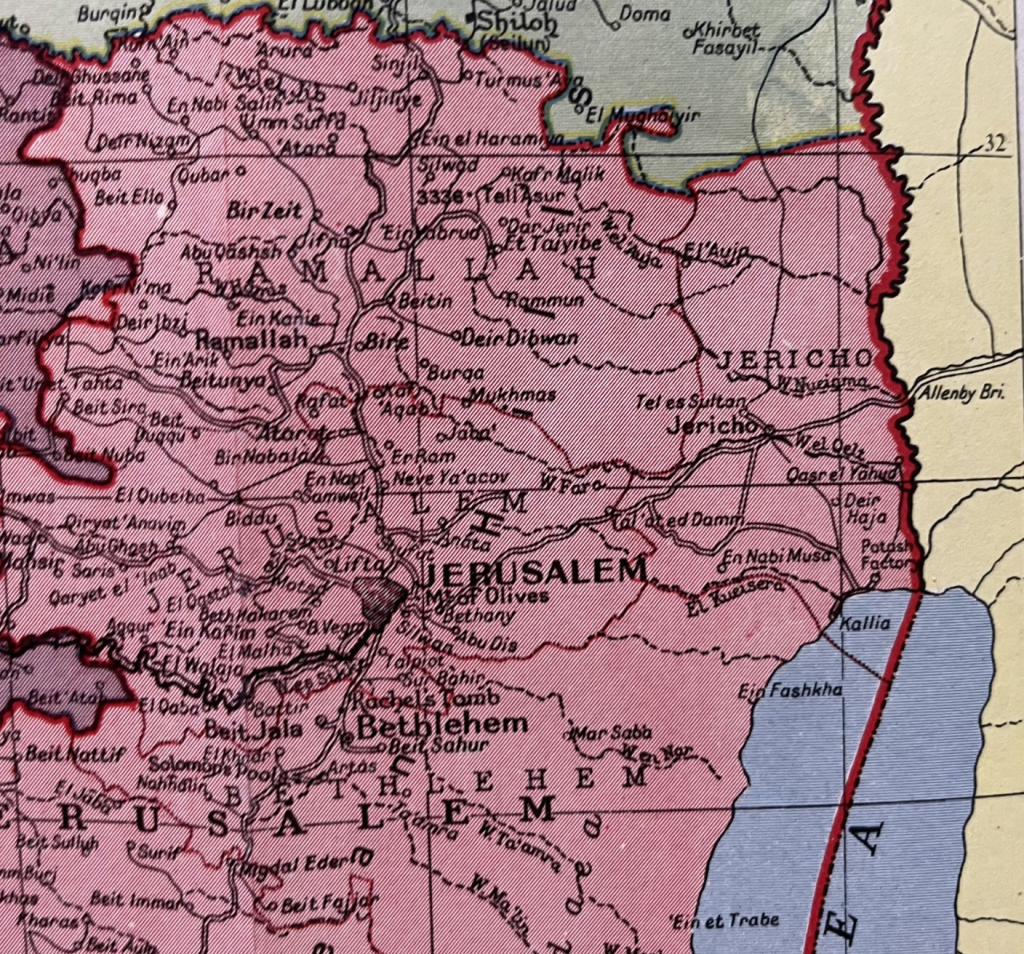

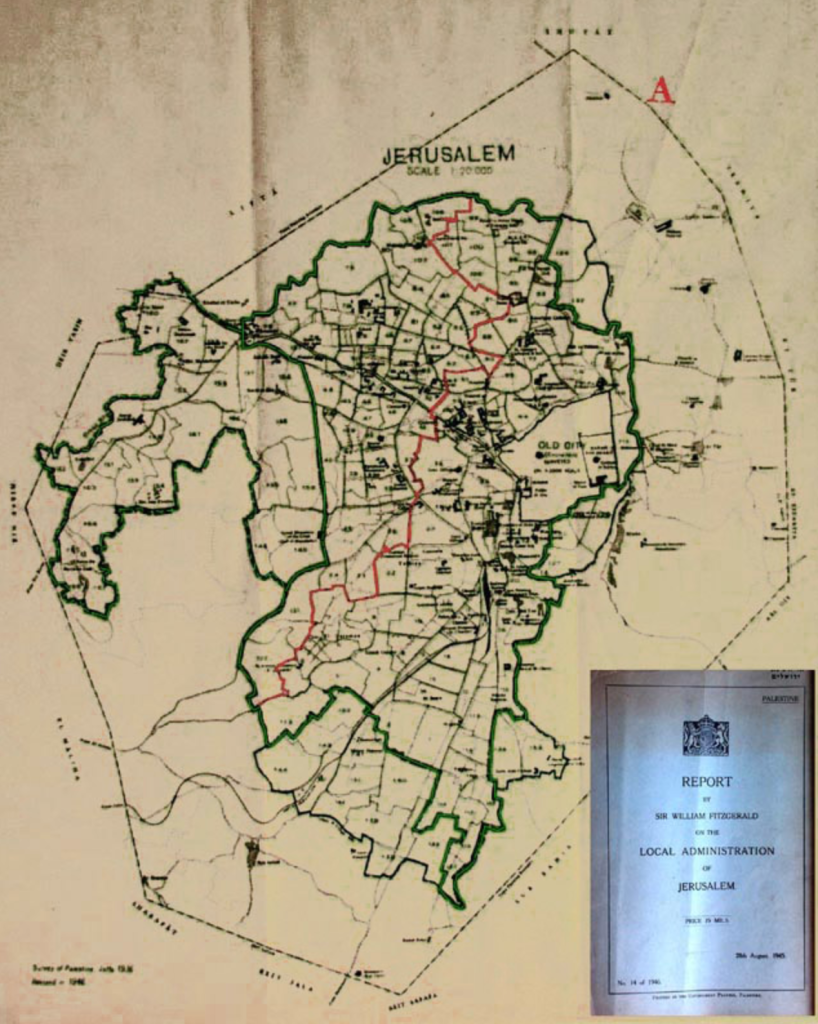

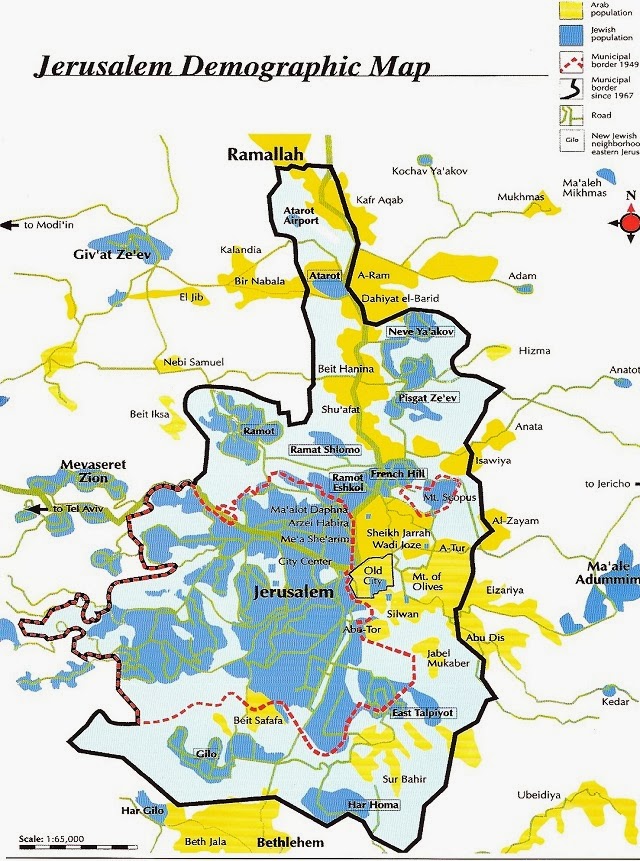

When I attended High Holiday services in an Orthodox synagogue in Oxford just before the October 7 attacks, it was probably for the first time in some years. I was terrified of how to fit in. But the spatial imaginary that unfolded in the services days before the invasion of Israel’s “border barrier” on October 7, 2024 suggested how difficult the geography of the Middle East would be. Although it was familiar, I stopped at an old prayer in the Makhzor, or holiday liturgy, praying for the safety of the Israeli Defense Forces as they guard Israel’s boundaries over the coming New Year, 5785. The creation of these boundaries was noted not in a moment, but have, changed over time. But the notion of fixed boundaries of Israel that Benjamin Netanyahu has long proposed in stated policies that have openly vowed rejecting any attempt to create Palestinian state between the River Jordan to the Mediterranean in a “Great Israel” had demanded Israeli control from the river to the sea–even if the area includes, according to Israeli demographer Arnon Soffer, of 7.53 million Palestinians and Arab Israelis and 7.45 million Jews of fifteen million residents. The shifting politics of the population, and indeed its distribution beyond the previously settled boundaries of the Mandate of Palestine, and indeed the 1967 armistice lines after which Gaza was first fully occupied, suggests the problems of settling and settlement that were so crucial to the current protection of the boundaries of Israel as a state–and the anxiety of their defense–in ways that made the prayers to the guarding of these boundaries unsettling if the concept was of course familiar.

