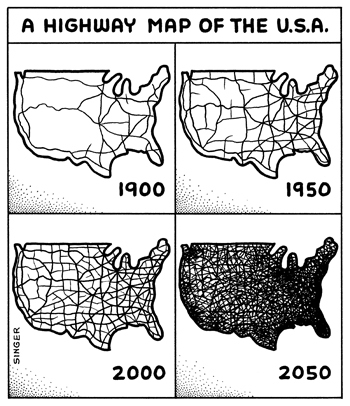

In a world where much inhabited land has become paved, and indeed where paved roads interrupt habitat, ecosystems, and formerly open land, the icon of the America license plate has perhaps rather unsurprisingly become a token of a bucolic sense of place. The images on license plates are not perhaps intentionally advertisements for travel, but often appear to be–from the designation of Oregon as the “Pacific Wonderland” to the promotion of California beaches as a perennial sunset, lined with palms, or Florida as a site of admittedly man-made orange groves.

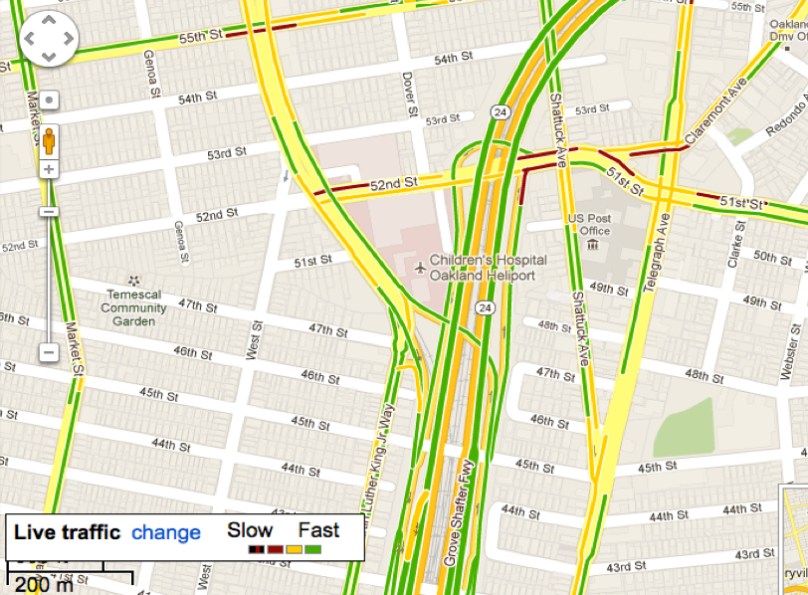

If cars offer a bit of a billboard of the driver, my own adoptive motorized state of California set a new standard for defining itself by wonderful license plate designed by California painter Wayne Theibaud as an arts plate specially designed to represent California, “Coastline,” whose iconic design of a beach, palms and setting sun in a single panel have funded arts education programs premiered in 1994–the license plate whose sales and renewals have generated over $74 million for the California Arts Council, as “Coastline” is a perpetual gift to his adopted state set a standard publicizing California’s ability to offer artists assistance by a dedicated website for license plates! The sun-drench he’d optimism of the world-view of Theibaud seemed to be distilled, reframed from a painted panel to nestle within the rounded curves of the license plate, the neoprene colors of a sewing sun seemingly a gesture the surfing culture of the coastline that was being depicted–the image was called “Coastline,” even if this was not the entire state–as if offering anyone a utopic view of the state’s riches on its Pacific Coast Highway, a site of intensely scenic traffic in the state, if the volume of traffic on Highway One, or PCH, is pretty hard to determine, and varies dramatically with road closures due to mudslides, fires, and vehicles.

