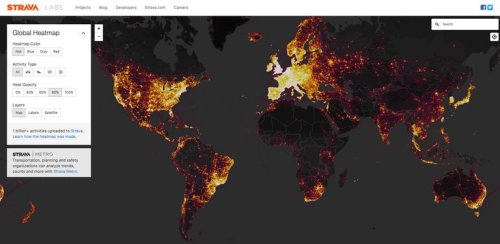

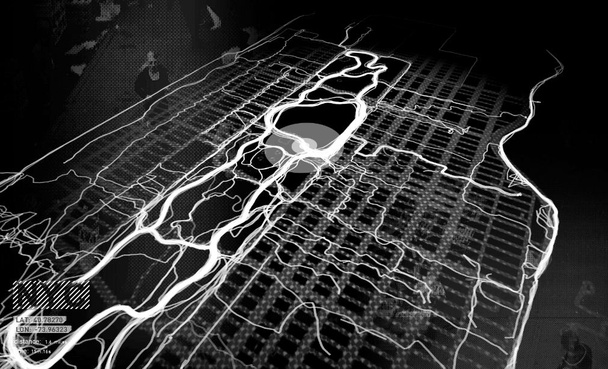

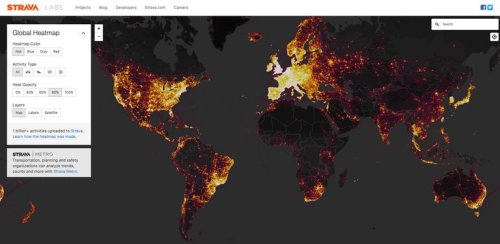

Was it only a coincidence that on the eve President Donald Trump boasted in his State of the Union address of an era “we no longer tell our enemies our plans” that the release of a live global heatmap pinpointed the location of U.S. military installations? The release by Strava Labs of a spectacular heatmap that celebrated the routes where folks exercise worldwide suggested the flows of itineraries of physical exercise by running, biking, or skiing in stunning lines to reflect increased intensity, that appeared as if engraved on a dark OSM base map. Indeed, the open nature of the data on military positions offered to any viewer of the heatmap seems as pernicious as culling of internet use long engaged in by the NSA, but for the state–as well as for the safety of soldiers who share their location, or fail to use security settings, as they exercise while completing military service abroad. Is this approaching a new level not only of broadcasting plans to an enemy, but failing to protect military positions in internationally sensitive zones?

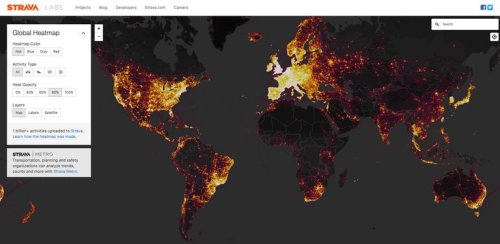

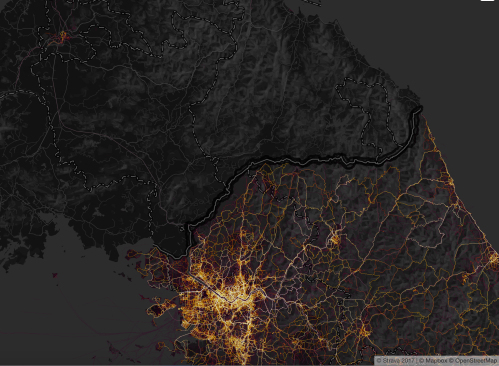

While the map had been around for several years, its detailed update was so much more comprehensive than the 2015 version included–and was released in a time when internet observers scrutinize data visualizations. The updated heatmap was a big deal for how it illuminated the world in a ways that few had seen, both in its own architecture of a spectacular network of athletes that reflected its expanded use, and the huge data included in aggregated routes for training, but illuminating clear divides between its users; but it gained even more attention foregrounding the presence of isolated groups of athletic performance abroad with an eery precision and legibility that quickly raised concerns reminiscent of the scale of unwanted intruding or monitoring of physical actives, even in an app that based its appeal in the data density of tracking it provided. While promising individual privacy or anonymity, the benefits promised by the fitness app seemed almost a runaround of the appeal of PGP, Tor, and Privacy Badger that promised a degree of privacy by encrypting data from online trackers and privacy self-defense; rather than ensure the anonymization of the internet connections, however, the platform posted patterns of use whose legibility did not violate individual privacy, so much as state secrets. Indeed, the surprising effects of how the Strava app made individuals suddenly legible so that they popped out of darker regions was perhaps the most striking finding of the global heatmap, as it illuminated stark discontinuities.

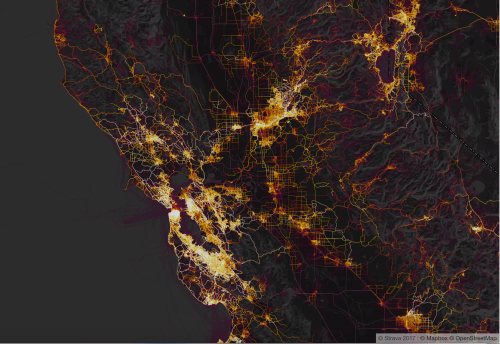

The newly and vastly amplified dataset included zoom functions of much greater specificity: so richly detailed Strava was charged with betraying once secret locations of U.S. military worldwide, even if unknowingly, and creating a data vulnerability for the nation the would have global effects. The heatmap made stunningly visible rasterized images of the aggregate activity of those sharing their locations that it gained unwanted degree of publicity months after it went live in November, 2017, for revealing the actual location and global military presence of American soldiers tracking their exercise and sharing geodata–including American and European soldiers stationed in the Middle East and Africa, and even in South Korea. Although the California-based fitness app rendered space that seemed to celebrate the extent and intensity of physical exercise in encomiastic ways, as if the app succeeded in motivating invigorating exploration of space, and tracking one’s activity that guaranteed anonymity by blending data of its users in brightly lit zones, as for the Bay Area–

–the image that had clear implications of announcing its near-global adoption registered in the more isolated circumstances that many members of the American military increasingly find themselves. The data set that Strava celebrated in November, 2017 as “beautiful data” on the athletic playgrounds of the world took an unexpected turn within months, as Strava came to remind all military users to opt out of sharing their geodata on the zoomable global heatmap, that aggregated shared geodata, lest secret locations of a global American military presence that extended to the Middle East and Africa be inadvertently revealed. Whereas the California fitness app wanted to celebrate its global presence, the map revealed the spread of secret bases of the U.S. military in a globalized world. The map of all users sharing geodata with the app were not intended to be personalized, but the global heatmap showed bright spots of soldiers stationed in several war zones.

The narrative in which the map was seen changed, in other words, as it became not a data dump of athletic performance across the world, that was able to measure and celebrated individual endurance, but a narrative of hidden military and intelligence locations, tagging CIA operatives and overseas advisors by indelibly illuminating their exercise routes in a field of war in ways that seemed to foretell the end of military secrets in a world of widespread data-sharing. And Strava Labs for their part probably didn’t exactly help the problem when they took time to assure the public that they indeed “take the safety of our community seriously and are committed to work with military and governmental authorities to correct any sensitive areas that appear” in the web-maps,” as if to assure audiences they privileged the public interest and public safety of their users. (But as much as addressing public safety in terms of operational security, Strava’s public statements were limited to caring for the community of users of the app, more than actual states. The disjunction reveals very much: when Strava labs saw their “users” or customers as the prime audience to which they were faithful, they indeed suggested that they held an obligation to users outside of loyalty to any nation-state, and indeed celebrated the geographical distribution of their own community across national frontiers.) Indeed, the app’s heatmap disrespected national frontiers, by suggesting an alternate space of exercise that was believed and treated as it had nothing political in it.