The prayer was familiar, but stood out for me as I returned to religious service in a foreign country: the collective imprecation to preserve the IDF currently defending the borders of the Holy Land suddenly seemed an aggressive act. While the Jews living between the Jordan and Mediterranean are in a far more continuous space, in comparison to which the geographic space of Palestinians is of course a far more fragmented mosaic who are without comparable rights as citizens, the borders have been reified by boundary walls in an era when borders are not only far more heavily fortified than ever in the past. For the border barriers around Israel hold mental space before the cry to free the region “from the River [Jordan] to the [Mediterranean] Sea“–a slogan firmly rooted in aspirations for decolonization struggles of the 1960s, if to some ears maddeningly intentionally geographically vague, in ways that were seen as implying annihilating the Land of Israel Jewish state. But the deep insecurity that the cry seems intended to trigger, erasing the consolidation of land within Israel’s new physical barriers on its frontiers, evoke the precocity of the state in ways that the sudden. October 7 invasion from the Gaza Strip seem only to have been planned to promote.

But rather than confront the question of the continued denial of Palestinians citizenship or rights in a nation bordered by fixed boundary walls, the ongoing vigorous mapping and remapping of Israel as if it were a right of self-determination seems to be what the call to action seeks to place front and center. A counter-mapping if there ever was one, the erasure of Palestinian presence in the region that dates from the War of Independence has begun a cascading struggle to be contested and renarrativized in maps, making the mapping of Israel’s boundaries not only a historic removal–a fait accompli that one has to ask Palestinians to ‘get over’–but a living legacy that has been sought to be bolstered to a state of quasi-permanence any the bonding of ‘Israel’ by concert barriers and razor-wire topped fences manned by soldiers, more than a Zionist dream. The mapping of Gaza was not, perhaps, I was thinking as I read the letters, so far distant from the heady dreams that my father felt, in 1951, flying from Buffalo, NY to Amsterdam, before taking a train to Marseille and a boat to Haifa, amidst immigrants and refugees eager to arrive in a newly founded state to defend its boundaries, living for seven months at the renamed kibbutz of Gesher HaZiv, restoring the Hebrew names of the land, just ten minutes from the Mediterranean and just south of Lebanon.

s The kibbutz is fairly typical in that it was settled immediately after what was then patriotically called the War of independence, on the edge of the Lebanese border and the edge of the Evacuated Zone of southern Lebanon, recently the subject of Hezbollah attacks. If Gesher was a kibbutz by 1951, seventeen years before the kibbutz was founded beside an ancient bridge after the construction of a hydroelectric power plant, the old kahn Jisr al Majami was home to 121, including 112 Muslims and 4 Jews, by 1931 attracted over 300 Jewish settlers to cultivate oranges and bananas, and the kibbutz built atop the ruins of the old fourteenth-century kahn of which no traces would remain. When he travelled to Jerusalem, in late November, leaving the settlements founded in the 1920s, it seemed eye-opening as the landscape was so heavily inscribed with its own history of a recent war that he had been studying in class: a torturous trip through the hills of the Jerusalem corridor on the way to the northern Negev revealed extensive cemeteries of groups of soldiers who had ‘died defending the area–groups buried together according to the battles they fell in–rows of small white markers sectioned off’ the material record of the considerable ‘price paid for the hilly rocky corridor to our capital–for lifting the siege of Jerusalem.’ The journey that led him to view the ‘old Biblical city’ led him close to Gaza–near ‘where Samson and Delilah chased around,’ and in his visit to the coastal plain of the Mediterranean near the current Gaza Strip, a border of Canaan, as the Gaza Strip near Askelon–aware of the new policy of renaming, as Meron Benevisti, former deputy mayor of Jerusalem and historian helpfully put it, much ‘like all immigrant societies, we attempted to erase all alien names,’ and the ‘Hebrew map of Israel constitutes one stratum in my consciousness, underlaid by the stratum of the previous Arab map’ that it conceals. As an American, was the similarity to the renaming of upstate New York’s older native names not a possible parallel? The warrior Samson, delivering Israel from the philistines, provided a model as much as David fighting Goliath, provided a model, even if that weakness for the philistine women was potentially able to make the walls come tumbling down.

–became in the 1950s an industrial area indcluding a mammoth cement factory, electrical plant ‘to be run by Israelis’ and nursery of a million seedlings ‘for reforestation of the surrounding areas,’ more than a muscular site of combat that needed to be defended. Despite the expansion of severe restrictions on Palestinian ownership of land after the occupation of Gaza Strip in 1967, in hopes to prevent Palestinians from expanding abilities of permanent construction or economic development, the industrial zones that were planned for the Neshler Plant to provide housing for the expected waves of immigrants that were hoped to arrive in Israel from the early 1950s–realizing the 1902 demand Benjamin Ze’ev Herzl had that ‘the construction of a state for the Jewish people must also take into account the founding of a Hebrew cement plant.’ The foundation of the plant in Ramla, as David ben Gurion proposed building a second in Beer Sheva, completed in July, 1953 was what my father witnessed, that produced bags of needed cement from August, 1953.

The trip that was sponsored by the Jewish National Fund, a major player in national development from projects of land reclamation and marshlands to afforestation to prepare land for settlement in large public works projects was based on a long-term Zionist effort to raise funds from Jews around the world to purchase lands for future settlement, growing form 25,000 acres in 1921 to double by 1927, founding some fifty communities, and by 1937 planting over 1.7 million trees in the Holy Land, that gave a new sense to the Jewish festival of Tu BiShvat, the New Year of the Trees, celebrated as a festival and a celebration of tree-plantings. Indeed, the stamps that my father sent home were uniformly a glorification of agricultural work, in keeping with the fiftieth anniversary of the Jewish National Fund, the main operation that had brought him to Israel to help ‘redeem’ the land–a project still celebrated in Hebrew, English and Arabic, reflecting the vision of a united state. That project of redemption has long faded into the past of an ideal of farmers nourishing the land.

By 1939, ten more cities were built by the JNF, including the Negev and Galilee, purchasing land for new communities that began in the war that housed European emigrant, focussing on the settling of the Negev and south–areas that were banned from settlement in the Mandate–as the JNF readied with new determination after World War II to launch a large-scale settlement campaign from 1946, based on the Zionist Executive’s fear that clear British planned to confine settlement to a small region outside a planned British protectorate in the south of the country, as they had greatly expanded land holdings beyond expectations of the first settlers, the map inviting but its borders were afraid to be clearly defined, as operation of settling the lands grew for collective farms.

If settled the land had no set bounds, imagined to be steadily reclaimed quite expansively. And by 1948, some 650,000 Jews had resettled 305 towns in the future state, the great majority (230) on JNF lands; by 1951, the fiftieth anniversary of the JNF, Israel’s population had doubled in but three years since its founding, setting the stage for a push of intensive afforestation began in the Galilee, where my father arrived, as the Martyr’s Forest planted for those killed in the Holocaust victims. If Jerusalem was not clearly on the map, the place of the settlements clearly was–

