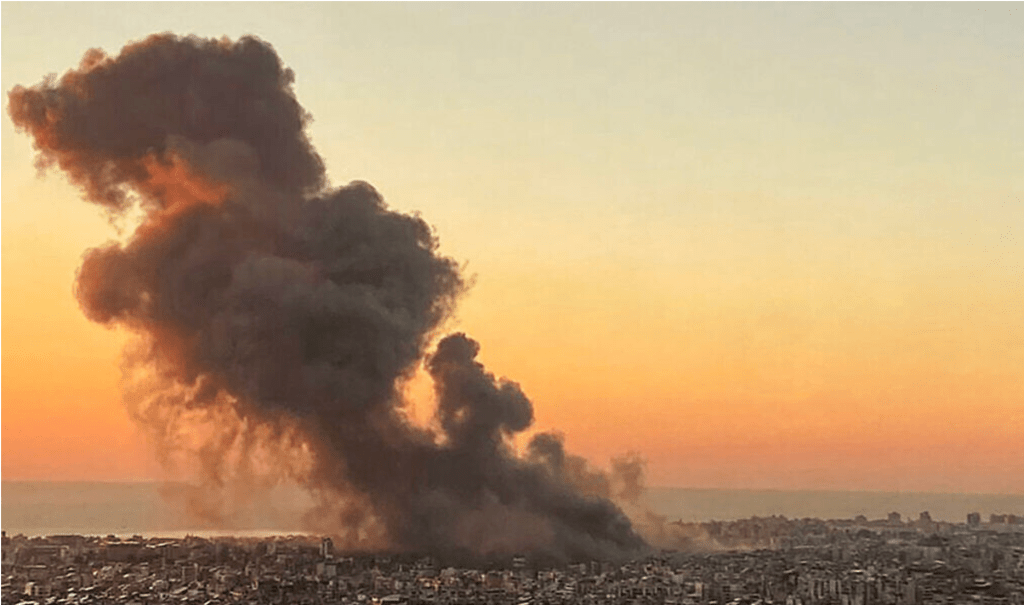

A pillar of orange smoke rose over Dahiyeh, outside of Beirut, the site of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah’s death, on the night of September 27, creating a crater some twenty feet deep. As local residents flooded shelters in downtown Beirut from the southern suburb, the intense bombing illuminated the night sky an extreme show of force that Israeli Air Force knew no boundaries in the control it exercised to defend its borders across the Middle East. Dozens of precision-guided bombs that enetered four high rises were designed to penetrate heavily fortified bunkers or caves with a thirty five meter radius; the bombs exploded at time delay after entrance, destroying the four buildings with a force three times of bombs dropped by United States in the Iraq War. The headquarters Hezbollah used to coordinate military responses since October 8, 2023 was reduced to a fifty meter deep crater as large as an entire city block in Beirut’s southern suburb, erasing its presence.

The airstrike that killed Nusrallah together with seven highly ranking Hezbollah commanders and officials from the powerful group sought to paralyze the deep commitment to support for Hamas on Israel’s northern border, and the increased flare-ups along the occupied Golan Heights. The massive explosion of dozens of bunker-buster bombs–designed for fortified compounds, more than residential settlements–itself mapped the overlap between militants and civilian residences that Israel had long argued non-state actors had taken advantage, using communities as human shields, and has led to the blurring of so-called “safe zones” that have so tragically become sites for the massacring of innocent civilians with a regularity that is truly hard to stomach, that has provoked global indignation, which the airstrike against Nusrallah–followed by killing Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar after he was encountered in a civilian zone in Rafah, a city on the Gaza Strip’s border with Egypt. The massive scale of the vengeance strike in Beirut was a response to the tranquility of the AI scene, suggesting the deep evil character of the non-state actors and disabling their abilities of resistance.

The massive explosion of military munitions in the Beirut suburb didn’t erase a global threat posed by militants–but rather magnified it, escalating cross-border violence to a new threshold and level of destruction with a rapidity that is unprecedented. The complex politics of the Middle East since October 7, 2023 were cast as a conflict of good and evil, but the execution of the Shiite Muslim secretary-general long designated a “global terrorist” reconfigured a long-simmering local border conflict as a war far beyond its borders, or the safety of those borders. Indeed, the air raid was a transgression against the very authority of or respect for borders in targeting non-state actors within a narrative beyond states. The fear of a global threat–a threat to the Jewish people only able to be understood in global terms–that Nusrallah propounded justified the huge deployment of force, magnifying and realizing the rhetoric of destruction as an escalation that can only be understood in retributive terms of a lex talionis, outside either international law or the laws of war.

The strike at the heart of Beirut’s residential neighborhood was a qui pro quo responding to attacks on Israeli territory. The attacks were on territorial claims long denied by Hamas and Hezbollah–but the retributive strike of long planning was a proof of concept of the power of the Israeli Defense Forces had to strike–and indeed flatten-any village in Lebanon to protect its own frontier, civilian loss of life discounted. The assassination was a demonization of all civilian infrastructure violating international law, but presented as a retributive strike for a higher good–a “measure of justice” to achieve war aims, and a map of frontiers, escalating the violence of the war on civilians beyond earlier wars, even amidst current calls for de-escalation. Rather than map the war by frontiers, or by national borders, the attack on the stronghold of the non-state actor in Beirut flattened four buildngs to kill its Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah and elite, blurred boundaries of civilian casualties and military targets in violation of international law and legitimate tactics of war. The bunker where senior leadership convened for strategy seemed an actual bonanza. But in expanding the battle beyond Israel’s actual frontiers, yet of utmost urgency as a jackpot strike against the leadership who had perpetuated the assault on its northern frontier. The Israeli Defense Forces boasted, “Hassan Nasrallah will no longer be able to terrorize the world” spoke to the globe–as if justifying the huge show of force–three times the bombs of the “shock and awe” Iraq War on a Beirut suburb as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addressed the United Nations.

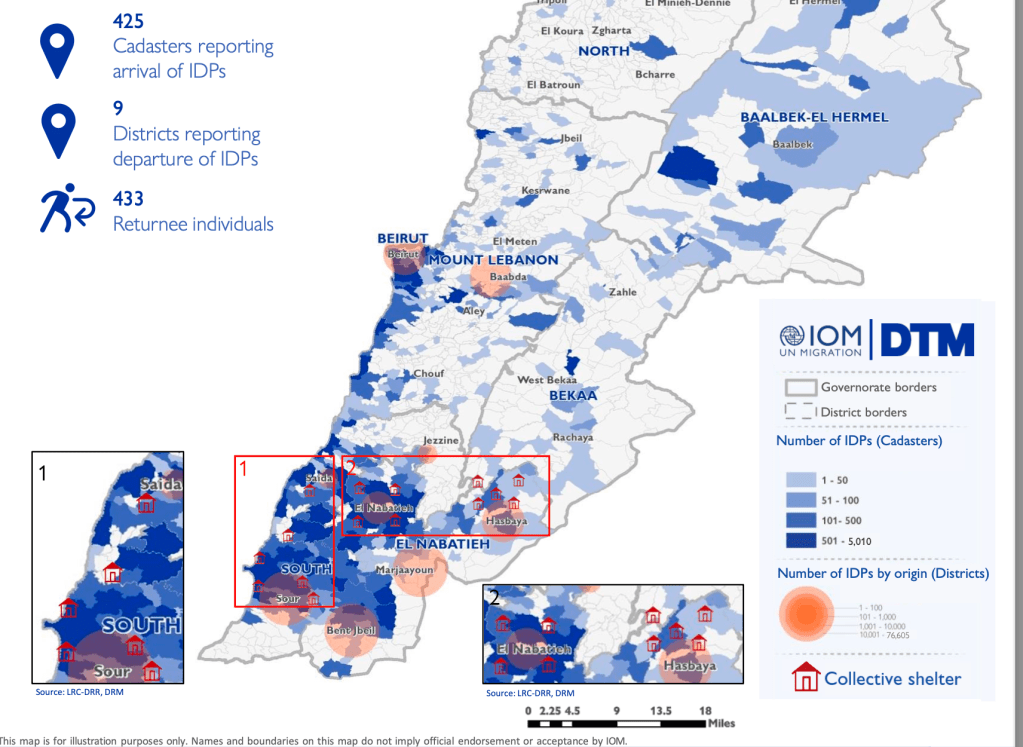

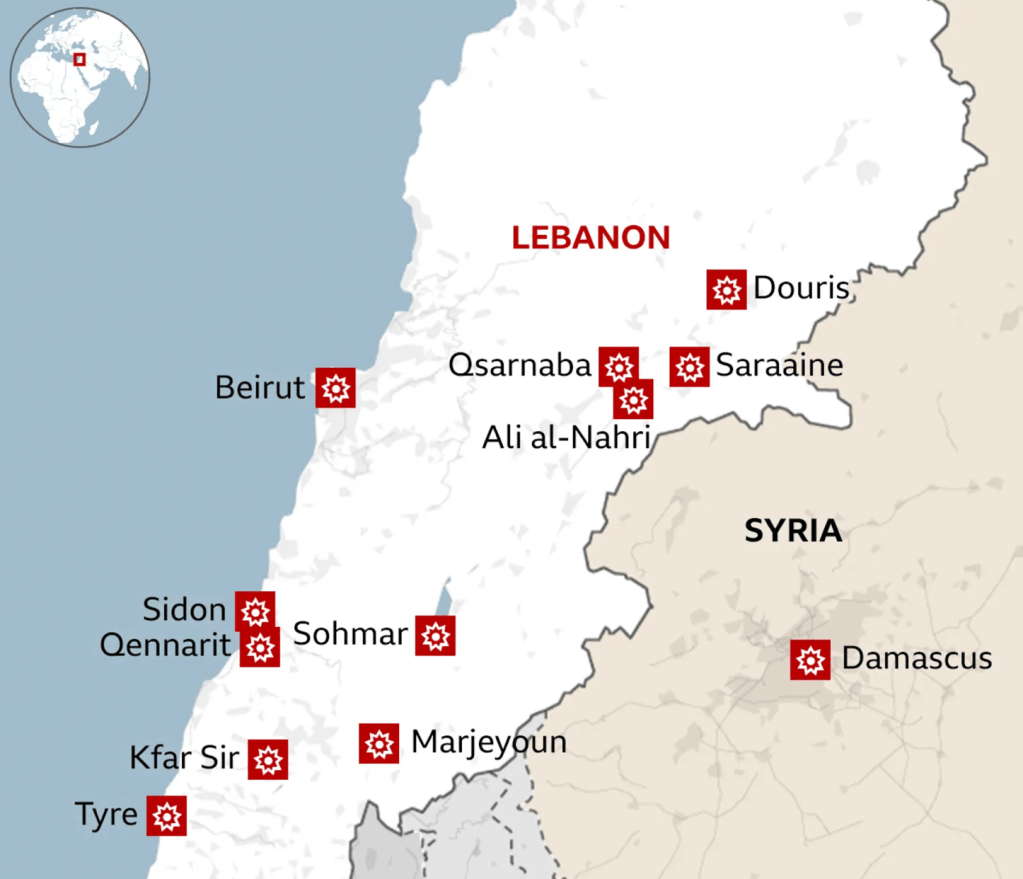

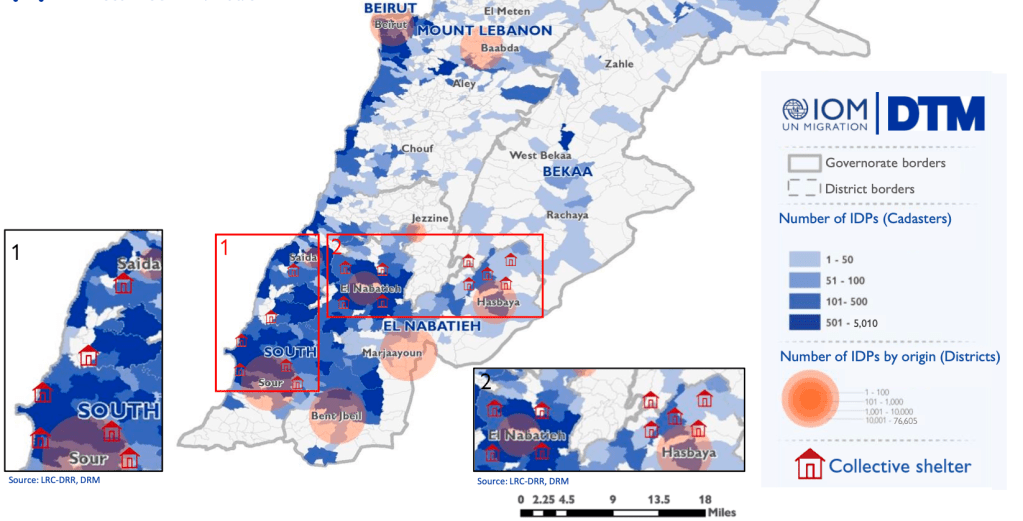

People Displaced During Armed Confrontations on Southern Lebanon Border from October 8, 2023-August 22, 2024/ Mobility Snapshot by International Organization on Migration (IOM) Based on Daily Monitoring/UN

The strike was an explosion not only of six apartment complexes, but an illustration of the power of a retributive logic of cross-border attacks, a logic manifested the violent military exchange across borders that have led to the growth of evacuation zones, non-man’s lands, and dead zones. Whereas the unclear locations of the Israeli hostages in the tunnels of Gaza City were not known–and while the leader of Hamas, and mastermind of the October 7 invasion, Yahya Sinwar, has long surrounded himself with “at least twenty hostages” per the expert on the conflict who interrogated him for Shin Bet, Kobi Michael, who continues to elude Israel Defense Forces in the Gaza tunnel networks. The assassinations of Hezbollah leadership flouted borders to send a message.