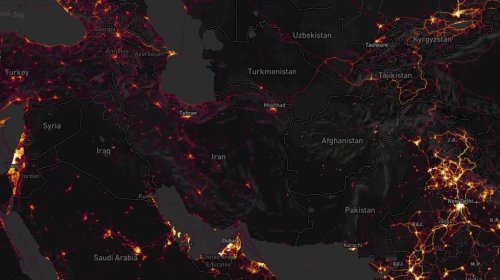

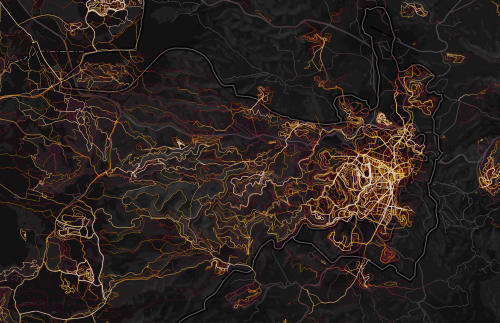

In contrast, the landscape that American President Donald Trump presented in his first chest-thumping first State of the Union returned to the restoration of American security seemed incredibly to deny the consequences of recent availability of military geodata and indeed military base locations, in announcing that in his watch, we “no longer tell . our enemies our plans. For whereas President Trump boasted the return to an era of national security and guarded military secrets, the app broadcast a pinpoint record of the global dispersion of American troops, military consultants, and CIA “black” sites and annexes. Indeed, for all the vaunted expansion of the U.S. military budget, the increased vulnerability of special operations forces has been something that the United States has poorly prepared for, although the release of the heat map prompted Gen. Jim Mattis to undertake a review of all use of social media devices within the military, so shocked was the news of the ability to plot geographical location by the exercise app. If the activities tracked and monitored in the hugely popular fitness app suggested a world taking better care for their patterns of exercise, it revealed scary patterns as a proxy to chart American presence that map the recent global expansion of the United States military in the beauty of its global picture across incandescently illuminated streams–

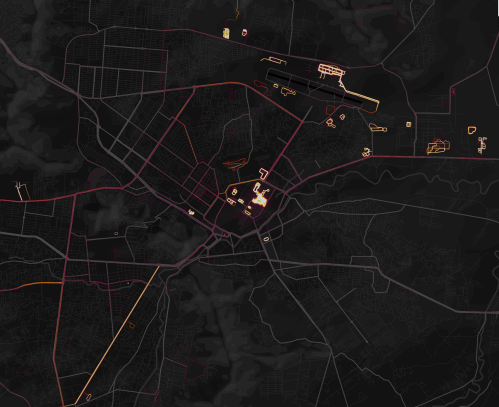

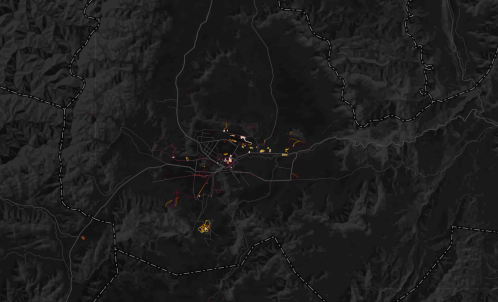

–as when one zoomed down to those running in Kabul, and geolocated the movement in ways that betrayed military footprint from intelligence personnel to foreign operatives to contractors overseas. The data harvested on its platform appears to endanger American national security–and offers new ways to combine with information culled from social media–as it seems to pinpoint the bases around which military take their daily runs.

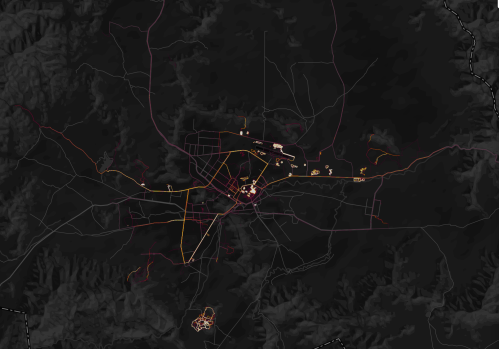

Strava heatmap, Kabul

Strava heatmap, Kabul

The recognition of the scale of personal tracking by soldiers sharing data on exercise apps grew as one exploited the heatmap’s scalability, and examined areas in which few locals were using it–or had access to the First World problem of registering how many miles one ran. While the data was not only sourced from Americans, the anonymity of the aggregate map–which can be viewed in multiple shades–provided an image of ghostly presence that seemed particularly apt to describe concerns of security and suggest an aura of revealing secret knowledge. The cool factor of the Strava map lit up the hidden knowledge that echoed the longstanding surveillance of the communication records of Americans in the bulk data collection that the Patriot Act allowed, although now the dragnet on data use was being done by private enterprise, suggesting an odd public-private sharing of technology, as what had been viewed as a domestic market suddenly gained new uses on an international front. The poor data security of U.S. forces abroad reminded us that we are by no means the only actor collecting bulk data, but also the scale of digital dust that we all create as we entrust information about our geographical locations to companies even when they promote the value of doing so to be salutary.

Multiple accusatory narratives quickly spun about whether the release of the new global heatmap by Strava Labs constituted a breach in national security. The soundbite from the State of the Union proclaiming a “new era” described changed conditions by referencing Gen. Michael Flynn’s charge, first raised during the 2016 Presidential campaign on national television news, that the United States had sadly become “the best enemies in the world” during the Obama years, as he attacked the government of which he had been part for being itself complicit in how “our enemies love when we telegraph what we’re doing” by not maintaining secrecy in our military plans. Flynn’s assertion became something of a meme in the campaign trail. And President Trump sought to reference the fear of such changes of a past undermining national authority abroad when he claimed to bring closure to lax security, choosing to message that the loopholes that existed were now closed, and respect had been achieved. The fictionalized imaginary landscape seemed to distract America from danger or unemployment in celebrating its arrival in a better economic place. The message seemed as imaginary as the landscape of an employed America, which had arrived in a better economic and place.

General Flynn’s metaphor of telegraphing was even then quaintly outdated, as if from a different media world. But the allegation that had become a meme on alt right social media during the campaign to discredit military competence, gaining new traction as data security became increasingly a subject of national and international news. Since President, despite having quickly issued one of executive orders that he has been so fond of signing on cybersecurity, Trump has in fact been openly criticized for a lack of vision or of leadership in addressing national vulnerabilities in cybersecurity. As President, Trump has preferred to pay lip service in the executive order, by far his preferred medium of public communication, to the growing frustration of a number of cybersecurity advisors who resigned before clarifying best practices of grid security. Broad sharing of geodata by military and intelligence raised red flags of security compromises; it would, perhaps, be better raise a clarion call about our unending readiness to aggregate and be aggregated, and the unforeseen risks of sharing data.

The patterns of tracking exercise–biking, running, swimming, windsurfing–created striking pictures in aggregate, reflecting the collective comparisons of routes and itineraries, and showing a terrain vibrant with activity. But while the app did not specialize in tracking individual performance or local movements, the new context of many apps transformed foreign counties where military travelled to sites where their data sharing stood out. The sense of accessing the platform was so second nature to American soldiers moved across space, in fact, ignorant of the platform on which it was aggregated and its effects–or the audiences before who it was broadcast and displayed. The ability to detect bright spots of athletic engagement around American bases, military camps, and CIA outposts suggested an unwanted form of data-sharing, RT television newscasters proclaimed with undisguised pleasure at the ease with which soldiers could be observed in different locations across the Middle East, from Saudi Arabia to Afghanistan, to Pakistan, and crowed that Americans are so unwary about being surveilled so as to provide evidence willingly of their own global footprint’s size.

It’s striking that government secrecy has become a public hallmark of the Trump administration. But if Trump wanted to inaugurate the start of a fictional landscape of securing state secrets in his first State of the Union address, his words were pronounced with no acknowledgement of the release of the heatmap and the concerns of leaking security operations. The map that Strava labs designed to celebrate the global extension of a triumphal image of the expansion of exercise in a triumphal image appeared in new guise as the latest example of breached military security secrets–suddenly made apparent at high resolution when one zoomed in at greater scale to Syria, Somalia, Niger, or Afghanistan, and even seem to be able to track the local movement of troops in active areas of war, and not only identify those bases, airfields, and secret annexes, but map their outlines that corresponded to the laps that soldiers seem to have run regularly around their perimeter while sharing their geodata publicly, or with the app. While the app was designed to broadcast one’s personal best, as well as log one’s heart rate, sleep patterns, and performance (personal data which remained private), it collated in aggregate the patterns of activity across national borders.

