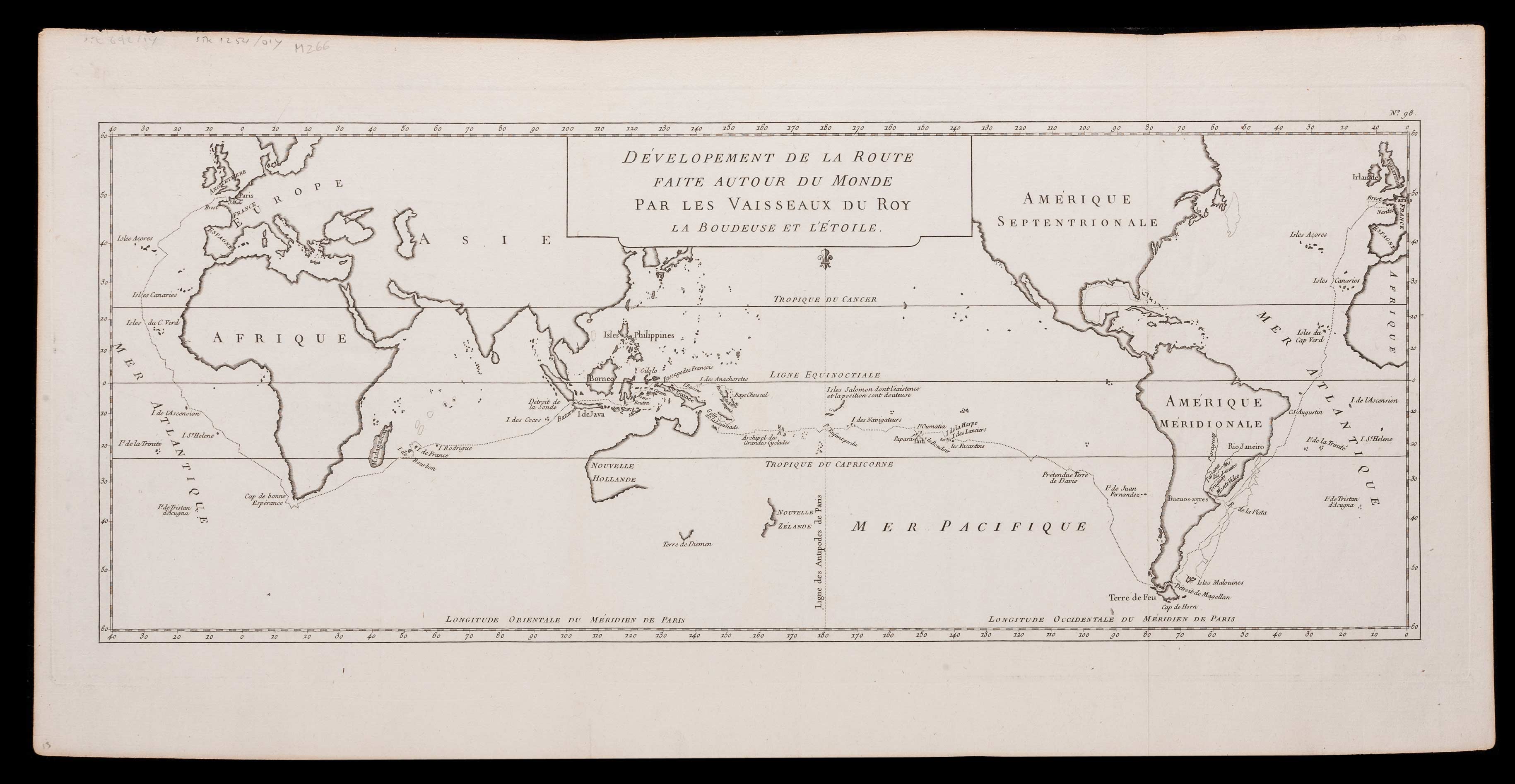

What is one to make of the silkscreen prints Hong Hao assembles from digitized versions of antiquated printed world maps? While dispensing with anything like an exact correspondence to the world, each creates a fantasia of borderlands, and offers something of a wry response to the frustration at imbalances of globalization, as much as they appropriate antiquated cartographical conventions and forms. Hao’s silkscreen prints manipulate scans of older global maps, he’s argued, as a set of confines or parameters to draw the world in new ways, but in doing so deploy the conventions of mapping to empty the familiar authority of the conventions of cartography. The huge success of his production of world maps in the series Selected Scriptures, which this ambitious and eclectic printmaker began in the 1990s, but dramatically expanded after 1995, have reached a demanding public. Is there appeal how they question how we see nations as best described on a map as they make foreign–and winkingly poke fun at–the authority of the print map as a register of the nation-state or territorial boundary lines? Or does it lie in the special appeal of their static form, presented as a classical sewn binding of an encyclopedia, in an age when most of the maps we use are downloadable networked media? In an age of online and digitized maps, Hao seems careful to design the sequence of maps as situated and constructed forms, that open to the viewer in the site of a stable book.