If Theibaud’s work is far more often exhibited in museums worldwide–as well as in Davis!–while other designers of license plates are less well-known, the shift in designing the license plate as an alternative map of automobile registration–and presumably its drivers residence–offers a unique way to establish place on the road, to stake a sense of location on the increasingly mobile crowded highways on which we travel, reminding ourselves of locatedness, even while we are on the road. If the late California painter Wayne Theibaud argued that ‘the best abstract painting . . . is one that comes from something, but it may not be evident,’ calling its process an invitation to ‘speculate and paint the picture of your own devising.’

The experience of driving down coastal California is evoked by and seems to have inspired the license plate he was commissioned to designed to fund state art education programs, the abstract forms of the painting also inspired the artist to make a statement of the power of pictorial arts– they now go for about a hundred dollars on eBay, so valued are they as forms of art of their own as an image which “captures the beauty of the California beach sunset,” evoking a place that we might have long considered, looking only at maps, something that attracts one to drive around, with an automotive experience of its own. While Theibaud probably didn’t only expect folks to study them on the highway, or from behind the wheel, the illustration of place from an abstract expressionist who indulged himself and his viewers with cakes, gumballs, and roadways offers an idealized if familiar driving experience, moving directly into a blinding setting sun with one’s eye on the road.

The neoprene palette that Theibaud adopted was familiar from his other word, and quite enchanting, transforming or mutating the everyday into an electric view of modern life that let us see the quotidian with new eyes. (To be fair, while Theibaud was showcasing his California roots by that neon ocean blue and setting sun, he was only embraced as a California artist after having found less success in art markets outside the state, and after he became a carpet-bagger in reverse, rolling his canvases up into his old car and driving cross-country to find a New York dealer, with fellow-painter Mel Ramos. The road trip that led the UC Davis faculty member to return to be celebrated as a local pop artist led to the commission for a state’s license plate that expressed his deep concern with the public interest,–if not the most reproduced image of his pictorial corpus–confirming his status as a California artist, for whom California’s landscapes and cityscapes became almost staples of abstract expression, rather radically suggest one might best experience the place by car.

But the dayglo colors he indulged in the license plate whose setting sun is almost an abstraction, extending an orange horizon line that frames the vivid blue ocean and seems to intersect with Theibaud’s road, transformed dayglo palette into a sense of place, if it creates an icon of the state that privileged its coastal highways to Los Angeles, if not the Davis-San Francisco commute. The energy of the bright, open skies that distinguish the state is conjured by the bright colors of the palette that Theibaud, a former sign-painter, chose to express himself–

–are hardly similar to the colors one might find on a map, so much as Sherwin-Williams, but they convey an almost abstract idea of place, conjuring the coastline that was increasingly identified with California, as much as a basis to illustrate a specific landscape, or place: it is almost a state of mind. The frame of the license plate lay at angle to the actual color palette of spectacular coastal scenery the highway offered, transfigured through a Southern California imagination of an artist born in Arizona who grew up in Long Beach, who must have often commuted to the southlands; I’d bet was happy to ignore the bumper-to-bumper bottlenecks at either end of the expressway, despite rewarding views of the San Gabriel mountains as one enters LA, for a romantic coastal view.

Thiebaud’s pioneering work on metal is hardly the high point of Theibaud’s rich artistic career. But it prefigured the vast expansion of not vanity plates, but pictorial maps, or counter-maps to the maps we depend on to navigate roadways that allow us to meet our destinations. And in an age when the world increasing arrives to us in license plates in a way radically removed from the road, in short visual statements, the way that these pictorial images of an unbuilt site, distilling a purity of place on the license plate that rarely exists on the roads themselves. For if the highway offers an unfolding of space and landscape by which we promise to be endlessly entertained, it was no coincidence that Theibaud’s shore-centered perspective in Coastline dialectically generated, as if to illuminate other landscapes that it occluded despite its expansiveness, of mountain ranges–and even to enter the oceanic expanse of its coast–ocean water delightfully dripping off the tale of the whales offshore its coastal waters–in the so called “Whale Tale” plate of the California Coastal Commission–as a new sort of imperative on the license plate, transcending a landlocked place–

Whale Tale Plate/California Coastal Commission

–that oasertes the unique privileges of Californians as coastal residents by its injunction to dedicate ourselves to coastal protection as if driving on roads were compatible with a clean coastal ocean.