For its part, Strava had only boasted it could “create the ultimate map of athlete playgrounds” by rendering “Strava’s global network of athletes” in a stunning heatmap from directly uploaded data. If there was a sense that the “visualization of Strava’s global network of athletes” described a self-selected community, the beauty of the data set created from 13 trillion data points provided a new sense of exercise space, as if it sketched a record in aggregate of individual endurance, or a collective rendering of folks achieving personal bests. But the illuminated “maps” of the global network of those exercising and the distribution of US military bases and sites of secret involvement raises complex issues of data-sharing, and the shock at the intersection of leisure space and military secrets–somewhat akin to the stern warning military commanders issued to years ago about using Pokemon Go! in restricted areas of military bases, mapping a comprehensive global map of military over-extension is an odd artifact of globalization. And it was odd to see RT seize on this issue, as a way of describing the presence of the actors they id’d as “Uncle Sam” to suggest how zooming in on the global map revealed the reach of the United States in Afghanistan or Syria, as if playing a computerized game to see where clusters of forces might be illuminated, as if to exploit fears of revealing military secrets through geolocated data.

The story was pitched on RT suggested a market-driven surveillance network of which the Americans were themselves the dupes. In its own spin on the story, RT reported of the leaks with glee, for rather than arriving from hackers, or Russian-sponsored hacking groups, military security was compromised by the very tracking devices, it was argued, that soldiers, military intelligence, and CIA officers wore.

By imposing outlines of national maps on the dynamic rasters of the web map that Strava released, the position of military forces or advisors indeed seemed able to be roughly revealed as military secrets by zooming into locations, much as RT announcers asserted, as if the “bracelets” of fitbits provided tools to geolocate soldiers as if they were manacles, reminiscent of the ankle bracelets given to many parolees, sex offenders, or prisoners, by using a GPS tracking system to monitor released inmates all the better to monitor their acitivities, in a practice that has only grown in response to overcrowding conditions in many federal and state prisons–GPS tracking systems were billed as able to save prisons up to $9,500 per inmate, or up to $25 a day; but rather than provide tools to surveil non-violent offenders, the effective monitoring of military bases and what seem CIA field stations provided a multiple security vulnerabilities of unprecedented scale.

But the real story may have been how so much data was available not only for state eyes, but for a broader public: in an age where surveillance by the state is extending farther than ever before, and when we need, in the words of Laura Poitras, “a practical and metaphorical road map for navigating the post-9/11 landscape,” the maps of Strava have shifted the landscape of surveillance far from the state, and deflected it onto the internet. For the far greater geographical precision and detail of a diverse user group may prefigure the future of data sharing–and the increased vulnerabilities that it creates. The live data map broadcast not only an image of global divides, but of the striking patterns of the aggregation of geodata that reminded us of the pressing problem of data vulnerability in the military’s extended network of secret military bases and dark sites. Indeed, when a student at the Australian National University in Canberra, Nathan Russer, first noted that the Strata search engine created an Op-Sec catastrophe for leaking locations of US military patrols and bases, his observations unleashed a storm of pattern analysis and fears of compromised national security. It indeed seems that the vaunted agility that allowed American forces to deploy in much of the world could now be readily observed, as we zoom into specific sites of potential military involvement to uncover the presence of Americans and assess the degree of involvement in different sites, as well as the motion through individual sites of conflict. The spectral map that results suggests something quite close to surveillance–at time, one can scrape the place of individual users form the app’s web map–but that is dislodged from the state.

The notion of a private outsourcing of data surveillance to the public sphere is hardly new. One can think, immediately, of Facebook’s algorithms or personal data-harvesting or those of search engines. Although the U.S. Department of Defense has urged all active military abroad to limit their active presence in online social media, no matter where they are stationed, the news reminded us yet again of an increased intersection between political space and social media, even if this time the intersection seems more shaped like a Moebius strip. The divisions within a global geographic visualization of Strava’s users reminded one of a usage landscape that suggested a striking degree of continuity with the Cold War–with an expanded iron curtain, save in scattered metropoles–whose stark spatial division reminded us of the different sort of lifestyles that public posts of athletic performance reveals. As much as showing a greater openness, the heat map suggests a far greater willingness of posting on social media use: the intersection suggests a different familiarity with space, and a proprietary value to the internet.’

Strava Labs

Strava Labs

Indeed, in only a few months to notice how American soldiers’ presence in coalition military sites suddenly popped out in the darker spaces of the Syrian Civil War, where different theaters of action of coalition forces that include American soldiers are revealed, and panning back to other theaters can indeed revealed the global presence of U.S. military and intelligence. Against a dark field, the erasure of any sense of national frontiers in the Strata labs data map suggests the permeability of much of the world not only by interactive technologies but by the isolated groups of soldiers who deal with the stress of deployment by bike rides and runs while they are stationed in Afghanistan.

Although the fitness app saw its aggregation as registering geodata in the relatively apolitical space of physical exercise, fears of political and national security repercussions ran pretty high. Indeed, the tracking of running laps, cycling, and daily exercise routines revealed U.S. military bases in Syria so clearly that it proved a basis to locate and orient oneself to an archipelago of U.S. military activity abroad in the global heat map, and lit up American presence in Mosul, Tanff, north of Bagdad and around Raqqa, providing a historical map able to pinpoint airfields, outposts, and secret stations in the war against the Islamic State. Security analysts like Tobias Schneider argued they helped track the movements and locations of troops and even extract information on individual soldiers. In place of an image of the global contagion of tracking exercise, the patterns of performance provided a way to look at the micro-climates of exercise on a scaling that were not otherwise evident in the arcs of the impressive global heatmap.

Sissela Bok classically noted the ways that secrecy and privacy overlap and are linked in some collective groups, as the military, but the absence of privacy or secrecy on much of the Strava Labs heatmap raised questions of the increasing difficulties to maintain a sense of secrecy or privacy in an age of geographically growing war. In an age when more and more are living under surveillance, and indeed when the surveillance of subjects has only begun to gain attention as a fact of life, the fear of broadcasting an effective surveillance of exercising soldiers seems particularly ironic–or careless. The practices of secrecy were more than lax. For the United States military has in fact, quite vigorously promoted Fitbit flex trackers among pilot programs at U.S. bases to lose calories, and provided devices that measure steps walked, calories burned, and health sleep as part of its Performance Triad; Fitbit trackers were provided as part of a pilot fitness program from 2013 with few issues raised about security, and placing restrictions on American soldiers’ use of mobile phones, peripherals, or wearable technologies would limit military volunteers. (The Pentagon has in all distributed 2,500 Fitbits as part of its anti-obesity program, in more flexible wearable form, without thinking of the information that they broadcast.) Yet soon after the map appeared, folks noted on Twitter with irony that “Someone forgot to turn off their Fitbit,” and it became a refrain on social media by late January, as the image that tracked American military outposts not only in Kabul, but in the Sahel, Somalia, Syria and Niger all popped out of a global map–embodying the very outlines of the camps around which military run. ‘

Although the U.S. National Counterintelligence and Security Center informed the intelligence community of dangers of being tagged by “social media postings,” the imagined privacy of exercising soldiers is far less closely monitored than should be the case–resulting in a lack of clear vigilance about publishing Strava data.

Kabul, Afghanistan, in Strava Labs global heatmap

Kabul, Afghanistan, in Strava Labs global heatmap

The heat map so strongly lluminated itineraries users ran, biked, or skied, tracked in incandescently illuminated streams, and even zoom in on specific locations, where they stand out from considerably darker zones of low use of the app, that some national security officials wanted the app to take time to take the maps offline so that they could be scrubbed; worries grew that one could even to scrape the itineraries of individual soldiers who exercise on military service in the heatmaps.