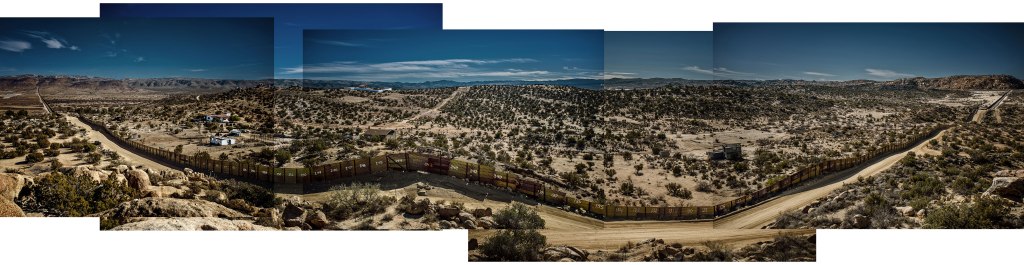

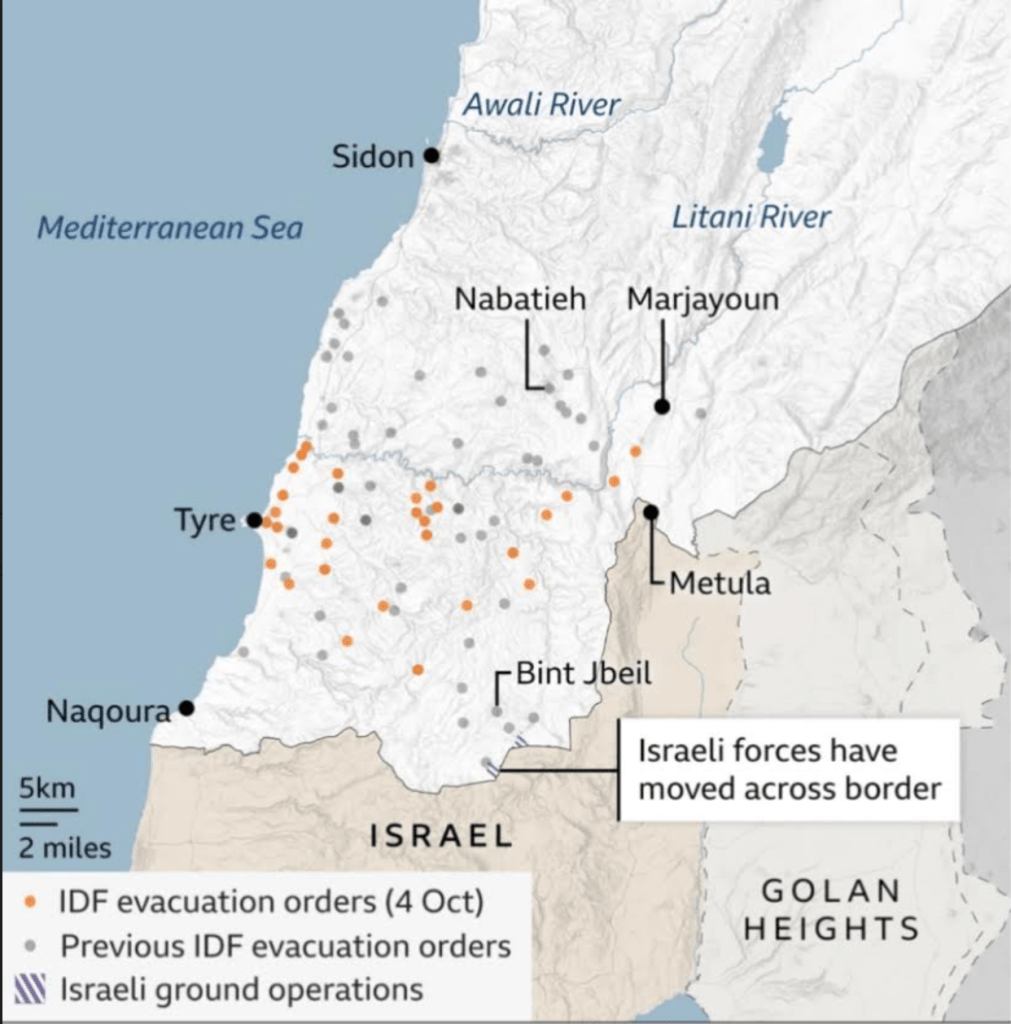

The bombing escalated the exchanges of rockets fired from southern Lebanon’s territory from early April, as border tensions on Israel’s northern border heated up, all but invoking a higher narrative of collective memory to sanction destroying infrastructure for staging attacks in Southern Lebanon on northern Israel. Israeli Defense Forces Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari “contacted the residents of the three buildings in the Dahieh” living in units “above and near Hezbollah’s strategic assets must evacuate immediately for their safety and security,” blaming Hezbollah for placing their lives at risk by burying “strategic capabilities . . . underground in Beirut,” demanding a bomb of requisite force in a residential neighborhood by a surgical strike as itself an abnormal violation of the law. (Hagari indeed advocated a surprise reprisal attack on Lebanon after the October 7 invasion, not Gaza.) In the year since the invasion, Israeli forces fired some 80% of rockets across the border. But the assassination of Nasrallah together which Hezbollah’s high command was followed by the displacement of a quarter of Lebanon’s population–some 1.2 million innocents, a mass exodus is rarely mapped–poorer Lebanese citizens; Palestinian refugees; migrant workers, and Syrians, and killing over 1400 residents of the region.

Displacement of Lebanese, Palestinian, and Syrian Civilians from Lebanon, October 8, 3023-August 20, 2024

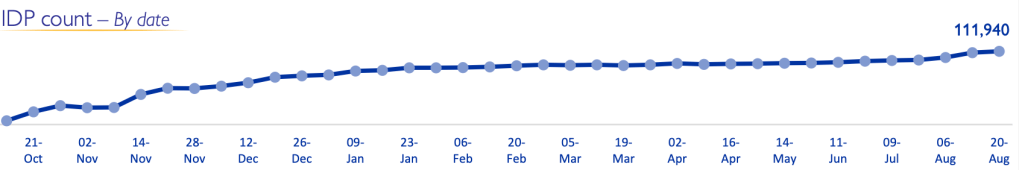

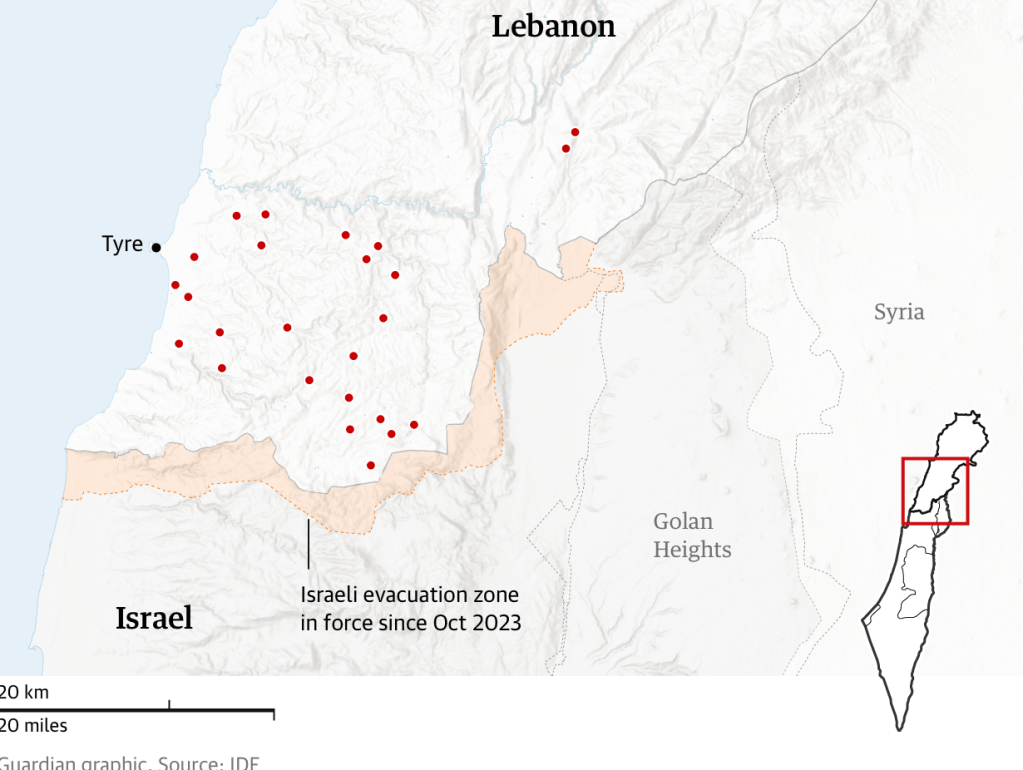

But the redrawing of the lines of “normal” interaction of the strike–and in the war–was predicated on erasing the idea of clear parameters of safety or precaution, expanding the battle zone in ways that frontier and border disputes can no longer illustrate or explain, as we map the “evacuation zones” imposed by the Israeli Defense Forces based on the data they released against the border which has ceased having much practical (or even tactical) meaning any more. The dispensing of the border as a unit on the map seems to have been the terrible result of the logic of this war.

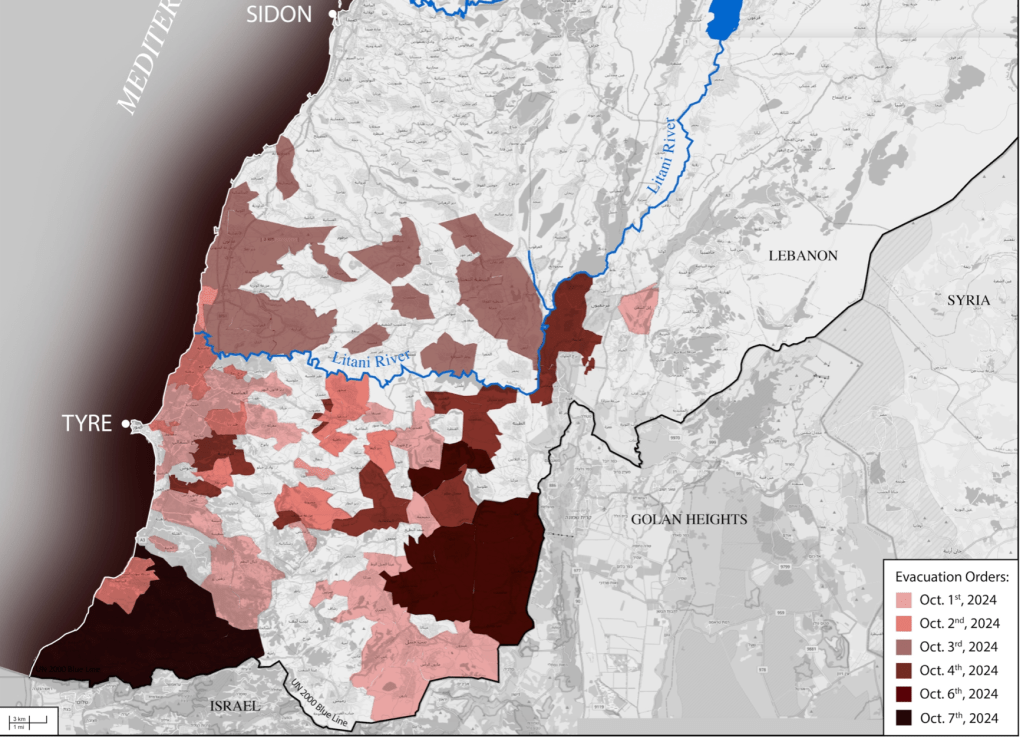

Guardian/Evacuation Zone, October 1

BBC, October 8, 2024/IDF Data, OpenStreetMap

These “warnings” may arrive only a half hour before the start of bombing, as if their delivery has become increasingly perfunctory, provided as a script to undertake the bombing of a broad sector of the border zone the first week of October, per a recent map of Amnesty International, rather than in a manner that would allow civilians to plan evacuations at all, researches like Ahmad Baydoun have found, trying to track not the arrival of bombs by IDF data, or their effect and impact on the ground, but the communication to residents living south and north of the Litany River.

Villages and Regions Impacted by Evacuation Orders, October 1,2024-October 7, 2024/Ahmad Baydoun, OSM

The frame of reference for the barge of such precision strikes are increasingly cast in terms of divine wrath and retribution–and the killing of Hassan Nasrallah charged with opening a “northern front” against Israel, linking that war to the army’s defense of Israel’s borders. American President Joe Biden explained the strike on Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah as a retributive act–“a measure of justice for his many victims” –echoing the apocalyptic terms Netanyahu cast the war, by a Biblical frame of reference as much as a geopolitical explanation. Indeed, while this is a war pursued on non-state actors–Hamas; Hezbollah; the Houthi in Yemen–the tribal terms in which they are cast by reference to Amalek, often tied to the “chief of the sons of Esau” in the Bible, as a nomadic tribe of ancient Israel or Canaan–who came before all other nations to make war on Israel, or to the descendants of Esau, whose tribe first encountered the ancient Jews as they came “out of Egypt,” and were the first and primal enemy inhabiting the idolatrous cities that demanded destruction–destroying the original inhabitants of Canaan to fulfill the covenant with Abraham, for a conquest in a Promised Land. If the October 7 attack reawakened Israel to the fact that the New Middle East could not avoid the Palestinians, it led to the evocation of the Amalekites, leading Netanyahu to invoke Amalek, as if prompting the involuntary memory of collective recitation, “You must remember what Amalek has done to you, says our Holy Bible. And we do remember.”

The imperative remapped power dynamics within the Middle East in a way that was best evoked by a Black Cloud. The tribe of Amalek is not thought to have existed, but the current war is animated by a rhetoric foregrounding the divine punishment of Amalek “for what he did to the Israelites.” Th punishment has been long remembered, celebrated and recited as a collective truth in a scriptural narrative. It has become a terrifying topos justifying a war without borders, of visiting divine wrath. The pronouncement by Israeli Defense Forces “Hassan Nasrallah will no longer be able to terrorize the world” was not an understatement, but a justification of the totally overwhelming use of force. The increased equation of Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthi with this mythic tribe, allowing Netanyahu to lump these allies together, casts them as a war against Israel that must be waged as one of divine wrath, and a war that will be truly apocalyptic–that mirror Nasrallah’s own fiery rhetoric. Indeed, the repeated invocation of the Amalekites kept alive the memory of biblical destruction, leading up to the invasion of Gaza and the invasion of Lebanon, that offered something like an alternative orientation to a map, a model of describing the relation of the Jewish people to justice, and to escape the confines of international law–and indeed of nations. This is not a newly deployed future–Netanyahu compared the prospect of a nuclear Iran to Amalek before the US Congress in 2015, declaring that “the days when the Jewish people remained passive in the face of genocidal enemies are over”–even though the comparison to a ritualized memory of a biblical memory is absurd to modern geopolitics, and made Israel unlike any “normal” nation. Yet the “normalcy” of these operations depends on inherited narratives of scripture to motivate a military campaign without any clear endpoint of goal, that stands to consume the land.

The threat of failing to exterminate and destroy Amalek has redrawn the map of the Old Middle East in place of any rapprochement to Saudi Arabia in a New Middle East, which is now relegated to the past. This makes the invocation of the “Curse” that the Middle East faced out of keeping with the family of nations–or the participating of a council of “normal” nations, the United Nations–or hopes for peace among “a new Middle East, between Israel, Saudi Arabia and our other neighbors.” The a community of nations joined by a nation forged by shared memory of how it had come out of bondage, but been defined by a lineage and shared memory. The “Curse” lay outside of any nation’s history, and, via the invocation of a perhaps purely legendary people of the Amalekites was elided with the new shadowy non-state actors, identified as part of the “war against Amalek throughout the ages” that was waged by Jews. And Nasrallah’s refusal to cease waging war on Israel and fire on its northern regions until the end to all Israeli hostilities in the region of Gaza, a belief tied inseparably to his conviction that he was indeed shaped by having watched “what happened in Palestine, in the West Bank, in the Gaza Strip, in the Golan, in Sinai” and Israeli hostilities in Gaza. At the same time as the war has been pursued, in hopes some living hostages survive in the two hundred tunnels below Rafah, the slogan of global alertness–“All Eyes on Rafah”–calls attention to the dangers of residents of the city were Gaza’s 2.3 million civilians were forced to migrate–a social media counter-offensive, launched in parallel to Israel’s military offensive in early May if generated by AI and shared on Instagram and TikTok, of orderly rows of tents.