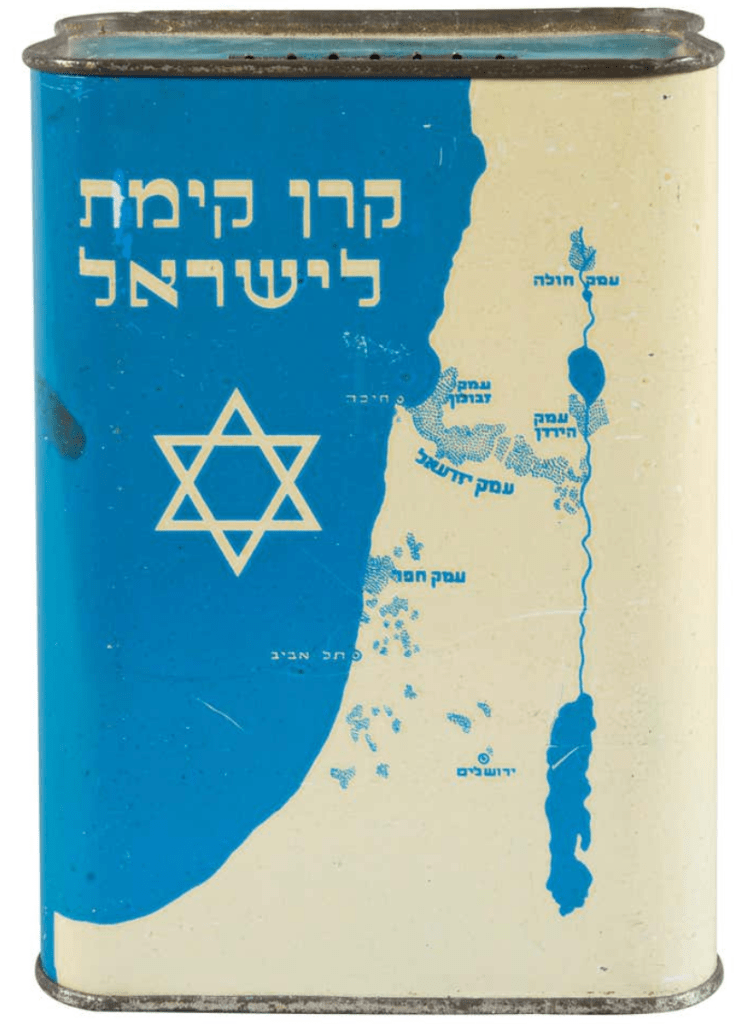

Map of Settlement circa 1925 in Jewish National Fund Tin Charity Box, Made in Ertez Israel, Keren Kayemet Yisrael (Design of 1930s and 1940s)

–suggesting an image of the conquest of space at a remove, but whose target near the Dead Sea was clearly identified as the holy biblical city of Jerusalem.

While the image of such an improbably conquest was removed from the land, the map that focussed on the Hula Valley, Sea of Galilee, and Jordan Valley offered a spatial imaginary that preceded the state. The Jewish National Fund’s ‘blue boxes’ symbolically mapped a covenant with the project of settlement diffused globally in the interwar period; the JNF indeed had by unification accumulated highly valued land across Palestine that were mapped with some precision in the diaspora, by 2015 holding some 13% of the lands open to settlement–if the plan to sever its covenant with Netanyahu’s state that year, as was planned as far back as 1961, was feared to plunge Israeli real estate markets into chaos.

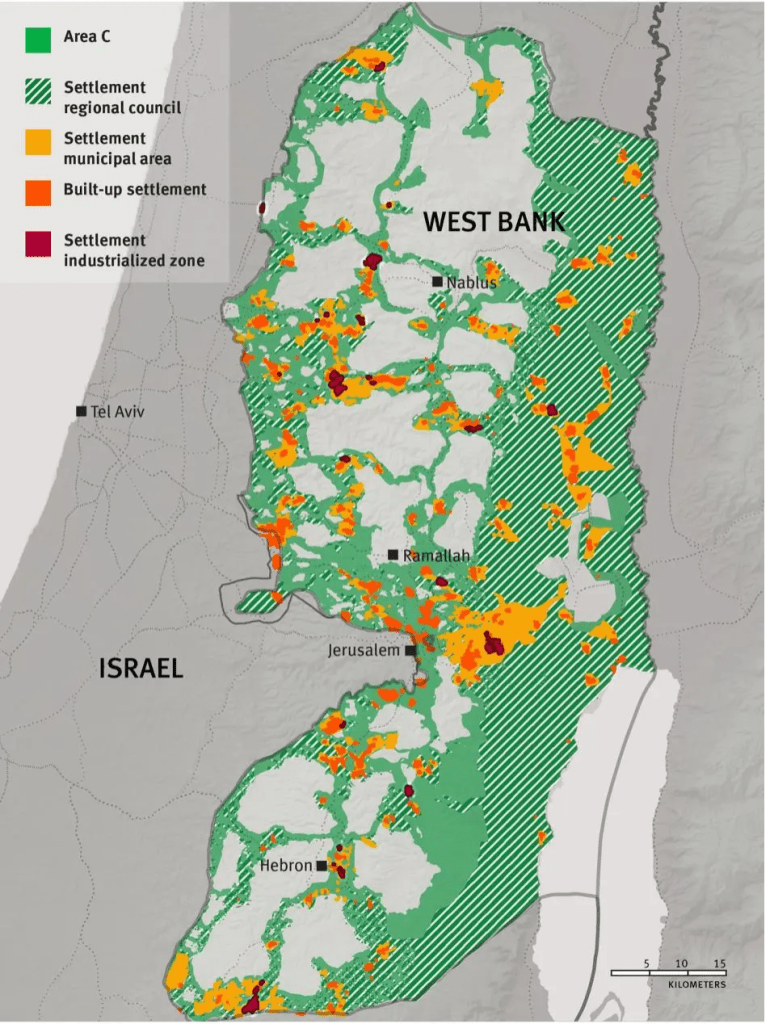

Into this breach, with huge consequences for global geopolitics and indeed for the Gaza War, as the JNF helped to support the continued expansion of settler groups in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, the great-grandchildren of the owners of these charity boxes in the United States helped to donate millions to construct new homes for settlers that would displace the Palestinians, already long restricted from owning property from 1967 in the Gaza Strip. The current expansion of ‘settler colonialism’ in much of the margins of the Israeli state, creating a massive 26% spike in settler housing from 2015, foregrounding outright land grabs rather than purchased plots, often illegal, to reclaim Palestinian lands as ‘outposts’ of future territorial growth. By 2015, a full 15% of Israel’s Jewish population resided in settlements outside 1967 armistice lines of 1967. And the rapid defense of these settlement colonies in response to the attacks of October 7, 2023, revealed how intense the conflicts of religious settlement was on a global stage, as Netanyahu grew increasingly tied to American Republicans, and the delivery of increased weapons to Israel to defend its borders, and a growing right-wing support for Israel settlements in a new geopolitical map–and was based on the demolition of old houses with support from America, partly from fundamentalists and hard-line Zionists, that forged new and unprecedentedly convoluted if deeply symbolic transatlantic ties.

Human Rights Watch/map by Btselem, 2008, 2014

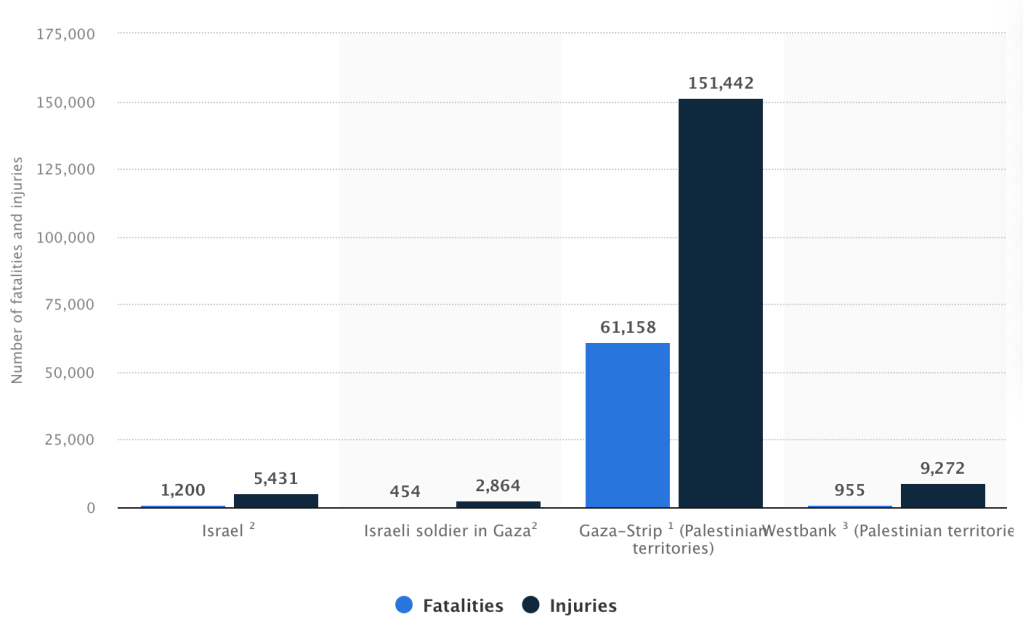

The regions of settlement were more a hope in 1925, of course, when early Zionist aspirations for claiming land, a claiming of land that has increasingly been at the cost of so many lives, both Israeli and Jewish, as well as Arab and Palestinian, that left not only 70,000 dead or trapped under rubble after two years, and almost 74,000 by 2026, according to the Gaza Ministry of Public Health, with some 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals killed in the original attacks, and an incomprehensible level of bodily harm and loss only confined to the Gaza Strip–

–makes the defense of these boundaries both difficult to understand, and less dependent on any objective mapping, so much as the deeply psychic maps or symbolic mapping of settlement staked in the spatial imaginary in KKH collection boxes long ago, that spread a spatial imaginary that transcended monetary value, or actual consequences and practicalities of settlement, and a density of settlement in the Lower Galilee–