But the two fold ways of reading of the map’s surface suggest that their contents were difficult to free. The same map celebrating the app’s global use revealed deep discrepancies between the brightly illuminated areas of high-use and data input and its dark zones. Data mapped on Strava’s website also seems to enable one to id the soldiers using the Strava app with far greater certainty than foreign governments or non-state actors had before, in ways that would create multiple potentially embarrassing problems of delicate foreign relations. While in part the fear may have derived from the hugeness of the dataset, the fear of being compromised by data raised an increased sense of emergency of a security being risked, and fears of national vulnerability. Partly this was because of the huge scale of geospatial data. The updated version of the heatmap issued by Strava Labs illuminated the world in a way that few had seen, and not only because of its greater specificity: Strava had doubled its resolution, rasterizing all activity and data directly uploaded, and optimizing rasters to ensure a far richer and more beautiful visualization, along glowing lines to reflect intensity of use that looked as if they were in fact vectors. It made its data points quite beautiful, stretching them into bright lines, eliminating noise and static to create a super smooth image that almost seems to update the Jane Jacobs’ notions of public space and its common access–and the definition of spaces for exercise.

To some extent, the highlighting that the app did of common routes of exercise seem to mirrored the metric of walkability, the measurement of active transportation forms like walking and biking and stood as a surrogate for environmental quality. The fitness map improved on the walkscore or its cosmopolitan variants, by involving its users to create a new map of exercising space. The abilities to foreground individual and collective athletic performance in a readily accessible map provided what must be admitted is a pretty privileged view of the world; but the self-mapped community it revealed gained a new context just two months after it went live, as the map drew attention to the patterns it revealed of using an app to track one’s activities, as much as register work-out trails.

San Francisco in Strava Labs Heatmap

San Francisco in Strava Labs Heatmap

The new map attracted attention not only for the fitness crowd, a self-selecting demographic, in short, but as an interesting extension of the beauty and the huge amount of datasets it uploaded and digested in a highly legible form: indeed the legibility of the data that was able to be regularly updated online suggested a new form of consensual surveillance. The data-rich expansion of what was the first update to the global heat map of users that Strava Labs issued since 2015 encoded over six time more data, and promised a degree of precision that was never even imagined before, notably including correction for GPS distortions and possibilities of new privacy settings, in ways that amplified its ability to be seen as a tracking device most notably in those areas where the aggregate of Strava users was not so dense, first of all those military sites where American military and operatives were stationed and perhaps secretly engaged, but gave little thought to the day sharing app installed on their Fitbits or iPhones, and may even have seen the data-sharing function as a source of comfort of belonging to a larger exercise community.

Rather than suggesting the expanse of outdoors exploration, the bulk of media attention turned to far less beautiful data, showing what can only be called increasingly restrictive courses around base-camps and military stations. Strava Labs had, for their part, respected clear individual privacy and set privacy rules, which they also requested users follow. Indeed, despite the alarms raised both about the huge amount of geodata made available on the heatmap, it bears mentioning that military seem to have faced minimal oversight from officers who undoubtedly wanted folks to be comfortable and well-oriented while stationed overseas. Strava was only interested in mapping aggregates, in a benevolent sort of self-monitoring and tracking that allowed users to keep a record of their outdoor exercises, track their heart rates, record their times, and note their personal bests. But did the ways that the heatmap embody a world of exercise unwittingly reveal sensitive information that could be readily weaponized?

Does the heatmap indeed change the picture of global security? It at least reveals a new image of globalization, where the private California-based app the offers global athletes its services intersects in stunning ways with the global military presence that the United States is increasingly challenged to manage. Whereas Trump sought to celebrate how the first year of his Presidency had already changed America, Strava, for its part, was only eager to celebrate the expansion of tracking athletic exercise on a global scale. The heat map was an up-beat triumphal image of the widespread popularity of the fitness app, boasting it could “create the ultimate map of athlete playgrounds” via “Strava’s global network of athletes,” using the rhetoric of global expansion to boost a message of the fitness of its users. But for a President who has only offered quite limited response to the cybersecurity threats, and the dangers of compromises to data in private sector industries or openly shared information, the geodata reveal a collective picture of global military involvement of the United States that undercut claims in the State of the Union address for restoring responsibility by safeguarding privileged military intel, undermining the classified nature of military data on an actual Universal Transverse Mercator grid that might fall into the hands of enemies is actually displayed to them, directly uploading position in real time renderings. The registering of the lat/long coordinates all data points are translated into Web Mercator Tile coordinates at tiles that render a global tessellation of 256 by 256 pixels, explained Strava engineer Drew Robb, rasterizing some 13 trillion pixels in toto, whose zoom levels allow pixel-perfect paths at an amazing resolution of two meters, drawing a line trillions of times to connect GPS data points in clean rasterized paths in an up-to-date record of individual routes.

While not holding personal information, and allowing geodata to be withheld, the illuminated routes disclosed patterns and hence locations the US military had long sought to conceal, but which the app allowed to pop out of the screen in ways that could not but read as possible targets for attack–as well as potentially highly embarrassing revelations of where CIA annexes and military bases–none of which are openly identified on the OSM platform, of course–can be easily inferred to lie. The map raises questions of not only what beautiful data is, perhaps,–but how much beauty lies in the eye of the beholder. The popular fitness app was rightly proud of the truly “beautiful dataset”–a visualization Strava boasted to be “the largest, richest and most beautiful dataset of its kind”–including six times the aggregate data it had previously displayed than the version of 2015, in a measure of the exponential growth of its users over a small period of time. The global space of 13 trillion data points was very much an artifact of globalization–despite some geographical limits–embodied by a map that celebrated its use worldwide tracking. Yet the beautiful data intersected in uncomfortable ways with the global stationing of American troops, most of whose constrained routes of exercising were displayed in blacked out war zones in nations like Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Djibouti, and elsewhere, the dark areas defined by far lower use of the app, and as such registers a deep divide in the world, once one examines it less as an individual form of sharing data than in terms of the broader patterns revealed in the global heatmap.

1 The webmap had seem to have gained an unexpected weaponized status as members in the military services turn it on when they exercise, where they are the only folks around who use it while they exercise. The beauty of the data set created from 13 trillion data points shifted from mapping a global playground to mapping secret military sites in the global warplace. In a double-edged trick of topographical rendering, the Strava heatmap not only showcased the intensity of route use, of course, but its relative absence–evident in the deep unlit spaces in much of north and central Africa, the Australian interior, and of course much of China, Korea, and central Asia, defining an alternative mode of imagining global illumination through connectivity and the cultures of wifi, as much as upload speeds, and one which is able to zoom to within a few meters of accuracy. Was this a dataset waiting for weaponization, or a vulnerability that is almost baked into the online world?