What is the recent turn to shift from vanity plates to license plates that bear testimony to our personal of world improvement? An unforeseen outcome of Theibaud’s creative design may have led many o to wear on your car, or encouraged privileged Angelinos to indulge options of alternative fantasy landscapes, indulging their own artistic skills on a broad cartographic take on the state, to model possibly more preferable to options the state offers, mostly modeled after screen shots of an age of iPhone tourism, that has helped reinforce a bounteous relationship to the land.

Reader-Submitted Alternate Landscape Design for License Plates, LA Times, 2022

Does the alphanumeric annotation born of computer texting suggest an origin for this image of Half Dome? Could Thiebaud have imagined unleashing the futility of self-designated artists to project alternative image of the state, having pioneered and opened the potential fertility of license plates as canvases? As if in reaction to Theibaud’s preference for the warmer colors of his coastline, the ranges of mountains rising behind the sea became a default alternative in recent years, or the most part, even in environmentally conscious variations to call attention to the mission of Keeping Tahoe Blue–substituting the treasured lake amidst snow-capped Sierras for the coastline of the Pacific–

–far starker and more angular than the smoothed curves of Thiebaud’s version of Margaritaville. The mountains are to be sure, if angular, a welcome prospective that acknowledges the ranges that are the spine of the state, hardly as austerely patriotic bent of the South Dakota’s sculpted faces–