These hostilities have made that border war with Lebanon not about a Blue Line, or about Lebanon’s border with Israel, but about the persistent conflict of Palestine with an Israeli state. The attacks on Gaza increase the license of cross-border attacks on Israel, Nasrallah felt, justifying the lethality of the strikes independent from their legality, expanding a “balance of terror” to an axis of resistance.

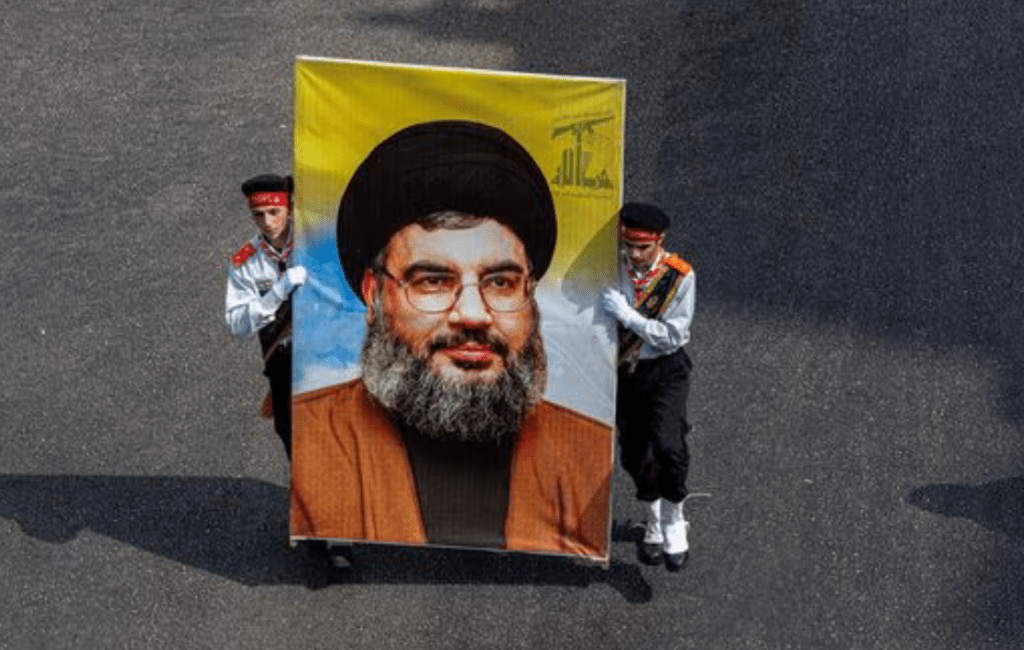

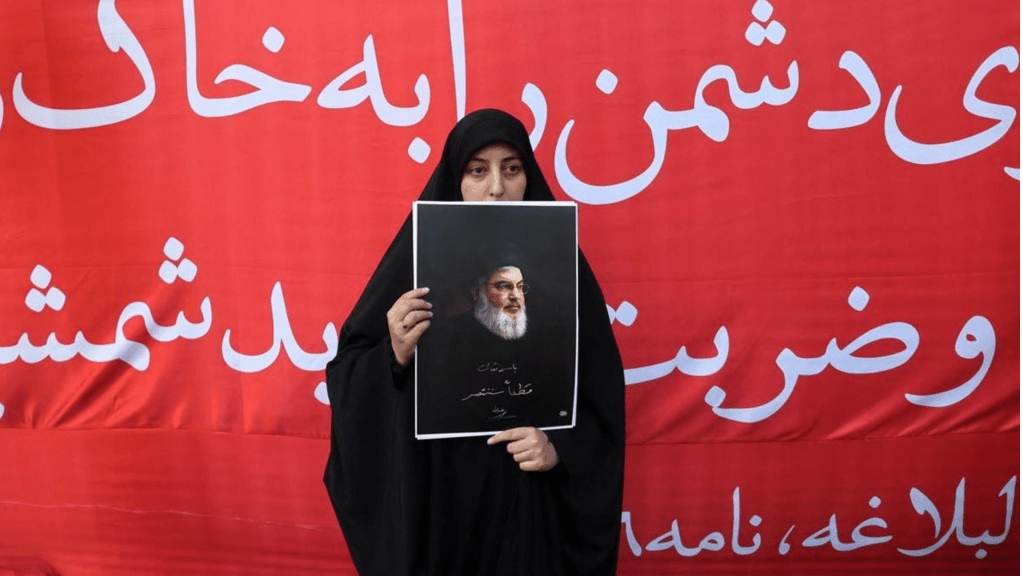

Nasrallah Preaching, circa 2014

The activation of the memory of the Amalekites provided a way to understand the need to visit destruction on the Amalekites as a way of living in the present. The ritualistic memory of the tribe who were hereditary enemies of the Israelites from the time of their arrival in Canaan elided the Palestinians–and Palestinian identity–with an ancient enemy of the ancient Israelites native to the Negev, dating from the era of Moses and Joshua, transporting audiences to pitched battles of an era of stateless wandering from a period before settlement in the Holy Land, who in Exodus had viciously attacked the Israelites at battles in the actual battlegrounds of the Sinai Peninsula, recalling the Mosaic altar inscribed with promise that “The Eternal will be at war with Amalek throughout the ages,” as if they were continuing a war of extermination internalized ritually, but was now transposed from a historical Canaan to a nationalistic notion of Israel’s frontiers: did the boundaries even have to exist or be drawn to continue the war that Amalek had himself advised other nations afraid to join him to join his initial push against their : “Come, and I shall advise you what to do. If they defeat me, you flee, and if not, come and help me against Israel.” Is not “war against Amalek [continued to be fought against the continuity of the deep rhytms of history] throughout ages?” The memories of these deep rhythms are preserved by telling, hearing, and repeating, but kept alive as a way of looking forward by looking back and–as Gabriel Josipovici observed of Jewish scripture–“by looking back only to help it move forward” in the “ritual recalling of what once happened” that is not historical or fixed in remote time, but an ongoing story, not motivated by looking back with nostalgia, but by demanding reform in the present.

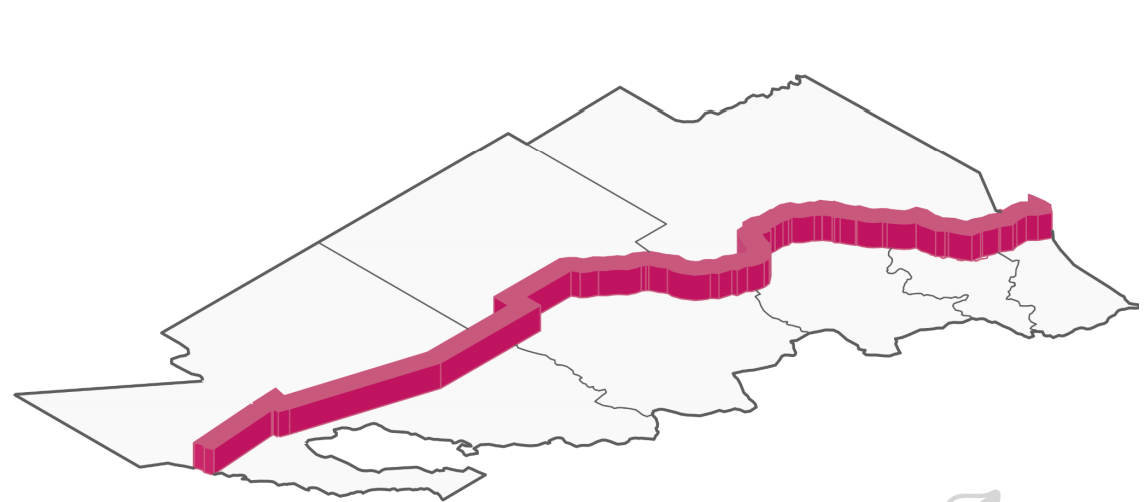

The jagged line of the current de fact division of the states was never an international boundary, but the conscious choice of Deuteronomic terms of vengeance and retribution of the current mission to “blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven” as one of eliminating attackers of the state of Israel–transform a war disputing boundaries to one of smiting those who staged an attack of viscious surprise on the Israeli people–erasing the long contested boundaries of northern Israel to an existential war at the heart of Judaism, devastating land, property, and border lines. The references are not only asserting a biblical right to territory, but a Jewish Holy war, mirroring the oratory of non-state actors as Hamas and Hezbollah, that stands in place of a language of nations.

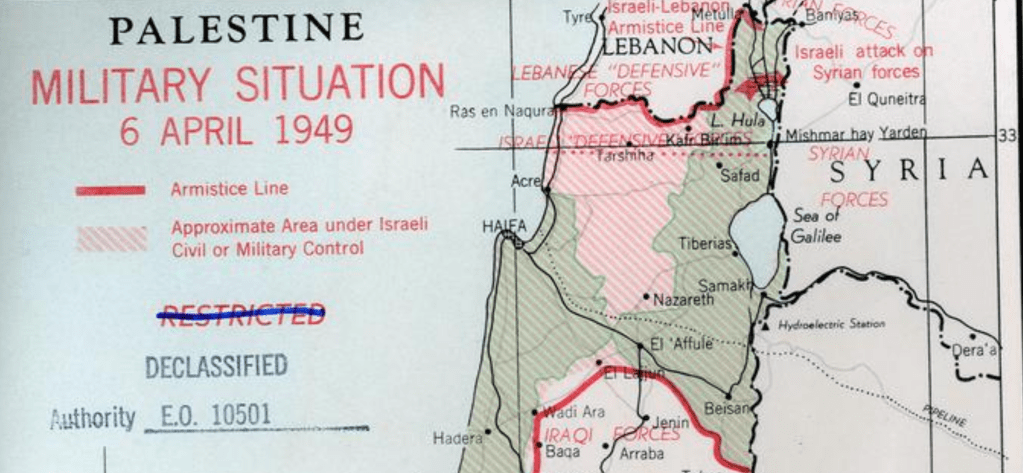

Israel-Lebanon De Facto Boundary Demarcation Line

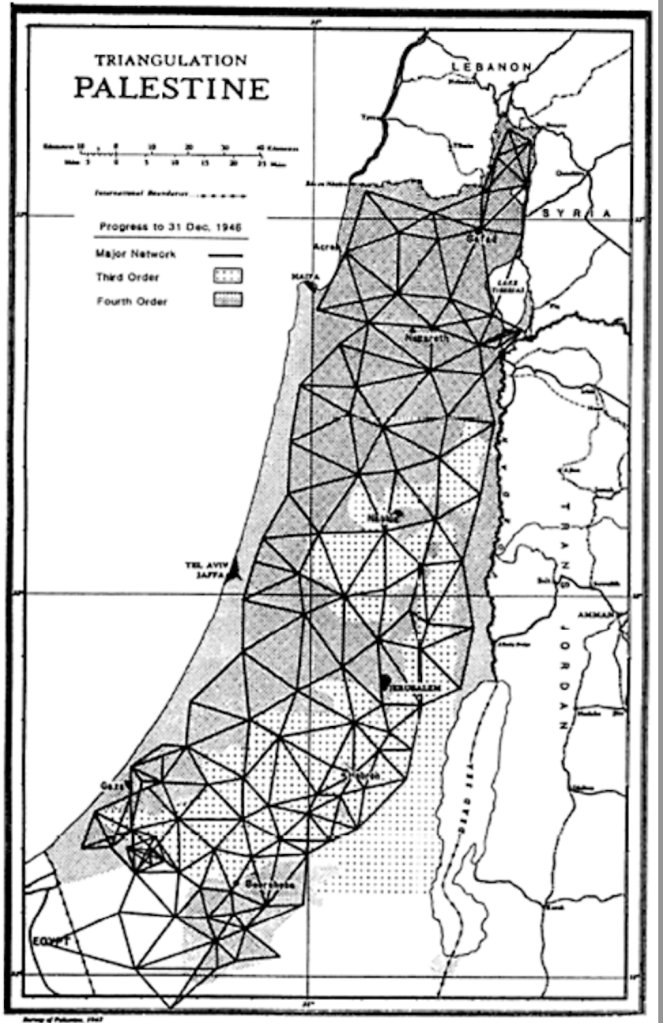

The boundary derived from triangulation of Palestine in 1948 that became the base map for the state of Israel–boundaries with Lebanon from the Mediterranean to cairns at Las-el-Nukurah, Khirbet Danian, Labuna, the edge of cultivated lands of the Waddi Kutayeh east to the Wadi Dalem as an armistice line, rather than an international boundary, to the villages of Ramia, Rita-al-Shaub, and valleys of Wadi Bediyeh, to villages of Tarun, El Malikiya and eastern village of Meis, Odessa, and Metallic or Metulla, the cairns of triangulation of the armistice line never intended as an international boundary than a line of withdrawal for Israel’s army, even in the Blue Line–a de facto line, provisional more than ever intended to conclusively resolve borders or boundary disputes. The mutation of a fixed line to security zones, and zones to be cleared of population, not only to meet the demands of Orthodox supporters of his own government, the language of biblical vengeance was supported by the invocation of the “horrific attacks of October 7,” attacks that were clearly intentionally designed to provoke the collective memories of panic of an actual holocaust–removed from any mere debate about “borders” and “boundaries” on a map. As Netanyahu used the narrative of “genocide” in terms of a revenge on the Amalek–“Go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have, and spare them not; but slay both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass“–as an existential threat, the armistice boundary of Lebanon was undone, erased and replaced by a devastation of a border zone.

The pseudo-scriptural injection to “eradicate this evil from the world” has been cast as for the benefit of American evangelicals or indeed for Orthodox allies, sanctioning his attacks on Gaza by the fact that “the Lord will have war with Amalek from generation to generation,” so much as a statement of the collective memory of Jews Palestinians would recognize and shudder. The projection of divine law offered a transcendence of the legal boundaries of Israel, unable to undermine or be in conflict with Israel’s longstanding aspiration to be a “normal” nation-state. If the triangulation of Palestine that preceded the State of Israel organized the mapping of temporary land settlements in a framework of organizing the territory in terms of its colonial administration, visualizing the temporary nature of divisions of land as a state of “permanent temporariness,” rather than of temporality. Indeed, the claims of naturalizing or institutionalizing boundaries present at the founding of the state of Israel are quite dramatically being undone and revised in the current remapping border zones of Southern Lebanon. While they may seem to be in terms of “Friend” and “Enemy”–the polarity of politics famously espoused by political theorist Carl Schmitt in the Nazi Era–the zones of evacuation, exclusion, and displacement are not about sovereignty, in a Schmittian sense at all: as much as a political theology, the intensity of such retributive strikes are Deuteronomic at core, if designed tto preserve the safety of an Israel. It is a logic of securing its borders to “blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven” per the Book of Deuteronomy, by visiting a retribution of such intensity and wrath that emulates the divine. The operations bring commands of remembrance–“Remember what the Amalekites did to you when you came out of Egypt . . .”–of scriptural origin to the modern day. Indeed, the figure this fictive tribe of Amalekites occupies in collective memory is an imprecation that today is akin to “Never forget . . .,” of deep resonance for the Jewish nation as a biblical collective memory from the very foundation of the Jewish people, no longer of a removed historical event but a living memory by virtue of its repetition as an ancient event bounded in space and time, that has become timeless.