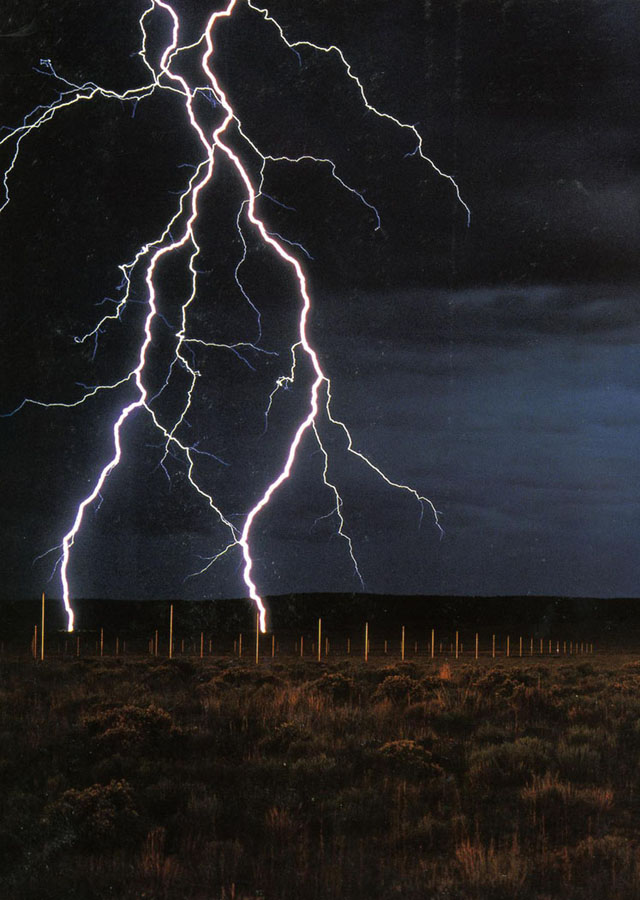

The shift in the ways that data visualizations of global exercise was read suggests the multiple ways that information in the most beautifully defined articulation of data might read. Rather than providing individual information, after all, Strava was aimed at providing a counter-map of exercise routes that its users might enjoy to orient themselves to an athletic sub-culture. But Strava’s users suddenly realized that as well as tracking the courses of ironman in Kona, Hawaii, or the Camino de Santiago across northern Spain or to provide athletes with needed motivation to explore new places, it rendered visible military presence that the government tries to keep under wraps in a permanent record of what seemed classified counter-image of an over-extended global military. The aggregation of athletic achievement gained popularity for providing a clever shorthand to convert exercise routes that gave striking legibility to a trillion GPS dat points in almost organic ways, in a form of collective observation for the greater good that had promoted its considerable individual health benefits to users. By tracing aggregate routes of runners over time in “beautiful data” by glowing lines of increasing intensity, it reveals the frequency of aggregate use over time, by varied intensity of rasterized data against a black background, recalling in their aesthetics the extended exposure of Walter de Maria’s photographs of the lightning storms that are intentionally generated in a New Mexico field in his permanent 1977 art installation Lightning Field—

Jamie Russell (BNPS)/Telegraph: Electrical Thunderstorms on England’s Southern Coast

Jamie Russell (BNPS)/Telegraph: Electrical Thunderstorms on England’s Southern Coast

–but to create a truly long-exposure record of collective commitment to athletic endeavor on a global scale. As de Maria’s long-exposure shots of night-time lightning strikes or those of emulators collapse time, which Bill Rankin noted as an artistic model for patterning data over time, Strava treated its beautiful dataset to aggregate increased use of routes over time; in the “exercise space” of the map, dense spools of the most shared exercise routes emerge as brighter lines as if back-lit from the street plan of a dark slate OSM base map, only to fade to black as one approaches its periphery, as if into an uninhabited shadowy dark zone, or terra incognita, of far fewer folk exercising with Fitbits, either less colonized by global capitalism or wifi. The glowing lines that track motion in Strava’s heatmap also offered a map of segregation of wifi, and stark divisions among who has devices transmitting geodata on global scale that was as arresting as a lightning strike.

Roger Hill

Roger Hill

2. The new sort of spatiality that these web maps create were not considered in terms of the patterns that they reveal in a global space, however, so much as a service. Indeed, they responded to the readiness to be encoded in the aggregate, and the reassuring logic that comes from locating one’s path in a sea of data; that was part of the huge appeal of placing oneself within a readable form in the newly mapped space Strava promoted to its users and as an emblem of its success. The far greater robustness of the new heatmap that eliminated much of the static of spatial distortions often built into GPS to provide a more precise and accurate rendering of position may have encouraged the migration of a map designed to render and orient users to fitness routes to new end.

For months after it was uploaded, the newly rendered dataset was realized to intersect in unforeseen ways with another register of the deep discrepancies of globalization; the Strava app revealed stunning capability to geolocate exercising soldiers who did not stop data sharing while on foreign service, the predominant interpretation shifted to charges of compromising global security policed primarily by American naval, military, and CIA bases in the very sectors of the world where tracking exercise was an interface adopted only by foreigners. The striking absence of coils of trails in sites such as Kabul, Afghanistan, for example, allowed on to use the app to zoom in to spots of brightness to reveal the footprint by which app users (overwhelmingly American) occupied. The same problem arises of betraying the presence of Americans in “coalition” bases in Syria by fitbit, Garmin, or iPhone tracking signals.

Kabul Strava Users/Strava Global Heat Map

Kabul Strava Users/Strava Global Heat Map

Civilians interested in tracking the Syrian civil war realized that the fitness app included stunning geodata on the 2017 exercise routes of all Americans stationed overseas, in ways that popped out so crisply to cross boundaries of state secrecy, even if Strava had been quite careful to protect the personal secrecy of users: the “beautiful dataset” they had promoted since 2015 in the first online heatmaps was understood as collective, which projected and promoted a sense of belonging. Strava boasted the ability to track the kiteboarding in Mexico, the Camino de Santiago trail across northern Spain, or an Ironman triathalon in Kona, Hawaii, after all. But users of its website discovered rather quickly what a good tool it provided to track their locations in a way that constituted a collective form of surveillance as well as being a data sharing app. If a clarion call to delink, and not aggregate, the sharing of geodata was suddenly problematic as its potential to be weaponized was revealed. Perhaps the closest to the a system of cumulative collective observation that has ever been made publicly available, the release shocked twitter users and made waves on the web, as the specter of data weaponization and a national compromise again reared its ugly head.

It is indeed eery that the release of the heatmap tracking fitness in November, based on aggregating geodata from smartphones, Fitbits, or GPS devices, was read for military content, given the broad-based commercial application for civilian audiences of the very sort of UTM map devised by the United States military in World War II as a form of accurate global observation and military monitoring of hot spots: the same technology was after all suddenly available to anyone who surfed the internet, even without any knowledge of cartography or reading CVS files or web-maps. The Op-Sec value and content of the web-maps were not described as not that terrific, but the data breach suddenly pinpointing US bases in Afghanistan, Djibouti, Syria, and central Africa seemed to pose a huge security risk, leading the app to try to clear its name when it urged military users to ‘opt out’ of heatmap’s anonymized view of over a billion athletic activities. But Strava refused to budge on its commitment to what was a huge promotional device many users loved to record their own positions in a sort of virtual notebook whose appeal lay in aggregating information of immediate legibility, as a post-verbal memory form that required no commitment of words to a text. Its insistence that accessibility of the beautiful platform be preserved reflected the fitness app’s considerable appeal by allowing athletes to view themselves in a map.

The public geodata of more than a billion users and boasting over three trillion GPS data points primarily celebrated the expansive interface of Fitbit users with public space, after all, and the range of physical activities in which users engaged. The app was understood as one of orienting athletes to space-use and space, illuminating places largely off the grid and providing tracking tools to make riding, walking, and especially running better–it was even a way of enticing users to experience areas that come as close as we now get to a sense of the wild, or use the space of metropolitan areas in Strava Metro. The new iteration even allowed users to correct GPS approximations that placed users near to the closest roads, providing a crisply rendered picture of exact location, not distorted by road geometry. And the company eagerly and rightly promoted the availability of ten terabytes of raw data input designed to last forever–outlasting the territory, and even outlast states, rendering itineraries across borders, and allowing users to filter defined privacy zones, to ensure best use practices. But when the data is up, the data is up, and habits die hard. And at a moments of accumulated global military tensions, the Strava map brought down public wrath as it was charge with having “give[n] away the location of secret US bases” and inadvertently alerted any audiences who cared precise locations where marines and embedded military chose to run, and even enabled anyone to identify multiple secret centers of CIA satellites.

3. The unforeseen risks of sharing or providing geodata–even if it is not particularly revealing of an individual– on open platforms have only begun to be assessed. The absence of attention to the distinct demographic an app like Strava might attract, perhaps even keen in some ways to see themselves as contributing to a new global art form of the interlinked, and initiated in reading the most popular itineraries in their community, was identified with relax, stripped of geopolitical content of our increased proclivity to global confrontation, however, removed from the politics of a globalized world and providing a means to segregate the personal from the political–so much is evident in Strava’s claims to preserve for eternity the “unique pentagonal pattern of Burning Man’s pop-up city . . . [that is now] forever etched into the Heatmap,” rather than describing global inequality. The globalism that Strava heat maps have gained have provided particularly stunning keys to map the military expansion of western states.