But the maps that he produces also chart an increasingly globalized world, no longer subject to the confines of antiquated or inherited cartographical forms he creatively has appropriated, and seem to gesture to the construction of a warped world of a less clear balance of power or status quo, concealing many unseen networks of financial exchange or political relations. The introduction of corporate logos, upbeat slogans, and fractures of linguistic translation into the imaginary corpus of maps Hao has produced with astonishing invention and rapidity question not only the hold of the power of maps but the medium of mapping, by dislodging the conventions of mapping from a familiar story and by suggesting the outdated nature of narratives of bounded territories and balances of power, as well as to indicate the increasingly skewed nature of global relations. If Hao has chosen the silkscreened image to be confined by antiquated formats of mapping, unlike the screens we use to view maps on hand-held devices, his crafted silkscreens take the map as a liberatory form to reorganize global space in something of a provisory or provisional fashion for their viewers to contemplate. In ways that dispense with notions of geographic correspondence or way-finding, and adopt the conventions of mapping to undermine western narratives, Hao distances us from paper Rand McNally maps in ways as appealing as they are successful on the international art market. In appropriating Western conventions for viewing global space, Hao surely comments on the power of mapping as a symbolic form and graphic practice, if only by undermining and defamiliarizing the coherence of the map as a record of familiar territory: not only do his silkscreen prints mutate forms of mapping, by altering names, locations of countries, color-schema and mirroring continents in wry ways, but adds weird arrows, graphs, and currents mark the ties of countries and continents. Rather than confusing the surface of the map, the direction of viewers’ attention to the map seem to reveal fractures and imbalances in the globalized world, even if in ways that seem to undermine–or question–the map’s own claims to reality, by releasing the map from claims of accuracy or indeed truth-claims.

The appeal of these images among his other attempts to synthesize an eclectic variety of scaned brightly colored objects from everyday life seem quite distinct. For not only do they indulge in the translation of maps to Chinese culture (and a global art market), but they raise questions of how all maps are translations of reality in ways that are comforting in an age of the web-based map. If Hao severs the map from claims of precision or forms of way-finding, he rehabilitate antiquated structures of mapmaking, now somewhat foreign to our period eye, to orient us to the impossibility of proportional mapping in a truly disproportionate globalized world. The images Hao defines are extremely popular as a sort of response to the failure of globalization, and indeed the failure to create a new map of the modern world. The sustained return to the map as a medium seems quite unlike the numerous ways that artists have long referenced the authority–and formal objectivity–of mapping as a register of the political status quo, in how they question the vision of global unity that maps and politics that maps have so long bequeathed. For if Hao uses the palette of mapping as a clear set of constraints to in Selected Scriptures, an inventive sequence of silkscreen prints that create revisionary maps of the world’s countries, begun from 1992-95, dismantle the oppressive presence of the map in our world to question the new hybridization of map making by moving it out of a “western” art. There is a sense for many art critics of a Duchampian inspiration; each seem to announce “This Is A Map,” or maybe even “This is a New Atlas” as a ready-made form. Hao reached back to the conventions and forms of printed Rand McNally-esque mapping forms–if not an earlier cartographical sublime–appropriating the claims of novelty and reduction of information as an elegant and economic statement of truth to make an artifact that lies between found objects and the “ready-made,” even as his final products seems to satirically advertise their own cheapness and untrustworthiness as a vehicle: the translation of the format of mapping in much of these works not only undermines its authority, but suggests an impatient and persistent attempt to find meaning in the map.

Hao’s sequences of silkscreen prints chart dystopia in faux open pages of an imagined traditional thread-bound Chinese encyclopedic text–as if to create the fictional broader corpus of which each form part. While they do not pose as recreations of an actual experiential world, they seem to comments on the mapping of the world that have particularly pressing urgency to the material presence of the map in an age that is increasingly online. Hao’s work, including imaginary pagination from the encyclopedia of knowledge from which they ostensibly derive, register glimpses of an atlas that charts the oppressive nature of global divisions, or an imagined atlas of the social construction of space, if not of an attempt to start dialogue with a “new world order.” The prints appeal s a way of romancing the hand-made map, in an age of the web-based maps and a surfeit of digitized data, however, by recycling such foreign, if familiar, conventions of printed maps to orient the viewer to a disorienting world. In place of the data visualizations that chart the process of globalization, Hong’s recourse to screening maps to show inequalities and disparities seems by no means accidental. For Hao takes the map’s surface as a field for further manipulation: the world seems an open book, in the silkscreen prints shown below, made after the original series, and use the cartographical surface as a charged field for modification, inversion, and inscription, adopting the abilities offered by digitization to create a mock-permanence in his prints.

Take two examples. The very mutability of the medium of mapping in his work suggest not the tyranny of modern mapping, but the provisory nature with which maps translate space for their viewers, and the indiscriminate nature of how they present global inter-relations as a space that can be read in “Selected Scripture, page 1999, The Memory of Millennium” (2000). If all maps are translations, these are quizzical ones, as much as physical ones–filled with corrections, misprints, and ways of subverting their own iconic authority as maps, and glimpses of an imagined atlas of a nonexistent world.

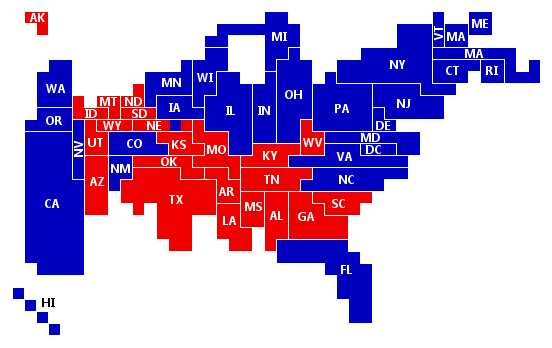

In the first, the excavated distorted “North America Ocean” and “South America Ocean” are dotted by odd arms and insignia, their actual confines warped to create imagined lakes and emblems of airplanes and Microsoft, unlike the “Asia Ocean,” and oceans become land mass.

In the scanned maps Hong has altered and manipulated, America might be expanded, renamed as the PRC, Asia folded into obscurity save Japan, and Canada foreshortened into a swelling United States, all to upset viewers’ expectations for reading their surface, which he reiterated in “New Political Map, 2” (2000), “New Political Map, Which One” or “New World No. 1” (2000), repeatedly playing with the constraints of mapped space in ways that not only skew actual relations, but invite us to recognize the arbitrariness with which we map our mental space or are accustomed to do so.