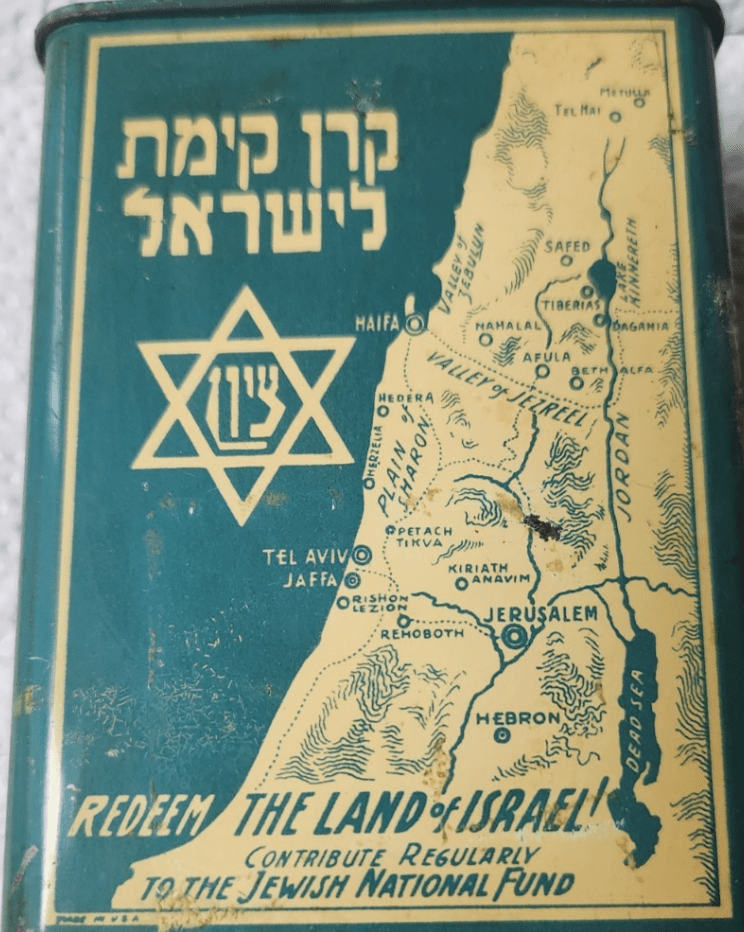

KKH Collection Box, undated

–offering clear and crisp toponymy in Hebrew script of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Ber Sheva as objectives far more durable than the tin boxes that they were manufactured to hold, but that even eerily seem to prefigure the very tools of data visualization increasingly central tools we use to visualize the ongoing if not seemingly unprecedented or unimagined intensity of this border war–

KKH Collection Box, c. 1925 (detail)

–casting the process of land redemption as a literal redemption of the land before Israel’s founding, of which Jerusalem, just off the West Bank of the Dead Sea, was clearly a target and eventual hope. The land was disused as not only mapped in detail, but by clear targets–indeed, striking Jerusalem as its capital, before the foundation of the state of Israel–

KKH Collection Box, c. 1940

After Jerusalem had indeed been secured the nation as the new capital of the state by 1951, when my father had arrived in the Galilee by the sponsorship of the Jewish National Fund, Gesher secured the hills near a large reservoir and hydroelectric station that promised the increased modernity of the process of settlement. The station and dam allowed the irrigation projects to flow to fertilize land reclaimed for farming, to feed an expected increase of population in a postwar fantasy of feeding and rebuilding the nation in the years immediately following World War II that had attracted a new generation of pilgrims and settlers to arrive from the United States. From imprecations to his parents that “I need no money–don’t you know that we can live without it?” in the midst of kibbutz life in mid-February, the collapse of the kibbutz project by mid-March led to requests for borrowing a small sum of money to extend his travels in Europe, promising to stay only in hostels and cheap restaurants, that ended up in his taking a boat back from Israel by the Spring.

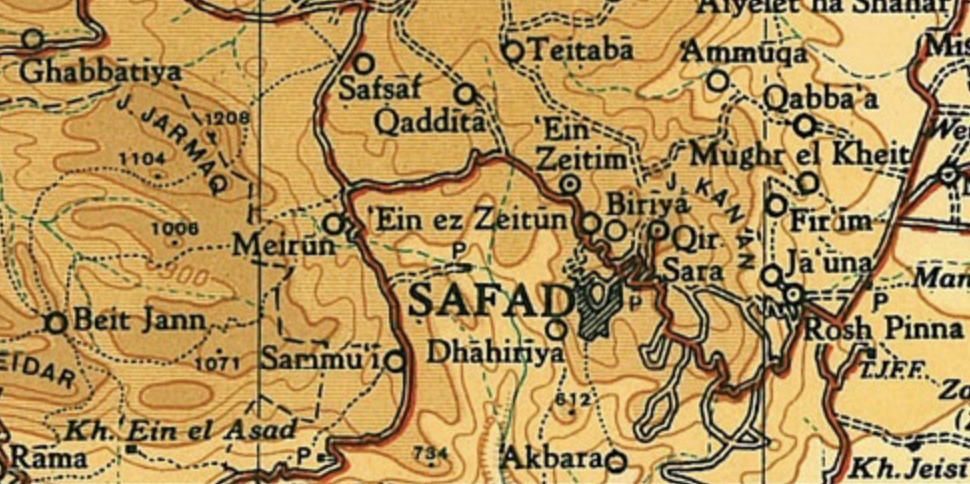

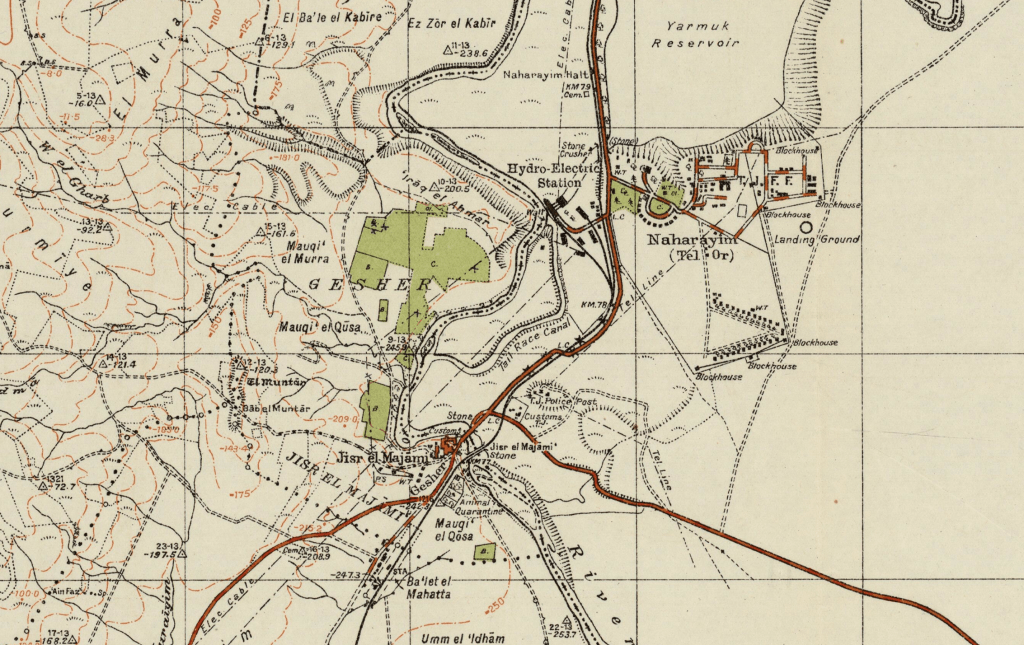

Gesher in the 1942 Survey of Palestine

For my father, arriving in Haifa in the fall of 1951, the War of Liberation seemed narrated as a distant past: the kibbutz founded by Armenian Jews, was a site for marvelous starry nights founded by a union and surrounded by mountains, a developed site of ‘bright, beautiful surroundings,’ and blue skies, near an ‘ancient Arab village’ that was by now abandoned, ‘dating back to post-Biblical times,’ and a crusaders’ fortress in the nearby countryside. Attending lectures on Zionist history for the first weeks he lived at the kibbutz, as well as on collective farming and Israeli history, he spent evenings watching films, seeing plays, or learning Israeli dancing. Hearing of a nearby orange grove, he was thrilled at a sense of safety; yet the dangerous proximity of a kibbutz near the border with Lebanon inhabited by Arabs was vertiginous. “From here Arab territory is easily seen from the second story of the [kibbutz] library,” providing an undercurrent of awareness of the past inhabitants of the land that may not have registered in hitch-hiking across a ‘beautiful country’ or traveling by tremp, or hitch-hiking, as the attention of kibbutzniks was focussed on the impending potential arrival of the two million Soviet jews then hoping to immigrate to Israel. He admired how formerly Arab towns ‘now settled by immigrants,’ and saw the ruins of the Independence War in the landscape as a cost that was needed for this way of life, to add a layer of security to settlement of these hills, newly terraced fo future agricultural projects essential to projected settlement, both to create a historically important ‘buffer’ between the states of Jordan that had claimed these lands, and secure the edges of the new Israeli state, as well as a site for feeding its population.