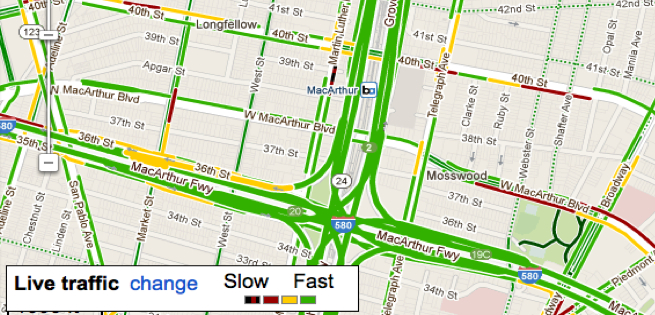

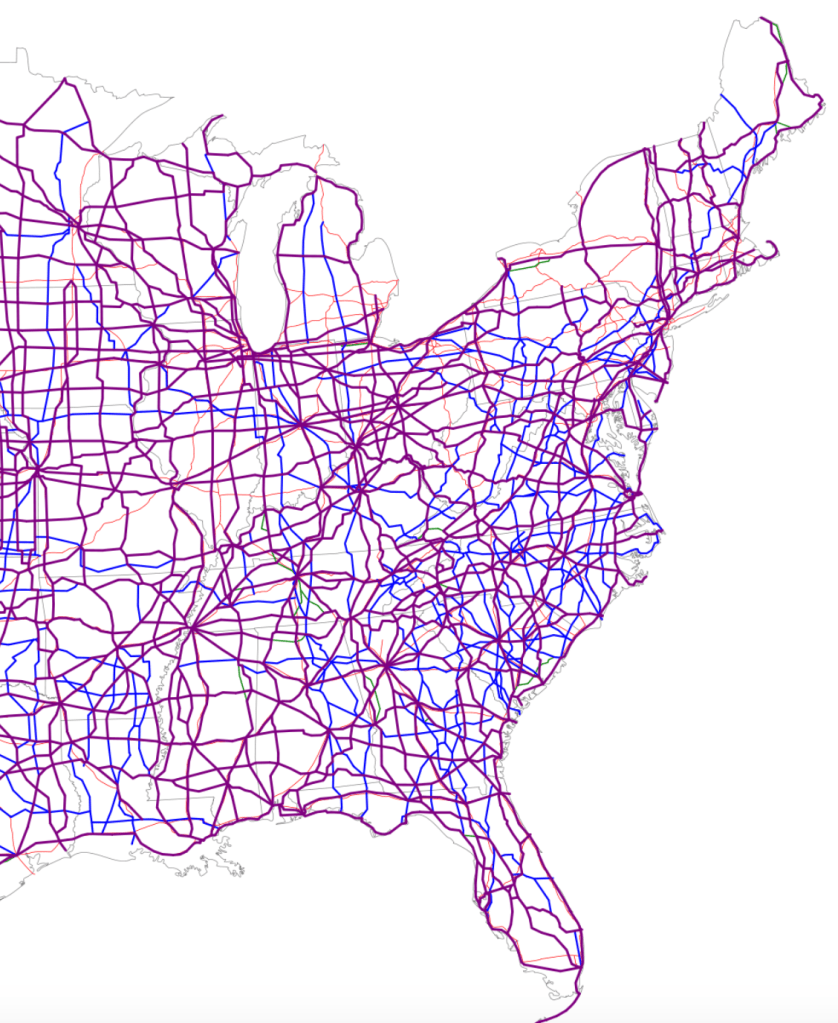

Indeed, the ideal view mediated by the license plate, if not God’s Eye, is about as far from the road as one could get, and intentionally so–a far cry from the plates on trucks that one might see from the midwest, that take the highway map–and geographic image of the state as the center of the USA–that seems unique in reminding one of the highway system left tacit in most license plates!