In many ways, the promises of Strava were a next generation iteration, on a truly global scale allowed by new levels of geodata aggregation, and our readiness to find something validating in being tracked en masse–or tracking in an alternative to something like the “my year in running” map that implants trackers in one’s very own Nike, creating a powerful visualization of one’s place in collective space of running, created in a 2012 aggregation from thousands of such Nike+GPS sensors–to visualize the preferred trails for running in New York City that collapsed collective itineraries of participants over a year that created a community’s or micro-culture’s record of athletes’ engagement in the city’s public space. Rather than suggesting the notion of walkability, the map seemed to reveal the choice routes of running, from the Central Park Reservoir (heavily ringed, with the roads through the park, and the roads along the Hudson River, and several crosstown routes.

Zach Lieberman, Emily Gobeille and Theo Watson

Zach Lieberman, Emily Gobeille and Theo Watson

The next generation nature of Strava’s software and the greater benefits of OSM base maps was illustrated nicely by the oblique image of Moscow’s heatmap of Strava users, which used Mapbox GL’s rotate/pitch feature in a classy way that illuminates the ring-road nature of the city grid to foreground the running options it offers.

Detail of Strava’s Global Heatmap for Moscow, Russia

Detail of Strava’s Global Heatmap for Moscow, Russia

The fact that Strava’s heat map crossed the national boundaries that are minimized in OSM presented an advantage for representing exercise routes, and athletic performance, in a new context. But the same web map raised the specter of a leak in data to non-state actors. While Strava Labs is working to provide simpler “privacy and safety features” to customers so that they can control their data, the ‘benign’ form of surveillance. But with the rise of public services that incorporate geotagged visualizations of exercise apps, the public circulation of broad patterns of exercise, and the potential access to individual “fastest times” of the users of the fitness app raises questions not only of individual privacy, but of the preservation of what may have been thought military secrets: as the boundaries on personal privacy are ever shifting in an age of social media and satellite monitoring, they are bound to impinge upon the protection of ‘state secrets’ as divisions between the two diminish.

As satellite data makes geolocation available on a common market, as a feature of the Fitbit or iPhone, the forms that are revealed about the aggregate pose problems that we have not understood by focussing on personal secrecy and security alone. The forms of data-sharing that they offer users was in fact long realized to have the ability to allow others to access geotagged locations. It remains to be seen how to reconcile such wildly popular technologies of picturing athletic exertion–“lite” forms of surveillance–to the public good, and reconcile the demand for picturing oneself in a self-congratulatory map of exercise regimes into the growing codes of public secrecy that seem an inherent part of overextended political regimes. The problems might start from balancing the “right to be surveyed” against the public interest, however, not against state secrecy. The fingers that are pointed at soldiers for “revealing sensitive and dangerous information by jogging,” as WaPo put it, or the patriotism of the folks at Strava labs, ignore the problems that might be best described as an addiction to self-mapping and social media posting, or the addiction to devices that seem to insulate many Americans stationed overseas.

4. The boundaries of national security and international information are increasingly blurred, and the comfort that most Americans feel, and actual eagerness to broadcast their actual exact geospatial locations, suggested the stakes of the weaponization of information. As President, Trump has promised vigilance in the face of cybersecurity dangers that had expanded in the Obama administration to create a new sense of national vulnerability, to security breaches, vulnerable data on financial transactions, personal privacy, and indeed of national security plans; fears of personal and public vulnerability are feared more than ever before; but concerns of limited recognition of the danger of national security threats has grown across communications systems. Despite a warning last summer of the recent warning of the need to bolster defenses of private systems for foreign attacks from the National Infrastructure Advisory Council, who were struck by an absence of foresight in safeguarding of the private sector’s cybersecurity. And although they voiced concerns that “there is [only] a narrow and fleeting window of opportunity before a watershed, 9/11 level cyber attack to organize effectively,” and create new incentives to promote cybersecurity, there has been little response from the Trump administration, and recent attacks on the FBI and fears of a failure to prioritizing the safeguarding of security or intelligence interests in relation to intelligence-gathering services threatens to prevent assessments of vulnerability to information breaches.

In this climate, the ways an app destined for personal use in logging the time spent exercising seemed to portend fears of future, larger data breaches. The vulnerability is one to which the President seems not oblivious but poorly prepared to prioritize. As President, most of Trump’s has consolidated command, but has also undermined actions of the very law enforcement agencies who are tasked with safeguarding and monitoring national security. The increased scope of data vulnerability and the possibility of data weaponization has exponentially grown as many has signed over their privacy to iPhone apps, essentially generating exponentially more data than we are ever able to protect. The fear of the narrative of the release of state secrets that the Trump administration seems to have stoked by breaches and hacks in recent years–which alarm at the “theft” of personal data on Wikileaks has fed–gave new legs to the story of the breathing of confidential security secrets for all to see on a heat map of a fitness app. And narratives spun widely about the huge compromise of state secrets and security when the app broadcast an international map of the hidden locations of clandestine annexes and bases, isolated in landscapes without many other folks using exercise apps nearby.

Strava heat map shows signals in and around Kabul

Strava heat map shows signals in and around Kabul

5. What became known as a huge data breach had been visualized by the California-based fitness app with little sense of releasing state secrets, but it also suggested a new threshold in the weaponization of data that had been allowed by the inevitable intersection of the huge growth of the concealed or “dark” clandestine government activities and the thickness of the data seas in which we surround ourselves to alert folks to what we’ve done and that we’re here, or even to track our own information, not in words, but in apps that let us know exactly how many times we commit to exercising weekly, and the extent of our runs. We are all so well tracked that we can be mapped without hacking or cartographic skill, and the visibility of the most intensely used running routes of military servicemen seemed not only to place them at risk, but raise a visible image of the extent of American presence in many regions that have been kept “dark” of the American public, and often also kept “dark” by our allies to publics of those nations. Could the maps even provide propaganda about the extent of an interloping but aggressive scale of American military presence abroad?

The unselfconscious sharing of personal geodata by American operatives and military abroad was the source of the “leak” rather than app itself, as the absurd juxtaposition of data meant to remind us of our relative fitness, heart rates, and distances of work outs has, in its aggregate, with the revelation of issue our global military footprint. While the data wasn’t personal at all–or even tied to individual patterns–an apparent addiction to broadcasting geolocation increased the collective vulnerability of the American military in particularly delicate sites from Mosul to Chabahar airbase. And with the potential risks of the release of data of the fitness app Strava, the narratives of what constituted a data breach of national sensitivity suddenly spun out of control.

The fear of the public online revelation of locations of U.S. military in much of the Middle East and third world where fitness apps were used by few not in the U.S. military or intelligence services suddenly rendered them far more visible than the most users of the fitness app could have foreseen: familiar with sharing data of runs, personal bests, and allowing themselves to be surveilled on social media, few predicted the extent to which aggregated geodata would allow illustrate our military presence so concretely by how a Fitbit app designed to track and monitor personal bests could track American military presence at secret compounds, military bases, missile sites, and CIA centers from Kabul to Syria to Niger. Perhaps the real surprise was how great this overseas clandestine military presence is to Americans who spend time tracking how many miles they run each week. The aggregate geolocated data compiled by the tracking app showed less of an athletic playground than something immediately perceived as having the flavor of a secret military map,–and one could imagine the intense laps run around military buildings.