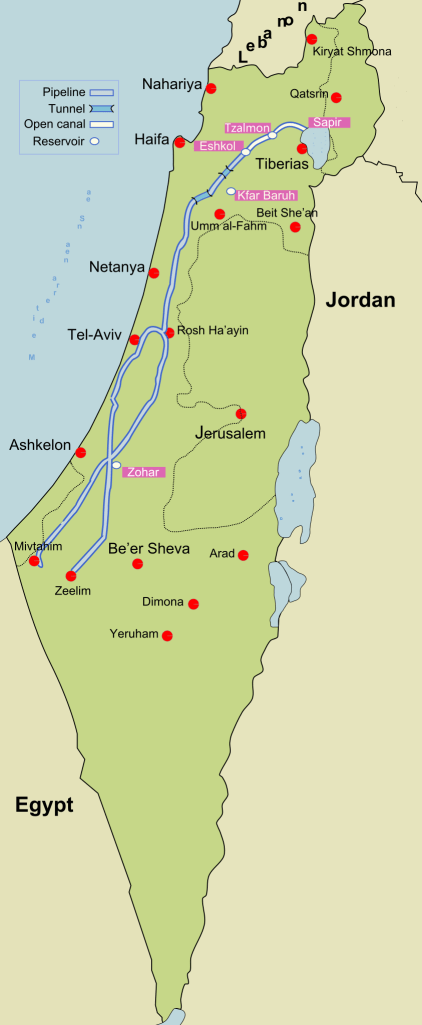

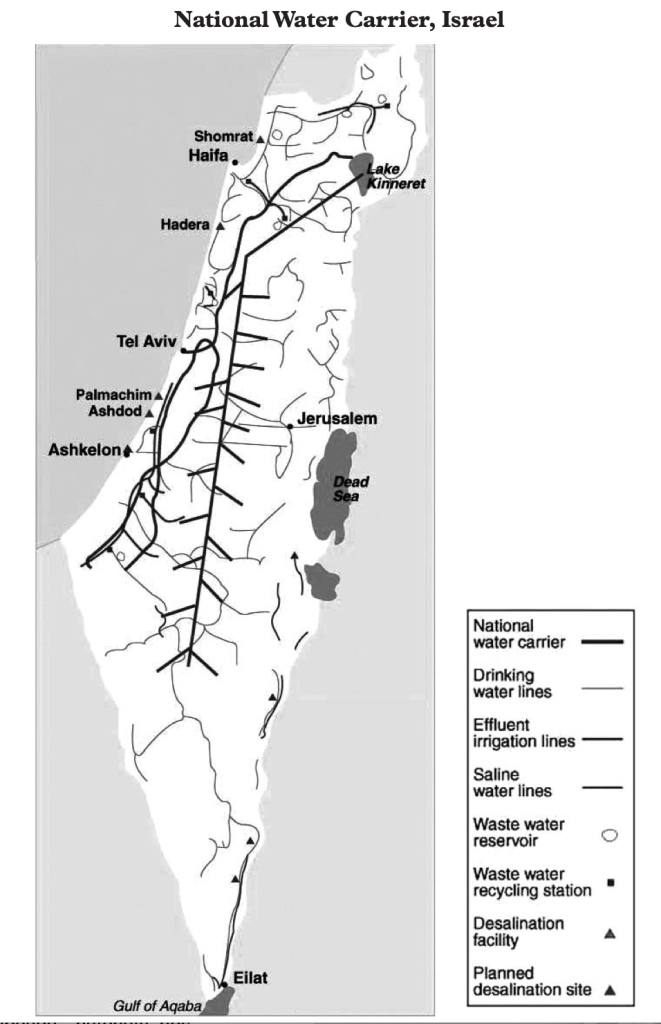

While the collective farms that were central to the foundation of Israel in the immediate postwar period were going through something of a crisis by 1951, facing problems in attracting new immigrants, the belief that more immigrants were about to arrive became a basis for believing in the growth of the state, even only four were established in 1950, and the possibility of more emerging was constrained by water, and the political divides that emerged between labor parties divided the logic of settlements, at the same time as kibbutzim were not attracting the waves of optimistic pilgrims that they had in the past. The situation was indeed rather grim on the ground, if the rhetoric of boosterism was stronger than ever, and the possibility of a major National Water Carrier was increasingly needed for future agrarian development in the nation, and increasingly dependent on a policy of the confiscation of lands from 1951 from Arabs, rather than the use of land purchases. Passing towns that had ‘passed from Arab to Jewish hands several times’ in the War of Independence, he presented his parents a picture of deep historical past that within three years since the war had receded to a distant time, transformed by the cultivation of fruit trees and olive trees. By Chanukah, my dad relished signing his name in Hebrew, having encouraged that his parents were taking courses in the language he’d mastered in summer camps in upstate New York, but was now using on the ground: and he offered them a map of the place of potential resettlement, where a few neighbors from Buffalo had moved. The National water Carrier that had expanded by 2015 was already drilled through some hills, from the large hydroelectric station off of after the first damming of the Jordan River in 1932-48 promised power for Mandatory Palestine, just south of the Galilee at the Huleh Lake and Swamps, central to the “All Israel Plan” of securing water from the Jordan for the entire country from the coastal plain to the Negev, in an artificial aquifer that has allowed the state to grow, and expanded by 2015 to a central artery of national infrastructure.

The rise of cooperative villages, which my father later visited, were hoped to be a way to make the kibbutzim more profitable, and permit private consumption that was not encouraged at the first projects; newspapers reported land reclamation projects best by ‘strife’ as dissension between the dominant two political parties created divides in kibbutzim based on alternative views of the future of the cooperative settlement–in ways that were only lessened by the construction of a National Water Carrier as now exists, offering a sense of limited coherence to the divergent political interests and hopes that exist entire country, but increasingly marginalize the West Bank and Gaza from the prosperity a Carrier promised the state. The National Water Carrier bolsters agrarian projects and provides water to the kibbutzim that have longed run around Gaza, as if echoing the boundaries of settlement, and providing little more than water waste recycling centers in Gaza and Ashkelon, and some very limited drinking water essential for humanitarian needs.

The geography was not about clear borders, but of an expanded new world of labor and work. When he asked the kibbutz members what had happened to the Arabs who had previously lived there he was, he later realized, met with stonewalling: they ‘went somewhere else’ or ‘left’ as if on their own desires. When he took an excursion from the orchards and vegetable gardens of the kibbutz with a few friends to another nearby kibbutz, Nir Ayliahu, still closer to the border, he seemed to pass destroyed towns in abundance, in which kibbutzniks lived among in sturdy settlements to reclaim the land by resettling them by irrigation of the land. The border was written ‘boarder’–not a spelling error so much as homonym implying the Arab town was impermanent, as the ruins of a depopulated Arab village led only to marvel at finding a landscape of “hundreds of such places all through the country as a result of the war” of 1947-49, the ruins of a distant past that mirrored the biblical landscape he learned about in finer grain, as if to map a new territory that, if from a scriptural period, was suddenly being realized and replacing depopulated villages that were being swept off the map of the State of Israel, defined by a National Water Carrier that segregated access to water of Palestinians form the Gulf of Aqaba to the Galilee.

There was even a vertiginous existential fear at a landscape where such continued evidence of scars of wars were all too real than they had ever been for Habonim summer camps, and from the kibbutz he heard–in terms of an angriness I recognized, but was embarrassed to read, ‘the noises from a dirty little village across the way came from a dirty little village across the way came from people who yesterday lent a hand in trying to destroy the very place where I sit today and kill off half of the people around me,’ a rant that was trying to comprehend the fragility relation to the present that almost might not have been.