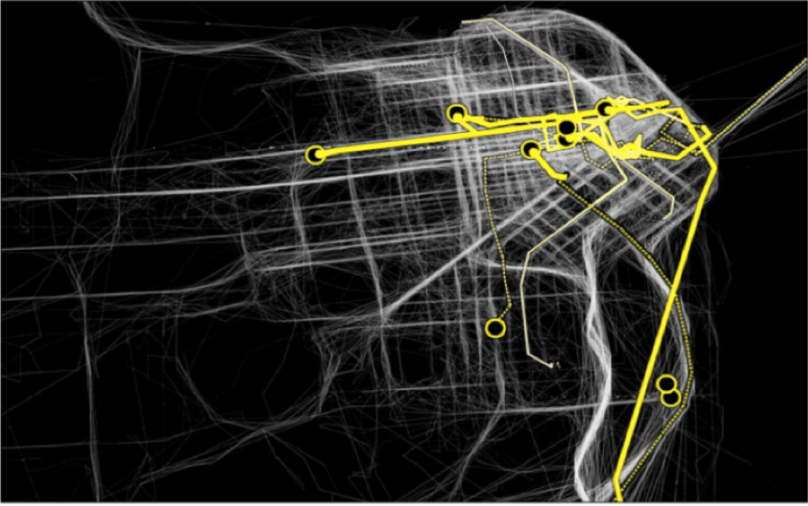

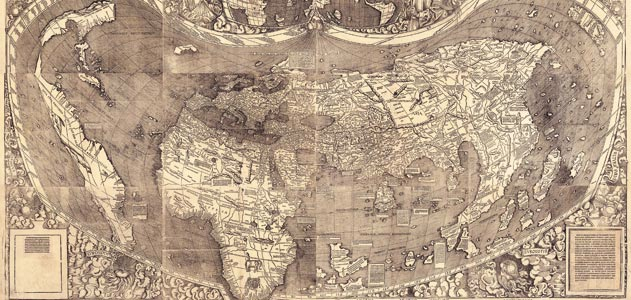

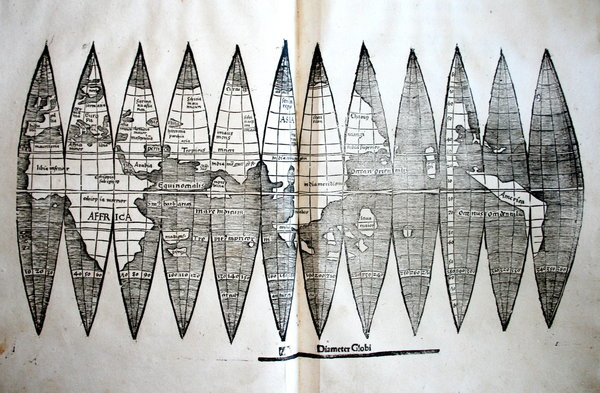

Its design prompts one to remember the central location of Indiana on those unfolded highway maps, in deed, making it an outlier that might very well prove the rule and the thesis of this post. But if the plate was a unashamed symbolization of the power of the midwestern state it maps at the nexus of highways that constitute the nation’s cartographic center, pictorial plates have been adopted in recent years, perhaps encouraged by embossed landscapes, in pictorial detail that almost seek to restore a sense of specificity of place in order to compensate for the placeless spatiality that most motorists experience on most paved highways. Was this due to the death of the paper map, I started to wonder? Or the replacement of physical maps with GPS guidance systems? What of the fate of the maps whose forms used to once define license plates?

Bear me out.

The recognition of place in the frames of plates, increasingly born of qualitative arts, emerged in the 1950s, after all, in reaction to the growth of drives on highways, and the velocity of interstate travel. If cars sped across the landscape, glimpsing roadside scenery without fixed orientation, did the landscapes of license plate promised a sort of counterpoint?

Can this official design–here retaining the vague outline of the form of the state, panhandle to the keys–meet a need for place to compensate for the anomie of the skein of the highway systems and web of interstates that now cover much of the countryside, and indeed constitute almost a space of their own, unmoored from place?

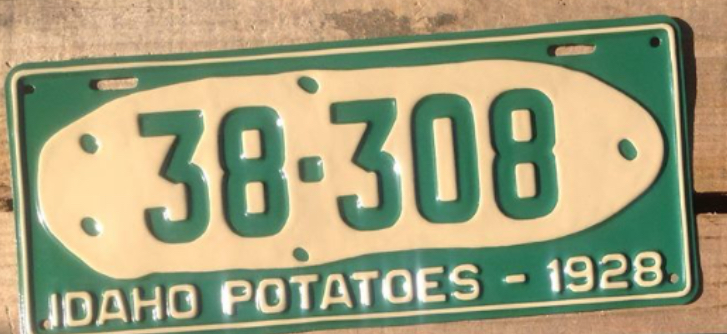

Indeed, the rough condensed history of our roadways often seem to have assumed a sense of replacing the places that they traverse or connect, as corridors of transit may have replaced the dominant sense, for many Americans, of where they are located or what sense of place they occupy in the heterotopia of the road. There is a story that this all began with the potato, the early move of Idaho to rebrand itself as the site of its bumper crop, as if reminding viewers it stood in balance with the open road or the future of technology, as if producing a bumper crop just before the Stock Market crash that led so many to rely on supplementing their meals with potatoes that the first pictorial plate in the United States may well have lost some of its luster.

But the humbler hope of agrarian Idaho’s earthy Secretary of State was not only to attract tourists by a flashy “gold potato” but boost the image of a state beyond an alphanumeric identification or serial design, by a visual symbol of pride that have been claimed to have so radically enlisted artistic license in promoting the state’s self-image to create changed atttitudes to the plate as a space to register not only ownership, but a changed relation to an actual geographic place.

While the image of the potato on a field of green may have been akin to promoting the “new gold” of potatoes to Idaho farmers, to inspire regional settlement, it may be that the interest in promoting interest in the place of the potato would bolster tourism in an increasingly automotive culture, and the Secretary of State must have had some sense in the contrast of the rootedness of the spud in Idaho fields with the cars speeding along its interstate, perhaps headed to the Grand Canyon or Mt. Rushmore, and compel pride of place to make Idaho worth a detour for some time–or even plant one’s roots (or irregularly shaped tubers) for future rewards.