Hong Hao was trained in printmaking, and values the medium of silkscreen prints as versatile tools not only to sort objects and create catalogue, but to treat the map as an ordering device. The series of Selected Scriptures, which are distinct from much of his work in their ostensible unity, are distinct from Hao’s interest in sequence of assemblages that are characterized as mosaics of found objects, for the maps he has invented are anything but disinterested collections of visual information or compilations of objects. Hao’s sharply observed maps are not aestheticizations, so much sharply observed post-modern satires, and comments about the recoding of information systems and the processes of the translation of information that occur in maps. In his powerful series based on the clever appropriation of older maps, the antiquated nature of the maps allows them to be treated as a new expressive field. For Hao’s Selected Scriptures (1992-2000) seems to ask us to about the role of visualizations in suggesting the global imbalances of networks of power often removed from actual terrestrial relations in an our over-mapped world, treating the map less as a totalitarian constraint or a set of fixed conventions than something like a musical piece that could be assembled, varied, and reorganized in sharply provocative ways. Hao has created skillful digital transpositions of world maps in his silkscreen on heavy wove paper, as if to recall their craftsmanship and artifice to contrast to the mechanical reproduction of serially produced maps of topical concerns. The contrast of materials of their subject and handmade production recall the power with which printed maps once assembled the lived world, in ways that masked all its inequalities and absence of proportions, working within the structure of the maps to undermine their content and reveal the very inequalities that they concealed. Hao has claimed to be especially attracted to historical maps as being “capable of inspiring ideas on what we take as common knowledge” and as “almost the most direct and most economical way to know the world.” But the economy of mapping by no means limits his variation of his range of artistic expression in this series: Selected Scriptures exploit this economy of graphic expression and its organization as an inspirational guide for playing with their formal transcription of space, redeploying the map as a new arrangement of space in works that bear such self-titled silkscreen prints as “Latest Practical World Map,” “New Political World,” or “New World Physical“–to cite the prominent English typeface in his Selected Scriptures series.

Several of Hao’s set of maps, which appear below, capture the promises of how maps make new claims to organize the world’s totality in readily legible ways that make us look at maps in new ways, alternately whimsical, quizzical and ironic look at space. In an age of online and digitized maps characterized by the near-constant mapping of financial transactions, geographic locations, and activities, Hao’s images are less about “found” maps than the rediscovery of the assembly of space from digitized images maps and varied map detritus that he wields and transfers onto his chosen medium. For he has adopted the particularly copious formal syntax of mapping, preserving the appearance of cheaply printed maps that he emulates, to ask how successfully maps might ever translate an image of our world, subtly reshaping their economy to upset their meanings–evacuating the map of any sense of wayfaring tools, but enriching its symbolic form.

1. The formats of mapping that Hao appropriates are, of course, removed by several generations from our own notion of map-use or the medium of mapping in modern life. If it is increasingly confusing how to orient oneself to an increasingly imbalanced world whose inequities have been put on display in how news media often ignores most inequities in the inhabited world–not to mention the disproportionate threats of global warming to ecosystems, regional economies, and global food supplies–Hao assembles more light-hearted–if deadly serious–maps that invites us to engage the mystifications on maps. Artists have long worked with maps. But rather than offering an aestheticization of the map’s surface, as Jasper Johns, whose re-used the familiar image of the names of states in the United States, repainted to transform a well-known image, converting familiar conventions of maps to encaustic, in an etherial blurred space of dripping paint that obscured clear lines of legal divides, and render the conventions of four-color mapping a ghostly haunting blur rather than a symbol of space–

–Hong Hao actively remakes the surface of the map as a map. And his works demand to be taken for that reason as maps, or at least as interventions in practices of mapping, rather than images that appropriate cartographical images, conventions, and signs.

Hao’s maps map, of course, a globalized space as a space into which the artist makes his own interventions, although his work is in ways resonant with Johns’ evacuation of mapping forms. For Hao’s maps re-assemble the disparities and tyranny of the globalized (over-mapped) world. The disparities within the global economy has the danger of being recapitulated, of course, in ways that he lampoons. The collective atlas that he imagines, which collectively run against the global maps we carry around in our heads, or the maps that we use to try to come to terms with unimaginably complex implications of global military constellations and warming processes. Already, in a work that predates the Selected Scriptures, Hao’s “The World Distribution of Guided Missiles” [sic] (1992), a monochrome silkscreen print replete with the mythical beasts and figures that recall the figures on medieval portolan charts for ocean travel, shocks us with the explicit charting of state secrets. It also suggests a new playful engagement of the map as a communicative form, even as he works to expand the boundaries of a map’s informational value. When he locates the bulk of guided missiles in Antarctica, the effect expands the map as a record of inhabited space, repurposing of the cartographical iconography with which he knowingly plays: in this map, the effect is oddly to diminish the appearance of the world’s size: at the close of Operation Desert Storm, of Gulf War, and the inundation of airwaves with images of US fighter jets on a sustained campaign of aerial bombing more extensive than expected, and provoked counter-attacks, Hao imagined the world as cowering from missiles poised for launch in the “World Distribution” silkscreen i seem to translate the cheaply printed paper ink map into his own image that magnified China at its approximate center. As much as translating western cartography into a new art language of classical Chinese origin, Hao seems to confront the difficulty of mapping power in this and his many subsequent silkscreen prints.