If the injection is experienced as a bonding of God to his children as much as a leader to a nation, it has created a new logic of cross-border attack that demands to be appreciated outside the political. For as much as merely the recollection of a removed event of scriptures, the figure of Amalekites has become or been activated in contemporary Israeli political discourse and theology as a guide of living in the present; the call to “remember” becomes to learn how to remember becomes a way to “know” of a resonance that transcends political boundaries–even those confirmed in December, 1948, after the First Arab-Israeli War, at the Israeli Declaration of Independence that created the boundaries Israel shared with Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan. If those boundaries were created by a series of famous armistices signed with Egypt on February 24, with Jordan March 3, and with Lebanon on March 23, 1948, the last of which set a basis for military withdrawal at the “Blue Line” that led Israeli forces to withdraw from thirteen villages in Lebanon’s territory, on July 20, 1949, the armistice line that was agreed to in Northern Israel is no longer a line of armistice,–but has been cast in a different collective memory, no longer on paper maps or set stations of triangulation–

Israeli Delegation to 1949 Armistice Talks: Yehoshafat Harkabi, Aryeh Simon, Yigael Yadin, Yitzhk Rabin

Geodetic Triangulation of Palestine, 1946

–but by the logic ofan internalized narrative. The frontier nominally about a line of withdrawal enemy forces was, indeed, a basis to visit violence of a new level of complete destruction, and a new sort of enemy beyond the notion of a boundary dispute, and which challenged registers of mapping that reflected only on-the-ground damage: the level of damage inflicted over nine months and more of border fighting between the Israeli Defense Forces and armed Hezbollah forces in Lebanon goes beyond a border dispute, as the reference to the Amalekites tapped a collective memory of a litany of destruction that in fact knew no place, but was an almost timeless narrative not confined by space or time, a visiting of vengeance on a people who demanded divine punishment–“Now go and attack the Amalekites and completely destroy everything they have. Do not spare them. Kill men and women, infants and nursing babies,[1] oxen and sheep, camels and donkeys“–that was a divine judgement and not even a human one between nations or nation-states. This alone served to explain the non-state actors who attacked Israel–Hamas and Hezbollah–in ways that were foreign to a discourse of nations or a law of nations.

If the complex military situation on the ground was extremely contingent, and multinational in its composition of conflicting Syrian Iraqi, and Lebanese “Defensive” forces, the complex armistice line determined along the mountainous terrain of Southern Lebanon respected Israeli military control, if it was drawn along the line between Lebanon and Mandatory Palestine, with careful attention to Armistice Demarcation Lines that hinged on the control over mountainous terrain as much as permanent legal borders–at Arab insistence–but which would mutate into Israeli borders–refusing to recognize the boundaries as a settlement of the Palestine question in interim agreements that lead to the creation of demilitarized zones around many of Israel’s “borders” never leading to the signing of a peace treaty between Israel and Lebanon,–a problem of renewed relevance today.

Into this absence of clear cartographic rendered boundaries, and a stasis of military control led to deep resentment, the invocation of the shared memory of almost involuntary rather than voluntary recollection entered, echoing the imperatives to preserver memory and keep memory alive that may have been consciously invoked by the brutality of the invasion of October 6 by Hamas, but was a away to process the violence of the invasion. The tag “Amalekites” emerged as a counter-memory meriting the retribution on a biblical scale, invoking the Deuteronomic law of a lex talionis, not about the actual ancient landscape of the Middle East of Canaan–in which no proof has ever been found for the Amalekites–but an anathema-like demonization of a living threat to the Jewish people, tied to the deep political rhythms of their suffering and the affirmation of their primary and precedent tie to God–irrespective of who first inhabited the land of Canaan east of the Jordan, whether the Ammonites, Moabites, Edomites or Amalekites. For in the ritual recitation of Jewish belonging, it was the Amalekites who had joined the nations ion Moab and the Ammonites to attack the Israelite tribes, capturing “the city of palms” – perhaps Jericho or its pasture lands–(Judges, 3:12-13), and joined the Midianites in destroying the crops of farmlands they raided as desert tribes, before their decisive destruction, when Saul responded to the divine request to obliterate their memory by driving the nomadic tribe back close to the border of Egypt, reducing the influence of the Amalekites in the border regions of Judah and the Negev, back into the western Negev. The timelessness of a struggle against evil was a far more powerful lens to see the current war as a dichotomy between Good and Evil, removed from circumstances of dispossession of land, and far preceding the foundation of Israel in 1949.

This was a construction of the Palestinians in the modern Middle East as removed from actual problems of discrimination, an apartheid Israeli, or a dispossession of homes, but as an enemy to the Jewish state. The tag of the Palestinians as a tribal people of the desert–the “Amalekites”–were terrifying fighting words to designate Palestinians in Israeli politics. In national discourse, the evocation of Amalekites, even if the tribe is now thought never to have existed in Canaan, save in the scriptures as a people whose destruction was worthy of memory. The offense preserved in Deuteronomy and the Book of Samuel has become shorthand for acts of violence preserved in the collective narrative of Israel’s eternal memory; these original inhabitants of Canaan who terrorized the Jews. The Amalekites had occupied a figural if imaginary prominence as a threat preserved in collective memory of the Jewish people through Deuteronomy 25:17, a touchstone of calling to witness, and a call to witness in post-Holocaust Israel, a process of bearing that was deployed to process October 7 the violence of the attacks as an invasion meriting immediate retribution, and process events that intentionally triggered reflexive memory of the violence of a pogrom occurring on Israeli soil. The visiting of a ritual terror on the Israeli people merited a lex talionis akin to Amalek was not modern in any way, but confirmed the tribal nature of the peoples who had lived in Canaan before the Jews’ arrival out of Egypt. Both recent Israeli settlers and right-wing politicians have deployed the imagined tribe as a figure foreign to the world of “normal” nations, to conure an existential nemesis to be destroyed with a violence that did not belong to the world of normal nations, of divine proportions; the violence may stand in contradiction with Israel’s founding goal to be seen as a “normal” nation not unlike other nations from its 1948 founding, a steep problem of there constitution as if an exception of the ability to pursue geonocide.

The terrifying salience of the Amalekites in contemporary political discourse among settlers and Likud members is particularly striking, and suggests more than an audience to which Netanyahu played. Benzi Lieberman, Chairman of the Council on Settlements, invoked with zealousness the destruction of Palestinians by the boogeyman of Amalekites to map a people worthy of destruction–“The Palestinians are Amalek! We will destroy them. We won’t kill them all. But we will destroy their ability to think as a nation. We will destroy Palestinian nationalism.” Similarly, Likud activists used the equivalence to justify genocide: “Arabs engage in typical Amalek behavior,” a proclivity to evil resonating with the ritual retelling of scripture; if the prominent Likud activist was unable to “prove this genetically,” he recognized “behavior of Amalek” demands destruction, even a destruction as that visited on the Amalekites by God.

The reference to the Amalekites—who didn’t even exist!—offer the outlying example of acceptable conduct, even if it betrays the goal of being a “normal nation,” and casts Israel apart from normal nations, betraying its goal of being a normal nation—though what a normal nation is today is hard to know. “Torah commands the Israelites to wage an eternal war against the nation of Amalek, and to wipe them out totally,” reads the current website of Chabad, arguing that theAmalekites are no longer a foreign nation, but “an internal enemy” who “wage a lethal war with our soul,” and must accordingly be annihilated. “Amalek unfortunately and definitely exists,” and the South African legal team accusing Israel of genocide at th International Court of Justice quoted the commandment to “erase the memory of Amalek” to convict Netanyahu of having plans for genocide, but another face of Amalek is identified as forgetfulness, and the casting of the Amalekites as not fixed in time, but “internal enemies of the Jewish people” from he Nazis in the twentieth century to Hamas today suggests the demand to recognize the survival of the Amalekites, and “never forget'” what threats they continue to embody. The rather timeless opposition that Netanyahu invoked served as a way to cast the global threat as an existential threat, not tied to contingent circumstances or the dispossession of land, but only as a form of pure evil.

The diffusion of the future of speech in Israeli politics cannot be overlooked as a part of Netanyahu’s long game denying boundaries and borders. Over a decade ago, a member of the National Religious Party saw collective guilt of all Palestinians as “creatures who came out of the depths of darkness,” who “we will have to kill,” they characterized them as Amalekites–a people needing extermination. They are people who know no borders, who are not nations, and who have no place in the Middle East if Israel is to belong to a world of nations. When the remarks of Netanyahu were glossed by 1 Samuel 15 in the American media, a divine order to “destroy Amalek entirely,” the prime minister’s office insisted news agency clarify the exact citation of Netanyahu’s speech to the Book of Deuteronomy; if both passages reference elimination of a people, the Prime Minister’s office insisted the Deuteronomic origins clarified the logic by which these Amalekites were especially dark vicious non-state actors–whose extermination was demanded as they had no place in the world of nations, as it was entirely foreign to it, but a f tribe–even if there is no evidence for the tribe–save as a place-holder of collective imagination and collective memory. The Deuteronomic origins of the mandate for destruction was not to “blot out the memory of Amalek,” but to dispose of the creatures of darkness of the Amalekites by the logic of the Israelites penal code of the lex talionis of Deuteronomy 19:21, “life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot”–as a law of retaliation, and of protecting humans from every threat to their lives, the Old Testament principle, not a historical narrative of kingship, but precept for brutally visiting punishments on a people out of respect for the value of human life.

While the refenrce to the Amalekites was a potent signifier in right wing politics of a collective memory that offered tools of living in the present, the figure of speech was no doubt readily recognized by the Palestinians in Hamas and Hezbollah as a declaration of war that disrespected borders, a contradictory evocation of a license to kill–a declaration of genocidal intent to remove the “ability to think like nation”–a group that was likened to a tribe, rather than a nation. The characterization was a terrifying explanation for justifying failure of adherence to international norms by a nation, and, perhaps, the license to act as a nation outside of national norms. The new norms for visiting destruction on the Amalekites was not in the handbook of national norms, but was a script that mandated a total destruction of borders, indeed, and a reversal of the idea of the border to a border zone of safety of military creation, of evacuation zones from the Gaza Envelope to the border zone of Southern Lebanon, zones whose destructiveness with no similarity to borders.

The ceasefire lines between Lebanon and Israel, if long established, were in a sense negated by the assassinations, if they were already allowed to be contested in the expansion The assassinations of Nasrallah and two successors to his leadership–“Nasrallah himself and Nasrallah’s replacement, and the replacement of the replacement,” as Netanyahu crowed, sewed leadership chaos as a means to redraw Israel’s Northern border, even if it contravened international law. Netanyahu openly threatened Beirut stood at the abyss of “a long war that will lead to destruction and suffering like we see in Gaza,” on the anniversary of Hamas’ invasion of Israel, as four heavily armored divisions of Israeli troops filled southern Lebanon, destroying villages and burned thousands of hectares of farmland in Southern Lebanon, in a rewriting of the map that raised the specter that the nation no longer able to feed itself, seeking to destabilize the entire nation to pursue its ends of remapping the dynamics of power in the Middle East. Much as the Israeli Prime Minister hoped to “evacuate the whole Gaza Strip in coordination with the Egyptian government,” the hope of normalizing the expunging non-state actors from the future map of the Middle East was a “plan for the resettlement and humanitarian rehabilitation of the entire Arab population in the Gaza Strip which aligns well with the economic and geopolitical interests of Israel, Egypt, the USA, and Saudi Arabia,” remapping of national interests that expunged non-state actors from the map.

Netanyahu was addressing a press conference after addressing the General Assembly in New York, but the military planning of the assassination demand a reexamination of the maps Netanyahu had presented to the United Nations General Assembly–long involved in the negotiation of Lebanon’s southern border–and the maps by which we understand what was treated as a border conflict has become a map that expanded to what might be call a border zone, if not to create a demilitarized zone or a “dead zone” in ways far more literal and apocalyptic than the rhetoric of Nasrallah or Netanyahu had used. In arguing to Beirut’s residents “We’re not at war with you. We’re at war with Hezbollah, which has hijacked your country and threatens to destroy ours,” as meaning “Israel has no choice. … Israel must defeat Hezbollah,” the mushroom-cloud image of destruction that began in the evening and sent massive clouds smoldering sent a plume over Beirut in dawn hours and early morning rocked underground Beirut suburbs, demanded residents evacuate southern Beirut, blaming Lebanon for having allowed the transit of munitions from Iran to arrive in civil airports of Beirut, and continuing to target buildings housing munitions across southern Lebanon and Beirut.

September 27, 2024/Hassan Ammar/AP

The delayed reaction bombs entered the buildings to explode, creating a devastating if targeted damage by their pinpoint accuracy, striking Hezbollah commanders. Nasrallah had been tracked for twenty years, killing the head of Hezbollah, his successor, and close circle of commanders in an underground compound, is an illustration of frustration at inability to define the prolonged war at its borders. The strike across borders raised questions of violating international law, and of legal munitions, but eerily evoked a divine sort of justice.

The pinpoint strike at the circle it blamed for plotting attacks on Israel shifted the long war on its borders to an urbanized area: Nasrallah had angrily condemned how the planting of explosives on Hezbollah’s pagers and walkie-talkies for having “crossed all red lines,” and “broken all the rules,” as it had issued a virtual “declaration of war” by flying supersonic planes over Beirut, buzzing the headquarters of Nasrallah as if taking a reconnaissance flight over targets of later bombed. The final televised address he made condemned the aggression of the strikes airplanes made on Lebanon’s territory, coordinating a set of explosions across the entire nation of Lebanon, as if to alert the leader and of Hezbollah of the possibility of an Israeli strike at any site in Lebanon–a television appearance curious for how the Sayyed was instant on the bounds of Lebanon.

September 19, 2024

The the coordinated air attack that sent columns of smoke into the night air crossed those lines even more emphatically and spectacularly, revealing the precision mapping of the targets with a rather awesome if terrifying sophistication, suggesting a sort of divine wrath by dual guidance bombs that exploded eighty 2,000 lb bombs after they entered the four buildings, sending a fireball into the night sky, after residents were asked to evacuate all buildings that held “Hezbollah facilities and interests,” in a protocol of warning that has become standard to shield the civilians of the Gaza Strip and southern Lebanon.