Suddenly, one strikingly had a far better sense of American presence in Kabul, either for runners in the American military who worked out running around military bases whose tracks seem to reveal each an every site or hidden installation on an OSM base map in which they seem the sole users of the app which is doing the aggregating–

or indeed zero in on tracked exercise routes nestled in the mountains of greater Kabul–

–in ways that one might read against a Mapzen Metro Extract of Kabul,

© Mapzen, OpenStreetMap, and Leaflet

© Mapzen, OpenStreetMap, and Leaflet

The clear contrasts that arise in such fitness tracking apps are brilliantly visible between the states of North and South Korea, although the striking presence of a few bits of bright illuminated trails near or in Pyongyang raise eyebrows of their own as to what sort of hidden presence Americans might have in the city–if these are not only American students or businessmen abroad.

The shadowy city streets of Kabul or the dark regions north of the DMZ between North and South Korea quite sharply contrast to the over-illuminated aggregations of intense physical activities along the intersecting grids of San Francisco, where self-tacking seems so universal for the distinctive city grid to leaps out at the viewer, each street illuminated to some intensity in a topography defined by running, biking or foot traffic. Residents may not be more fit, but data sharing and self-tacking is all the rage.

7. Strong parallels between deep disparities of data-sharing and indeed access to apps intersected with the very sights that American forces have come to patrol most intensely in ways that reveal a world suddenly not so invisibly divided by data-sharing practices. For in ways that starkly reflects the uneven use of the vanity exercise Fitbit devices and smartphones in countries where US military are engaged–sites like Syria, Somalia, and Iraq, where military members provide concentrated users of such devices in disproportionate relation to other citizens, the extreme rarity of folks running with Fitbits who are not American recasts the “social networking site for athletes” that shares personal data into an alternate platform for mapping multiple secret installations across the world in crisp geolocated detail. And while soldiers can turn off the data-sharing when wearing devices, it seems the lack of any military practice or policy for not broadcasting one’s spatial location has offered a model for harvesting data based on American penchants for location sharing, as the California-based running app gains a new and unforeseen functionality overseas.

And when the widely-used fitness app Strava decided to go public with a heatmap that made available updated geodata on exercise routes of up to one billion people, it inadvertently alerted any audience who cared exactly were marines and military chose to take their runs. In ways that immediately reflected the deep disparities of fit bits and smart phone among many of the countries where the United States military are currently engaged–Turkey; Syria; Afghanistan; Somalia; Iraq–the release of the heat map was something of a massive data drop. In an age of the widespread adoption of devices recently billed as enhancing our own personal well-being, have we inadvertently created a security threat?

8. Whereas many athletes who use the app to track their personal bests may be based in Northern California–witness the density of tracking in metropolitan areas like San Francisco and Berkeley that certainly light up as sites of intense activity, as well as much of the peninsula and San Jose–

–in ways that seem to promote a sort of barometer to the health of population, that is not coincidentally congruent with the density of the use of social media, or access to iPhones.

Needless to say, the transposition of the fitness app to the Americans serving in the Middle East and Africa was a data drop indeed, if of unintentional scope. Strava rarely considered the incidental information–or collective casualties–that the aggregation of collective data might cause. Indeed, habituated to aggregate groups of fitness freaks in densely populated regions where use would snowball over time, they believed the level of individual privacy compromised was minimal, and felt that the global map compiled so many data points to make the revelation of personal stories–or private information–a non-issue. Even when you foregrounded running routes in the region, the story that emerged was one that was collective, and could hardly be conceived of as individual.

But the patterns of aggregate use by US Military who, admittedly, left on their location-sharing were suddenly visible not in a crowded field, but in near-isolation–and even if the setting is the default, it was striking that the more remote the areas, the crisper the itineraries of individuals wearing their Fitbits as they ran, bicycled or climbed grew. Sites where there were more removed CIA bases or annexes, staffed by men and women who ran in close proximity to their stations, even popped out more. There are some cool almost abstracted instances of running paths echoing graceful strobes of an intricate dance, generating some cool color exchanges and contrasts in a heatmap that seem irrespective of place. One might imagine neat curving graphics created by the app tracking running, biking, skiing, and other sports against Open Street Map base maps–

9. The elegance of the images might the personal self-exposing artistic projects of Jeremy Wood, who has for sixteen years has rebutted the intrusiveness of personal geographical tracking by tracking his itineraries in London, in ways that serve as a sort of personal exposure of his location within a surveillance state. And much as Wood has produced extensive time-lapse tracking of his location in works of art, casting composite records of his personal travels against a black background to create suggestive visualizations both of his intense attraction to the metropole and the traces of his individual presence that geolocation can reveal, the images create a composite footprint foregrounding the white-hot intensity of theseveral London neighborhoods whose streets Wood rarely left.

Whereas Wood aggregated itineraries over time to create a ghostly trace of his perambulations, the work evokes surveillance in its personal traces in a sea of black. Although Strava does not see itself as releasing personal information, nor indeed as releasing what is understood as information, the Strava app was quite quickly faulted for creating the sort of security breach that revealed its corporate recklessness. For its part, Strava took care, to be clear, not to reveal private data by collapsing aggregated exercise routes of users who seek to track their heartbeats and speed while running or biking over time, and create a collective image of where they go, but were less mindful of turning off the functionality of sharing of location, and whose commanders saw little importance in cautioning against using the devices to track their performances as they ran around the base. But in ways that seem less an inversion of surveillance than an actual form of surveillance, the Fitbits served as embedded chips on cats or dogs, placing viewable evidence of geolocation in a dark data sea.

The supposed shock of the unsurprising release of unlocked geodata as “breached” data seemed evident in the very images American military going out for intensely restrictive unimaginative runs, unwittingly broadcasting their exact locations. The information released by much fitness app data was not considered highly personal, although the app permits one to follow a given individual over time. Indeed, in most sites, patterns of running tell us about space and spatial difference, but don’t seem to compromise individual privacy. It’s interesting and eery to observe where young run in a divided city like Jerusalem, avoiding the occupied territories, but one is haunted by the sense of space of users who return to the same roads or concentrate in local hilltop settlements.

Such stark divisions between lived ad political space may be understood primarily in terms of who possesses access to the App, resulting in the crispness with which we can view two worlds as coexisting beside one another in the city and on the territorial boundaries (or really confines) in which many run, and the limited sense of open space which many Jerusalem runners share. (One might propose a study of social segregation, were it not so difficult to separate from the distinct demographic Strava attracts and the interactive devices of transmitting geodata on which it depends.)

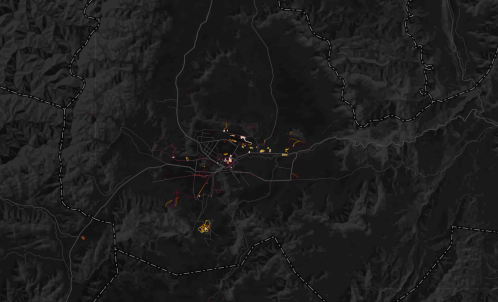

10. When Strava promoted its heatmap as a statement of the huge global scale of its users and its global popularity, the release seemed relatively anodyne if of aesthetic baeuty. But it became relatively quickly evident that the data-sharing app tracking every run by a soldier wearing Fitbits provided a way to share not only whatever cool running route they found–even at Chabahar airbase in Iran–but to broadcast their locations to a global audience. The fitness app unintentionally to expose young men and women seeking outdoor exercise despite the constraints of service abroad, and probably wearing Fitbits as fashion accessories and not conscious of their function of information sharing as they are seeking to clear their heads during active duty.

These modern icons of exercise are unintentionally act to reveal place, let alone reveal the hotspots of a globalized world. If imagined to broadcast itineraries to a network of users who might well be expected to have little interest in geopolitics, placed in context, they reveal state secrets. No clear response exists to the data that has been publicly posted, save to urge military users to shift their default settings and ‘opt out’ of the heatmap. Some of the shared data might make one considerably jealous, or inspire a similarly freeing run. One run at Chabahar airbase proved to provide some great examples of beautiful settings—

–but the big bombshell, however, was the release of running courses where one didn’t want to see large groups of Americans, and the big question was what sort of narrative should be told about it, and where blame should be placed–or the data contained, and the individual bases that were suddenly apparent to all who sought to look, and indeed revealed the roads where groups of soldiers may have gone running together that betray the distinctive grid of a military camp.