The emergence of a distant past geography of the past in a wartorn landscape left little possibility of cohabitation with Arabs as neighbors or fellow citizens. He surveyed an Arab village populated by ten thousand on the other side of the border as an existential enemy, determined to deprive the reality of a kibbutz he lived and farmed vegetables, with citrus trees grapefruit and oranges in a biblical imaginary of a land of plenty, covered the ruins of a destroyed Arab village erased from memory. A few Arab villages as Tira, of several thousand inhabitants, still lay in Israel’s boundaries, allowed to survive. But the geography of Kibbutzim replaced that of Arab villages, and the seat of government that had been partially transferred, leaving some buildings the ministry of defense in Tel Aviv, to Jerusalem, deferring the question of how the governing of the land included Arab settlements, or suggesting, if unconsciously, that such ‘boarders’ lived within the ‘border’ of a growing state. Tara was just to the north of the kibbutz Ramat Hakovesh, or Pioneer Ridge, of seven hundred sturdy immigrants where he pondered they ‘borne quite a battle during the war of liberation.’ The kibbutz promised rapid transformation of the ‘barest’ of barren land, irrigating the slopes of hills to prevent the environmental degradation of the Galilee in the Palestine Mandate. The collective zionist goals espoused by Hashomer Hatzair had hailed from Northeast Poland, but thirteen years before a Nazi invasion decimated the towns seemingly providentially founded by a dedicated and ardent immigrants, who had camped on land they purchasing from an Arab family not long before the disastrous 1939 invasion depopulated the enclaves they had lived.

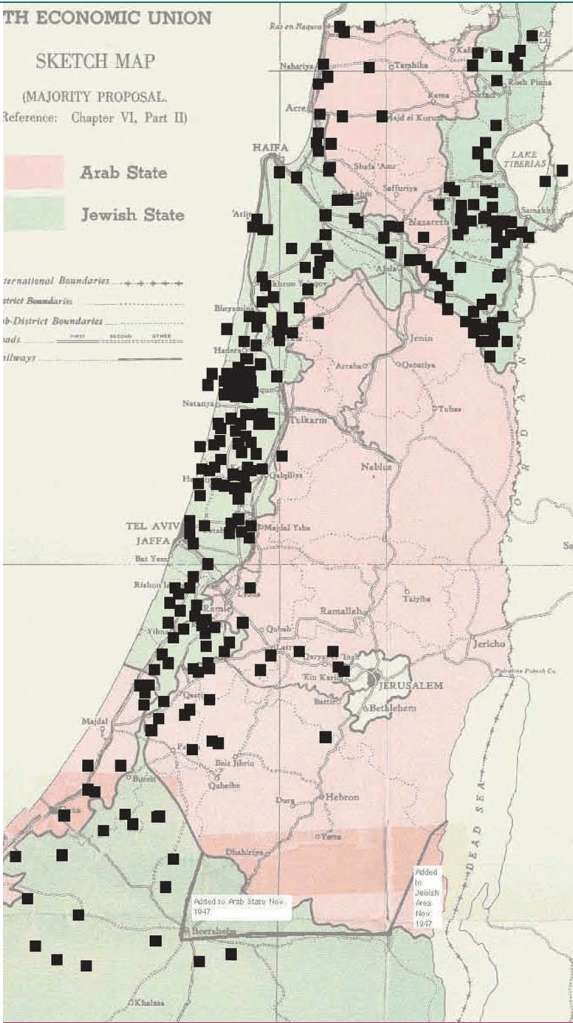

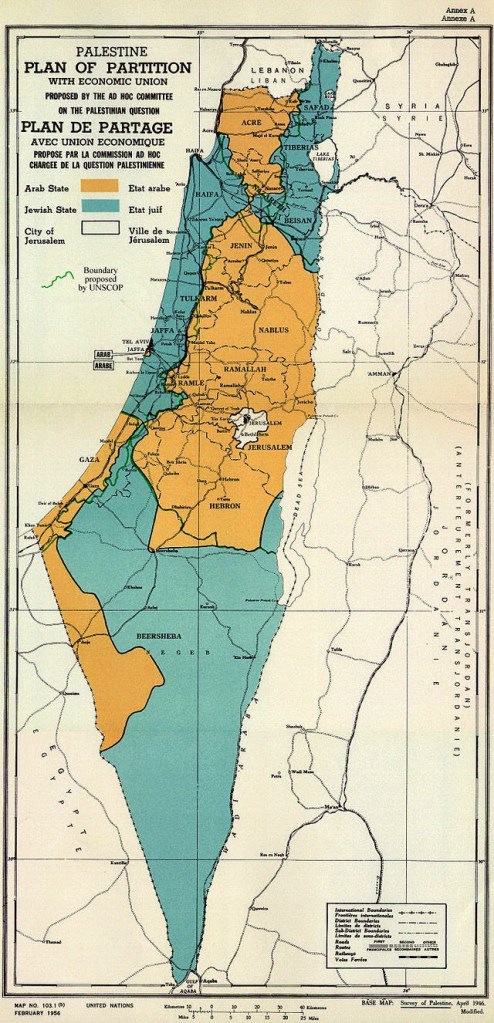

Indeed, in the years of the celebration of “Settlement Day’ by the cultural wing of the Israeli Defense Forces that included visits to kibbutzim located near army units, including the screening of films, lectures, presentations, and exhibits on Succoth 1948, by promoting ‘frontier sites’ as ‘the defensive walls of the state,’ the inaugurations of a ‘Settler’s Army’ was charged with the task of ‘the preparation of the land for massive immigration’ that was expected, President Chaim Weitzman proclaimed the need for continuing the war with the ploughshare and the book by agricultural settlement to determine the future of the Israeli state: by Israeli values: and by including new immigrants to the Land of Israel, the proclamation of marching to a ‘light of settlement and defense’ in April 1949 led to the creation of fifty two new settlements, of which thirteen were in the Upper Galilee my father lived for seven months, five in Lower Galilee, ten in the Jerusalem Hills, and twelve in the Negev. Three hundred and fifteen settlements were created in strategic ways across the nation from that The kibbutzim embodied the sense that manual labor would be a means of agricultural ‘conquer the nucleus of the growth of the Jewish population of Palestine from 25,000 in 1882 to 400,000 by 1940 to 600,000 by 1948, the foundation of the state, in ways that formed the basis for the United Nations 1947 Partition Plan, effectively securing the boundaries for the modern state. Settlements, in other words, both preceded and provided the precedent for the logic of the territorial state of Israel in the Sketch Map for the borders of an Arab and Israeli states in the 1947 partition plan, and indeed helped set the borders of the Israeli state.

With the eviction and relocation of existing tenant farmers in some twenty to twenty-five villages from 1901-1925, only some of whom were compensated, the departure of residents had opened the region to prospective residents of a “Jewish State” that might exist side-by-side an “Arab State.”

JewisEconomic Union Sketchmap based on Jewish Land Settlements of 1947 Proposed by UN 1947 Partition Plan. Black affixed squares of Jewish land purchases prior to 1948 against division of Arab and Israeli land

My father’s experiences at Gesher afforded an on-the-ground look at state formatino from the bottom up, based on the attraction of Americans and American money to energize the expansion of settled lands up to the outskirts of Jerusalem, and along the edges of the Gaza Strip and into the Negev. The newly terraced land my father helped settle in the kibbutz in Gesher offered confirmation of a far more efficient manner than earlier inhabitants had managed as if to illustrate the manifest destiny confirmed by the efficient application of years of labor to remake the land’s wealth in modern ways, impressed by encountering industrial engineers who had finished graduate work at the University of Chicago who were building the new country that would soon feature large airfields, and a ‘mammoth cement factory’ outside Jerusalem, in the rocky corridor of graves that marked ‘the price paid for the Siege of Jerusalem’ to capture ‘our capital.’ By Hanukah, studying Hebrew intensively for several months, he relished his father’s decision to begin studying Hebrew back home by taking to sign off letters in Hebrew script, accepting the new identity, dispensing tips on the festival in the reclaimed biblical language as a personal identity, as his increasingly personal relation to the land where the kibbutzim expanded and grew, disguising a colonial relation to the land, in many ways, as an unleashing of its wealth. The impression of the deep poverty of all Israelis for my dad led him to imagine a new relation to money, even if, as the kibbutzim ran short of funds, the need for more money seem to have sent him back to New York by late March, 1952.

The long-famous liberal Zionist pedigree of the founding and cultivation of this new relation to the land put into question by the October 7 invasion had set their primary mission to ‘conquer the land,’ without discussion of who resided there–and many of the kibbutzim around the borders of the Gaza Strip itself by Hashomer Hatzair members were placed on older Palestinian ‘Arab’ villages in 1949, perhaps even visited by my father, crating a sense that any place vacated by settlers would be filled by Arabs, and new American migrants might fill the land in proper ways for a new state, ‘conquer[ing] hill after hill without consideration for the law,’ as the current leader of the Kibbutz movement Nir Meir expalined recently, promoting the settlement of new communities to seed the land in Galilee, which is now half populated by Jews, rather than eighty-five to ninety percent inhabited by Arabs. Peace with Gaza would be, for kibbutznik near the Gaza border, a condition of trauma and victimhood.