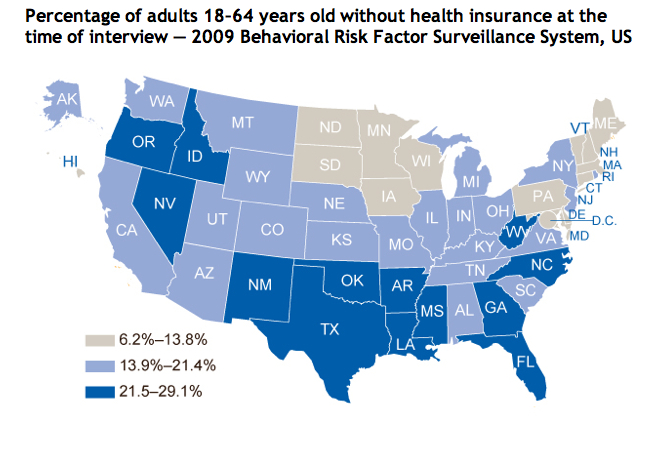

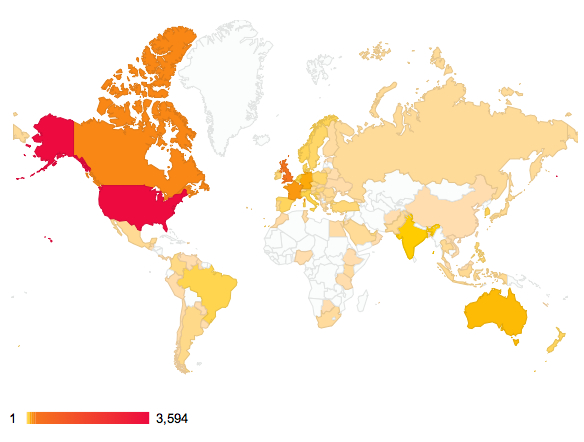

The disproportionate prejudices in these maps are well-known. Global warming, a concept few can claim to understand, is also the, most mapped–if perhaps most disproportionately mis-mapped–is repeatedly wrestled with in a variety of maps that try to lend the process a concrete appearance. Despite the fact that 40% of the world’s population lives within sixty miles of the shore, and 200 million people live within five meters of sea-level, the disparity of the dangers of shifting shorelines that are poised to shift dramatically with global warming are only partly evident in an interactive “Global Heat Map” produced by the Union of Concerned Scientists: and the extreme dangers that the shifting shorelines poses for low-lying countries is by no means limited to the United States, even if this sometimes seems the case in our own news media or the relative blindness or radical shortsightedness government working papers on shoreline sensitivity–subtitled “American Starts to Prepare–on the impacts of global flooding of low-lying lands. (Even if there are exceptions in American media publications.) The deepening disparities of our own mental maps–evident in the apparent perplexity that one out of six Americans in where in the world Ukraine is located, according to the Washington Post, which almost makes one wonder if the survey was credible or if it generated sarcastic responses–the lopsided maps we contain may make Hao’s imaginary corpus of lost maps apt commentaries on global inter-relations, as much as a formal syntax for creative expression. But they grapple, if in a light-hearted way, with the problems of mapping the globalized world.

2. Hao’s work is a retrospective recreation of a cartographical sublime that reaches back to a lost medium of paper maps. The particular productivity of mapping as a new form of invention in Hao’s work from the late 1990s, suggests a particular neat coincidence of how maps speak to power, or power through maps, that interestingly mirrors the growth of online mapping: although Google Maps was only launched just less than a decade ago, in 2005, shortly after Steve Coast created a free, editable map of the world, OpenStreetMap, based on Wikipedia, in 2004, the first online mapping service, MapQuest, If OpenStreetMap responded to the inability to freely download government-run and tax-funded projects like the Ordnance Survey in England, as these mapping projects have expanded, the epistemic remove of maps such as those that Hao uses–and the apparent chronological distance of a map created by silkscreen, but belonging to a printed encyclopedia bound as a classical Chinese book–gains new appeal as a rehabilitation of mapping as an aesthetic medium and as a tool for imagining and locating geopolitical abstractions. Unintentionally, the rise of GPS and geocaching as modes of map making, satellite imagery, digital searchability, the branding of Google Maps and the Google map viewer, and dramatic expansion of use in over one million websites of the Google’s API, have conspired to so remove the five-color map from our “period eye”, that its epistemological antiquity may be increasingly difficult to distinguish from the thread-bound classical encyclopedia Hao’s Selected Scriptures referenced. (Google’s corporate logo is absent from Selected Scriptures, but the presence of Internet Explorer and other corporate insignia suggest a need to locate the web-based map on the borders of what we once new as the world’s inhabited territories.)

Yet the weird notions of contiguity of a flattened earth that Google Maps has perversely re-introduced–reinstating a continuous block of Eurasia and Africa, for example, isolating China, Australia, and North America–mirrors the oddness with which Google Maps has rehabilitated its own variant of the long-discredited and cartographically retrograde biases of the Mercator projection, a handy solution to the flattening of the earth’s surface to coordinates of straight lines of latitude and longitude but which amply distorts its surface, irrespective of actual land-mass, but whose convenient centering on Europe provides the basis for all Google-derived web-maps. (China’s role in this internet society is contested, with most social networking sites banned in the country, including Facebook from 2008, Twitter from 2009, and Google+ as it was introduced–despite relative open-ness to LinkedIn, reborn in China as 领英, pronounced “ling ying”).