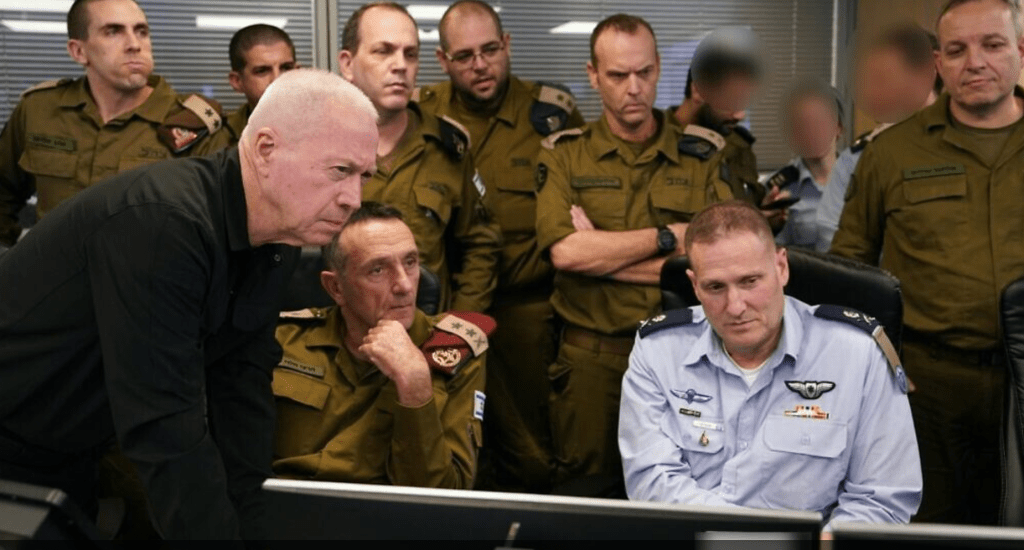

Defense Minister Yoav Gallant (left) and Chief of Staff Lt. General Halevi (center) watch the September 27, 2024 Attack in underground Israeli Air Force Command Center near Tel Aviv/Ariel Hermoni/Defense Ministry

But the strike that was monitored closely from Israeli Air Force Command Centers in Tel Aviv, show how the security of Israel’s borders knew no limits. The war begun as a defense of Israel’s boundaries was presented as neither in cities or Lebanese territory, but against the infiltration of Hezbollah, a non-state actor, deep underground in Lebanon.

Explosions over Southern Beirut of September 27 Bombing of Southern Beirut Spread over the City/AFP

President Joe Biden, an honest man, declared “his death from an Israeli airstrike . . . a measure of justice for his many victims, including Americans, Israelis, and Lebanese civilians,” the statement issued September 28, insisting he had no advance warning of the strike, but calling the death “welcome” even if it may well destabilize the region. While his Defense Secretary had spoken with Israeli allies about using the bunker busters only as the operation had begun and was already underway, Israeli official described Netanyahu’s address of the UN General Assembly amidst escalating fighting with Hezbollah in Southern Lebanon as a ploy and “part of a diversion” to lull Hassan Nasrallah into believing in his safety, the open rejection of any hope for diplomatic resolution of the ongoing border conflict ramped into new gear as the aim was revealed “for threats to Israel to be removed.”

Bombed Compound in Beirut Suburb, Dahiyeh, September 28, 2024/AFP

The assassination, timed after multiple unsuccessful attempts to locate the hostages of August 7 or protect its victims from attack, was based on tracking the senior chain of command of attacks on Israeli citizens, as if dropping at least sixty bunker buster bombs equipped with precision guidance systems–bunker-busters able to penetrate deep underground and flatten built structures–killing Nasrallah and much Hezbollah elite was a just strike. Nasrallah had been long targeted by Israeli forces, after being tracked by radioactive material placed on his palm in a friendly handshake, ageolocation of a man long underground was able to offer inside intelligence. Ten days after a spate of terrifying explosion of thousands of pagers booby trapped with explosives across Lebanon in the hands of Hezbollah commanders on September 17, and walkie-talkies on the following day, had compelled a meeting of commanders, the strike in Beirut’s suburbs revealed terrifying vulnerability of once-secure borders. The border treaties suddenly destabilized with the jackpot of killing believed the senior chain of command planning “terrorist activities against the citizens of Israel” as if to legalize the strike, by preemptively eroding the borders of a zone of conflict across Lebanon.

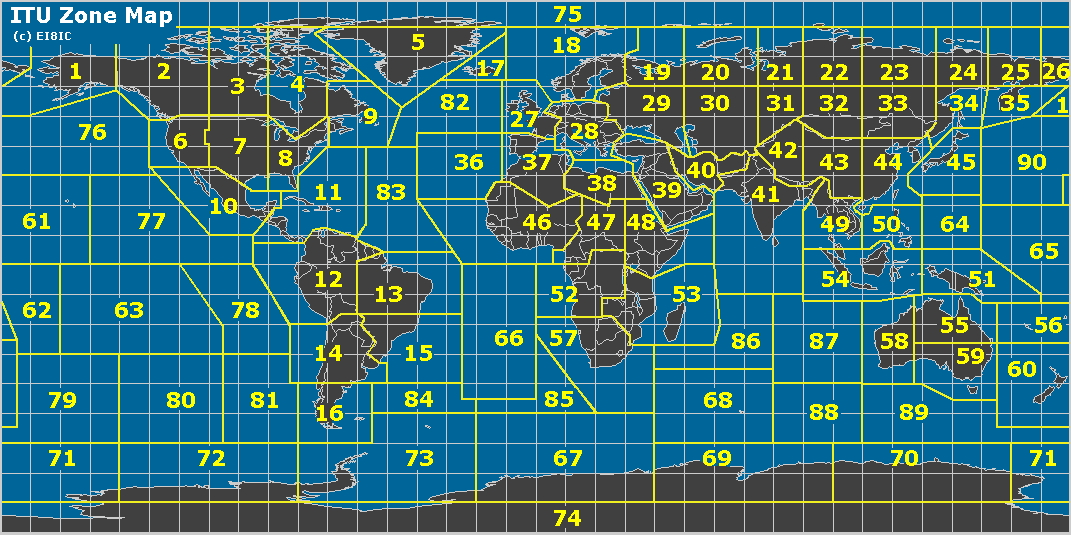

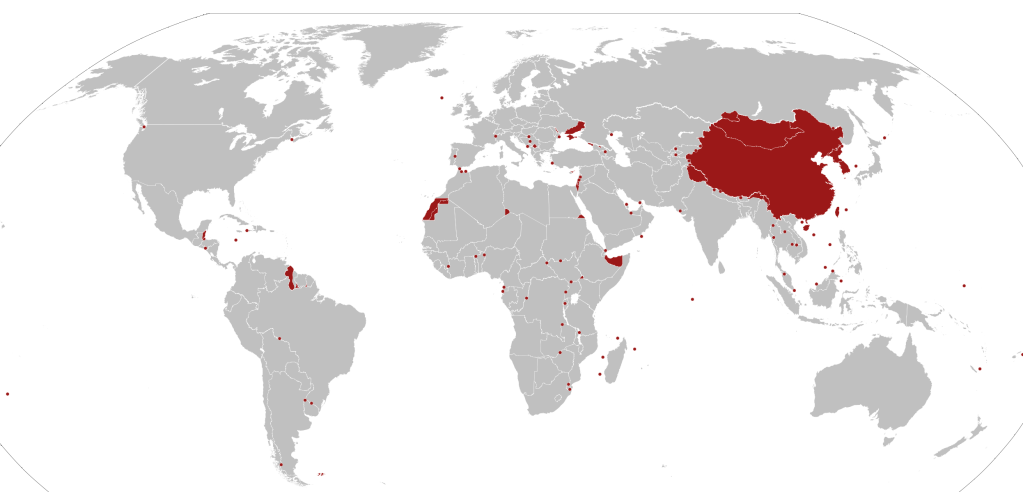

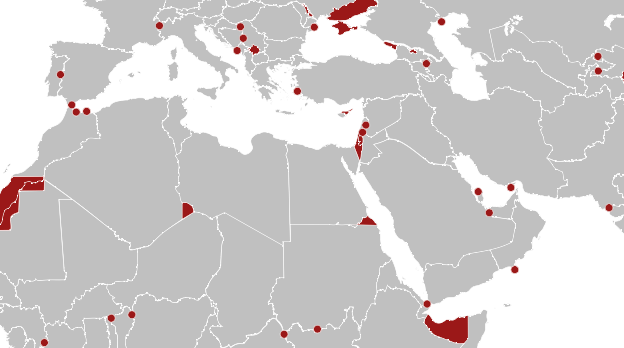

Borders were the center of Nasrallah’s active engagement in the military, defending Lebanon as a frontier. Nasrallah had long claimed the resistance of the “oppressed people of Palestine” would triumph even over a nuclear powered Israeli army, preached the power of on the ground resistance to any military force. And the explosion of pagers on Lebanon’s territory violated “all red lines” in its brazen violation of the integrity of territoriality, the arrival of bunker busters in a residential neighborhood suggested even more completely the absence of respect for sovereign lines. Indeed, if the disputed borders in the world of territorial disputes are widely spread–

Territorial Disputes in the World, 2024

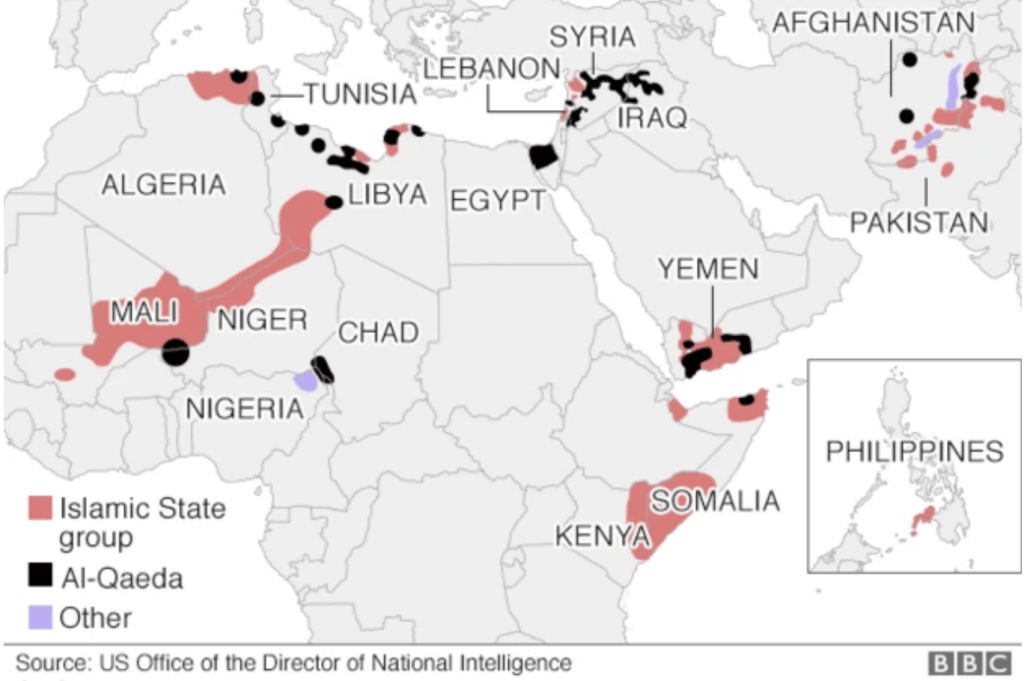

–the focus of territorial disputes in the Middle East were intensely linked, with firing cross-border rockets from Lebanon as the Gaza War began, or after the Al Aqsa invasion, and the rockets of reprisal Israel fired at underground tunnels for assembling rocket launchers in southern Lebanon.

Territorial Disputes in Mediterranean Theater and Middle East, 2024

The intensity of arial bombs that were three times the force as used in the Iraq War suggested a massive show of force. Yet the long disputed border in which Nasrallah had essentially dedicated his life–inviting Iranian arms into the longstanding dispute on the border with Israel, daring Israeli forces to enter Lebanon or Lebanese lands, seeing each village as the basis for defying Israeli arms, after having expelled Israeli forces from southern Lebanon in 2000, while wearing the black turban of a Sayyed, or descendant of Mohammed, had declared the imminent arrival of a moment of reckoning, had avoided assassination for more than a decade, but the onslaught of precision bombs offered a near-apocalyptic ending for his life, as much as a precision strike.