The land of Israel was in large part forged not by governance of the land, but by the kibbutzim that celebrated a series of civilian outposts to take ownership of the land, and indeed establish the Land of Israel. At stake was nothing less than effective modernization, and the transformation of a dry landscape to a bucolic new homeland–the model for an effective state. If ‘the job Arabs did of terracing was pretty lousy,’ so lousy they were ‘unable to be worked efficiently by modern methods,’ the modern tools of engineering prosperity and supplies of food preserved the ‘remains of an old Biblical city’ with new and old settlements in the Judaean hills readied for reforestation that offered ‘beautiful views of the coastal plain’ and more than one ‘old Arab village’ in areas where kibbutzim had been established for many from around the world–South Africa, Romania, Iraquis, and Germans–actualizing a hope of resettlement unimaginable in earlier years. The new alliances that filled the transformed landscape of the Middle East suggested nothing less than the opening of a new world to which my father felt he was witness, invited by the Jewish state to observe the new wheels of global democracy in action in 1951, in between his occasional visits to the Americans from upstate New York who had returned to settle the Holy Land soon after the end of the War of Independence.

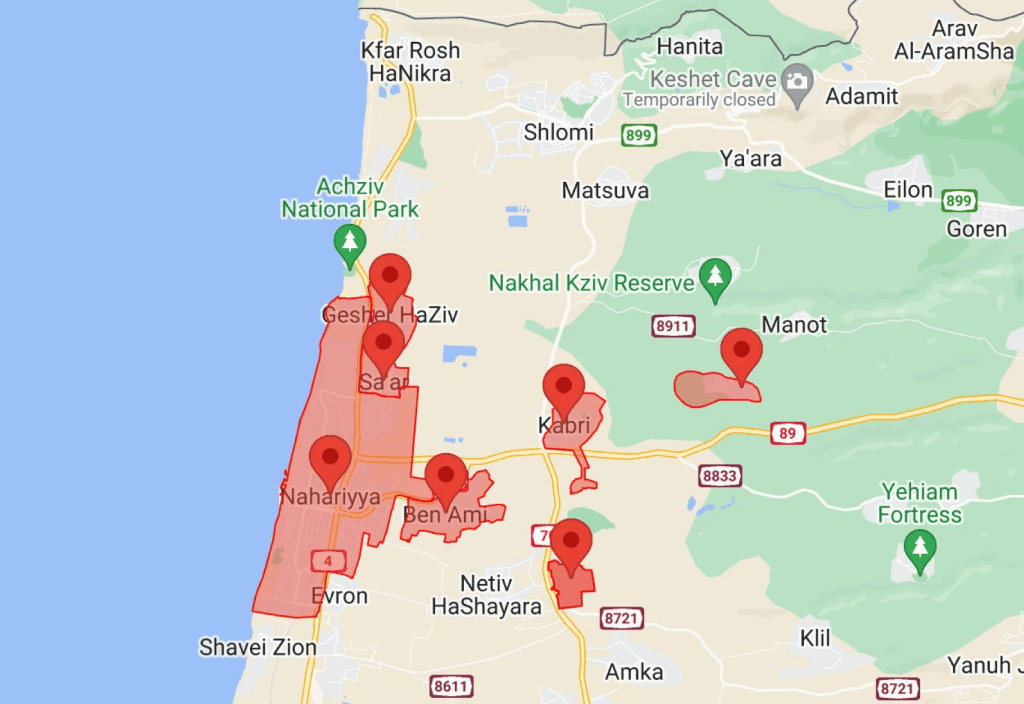

That the kibbutz in the western Galilee was just over three miles from the border with Lebanon would become the de facto border of the state in 2024, and the final stop before an evacuated zone, policed by Israeli Defense Forces,–but a hundred meters from the zone from which the Israeli army had evacuated all civilians after the Gaza War began. The kibbutz of 60,000 became an outpost of sorts in a game of territorial borders, its pastoral appearance concealing the increasingly vigilant prevention of cross-border attacks and skirmishes, or attacks by explosive-bearing aerial drones that is targeted by the 130,00-150,000 rockets and missiles targeting Israeli cities and kibbutzim. By August 2024, Gesher HaZiv lay directly on the Confrontation Line in the Upper Galilee, subject to red alerts as contested land.

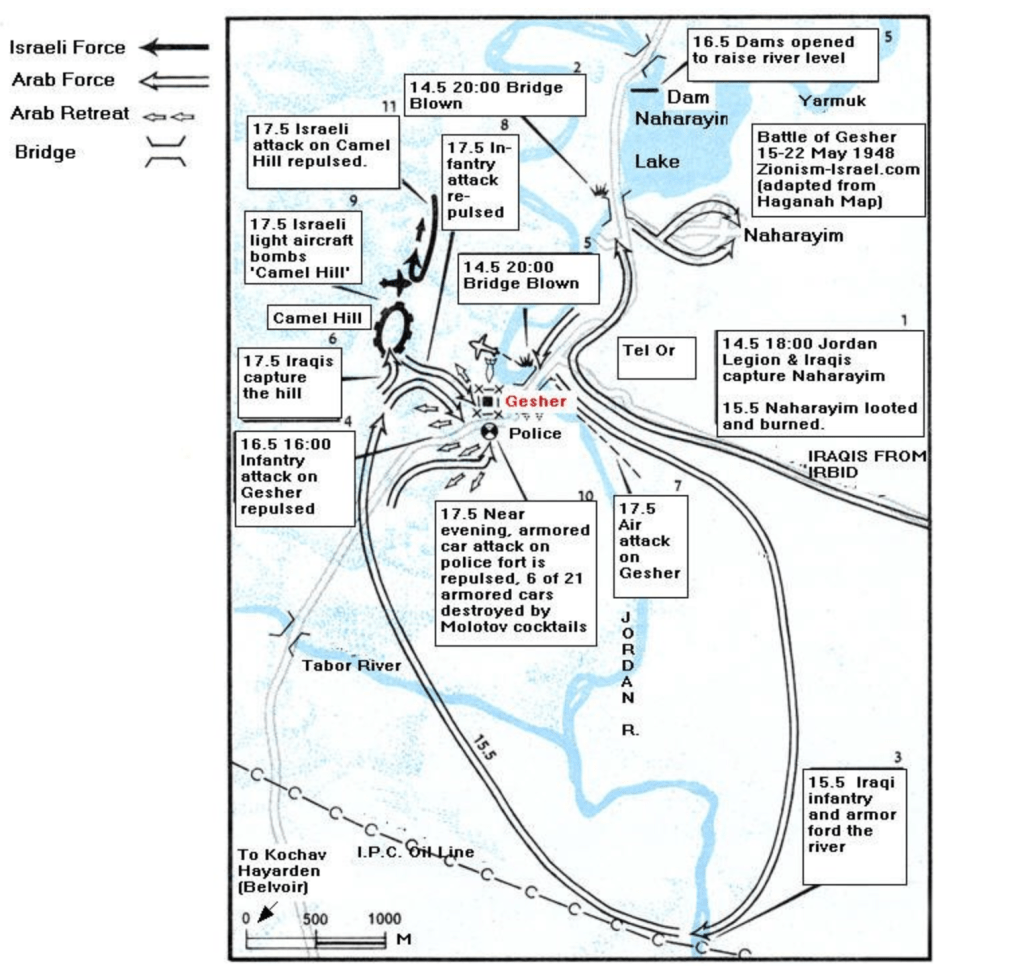

GISrael, Red Alert/@ILRedAlert, August 11, 2024

The kibbutz had been inherited as an outpost of the British Army in World War II, but was a site for war, before it became a site of Hebrew study of three hours a day, and privatized as a settlement in 1990. More recently, it has again become part of a war zone since Hezbollah had lent military help to the attacks on Gaza then day following October 7, a new reality of being a border town, and a hard edge of the state of Israel, increasingly demanding secure housing and military vigilance, if it was once seen as a tourist destination of Mediterranean architecture, serene gardens removed from urban life, promising ocean access to Achziv Beach’s tidepools, outdoors swimming, and camping in a large, bucolic national park. But the settlement of the United Kibbutz movement–‘Gesher’ means “bridge” in Hebrew, was an outpost founded in 1939 near the Naharaim bridge, reclaimed during Israel’s War of Independence as it was attacked by the Iraqi army and the Jordan Legion, is to the southeast of the Kibbutz, the original location a commemorative museum of the military battle. The erasure of contestation by agrarian work of fertilizing the long arid Galilee by water from the Naharayin Lake and the irrigation projects of the nearby Camel Hill provided a possibility of feeding a large populace of settlers, reclaiming the land by redeeming it for settlement, unlike the Bedouin itinerants who had lived there before.