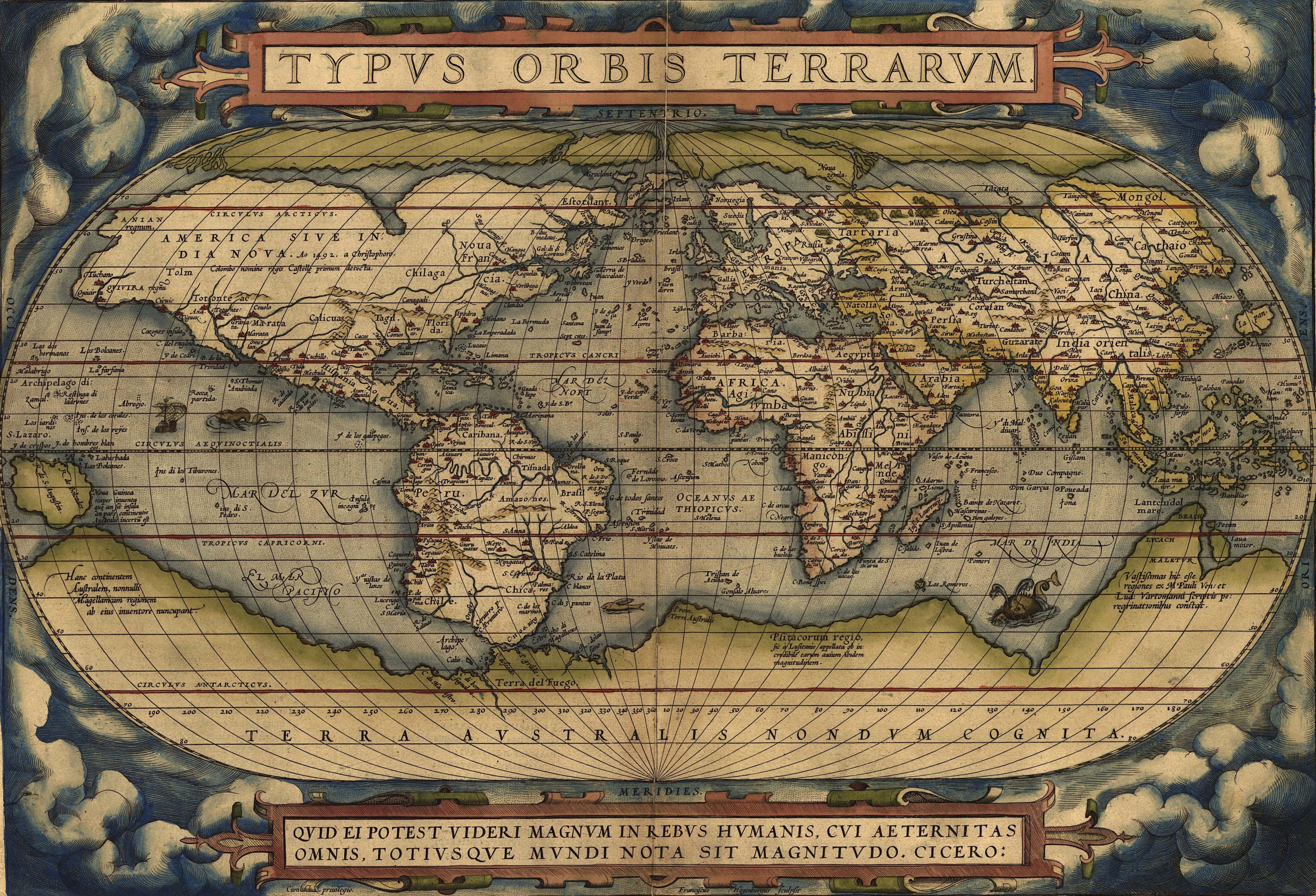

For all the personalized coziness of the Google Maps Navigation, Google Street View, or My Maps, this close variant of the quite retrograde Mercator projection has perpetuated a primarily targets that Hong skewers as a frozen model of global relationships of power, which is striking for how it eerily corresponds to Hao’s “New Political World” (1995), whose evocation of the modernity of rewriting the world’s geopolitical structures is not only reminiscent of the early modern cartographers Mercator or Ortelius–the former’s “Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendate Accommodata” [“New and more complete representation of the terrestrial globe] properly adapted for use in navigation]” of 1569 and the “Nova totius terrarum orbis geographica ac hydrographica tabula . . .” of 1570–but also to announce new political configuration of landmasses in relation to one another. Although Hao didn’t prominently include Google’s logo among the logos of international corporations in the sequences of maps he has designed from 1995, his work succeeds by upsetting our Westernized confidence in mapping, more than playing with cartographers’ formal conventions.

And if Ortelius prided himself on drawing national boundaries and distinguishing the world’s expanding number of continents, Hao’s silkscreen prints take pleasure in redrawing boundaries, reconfiguring the shapes of countries, and shifting and switching toponyms, as if to describe a world less defined by boundaries than the continued symbolic authority that maps have long continued to exercise. Indeed, rather than accessing or retrieving data in the format of a map, we are presented a map in the legible form of an open book and private space, even if we are invited to imagine the audience of readers for whom such a map might be mechanically reproduced.

The maps are forms of imagining a conscious redesign of the balance of power and populations that antiquated static maps once mapped. Indeed, Hao’s reassembly of the map may as a form of memory might even recall the famous translation of the Ortelian project in 1602 by Matteo Ricci, working with the astronomer, mathematician and geographer Li Zhizao (1565-1630), who engraved it, in ways that affirmed the dynamic and interactive nature of the actually static nature of a woodcut print map. (Although Hao may not reference this famous notion of cartographical translation, his appropriation of the format of world-mapping seems to intentionally reverse the trajectory of Ricci’s importation of cartographical iconography and place-names on a somewhat comparably busy and densely crowded symbolic field.)