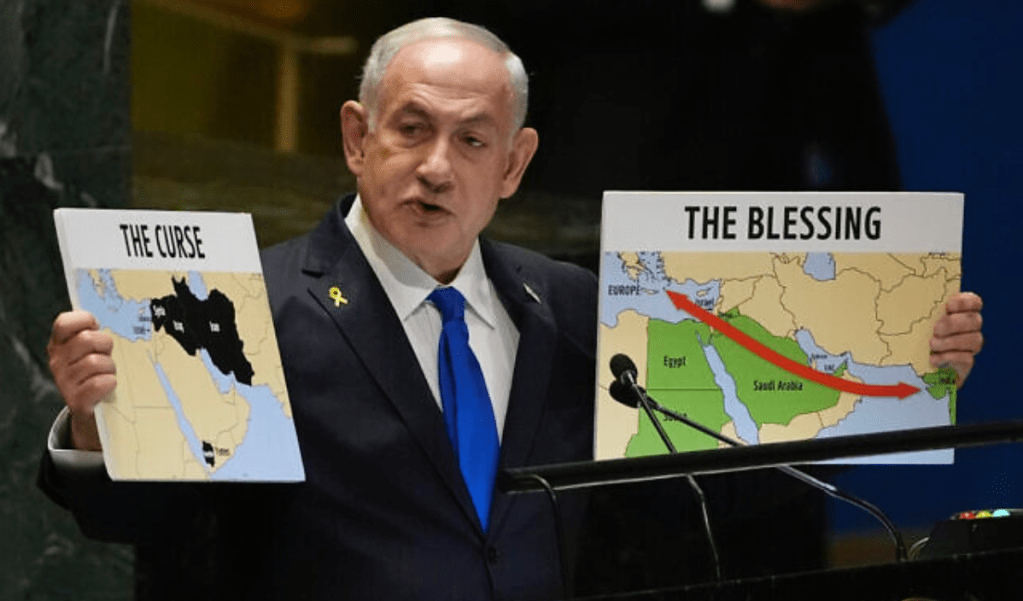

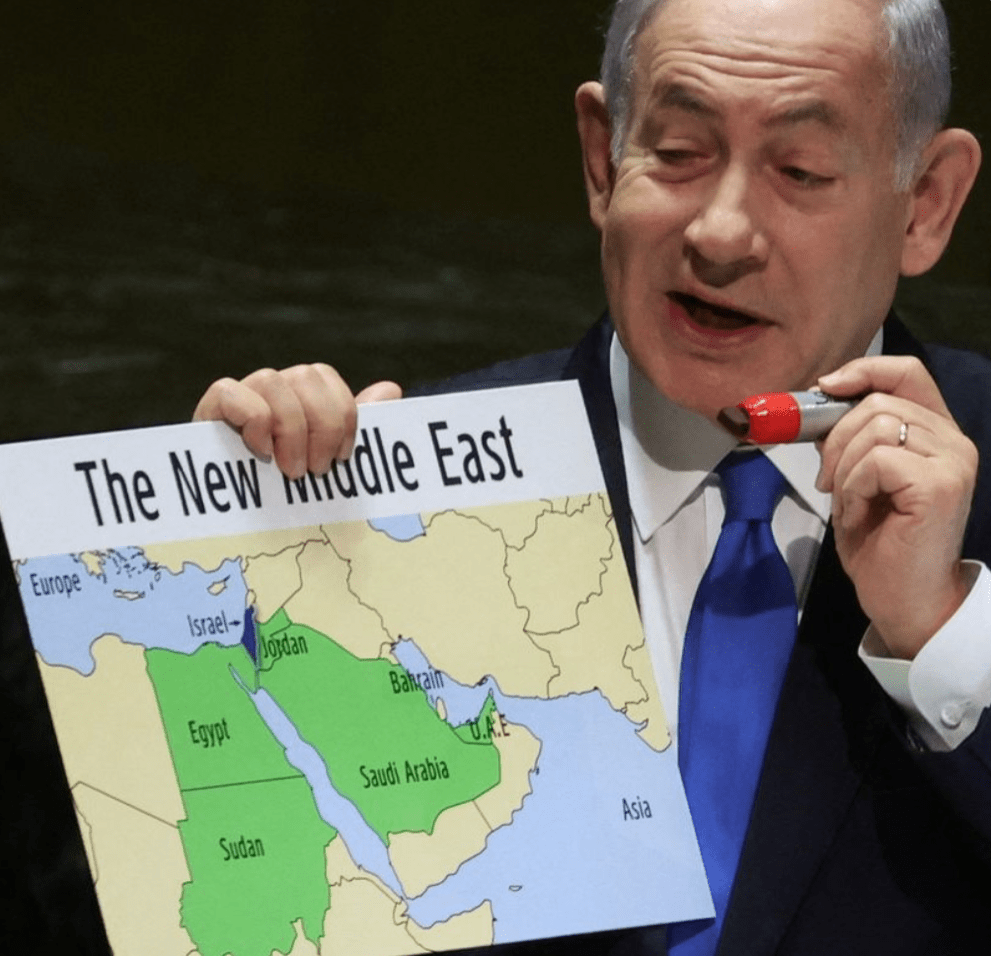

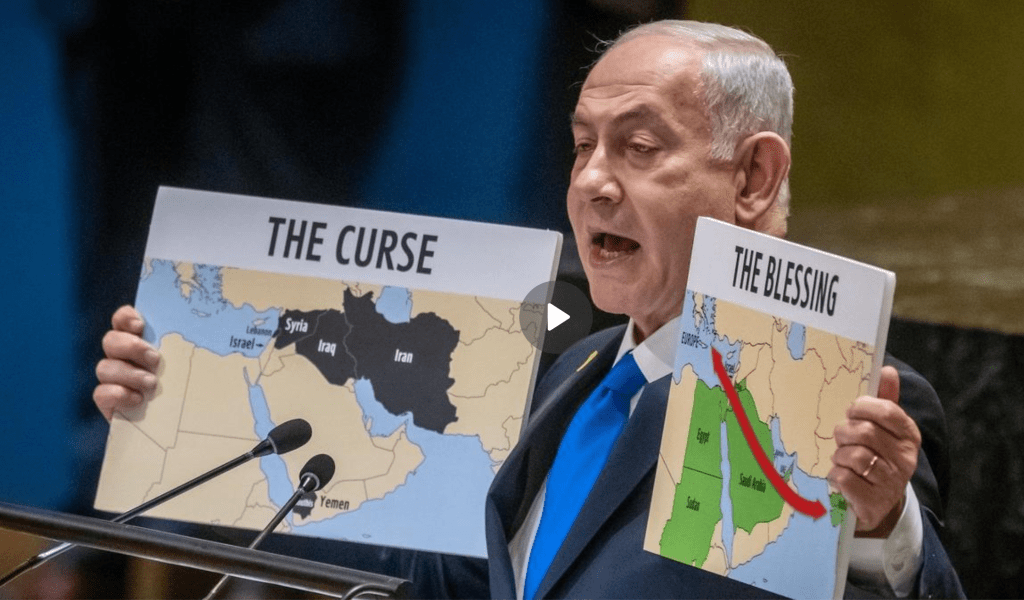

Americans might wonder at the use of bombs of this strength in an urban area. The strike targeted the rapid expansion of rockets supplied by Iran to arm Hezbollah–estimated with 150,000 missiles, drones, and rockets, over ten-fold what it possessed at the end of the 2006 war. The current explosion matched attempts to stop the smuggling arms to Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen–a black cloud hovering above the region that Benjamin Netanyahu, having approved the massive strike, showed the UN as “The Curse” of the modern Middle East. While “A few years ago, I stood here with a red marker to show the curse, a great curse, the curse of a nuclear Iran,” the return of “The Curse” on the eve of the assassination of Nusrallah seemed a cause for celebration. In a sense, the map was a smoke screen and distraction from the invasion of Lebanon’s frontier, ignoring national sovereignty and laws of sending bunker-busters in inhabited areas or military targets near them: but the “lumping” of nations opposed to Israel’s borders–Iran, Iraq, Syria, and the Houthi non-state–as if it was the mushroom cloud portentously spreading above the entire Middle East–

Map Displayed to U.N. General Assembly, September 27, 2024

–that his precision strike hoped to end. The map masked how the bombing was a transgression of international norms. Israel had undertaken in targeting the leader of Hezbollah for three decades, but finally did so in ways Netanyahu seemed to offer an explanation, if one that was not logical in any way. “The Curse” evoked a Neo-scriptural justification of the precision strike already planned against Nusrallah and underway, as pinpoint bunker-busters had left to strike at a link at the heart of the black cloud hovering over the Middle East–Iran’s man in Lebanon, who had been firing rockets across the northern border of Israel with considerable annoyance over the past year.

Sick of the involvement of Iran in non-state actors in the Middle East, the Prime Minister ended his press conference in New York quite abruptly as he was informed the strikes had been achieved, not taking any questions. The massive show of force intensified cross-border rocket attacks at northern Israel and reprisals preceding Nasrallah’s assassination blurred a border drawn on the ground, relegated to a relic of the past. To affirm the integrity of Israel’s borders, the planes flouted the sovereign space of Lebanon, at great costs to seeing Israel as a “normal” nation among nations, sending a two thousand pound bunker-buster bomb agains the man they had tracked for years, but now claimed, using a word that had its Old English origins before 1150 to cast an anathema on the forces of non-state actors that threatened Israel’s borders, and in his eyes threatened a global order: if the map was more of a news map, a backdrop of a television news show of the 1990s rather than a map of any granular resonance,–or that reflected actual mapping technologies the Israeli Air Force was using at the very same time to kill Nasrallah asNetanyahu finished his address.

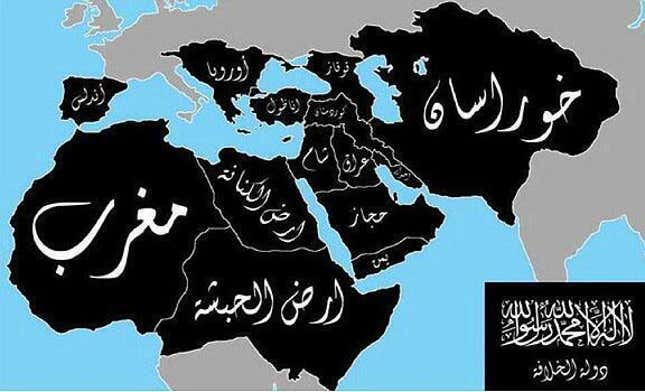

The map conjured the scale of an anathema that existed in the present more associated with the occult or medieval origins–if recently revived in Harry Potter–to conjure excommunication from the world of nations, or the church, the opposite of a blessing of a future of peace. Was there not an intentional similarity of this dark map of the Iranian state’s infiltration of non-state actors to the remapping of the Middle East in maps that circulated online a decade earlier, in 2014, allegedly depicting the world domination sought by ISIS, a mashup of earlier maps, as a curse, to evoke a perspective restoration of a Caliphate that might bridge Iraq, Syria, and Iran, up to Vienna? The map emerged online, an emblem of fear paired with the change of ISIS’ name to “the Islamic State,” and pronounced its leader to be the caliph, or the global leader of Islam–and seems a projection (so to speak!) of the fears of an actual caliphate bent on global conquest–as a pseudo-Stalinist “Five Year Plan” that seemed to broker a resurrection of an early modern version of a global Cold War–“a chilling plan for global domination” per the Daily Mail–was the original image of a global threat.

Although the purported “five year plan” of the Islamic State made runs as “showing their plans for the next five years” on American television networks, eager to find a new image of global divides–

False Mashup of Islamic Hopes for a New Caliphate, Twitter circa July, 2014

–themashup of online extremists, based on a hundred year old map of an imagined Caliphate, was an old recycled map, rather than designs for global domination. If versions included India and Bangladesh for good measure as a counterweight to Europe, it sought to conjure fears of barbarians at the gates of Europe, a sort of expansive vision of a Fall of Constantinople to barbarian hordes, to which Netanyahu’s September 2024 map of the “The Curse” made some weird reference. This was the global threat that the bombing of Beirut was serving to puncture or thwart.

Maps stoking fears of the spread of Sunni extremism were amped as the Islamic State as a miasma spread across an expanded Middle East, destabilizing the post-Cold War New World Order with a near global reach. The specter stood behind the map Netanyahu brought on September 27, 2024 was itself a massive exaggeration of the fragmented pockets of Sunni terrorism, per the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence, yet the cartographic mashup activated a potent emblem of fear, circulating quite widely as a haunting of the Middle East that seemed destined to spread to the EU.

1. When Netanyahu claimed that Hezbollah–and Iran–constituted a global threat “able to terrorize the world,” he was magnifying his own perspective on the world, and elevating the strike of Israel’s Air Force to a global intervention of its own. The strike was a bonanza in geolocation, a payload that seemed a jackpot against Hezbollah after a year of deepest frustration. After Nasrallah had charged Israel “violated all red lines”–not only the so-called “blue line” that marked the border of Lebanon since 1948–as it blew past the militarized borders in an unprecedented firepower claiming legitimacy, as if visiting a divine judgment on a man who has long preached the destruction of Israel in Messianic terms. It revisited the apocalyptic rhetoric of Nasrallah on himself and his inner circle, as if to reclaim a rhetoric of divine judgment and wrath at the violation of Israel’s borders.

Banner of Nasrallah’s Turbaned Head Held on Religious Procession in Beirut, July 2023

Mourner of Nasrallah’s Death in Iran

Yet the Prime Minister who ordered the bombing tried to make the case of its necessity, even if it removed Israel from ceasefire or peace process. In contrast to the regional the maps Netanyahu had displaced before of Israeli frontiers, he bought a map of an expanded Middle East to the United Nations of alternative future geopolitical scenarios, Israel’s incursions of the border to “limited, localized, and targeted ground raids” against Hezbollah in southern Lebanon, the tonnes of bombs seemed to se disarray in a “militant infrastructure” of Hezbollah on the eve of the first invasion of Lebanon’s border for eighteen years. The presence of Hezbollah among residential areas–per Netanyahu, in late September 2024, “a missile in every kitchen, a rocket in every garage” merited returning Lebanon, per Yoav Gallant, “back into the Stone Age,” in June, 2024, if a diplomatic solution does not present itself. As journalists are for the first time invited into Southern Lebanon, to witness the degradation of Hezbollah in villages across the border, achieved by airstrikes, artillery and raids, the invasion past UN demarcation lines revealed weapons caches, Kalashnikov rifles, artillery, hand grenades, and mortar shells, designed to stage an invasion of Israel, to disable all remaining offensive capacities of the terror group by the end of the first weeks of October, 2024.

But the IDF had already made its presence known. If the walkie talkie and pagers exploded to injure faces and arms of many, the attempt to cut off the head of Hezbollah was designed to send shocks across the system. The sudden shock of pagers long used as they were believed possible to avoid geolocation in their lack of sensors seemed a magic trick of sorts: “we are everywhere, and we can strike you anywhere,” able to strike in the web of the secret militant organization under Nasrallah’s eyes, troubling his sense of control. He did not know that he had been tracked for some time–a trackable substance being placed on his palm in a handshake in Iran or Saudi Arabia or Beirut, per Saudi news, placing him in the building complex.

Deep underground beneath an anonymous apartment complex outside Beirut, the long-hidden Nasrallah, nemesis of the Israeli state determined to undermine the Peace Process for three decades, was as vulnerable as a sitting duck by a massive explosion–unable to hide longer. His death at sixty-four cut short a fiery leader of thirty years, offering stunning confirmation soon following Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s declaration of what seems an ultimatum to the United Nation’s, not revealing or tipping his hand about operations that were by then already underway, “We will not accept a terror army perched on our northern border able to perpetrate another Oct 7-style massacre.” The “limited” operation seems a way of expanding an occupation of the region Hezbollah has long worked and based its infrastructure of rockets and missile launchers from the south of Lebanon, as it has attempted almost forty years ago to root out the Palestine Liberation Organization from Lebanon in 1982.

The explosions of low-tech pagers and walkie-talkies did not rely on geolocating sensors–but revealed the hidden reach of Israeli Defense Forces into the organization. Panicked at hearing rumors and buzz of an attack, Nasrallah instructed Hezbollah members to rid themselves of phones, bury them or put them in lock boxes, back in February as compromised–“I tell you that the phone in your hands, in your wife’s hands, and in your children’s hands is the [compromised] agent.” He had heard rumors on intelligence lines for the planning of the attack that would render his forces vulnerable in new ways. The operation had been planned for over twenty years, the result of outrage at the border war. Nusrallah had concealed himself for eighteen years, shunning public appearances since 2006 war, aware he was targeted, was a victory of mapping, as much as inside informants. The blast of eighty tons of bombs that followed in quite dramatic fashion based on real-time intelligence triangulated a quarry long sought in a dramatic blast of thunder from above. The Hezbollah leader had been shaped by the Israeli invasions of Lebanon, religiously trained in a Shia mosque in Iraq, combined liberation theology and apocalyptic imagery to articulate a charismatic vision of the struggle non-state actors suited to wage against Israel in his customary black turban and brown robe. After remote assassination by cel of a Hamas bomb-maker in 1996, he grew rightly wary of remote devices able as keys revealing the location of soldiers, in danger of lifting a needed veil of institutional secrecy to his enemy. The planting of timed explosives in walkie-talkies and pagers evaded his justified suspicions of mobile networks, but penetrated deeply into his infrastructure.

Reported Locations of Surprise Explosion of Pagers and Walkie Talkies across Lebanon, September 16-17, 2024

The shock of the exploding pagers staged a cross-border assault of brazen intrusion and infiltration that suggested the intensity of the war no longer about the contested border of Lebanon, or the range of Hezbollah in Lebanon, but the open wide nature of war.

Indeed, these exploding pagers were but the prelude to a new state in cross-border infiltration and attack, a long designed operation of which the supply chain infiltration in pagers–in which explosives were inserted as they waiting to be shipped to Lebanon–was the first escalation of cross-border strikes. The strikes that maimed some 1,500 fighters from September 17-18 set the stage for the bombing of the complex in which Nasrallah summit had called a device-free summit in Beirut, to plan future attacks against Israel, to open a needed window in which Hezbollah’s arsenal might be strategically dismantled in Lebanon. Overriding desire to find hidden underground leaders of Hezbollah and Hamas across jurisdictional borders has prioritized problems of cross-border tracking as well as of evasion.