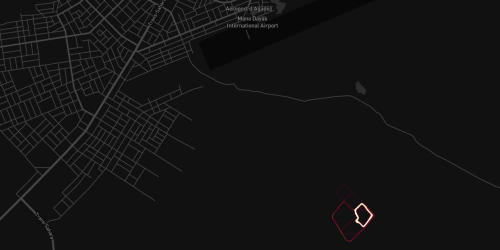

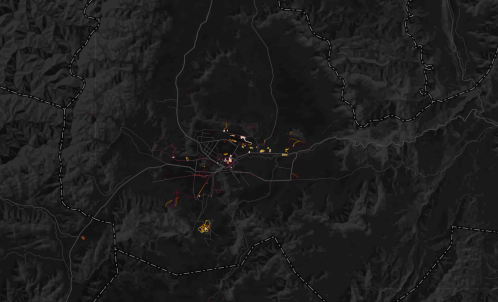

Sections of the heatmap unintentionally revealed what would be considered state secrets on a brightly lit global map with astounding precision that can document the collective patterns near bases in Syria, Yemen and Turkey in ways that have caused the Pentagon to decide to review GPS policies of armed forces abroad in areas where few native Strava uses exist–where the live tracking of users pop out of the maps like bright lights across much of the Middle East, which lead Marine Corps spokespeople to caution of the need for “situational awareness” as they share military information–although mucht of that information has been already shared. Secret military installations “popped out” of the social networking app across the Middle East, isolated from other users of the app,

Strava Heat Map; Screenshot by NPR

Strava Heat Map; Screenshot by NPR

Data shared on maps seem to have created a degree of unintentional openness that reminds us of the surveillance origins of many of these tracking devices, and of the close relations between mass market gadgets and the intrusive nature geocoded data, if the relation between such gadgets and the revelation of state secrets is relatively new. Again, we are reminded again that the civilian adoption of GPS may provide the ultimate way of sharing knowledge across borders, and social media of digesting it among whoever has power to download. The eery undercurrent to globalization may be the ease with which personal exercise runs the risk of undermining state security–by providing far more information to any enemies. Taking a run with a Fitbit on enemy soil might even be one of the easiest ways to disclose the location of a secret base.

The release of a heatmap let American runners who were avid fans of the app doing laps around bases in Mogadishu, Mosul, or Al Tanf in Syria pop out in detail, as the breach of personal data broadcast the mundane task of running around the “base” for the world to watch. In an age of the massive adoption of devices billed as enhancing our own well-being, have we inadvertently created a massive national security threat? Even more–has the range of data so freely uploaded to Strava globally creating a security nightmare for allies of the United States and other governments across the world? For in ways that seem to undermine the secrecy of military presence in bases across the world, soldiers who think they are clearing their minds are exposing long-secret sites of military presence that have never been so openly pinpointed before.

It is all the more galling as these folks were just going out for a run, but didn’t see it a risk to do that without a trusty fitbit.

While not so popular among foreigners, Fitbits are all the rage among young military-age westerners, as fashionable accessories; the very rage seems to risk revealing the global footprint of the US military with far greater precision than anyone in the Pentagon would really want to be public record. And given the recent location of American soldiers in poorer nations in the Middle East and Africa, its not surprising that in a place like Niger, the presence of those groups of Americans seeking to get their exercise pops out with amazing readability in a country where the drone base is the only site with folks fitted with Fitbits using Strava apps.

Bases with American soldiers light up at night in Syria, similarly, giving an unprecedented visibility to American forces that seem to designate us as the victims of needless peripherals that have come to dominate much of our lives, as well as dupes whose sense of vigilance to privacy settings have been compromised by smart phone addictions that were not that smart at all.

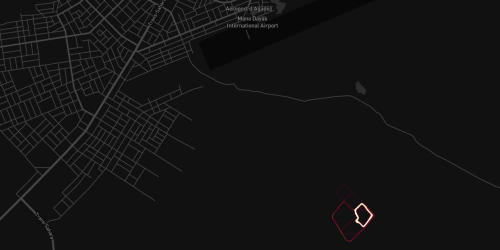

The alleged CIA base/annex in Mogadishu’s airport in Somalia, for example, pops out in an eery gold outline, as Adam Rawnsley found, as if to suggest a mandated running route that seems, in fact, quite beautiful to extend across the Somalian shoreline, clearing their heads while inadvertently letting the world know their location

11. That the Strava heatmap could serve not only as a fitness app, but a means of revealing the locations of secret military sites, seems a revelation of the division of the world in two worlds, and two levels of willingness to be tracked. But Fitbit seems to have provided a means of tracking “the few, the proud” and other military, in ways that have become a crisis for operational security: without even being hacked, Strava has offered a data dump from which anyone online was invited to search possible sites to glean information about what suspected secret locations. It fell to an Australian college student, who is “not very fit” who was consuming online news about Syria to notice the extent to which Syrian bases–or U.S. soldiers–would pop out of the heatmap Strava released, as a sort of open source intelligence, exploiting the tools of geolocation wired ,into the app. Indeed, before releasing the information publicly, twenty year old Nathan Ruser had discussed the question of using Fitbit data to track Americans in Syria in chat rooms, using the Strava map, given or inspired by the clear discrepancies in the global heatmaps that Strava Labs provides online, with upwards of a trillion GPS datapoints:

Indeed, the dark areas of the map provide the most useful terrain to spot Americans exercising abroad, seemingly using Fitbits that they though were a form of normalcy, if not only a bit of their pasts, into the new, remote terrain where they served.

While not designed or intended as a way to release records of location or track individuals, the decision of Strava to release the information seems an attempt to plug the global adoption of the app, Strava CEO James Quarles reminded the public that he had done his best to respect individual privacy, but reminded us how few of us ever use the opt out settings. The service is not openly doing anything wrong, of course, although it might have been prudent about releasing the map; but it uses a model of data harvesting whose users would do well to take more precautions about. Once linked to an Open Street Map images of the roads around Mosul, as above, anyone could use the heatmap to pinpoint the location of where US military exercise in ways that the White House would long to find Al Qaeda fighters to adopt to pinpoint their positions.

The apparent universal use of Strava in Taiwan not only suggest the far greater diffusion of the app than their less westernized neighbors on the mainland–

Strava Labs

Strava Labs

–but offers a basis for local mapping of military installations the country would like to be kept secret, and suggests the degree to which such harvested data leak state secrets with pinpoint precision. Indeed, although running is by its very activity a declaration of open possession of the streets and of space, the clear rings and routes along which Taiwanese run around the site of a secret missile command site that runs the cruise missiles that are oriented to the mainland located in the headquarters’ parking lot; while intended to be kept secret, it is quite frequently jogged around.

Exploring the global heatmap of runners doing laps around the camp in Djibouti, the intensely bright definition mapped Americans’ daily routines with surveillance-grade precision, as soldiers and security patrols inadvertently released their own tracked positions as they were only trying to clear their heads outdoors, and running in what are probably the proscribed routes for running in areas they don’t want to be vulnerable–but in so doing make possible CIA sites as vulnerable as could be imagined. There’s a lovely logic about Strava reminding users of the option to turn off sharing location, a feature the smart phone industry has been making money off, or seems poised to be.

Poor guys using Strava devices to exercise, one thinks; they were unaware they are embedded with locating devices, like cats or dogs embedded with chips–when all they wanted was to track their heart rates and elevation shifts in high temperatures, or just track the intensity of their workout times. But such poor oversight of data release protocols while living at sights of security. With Americans deluged by the desires on the market, and Amazon providing Fitbits to track their own well-being, the rage for sharing personal data seems set to expose the underbelly of the body politic to danger.

Daniel,

This is truly superb work, fantastic; why mainstream media outlets do not syndicate this blog?

Congratulations, I really enjoyed it immensely.

istvan

________________________________