Hao’s subversion of western mapping as a national political tool is often too crudely cast as reaction to the western–and American–dominance of constructing the world map, and an incorporation of traditional cartographical tools within a “Chinese” art. This is too simple, and too readily essentializes “western” and “Chinese,” and where these works of art lie in relation to map making as a craft–or how Hao’s art relates to the currency of the mash-up as a map. For Hao works with antiquated maps–indeed, making maps, rather than than only find them, to play new stories out on their surfaces–and indeed its distance from the imbalances of authority in our geopolitical world. Reading the surface of the distribution of political power in the eponymous “New Political World” (1999) in the Selected Scriptures project playfully inverts the notions of legibility to demonstrate a balance of power regularly elided: the playful projection of geopolitical values is exploited to present a new way of reading a familiar demarcation of terrestrial expanse divided by naturalized boundary lines, playing fast and freely with some of the iconography from news maps or other cartographical images.

If we love to read maps to move across space, and cross frontiers drawn in space, the shifting toponymy and place-names that we encounter in the imaginary Atlas of Hao’s device opens up a world we’re sad to read but that we can at the same time also recognize as something that the anonymous mapmaker has synthesized. Hao’s work suggests a uniquely hybrid creation, as well as a satirical relationship to the Rand McNally political atlas, which seems its primary target at first. Hao, who graduated from the Beijing Academy of Fine Arts the year of the suppression of protests in Tiananmen Square, has specialized in transposing digitized images to silkscreen prints that skew the actual geography of the world in his prints, much as they play with the reproduction of five-color maps in print culture with the format of an hand-made artist’s book, but derive from reproduced images scanned, digitally altered, and reproduced as silk screened images, linking traditional crafts, the Cultural Revolution, and modern digitized media to deconstruct and repackage (or redeploy) the map as a political statement.

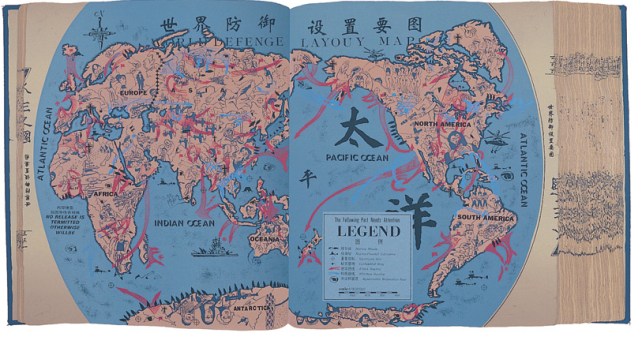

The weird translation of cartographical images is part and parcel of the project, evident in the irony of the most “accurate” map in the Selected Scriptures, the “World Defenge Layouy Map” [sic] (1992), a variant based on Hao’s earlier 1992 work:

Hao’s new map of nations illuminates military power by relatives geographical sizes of nations to reflect military power, recycling the map as a metaphor. As much as it suggests a cheap reproduction, with its title seems suspiciously printed in uniformly spaced letters, the image of a “new political order” is meant to dislodge our expectations for reading a map centered on t: and on the map, although the pathways of world travel include a sailing junk, but are dominated by fighter jets among large pinyin characters that immediately strike a western viewer, and reminding us that all maps are both constructions and translations and that, indeed, the power of the map in part lies in its success in translating reality to a seamless whole. In Hao’s Scriptures, the integrity of the map is disrupted by the shifted orientation in the digitized images of names, landmasses, and pastel hues, as if to recall the mass-produced posters on cheap paper that recall Maoist times, the upbeat candy-colored pastels worthy of PAAS Easter Egg paints rather than a five-color map. They describe a scary surface of disproportionate global powers, with the PRC at their center, now straddling the Atlantic and Pacific, whose places are oddly reversed, as if one emptied a Rand McNally map of toponyms and reshuffled their location, as if to mock the faux disinterested nature of maps from the perspective of the current PRC, which finds itself somehow between the Atlantic and Pacific, in the place of North America, an expansive Israel to the North, and the United States displaced from its position of power:

3. Artists have been making maps–or using maps to make art–since before the first printed atlas, if not since the first globe. But Hao takes the map to excavate it of meaning, and ask about the oppressive world system we have inherited, playing with the oppressiveness of that system and the almost light-hearted pastels of artificial colors (pink, yellow, orange, blue and green) we use to divide the inhabited world in printed maps to suggest that the map has little bearing on it. The odd remoteness of the historical map offers a “tool to think” that exposes the discrepancies of our mental maps of geo-bodies. Hao all but ignores the actual geographical contents that are the ostensible subject of a map: and as the project progressed, the maps he creates have an increasingly ironic organization of space. Reading the surface of the distribution of political power as referenced in the eponymous “New Political World” (1999) plays with notions of legibility that are regularly erased or elided within print maps, but seem especially pregnant with the distance of time: the playful adoption of the map’s projection of geopolitical values is exploited in Hao’s work in order to present a new way of reading a familiar demarcation of terrestrial expanse that is divided into naturalized boundary lines, playing fast and freely with some of the iconography from news maps or other cartographical images: Hao’s map of nations illuminates military power by relatives geographical sizes of nations to reflect military power, but even its title seems suspiciously printed in uniformly spaced letters: and on the map, although the pathways of world travel include a sailing junk, but are dominated by fighter jets among large pinyin characters that immediately strike a western viewer, reminding us that all maps are both constructions and translations.

The power of the map in part lies in its success in translating reality, so that the PRC now occupies where we expect the United States:

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The humorous reconfiguration of space in these maps transpose space and place with a flighty flippancy foreign to any actual land map. Why is Hong Kong now at the mouth of the Mississippi, in the place of New Orleans? The legibility of the rest of the world is almost made ridiculed, not only as the ocean off of what seem Alaska’s shores is labeled “Atlantic Ocean,” but since the region is actually Uganda, nestled beside the newly bordered Israel and Chad, creating a perverse geopolitical world that seems an absurdist collage of what might be: as the People’s Republic of China now occupies, save in Florida and parts of Norther California, most of the land that one might associate with the United States; to the north, Israel lies lazily across current Canada; London is dispatched to the South Pole; Canada is relocated to a strip of diagonal land in Eastern Africa, beside the Indian Ocean; Europe divided between Vietnam and Mozambique as if their names are dislocated from the geographic fields in which we are accustomed to find and locate them.