For the first pictorial plate that affirmed the state’s agrarian economy may have been a bit tongue in cheek, a far cry from the open spaces that emerge with a sense of optimistic longing, able to conceal the fact that one is driving in space at high speeds, which if they have included some politicized slogans–as New Hampshire’s commanding assertion, dating back to the Revolutionary War, to “Live Free or Die,” adopted by Gov. Meldrim Thomson as a point of pride to leave his imprint on the sensibility of his state, although the adoption at the height of division around the Vietnam War seemed a summon conservative patriotism, if adoption of the two-fisted motto seemed to manufacture the semblance of a timeless tradition.

The rise of new symbols for states that went beyond a map was suggested in the glorious image of Oregon’s pristine rivers, without a map or even a landscape, in the tones of the incredible fish who return to the state perpetually, traveling along long coastal rivers from the Pacific–the massive Columbia, Snake, Klamath, or Umpquah–by the ghostly rainbow salmon, that suggest the site of wilderness and confluence with the Pacific ocean, to denote the bounteous riches of the state.

As the legends and mottoes of license plates has expanded far beyond that golden spud, to promote a sense of locality that was perhaps less in the earth but similarly evocative of a landscape able to be experienced above the ground. If historian Rick Just argued “license plates became a different thing after that potato,” screen printing and graphic design have allowed the license plate to become a cartographic and pictorial surface of their own, and a sight for the optimistic reinvention of place, as much as a tourist advert: if there was a change in motto as Arizona decided to follow suit with a catch moth, and stamped “Grand Canyon State” on its plates in 1940, as World War II meant that fewer and fewer families visited the national park’s gorgeous trails, and, in the boom of the postwar era, Minnesota beautified itself as a ‘Land of 10,000 Lakes.” The visual surface of the plate has become a site of increasing multiplication of attempts to refashion states as places within the small acreage of the license plate itself, creating idyllic scenes that denoted place, as if in response to the placelessness of being on the road.

The politicization of the design of these most common designators of place on cars, the license plate, is hardly surprising. After all, the rise of the proprietorial sense of designing ones own plates is not a far jump to that of viewing the format of the license plats as if this designation of plate were not forms of public writing. Even without considering the broad notion of what sort of writing this constitutes, the readiness to treat license plate design as if it were an avenue for freedom of speech or a form of expression reveals an identification with self and car to an expressive form and on a semantic plane.

