading illusion that the United States was not endangered by any domestic agents who did not in fact arrive from overseas, or what the nature of the terror threat that the country faces might in fact look like or be. Rather than focus on individual agency, the Ban inconveniences and targets a huge range of countries with a large presence already in the United States–and many of whom already have immigrant or non-immigrant visas.