Hong Hao all but ignores the actual geographical contents that are the ostensible subject of a map: and as the project progressed, the maps he creates have an increasingly ironic organization of space. Many of Hao’s works trumpet their modernity in analogous, if tongue-in-cheek fashion–“The New Political World Map” (1995); “The New World Survey Map” (1995-96); “The New Geographical World,” Selected Scriptures p. 3085 (2000)–as if they offer windows on a newly registered reality to readers. Is ‘place’ less of a signifier, in the map, than the global distribution of power? The sizes of countries are ordered, not only in terms of the military and economic power of nations, but in ways that upend the semantics of the legibility of space, despite the familiar color-scheme. The result is often a fairly scary image whose totality one pays far more attention to, decoding the configuration of countries and assessing their sizes with an eye to power perhaps far more than geographic relationships, which are–witness the fighter jets–of far less import today. The clearly cultivated flimsiness of a mistranslated map, standing askew to the actual world and placing Asia at its center, pushing mirror reflections of Europe to its margins, and dispensing with America, in ways that not only skew spatial relationships but show the reproduced map as a field for staging imbalances of power.

National Gallery of Canada

“Selected Scriptures, p. 1999, The Memory of the Millennium” (2000) assembles a grab-bag of cartographical inventions around an inversion of land and water, so that oceans that connect and separate continents now seem landmasses: as if to exploit the map not only as construction, but assemblage of cultural artifacts that desperately press space into readily legible terms, Hao presses the fertility of the format of the map as a signifier into his service to new extents: emblazoned with the prominent descriptive legend “New World Physical,” the map is difficult to orient oneself to even more than his earlier work, its oceans (NORTH AMERICAN OCEAN; AFRICA OCEAN; EUROPE OCEAN) erase landmasses, as if to repurpose this most conservative of media so that where once lay land, oceans are overburdened with objects. Weird graphs erase any familiar promise of the legibility of mapped space. The didactic iconography of educational maps becomes a repository for graphs, varied iconographic detritus from warships and the logo of internet explorer:

The playful array of translations in the map–both translations among mechanical processes of reproduction, and contexts for viewing maps, as well as translations of map-signs, conventions, and toponymy–play with the “novelty” of the map and its antiquated medium to make a new material object for readership. By using a base-map, scanned from a four-color map of Westernized derivation that seems printed on foolscap typical of the posters of the Cultural Revolution, which Hao cast in the form of a traditional hand-made book in a set of individual silkscreens, as if it belonged to a corpus of lost maps in the Chinese tradition, rather than informed by Western cartography. We are a far cry from the Eurocentric “Map Translator” functions, if the adherence to a cartographical structure and the color-scheme is oddly familiar: Hao takes the the levels of translation, indeed, in a much more playful and wryly sarcastic direction that exploits the almost generative fertility of the proliferation of meanings in mapping forms, that consciously reveals the power of mapping forms that are left as a neutral backdrop in the image that uses the Google Translate API. To be sure, unlike the Google API, the maps Hao crafts, if in their collective dizzy the viewer in percussive ways, rather than retrieve or access data, present a fixed tableaux.

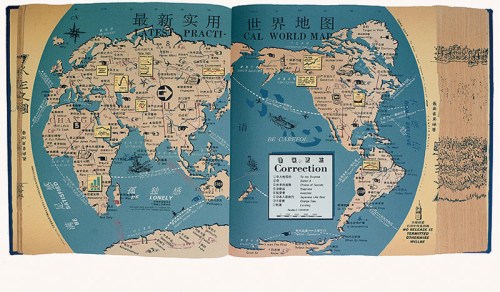

Some of the other imagined pages Hao designed from Essential Scriptures of 1995, as “Latest Practical World Map,” manipulate and lampoon the sense of practicality of a map, even as they introduce emblems of consumerism as much as militarism within the map the maps themselves, in ways that play with their surfaces by renaming continents so that countries, continents, and cities are no longer recognizable, hydrography abstractly symbolized and an eery globalism illustrated in the surface of the map itself–and slogans such as “Be satisfied” or “Be careful” will later give way to those of free market neo-conservatism, from “Control, gain, own, exploit” to “Fame and fortune: you can have both”: these maps have been compared suggestively to a traditional Chinese landscape in which the manipulation of the conventions of landscape become a register for a subjective state of mind, although in Hao manipulates conventions takes aim at their ostensible objectivity, and indeed the images of globalism they present: the conceptions let silent in the map are used as commentaries on mapping practices, or on the concepts of globalism. Or, the map becomes a surface for an almost random generator of slogans and injunctions–“BE SATISFIED,” “BE LONELY,” “BE CAREFOL,” “DON’T BELIEVE,” “BE LONELY”–that suggest the alienation of its viewers. Whatever constitutes the practicality of a map, the combination of odd translations, even odder graphs, juxtapositions of slogans and generic injunctions uses the historical remove of the map-as-image and inscribed surface to puncture its utility and authority, and point up some of the odd ways of reading truth into maps.

4. What, indeed, constitutes practicality in a map, and how is the translation of the world to “practical” terms defined? Practicality suggests that it offers ease of ready consultation by readers, but we find a surplus of significations that mimic many maps in their almost distracting quality. Many of the slogans that are on the map–“NO RELEAE IS TERMITED OTHERWISE WILL BE–subvert any sort of reading for sense. Indeed, Hao’s intentional layering of odd translations (BE CAREFOL), odd graphs, juxtapositions of slogans and generic injunctions uses the historical quality of the map-as-image to puncture the very notion of utility, and point up some of the odd ways of reading truth into maps.