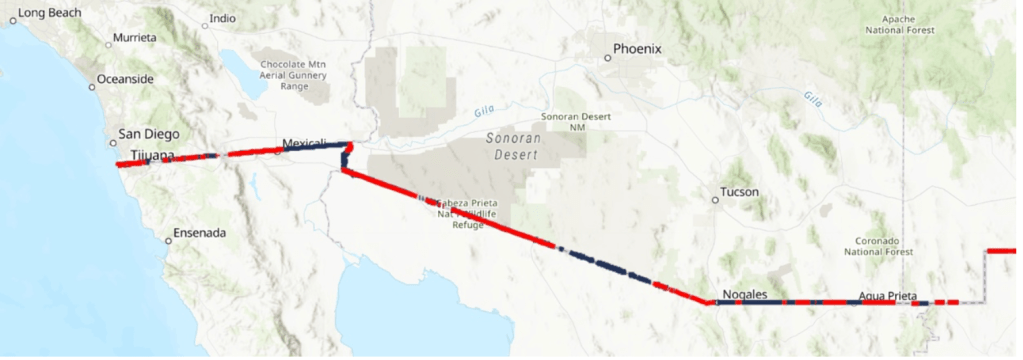

The increased sophistication of strategic tracking became paramount in ways that cannot be explained by the boundaries of the Middle East and the Israeli state since its founding in 1948, even if Israel’s boundaries are defended as having the authority and legitimacy of a scriptural covenant. With boundaries this intensely in need of defense and guarding, how can Israel be a normal nation, or a nation like all other nations, when it is dependent on firm borders to exist? Are the barriers that were built around Israel–and the concrete barrier along the “Blue Line” of withdrawal in the north, the divide from Lebanon, a sign of strength to be defended, or of weakness, isolating the nation from its neighbors, even if the hope is to live peaceably with them? Is not the northern border with Lebanon, more than the border of Gaza across which Hamas charged on October 7, the more dangerous border on which IDF forces have focussed in the previous decade? The completion of the barrier of border fences that were completed by the one hundred and fifty mile frontier fence between the Sinai and Negev deserts in the south of Israel, leaving only the barrier between Jordan and the Dead Sea without a physical border barrier, were claimed necessary deterrents against terrorism, complete with the thirty-two mile barrier with Gaza that Hamas insurgents pierced on October 7, 2023, including the new wall planned around Metullah in the north.

Border Barriers Constructed around Israel, 2012

The maps that Netanyahu brought to the United Nations General Assembly as the attack on booby-trapped walkie talkies and pager was underway was crude, if to the point–not of nations, or of states, but of “The Curse” that had afflicted his nation–as if to conceal this was a war of stateless–positing the true dark nemesis that was the “curse” of dark forces that threatened Israel’s existence and had in fact animated the distraction–absent from this map–of the Gaza War–there was no Gaza, no Palestine, no West Bank, but a true menacing black cloud without “true” borders. The black expanse almost surrounding Israel is identified only as an anathema–“The Curse”–to suggest what has been mapped predominantly as an issue of territorial jurisdiction is a spiritual, temporal, and even existential evil. Challenging his audience to open the “black box” of threats Israel faces is perhaps the only way to appreciate the operations already in the process of being launched into Lebanon’s sovereign capital, as four planes bearing bunker blaster that would soon be on their way to bomb apartment complexes in Beirut.

The dropping of a hundred “munitions,” dropped by bombers over Beirut every two seconds in a stunning precision, erased any trace of the commanders of Hezbollah in ways that were hoped to clear the board to remake the map of the Middle East and northern Israel, yet again. The black cloud of accursed enemies of Israel–Syria, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, and the Houthis–were not only the sources of increased missiles attacks on Israel,–was shown as a transnational alliance, intimating if not mapping the constellation of state, semi-state, and non-state actors supported by Iran as a destabilizing agent of regional instability, united with allies, as the audience of nations of the General Assembly understood, to undermine the presence of the United States influence and indeed a UN presence in the Middle East.

Netanyahu Addresses the United Nations General Assembly, September 27, 2024

The black transnational “curse” stretching from Lebanon to Iran exposed an unconventional alliance hardly in need of mapping. It made the link implicit in the vengeance strike that would arrive later the next day in Beirut as a strike of vengeance akin to of a deity, although he didn’t say so. As if announcing the traditional role of an ancient king of Israel to “break the power of the wicked,” by the state prerogatives of defense akin more to a Law of Kings of Israel than grasped by the law of sovereign states. This ruler of the state stands in place of the king. Indeed, as the message of Samuel to Saul, Israel’s king, that he punish the Amalekites for “what they did in opposition the Israelites when they came up out of Egypt” to the land of Canaan, that lead Saul to “utterly destroy all the people with the edge of the sword” [1 Samuel 15.8] in a central “genocide narrative” in which the Israelites received the divine sanction to wipe out an entire people by a “holy war” over a sacred space, not necessarily believing or even lending credence to biblical legend but ramping up the shows of force against non-state actors to a level historical inevitability of the acceptance of the unending presence of a state of Israel in the Middle East. Rather than occupying merely a story of the legends of ancient tribal heroes–Samuel or Saul–the Book of Judges–that suggest a story of the regaining of the spiritual destiny of the Jewish people, the origins of the legend of the Amalekites that Netanyahu’s office reminded American press agencies belonged to Dueteronomy, the sacred and most deep-lying legal codes of the Jewish people, from a time of their deep tie to God, rather than the Babylonian period or Roman period or a lamentational prayers to God as a righteous judge.

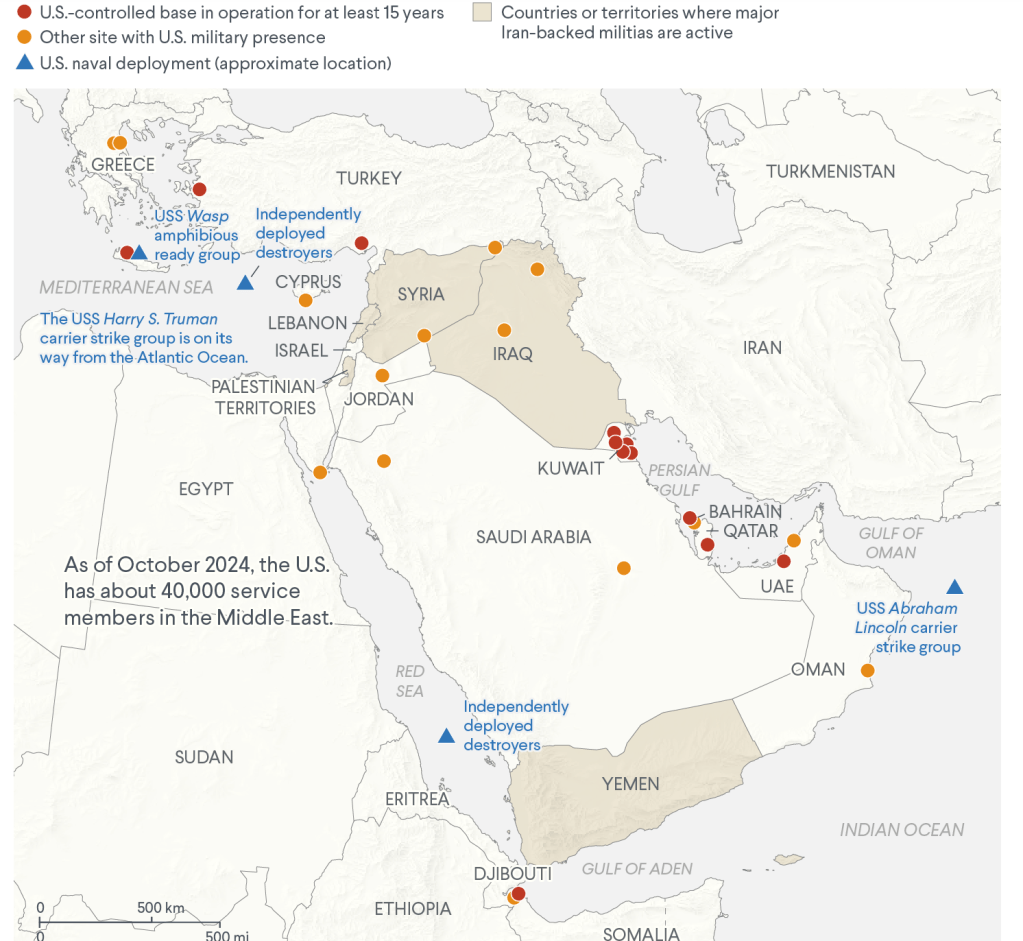

The maps Netanyahu carried to the United Nations was not a map of boundaries, but a haunting of the Middle East with anathema. The ongoing presence of a malignant “curse” of proxies was a continuation of the Amalekites, in some sense; it helped to make the state of Israel difficult to see as a normal state, as it could not be understood by a map of boundaries and their defense: the map of the black blot that spread as a dark cloud across the Middle East from Iran, even if this was not identified, was paired duo with “The Blessing,” as a theological or exegetical map, masking as a geopolitical map. It invited member-states of the General Assembly to take sides while they still could, in order to stop gathering clouds of an end to peace sponsoring terrorist organizations dedicated to Israel’s distruction. The map Netanyahu presented to the UN General Assembly, after he had given the go-ahead to the bombing of the bunker where the Hezbollah leader was sequestered. This killing might dismantle the anti-Israeli Axis of Resistance, Netanyahu hoped, diminishing anti-Israeli forces in the region and ending the threat to his northern border. It was a map that was not designed for American audiences in particular, but its display, combined with news of the assassination in progr4ss, led increasing American forces to be stationed in the Middle East, as ceasefire negotiations continued, was a smokescreen to the incursions of Lebanon’s border.

Arrival of Amp[lified United States Strike Groups in the Middle East, October 1 2024

These new forces were off the map, a bit jarringly, as Netanyahu somewhat blandly compared the options for the community of nations in his address to an almost empty chamber in New York on a late Friday afternoon. Speaking five days into the launch of the attacks across the northern border into Lebanon, the map of the Middle East was a blunt refusal to recognize international pressure for a ceasefire, and a refusal of the two-state solution establishing Palestine as a “normal” nation, as the Israeli Defense Forces were given the directive to “continue fighting at full force” to protect its borders amidst a map of such looming existential threats.

The paired maps offered a rhetorical smokescreen, a counter-map to the question of the conflict on Lebanon’s southern border, on the eve airplanes were sent over Beirut’s night skies drop bunker-busters that would kill Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s leader, and justify the pummeling of cross-border attacks on residential communities in southern Lebanon, where Israel has argued Hezbollah is entrenched as a proxy for Iran. The map was launched in response to Hezbollah’s cross-border attacks to protest the invasion of Gaza, but the map Netanyahu brought to the General Assembly this year neither showed Gaza or the West Bank or military operations of that invasion. The speech was not performative, but a stubborn tenacity to a map that might later be understood to justify the hope that a planned ground invasion of Lebanon would reconfigure the map of the Middle East in the long run. It was a smokescreen not to look closely at Lebanon’s border–or a summons of a sort of shadow-diplomacy to send quickly more American reinforcements to the Middle East.

Netanyahu had given approval to the assassination of Nusrallah with bunker-buster bombs shortly before he addressed the United Nations on September 27, and his use of maps as visual aids in a speech that commanded less attention than his previous addresses of the General Assembly can be seen only in the context of the surgical strike he knew already underway half way across the world.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu Addresses United Nations General Assembly/September 27, 2024

Netanyahu set the map of “The Cures” off against an alternative vision of a far rosier sense of the future, the map of “The Curse” rhetorically presented, as if diverging roads in a wood, a stark choice of the world between alliances, as if a compare and contrast question for High School art history. The black block of nations that were seen as agents of Iran perhaps addressed an Israeli public as a message of resolve, and in part addressing Iran, with the declaration that, with attacks of increased firepower in Lebanon underway, that the crude superficial maps depicted a reality that “There is no place in Iran that the long arm of Israel cannot reach, and that’s true of the entire Middle East.” There was of course no monopoly that Netanyahu had on apocalyptic visions–they were central to Nasrallah’s oratory and his own political thought, if it can be called that, and his motivational calls for the role of Hezbollah in the Middle East as an agent of destruction.

But it was also a map for the American public and an attempt to rebuff the possibility of negotiation or a ceasefire in a war that was fundamentally for the world’s future. The global map of Manicahean alternatives was a map of theological dimensions, delivering two ways Israel could be integrated in the community of nations. The pressing importance of the potential constellation of alliances between Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and India illustrated a de facto annexation of Gaza and the West Bank as if this were the starting point of negotiations, and the reality that Iran was isolated and contained as a nuclear power by the alliances he showed in green. But if the map of “The Curse” of the current geopolitical landscape that Israel faced in the Middle East, it hardly presented Israel as a normal state; far from it, the rhetoric of vengeance of the current map threaten to recast it as a a pariah state. Although the mapper maps projected the deep isolation Israel felt. It failed in its attempt to visually communicate the pressing urgency Netanyahu (and Israel) both felt at the need to act alone, even in the face of the broad condemnation of Israel’s invasion of Palestinian lands in the Gaza War as the air raids on Beirut unfolded. Perhaps the shift from the map of Israel secure behind borders in a “new Middle East” Netanyahu held up in 2023 before the General Assembly,–offering no mention of Lebanon, as a new regional alignment just before the October 7 invasion–

Map Netanyahu Displayed to the UN General Assembly of “The New Middle East,” September 22, 2023

–secure behind the barriers constructed to defend its borders, including between Lebanon and Israel, that preserved Israel as cosseted in a super-national of regional consensus on its autonomy as a state. Israeli independence was recognized without qualification in “The New Middle East” he invited the General Assembly to visualize. That global perspective may have been unexpected, from a nation that has been focussed on barrier walls, but was not asking them to visualize peace. The map is an open affront to the General Assembly, eliminating non-state actors in a community of nations, and mapping the nemeses of the Israeli state against a trans-border entity that the Assembly’s failure to comprehend could not be expected–it didn’t seem likely given that it was cast “a swamp of antisemitic bile” from which Israel was increasingly quite desperately left isolated.

Netanyahu had deployed a different infographic–a ticking bomb!–to demand in 2012 the General Assembly recognize “a clear red line” about Iran’s nuclear program, as if addressing kindergartners by declaratives such as “This is a fuse” and “This is a bomb,” to demand nations adopt “a clear red line on uranium enrichment” for the future of the world, not Israel’s future–for nuclear weapons “in the hands of the most dangerous regime” would become corrupted “by the lust of violence”–we must prevent Iran’s access to a final stage of access to high enriched uranium, that would allow the Iranians to complete a true bomb to which it was per open data 70% of the way to possessing–

–and, he grimly concluded, allow Iran, a rogue nation, to arrive at full possession a nuclear bomb–

Netanyahu Addresses U.N. General Assembly on September 26, 2012

–that Netanyahu used a sharpie to prevent, beseeching the United Nations a decade ago force Iran to “back down” not only from introducing nuclear weapons in the Middle East, but upset the balance of power in which Netanyahu claimed he sought to “forge a durable peace with the Palestinians” that had long been elusive, implicitly blaming Iran as the chief bad actor to ongoing crucial process of peace negotiations to secure the recognition of a Jewish state of Israel. Netanyahu used public reports of the possession of enriched uranium, but turned to cartographic props in later years to describe Iran not only as enemies of Israel, but enemies of God, like the very Amalekites who it was the duty of the Jewish people to wipe and eliminate (Deut. 25:17-19), as they were of an order of evil and threshold of wickedness that demanded to be contained, Netanyahu has relentlessly, and per formatively turned to maps to erase occupied territories and Gaza, but imply, as his cartoon bomb, the fear Iran would enhance Hezbollah’s ability to strike targets in Israel.