Gesher HaZiv War

The original plan for the combined forces of Iraqis and the Jordan Legion to capture Afula changed as King Abdullah of Jordan told Iraqis the Legion would stay put in the West Bank in mid-May 1948, leading to the Iraqis to attack Gesher alone, eventually to be repulsed by Israeli troops from air and land, as troops from the Golan Heights forced the Iraqi troops to beat a hasty retreat to Samaria, and Israelis to secure the territory and a peaceful kibbutz moved to an English fort close to the sea, reclaiming a biblical historical landscape removed form the persecution of European nation states.

The Mediterranean was blue, and a site for fishing, swimming, and wonder. But there as little sense of war in its blue expanse as there might be of the Trojan War off of Greek islands like Lesbos or Chios, transformed by tourist traffic and beckoning as a calm blue. Yet when my father, retired, when to work for the summer and practice his Hebrew by talking to medical students in the Negev, working with psychiatrists from the West Bank in Bersheva, traveling with a Human Rights Group to Gaza to visit the Gaza Community Mental Health Center in March, 1994, between downtime with hikes in the Negev–‘flower’ hikes, wistfully–in towns filled with Russian, Ukrainian, and Romanian residents, as well as Bulgarians and North Africans, mirroring the global attraction to the kibbutzim of time past. The Labor ZIonist past of the kibbutznik past was gone, but perhaps able to be recuperated in old age, My father had been struck that Israel was able to be seen apart from an American perspective in the 1950s, proclaiming local understanding the Middle East as the Eastern Mediterranean, as if a maritime region without boundaries or nations.

Visiting Jericho, Bethlehem, and attending a ‘Trauma Conference’ in Jerusalem as he worked in Beersheva, the contested boundaries of the Middle East seemed something he might navigate as disputed territories with a sense of security; he sent me a card from Beersheba of a pair of elite rapid deployment IDF fighting force of paratroopers descending from an airplane as a comic pair, one with parachute fully open, staring at the other the other calmly relaxing without one. The red-beret paratrooper descended without parachute and with a red beret must have spoofed an iconic image of vigilance and military bravery long featured in enlistment posters from the 1960s,–

— as if an icon of vigilance concealed his own anxiety by local humor, as well as a reminder of my love of cartoons– perhaps the cartoons themselves were a frivolous medium that maybe were a sign of my own oblivious disregard of existential threats?

IDF Paratrooper Brigade Fighter Wings Badge of Cobra Snake

Maybe vigilance was not the point, but a new detachment from the political situation on the ground. When my father arrived in Israel in 1951, the glory days of the United Kibbutz Movement a massive way of collective settlement the contested Arab lands. If once seen as seamless with the Labor Zionist movement from eastern Europe and Germany, the recuperation of idealistic Zionism might include Arabs as well. But the hope to offer them ‘excess land’ by 1951 had all but vanished, with the loss of Socialist Zionism. The split of the United Kibbutz Movement the very year my father was working on a kibbutz between the socialist labor forces and led the agrarian settlement movement to fracture along the lines of a central schism of openly ideological nature. My father was stranded in the middle, in a sense, having tethered his dreams to the labor agrarian cause of collective work, that he would wrestle with the rest of his life, even as the defense of settlements became an increasingly prominent platform of the Netanyahu era.

If the Kibbutzniks were a form of early colonization, a ground forces of sorts that provided not only a claim to land, to resettle old Arab villages in a Nakba, but a demonization of their Arab-speaking neighbors as if invaders of a resettled sacred space, complete with monuments of actual biblical events that those making Aliyah could visit, but oblivious to the borders that were being created in ways that would be defended by armed outposts in the years after the so-called Palestine Partition Plan the United Nations adopted but four years before my father arrived in the new state of renegotiated and perhaps negotiable borders, before the Israeli army came to exist from militias that encouraged enlistment into “service to the nation” as a new ideal of nationhood, mobilizing the Israeli Defense Forces as a professional army to secure communications and continuity between Jewish territories to preserve a coherent nation.

Seventy five years later, the increasingly militarized borders of the nation-state made the prayers recited on the High Holidays particularly disturbing days as tensions grew in the days that preceded the October 7 invasion, an d the shock of an armed incursion of sovereign bounds of vicious civilian and military deaths. The fears of any assault of Israel’s territorial claims have been met by the increasingly intense fortification of its borders, a ramping up of its claims to “security” and “securitization” that has eroded the ethical values of the state, the defenses of these boundaries were both more militarized and less sustainable in the future, though which Habonim fell. The services that I attended in Oxford on the eve of the October 7 invasion included a prayer for the protection of Israel’s boundaries that placed dangers just beyond them. Having hoped to begin the New Year by hoping for the security with which they were guarded–as if they were granted by divine right but embodied by militarized defense–was unintentionally quite off-key, and made me grind my teeth during the High Holiday I had arrived to celebrate with some trepidation in a foreign country,–not seeking real friendship or continuity but hoping for familiarity as I set to orient myself to a university city I recently moved with my wife, trying to find some stability myself in what was in its own way a new land where I was more stranger than I’d expected, where I’d almost come to see myself as having parachuted but weeks before the October 7 invasion of Israel from the Gaza Strip. The prayer for the defenders of Israel’s secure boundaries seem to have sensed the immanent strike or need for protection, the threat having boiled over on the edges of the Gaza Strip before the invasion broke out so dramatically in international news to global shock. As belief in the regular degradation of Hamas forces in the Gaza Strip persisted, described now by the weird expression ‘mowing the lawn’ by indiscriminate bombing campaign, an attempt to disengage but preserve security, targeting and attacking the ‘captive population’ on the borders of Israel and refusing to negotiate. Bombing neighborhoods indiscriminately became rhetorically reduced to an operation of maintenance, whose consequences were never fully assessed.

While I was not concerned about Israeli borders, I was struck that the unexpected ritual invocation of the guarding of boundaries carried deep weight for the members of the congregation, reminding me that the prayer–an addition after the 1967 War– had long assumed deep significance. If the New Year’s holiday had some spiritual resonance and traditional power as a way of marking time, the sense of bonds among Jews grew with the coming invasion, making me negotiate my relation to the service I had just her. Indeed, the explosiveness of the invasion that left me and my fellow-expats reeling and hard to observe at a distance made me interrogate where that prayer had origins, and reflect how the literalization of a project of boundary-guarding had become so dangerous project of courting risks of raised the stakes, intentionally turning a blind eye. If the war was an invasion of Israel territory, the border zone between Gaza and Israel has, perhaps rightly, long been the subject of attention of Israel’s Prime Minister, who has repeatedly emphasized “stoppage points” and “closure” of the Gaza Strip and control of the border zone between Egypt and the Gaza Strip. The military securitization of these borders were hard to reconcile with the benedictions of the kindly rabbi. He led his congregation a final time in high valedictory form at the cusp of retirement, and stylishly negotiated the benediction to George V in our Mitkhor, to my ears, in an Anglican version asking for the safety of the royal family. In a sermon voicing dismay at the strain of lamentation strains of Judaism that he felt had infected or reconfigured Jewish identity at some loss of its original liberal optimism and pride, he wished us to engage the year ahead.

For a strain of lamentation, derived from the poetics of the laments of the Psalmists, but expanded to the elegiac account of suffering and commemoration that expand the liturgical elegies to accounts of forced conversion, expulsions, crusades, pogroms, and even assimilation short-changed pride of a “chosen” people, the rabbi felt, undermining a sense of pride. The ancient strain of lament in Jewish poetics and poetry certainly decisively expanded in twentieth century before inexpressibility of the Holocaust, and a need to express inexpressible pain in the face of fears of annihilation. But the logic of lament of would come to the surface with quite a vengeance after the unprecedented invasion of Israeli territory on October 7, only weeks after the rabbi’s sermon, as the unspeakable trauma of the crossing of the fortified border of Israeli territory opened existential fears that set in play a logic of retribution. If lament pressed the borders of linguistic expression and actual comprehension, the escalated response metthe anguish of lamentation demands, but no response can ever fully satisfy. The call to pride, and even content with being Jews, was somewhat tempered by the calls to save the warriors defending those highly militarized geographic boundaries, as much as boundaries of expression.

The boundaries of Israel as a “state” had become not only embattled, but less defended lines than firm fences, rigid, and asserting a statehood removed from negotiation, and perhaps from Zionism, as they were understood as bulwark against Palestinian expansion that so tragically ended with the battery of hundreds of ground-to-air rockets forms the long-barricaded Gaza Strip, serving as cover for a bloody invasion of Israel planned for a decade, approved by Hamas leaders in 2021–even known by some of Israel’s intelligence forces as code-named “Jericho Wall,” an attack of unmanned drones to disable the surveillance towers along Gaza border wall, to attack military bases, but dismissed–if it was also feared to constitute “the gravest threat that IDF forces are facing in defending [Israel].”