Hao’s “New World Survey Map” engages playfully with the ways maps symbolize the proportionality of space in powerful ways, reduced Asia, as it magnifies Japan, but shows the globe wonderfully distorted with the magnification of Europe and America, in a playful accentuation of the disproportionate distribution of weapons and political influence. Or is this the image of the political order that the West–or an exaggerated and hugely magnified Europe and [North] America and Japan–purports to create and legitimize at such political organs as the UN Security Council? In the below map, the “legend” is of little help, but the map says enough, shrinking oceanic expanse and magnifying countries that are bloated in the disproportionate attention that they receive from news channels, or in international political bodies, as if to render a map based on their prominence in a world historical record or online news-sources:

This utterly “othered” “New World Survey Map” (1995) punctures the hegemony of the map, and stubbornly it refuses to relinquish the truth-claims of a map: if the westernized cartographical tradition to diminish all Asia save the Japanese, which it so greatly magnifies.

5. The invention of re-inscribing the cartographical surface in these silkscreen prints provided Hao with a particularly rich vein of production among his varied projects, and one that met a large audience. “New World No. 1” (2000), Selected Scriptures, p. 2001, contracts the known world to a scary picture of three imagined continents or landmasses, surrounded by warships, arms, and satellites that suggest their military might: where the Typus Orbis Terrarum is a contraction of Eurasia and the United States, who bracket the vastly expanded island of Japan, improbably raised to the status of a Superpower among them, and only a hint of Antarctica to the south. America is emblazoned by iconic “lounging ladies” between Las Vegas and Texas, this map is emblazoned by the odd emblems of progress from the ancient Skylab to Internet Explorer, as if this “New World No 1″‘s order were antiquated already, its seas haunted by blueprints of jet fighters or warships, inhabited surface surrounded by satellites circulating its perimeter, as if floating in outer space.

The image of a new book of world history and global powers is particularly powerful, not only for disturbing the mapping of a stable geopolitical orders that maps perpetuate, in a sort of inversion of the Peters’ projection disturbed our preconceptions for seeing the world as imitating or mirroring a political order, but inviting us as viewers to make and remake the maps that perpetuate political orders and biases in our minds, and how the an atlas for a disproportionately under-represented world might be renegotiated by its readers. The reproduction of these cartographical orders of representing global powers becomes a sustaining theme in Hao’s work, so infinite and unending is the variety of silkscreen maps that he produced, almost haunting by the disproportionate images of the world and by maps as the flimsiest of representations that continued to be accorded a significant weight for so long: the map is lampooned as a reproduction, albeit one with deep westernized connotations of arrogating claims for totality to itself, while presenting a diminished image of what it purports to map. Indeed, the flimsiness of its reproducibility is evident in the difficulties of its translation, laden with “corrections” and odd graphs seem to record the map’s remove from the viewer, lampoon the tyranny of its own absurd assertions.

6. Hong Hao is by no means alone in questioning the inheritance of mapping forms. His work is evocative of Ai Wei Wei’s interest in the hybridization of Western commercial logos and ‘traditional’ art forms, apparent in his powerful statement of the naturalization of his “Map of China,” (中国地图) (2006). Ai Wei Wei’s work that might be said to literally translate a map of the frontiers of China into the stolidity of a classically Chinese material–wood of Qing dynasty temples–that might be verging on sacrilege. The “map” suggests the consolidation of the official map of China from fragments of the past, as much as a terrifying isolationism, unlike Hong Hao’s odd global refigurations. Yet Wei is far less interested in the symbolic conventions and legibility of the map than what might be called its iconic form–even if his work indulges in some of the same questions of the synthesis of old materials and practices with modern symbolic forms, and the translation of maps to new media.

Yet rather than present the “fantastic and absurd” world “governed by violence and greed,” Ai’s art-map forces us to find the map in and that is refigured from it, even as it asserts the isolation and frontiers of the unit of the Peoples’ Republic of China, as if a continuous tree trunk. In translating actual geographic frontiers to something that looks like it emerged from a 3D printer more than a map, Ai Wei Wei invites viewers to linger over the shifts in shading on its face, even as it distances the map as powerful construction, emptying the stale medium of the map of its stale symbolic authority by translating it to another medium: in the above, the PRC is fashioned out of Qing dynasty wood; the below, out of recycled cartographical imagery.

Both images ask what sorts of opaque surfaces, rather than mirrors, something like a map creates. But perhaps the playful irony of distancing any of the positive associations–if any still remain–from globalism in a more engaging view of the legible conventions of a bounded map, Wei comments on the fetishization of the form of the map and its delineation of naturalized frontiers. Hong Hao’s work seems more engaging, and more familiar, because it speaks more incessantly to our own habits of reading of maps, and the increased business of the making of the map’s surface as a format that increasingly unceasingly begs to be read and re-read. Hao returns us, with comfort as well as to produce considerable unease, to the reading of the map’s surface, making fun of its transparency and referentiality at a time when online maps dispense with claims for transparency or signification that now seem to be artifacts of letterpress typesetting or print. Hao’s maps recall objects of serial production–and he indeed seems to be serially producing such artifacts for an eager art market–in ways that recall habits and formats of reading space that are in many ways no longer accessible or familiar, but which register the difficulty of the possibility of undertaking an ethical mapping of the inhabited world. Not connected, and not networked, Hao’s almost serially reproduced maps gesture to the translation of the authority of the static map from another time. Rather than offer images delivered by the screen or accessed remotely, even if he does not think so, Hao’s maps translate back to western eyes as cartographical eye candy and comfort food.