The map seemed revised “Greater Israel” transcending its borders to a threatened nation, aspiring to normalcy, but threatened by the non-state actors tied to Iran, the “threat” or curse in a region where boundaries and borders made no sense. Netanyahu paradoxically condescendingly lectured the community of nations at the meeting of the 79th General Assembly to defend Israel’s conduct in war, without saying so, mapping the transnational ties that had become a threat from the perspective of an isolated country. This was the deepest reality Iran must understand, the states of the world must recognize it was impossible to tolerate any longer, and the reason for the border wars he was about to launch with increased intensity. The violence of the attacks, he seemed to be saying, or apparent violation of international law were the least of the world’s real concerns. The remainder of this post is concerned with mapping of the threats to Israeli sovereignty, the mapping of the borders of Lebanon that Israel invaded, and the question of mapping the future of the nation. When he returned to the United Nations on 22 September, 2023, no doubt enraging Palestinians in the audience, he displayed the future “New Middle East” with no Palestinian presence visible–

–in ways that this blog has linked to the invasion two weeks later of Israel in the Al Aqsa Raids, named after the old mosque in East Jerusalem whose presence was recently closed to Palestinians. That performative use of the map of a bucolic “green” future appropriated the green banner of Palestinians for a “New Middle East” that suggested a community of nations poised to recognize the legitimacy of Israel in 2023–Egypt; Sudan; Saudi Arabia; Bahrain–that appeared to welcome Israel as a “normal” nation in a map of clearly drawn borders.

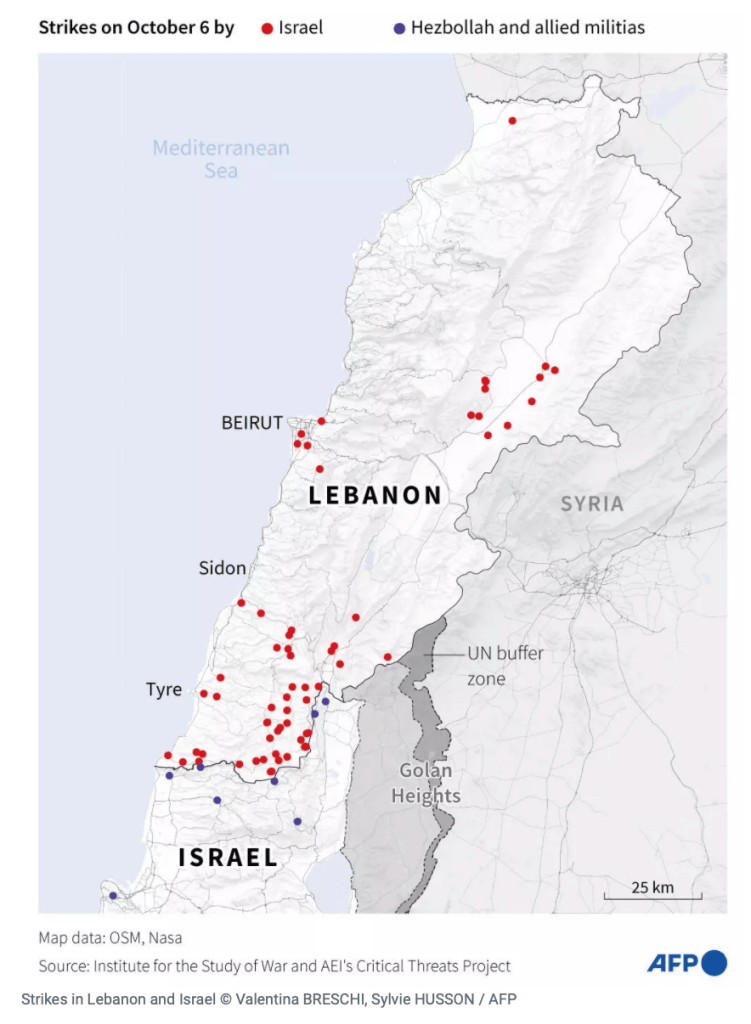

The strikes on Lebanon, he seemed to say, were the “domestic policy” of a “normal” nation. But the increased scale of the bombing raids that followed Nasrallah’s violent death under Israeli bombs led to a massive attempt to degrade the strength of Hezbollah on a region not imaginable before, providing a massive launching of air raids across southern Lebanon, focusing on the area below the Litany River in the southern part of the country, but extending up to the area below the Awali, the two proxies for the agreed lack of a border of Lebanon, as if to compel the United Nations and international community to accept the borders of Hezbollah’s presence in the nation and in the Middle East. The folks at “Understanding War” provided a far more sanitized image of the localized strikes that Israel had taken of cities or villages south Sidon, as well as just outside of Beirut–where they destroyed the compound of buildings where Nasrallah was meeting operatives of Hezbollah–including reconnaissance and observation points of the Israeli territory in the Golan Heights, based on local Lebanese reporting, that seemed destined to “degrade” the force of Hezbollah in Lebanon.

The demand for such a degrading of the border zone emerged as a logical response to waves of rocket attacks on Israel, mostly on IDF positions and an attempt on the Mossad headquarters outside Tel Aviv, the later fired in response to the bunker blasters that killed Nasrallah on September 27. The flurry of cross-border bombs can offer some clarity on a war that was still being called “focussed,” “targeted,” and “delimited” but appeared intended to secure a sense of lasting violation of borders and sovereign integrity, and to reassert its control of the area south of Sidon.

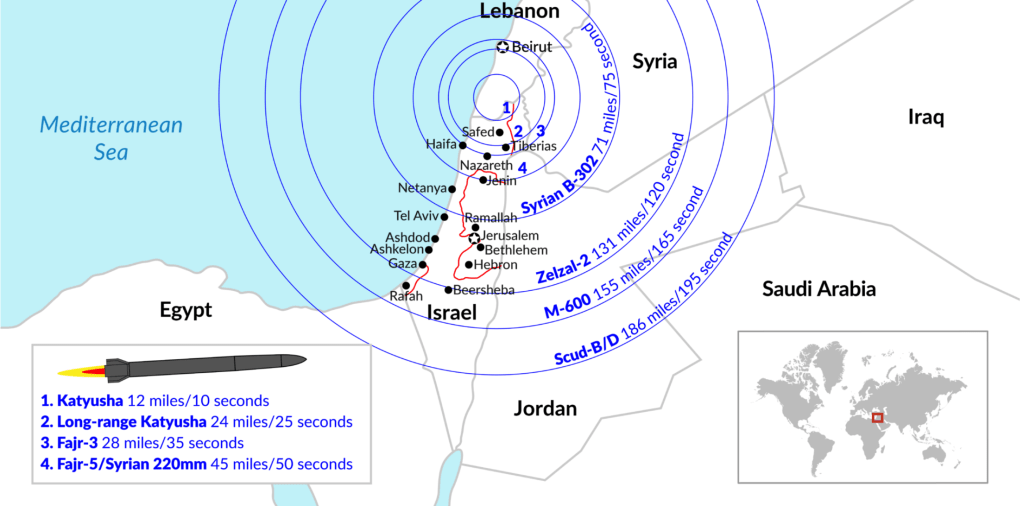

Capacities of Hezbollah Missiles Striking Deep within Israel/BBC, via CSIS, AFP/October 1, 2024

To a certain extent, the targeting of the southern third of Lebanon made little tactical sense, with missiles of considerable precision no reaching not only a forty kilometer rang of Katyushas, but the seventy-five km range of Fajr-5 missiles, the Iranian made long-range multiple launch rockets named after the morning prayer, first developed in the 1990s. modernized with GPS guidance in 2017, or the two hundred and ten km Zelzal-2 long range unguided rocket–Persian for “Earthquake”–which promises an enhanced level of local destruction upon impact, but also offers far less precision, but the Israeli precision strikes seemed surgically elegant, but seem to respond to the increased accuracy of short-range missiles, and the hope of removing the threat of cross-border strikes of increased velocity and defined by “more accurate, more precise, multidirectional fire” for the past six years of increasing chances and worries of cross-border war, in many ways more salient than the Gaza Strip had ever been in the previous decade, per the IDF’s former chief of operations.

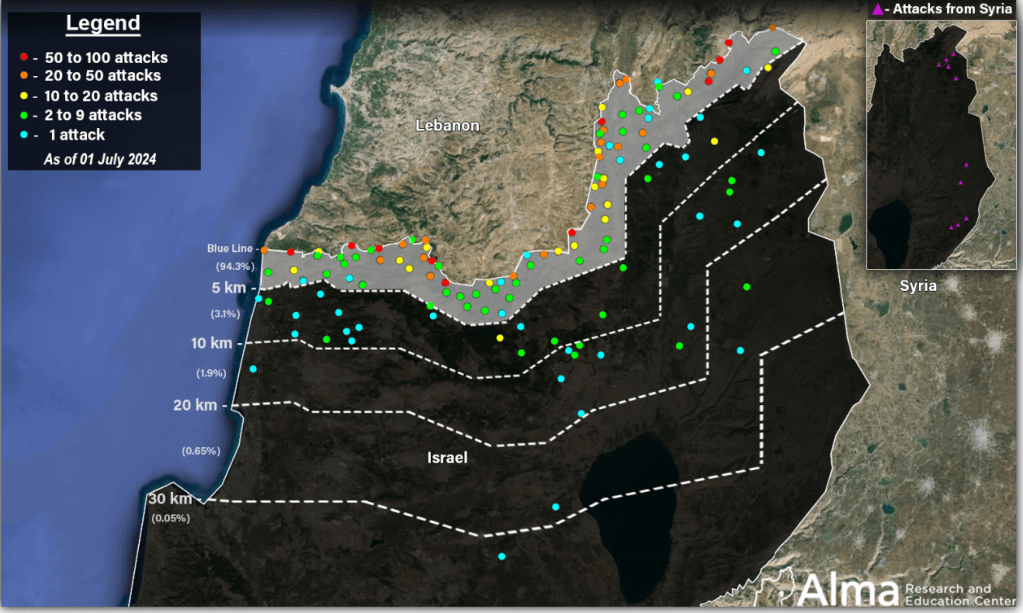

Vulnerability of Israeli cities to Syrian-Made and Iran-Made Missiles/GIS Reports Online, 2018

From October 2023 to July, 2024, there were over 2,295 rocket attacks on Northern Israel, displacing many, but over a far more limited range than the study of Syrian rocket ranges revealed, mostly confined with in 20 km of the armistice line, and few beyond 30 km of the border, designed the abilities of Syrian and Russian long-range missiles, whose use was understandably restrained–the greatest majority within but 2.5 km of the border, and 94.3% within half a kilometer of the border.

Attacks on Israeli Territory, October 8, 2023-July 1, 2024/ALMA

Netanyahu seems to have won Americans go-ahead for “for dismantling [Hezbollah’s] attack infrastructure along the border,” assurances bolstered when US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin “reaffirmed US support for Israel’s right to defend itself against Iran, Lebanese Hezbollah, Hamas, the Houthis, and other Iran-backed terrorist organizations.” Although Hezbollah had no intent to withdraw from the border, viewing its fostering of a “resistance society” as a prelude for the collective annihilation of the Israeli state, if not the annihilation of Jews that suggested defense was only possible by all-out war. While the lame duck American President bravely held out hope for a ceasefire, the war on the border had raged for weeks, and wouldn’t stop soon. In launching fireballs and incendiaries with trebuchets and from missiles, a border war of new intensity and scale had emerged for which Gaza may have been a rehearsal, and the purported choices of two maps–a “blessing” of alliances and a “curse” of Iranian proxies’ victory–is itself a smokescreen.

Or was the map not only a smokescreen, but demands to be taken seriously as a counter-map of the maps of bombing raids that he at this point knew were imminent, and underway? The deployment of the bunker-busters was not taken light heartedly and without much internal debate with members of his cabinet; the blast that seemed a veritable hand of God and strike of death for the elite commanders of Hezbollah and their General Secretary was sought to be explained, before it happened, by the lamentation of the situation in which Israel found itself. The map provided a “message for Teheran” Netanyahu had traveled to New York to bring–“if you strike us, we will strike you “–invoked the absence of borders, opening a window to escalation or a imminent missile strikes from Iran threaten. No magic marker was required, or any clear rhetorical hectoring of his audience–he seemed now heavy lidded and quite tired as he spoke to the General Assembly, with full foreknowledge of his order to send the bombing strike that would assassinate Nassrallah in his hiding place. The visual aids keyed to a language of biblical derivation, oddly misplaced on the modern geopolitical situation of Israel, was a language of self-preservation and of flattery–Indian media seemed a bit overjoyed it had been identified as “The Blessing,” irrespective of the dark side of these visual aids–the “dumb” map of the political dilemmas of the Middle East evoked the very biblical terms in which he had cast his retributive strikes on Gaza, and would now strike Beirut.

September 22, 2034

Continue reading

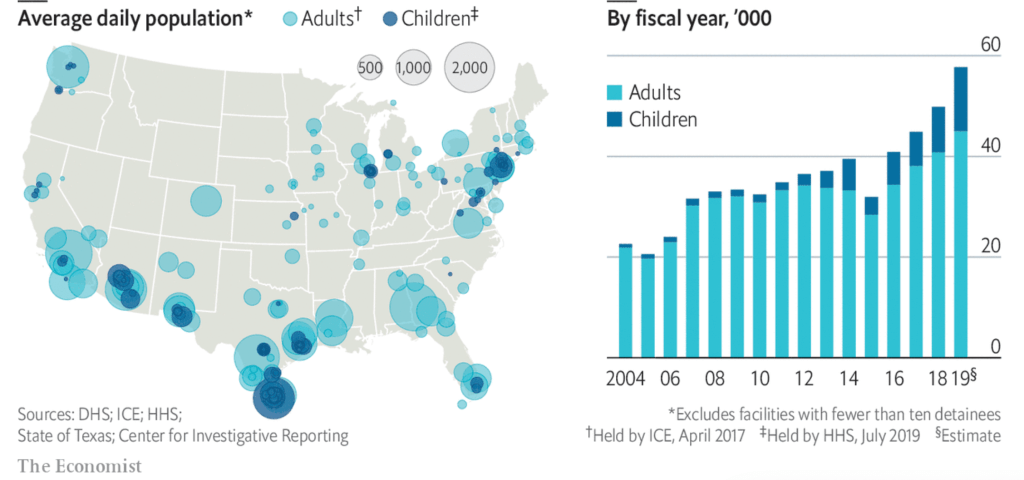

Kendrick, “And We Open Our Arms to Them”

Kendrick, “And We Open Our Arms to Them”  ICE Arrests of undocumented immigrants, 2014

ICE Arrests of undocumented immigrants, 2014