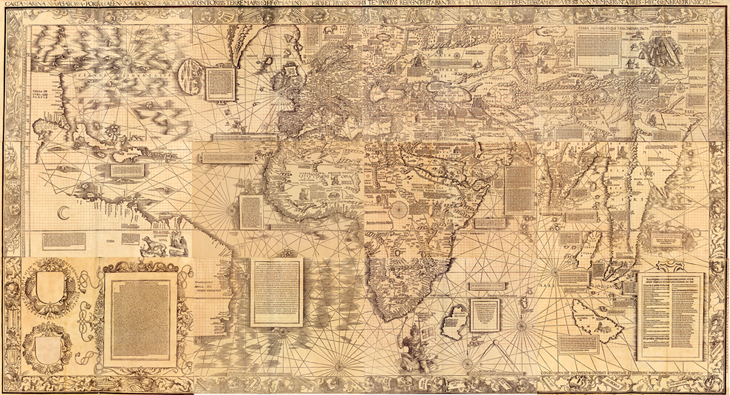

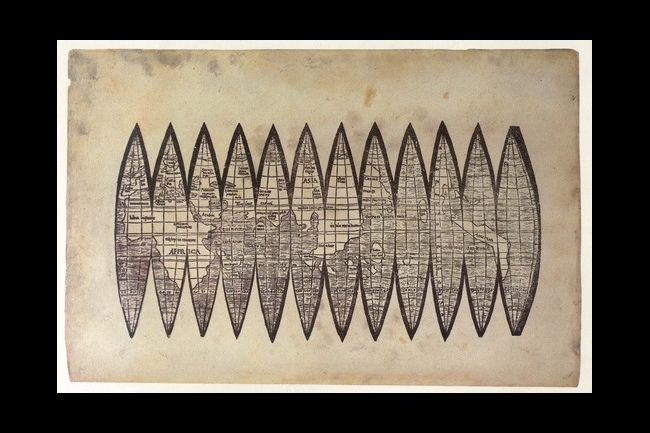

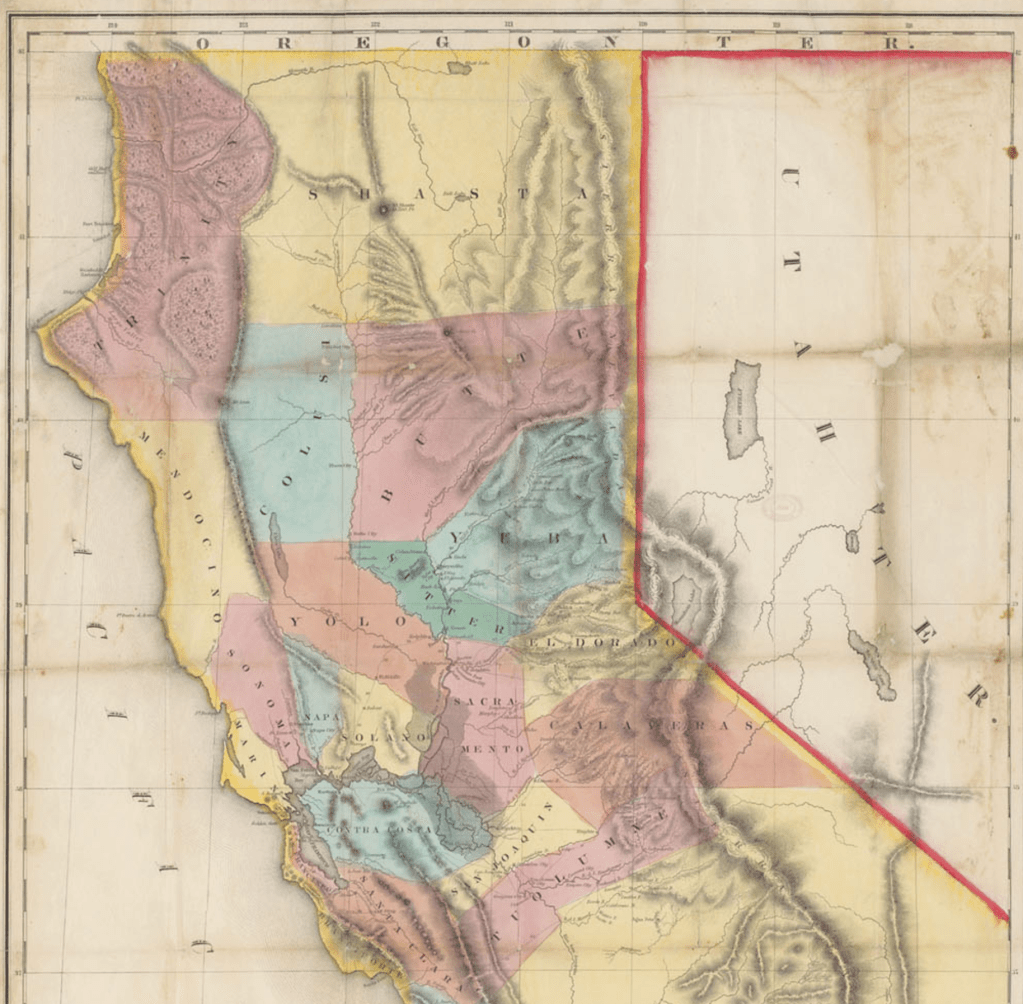

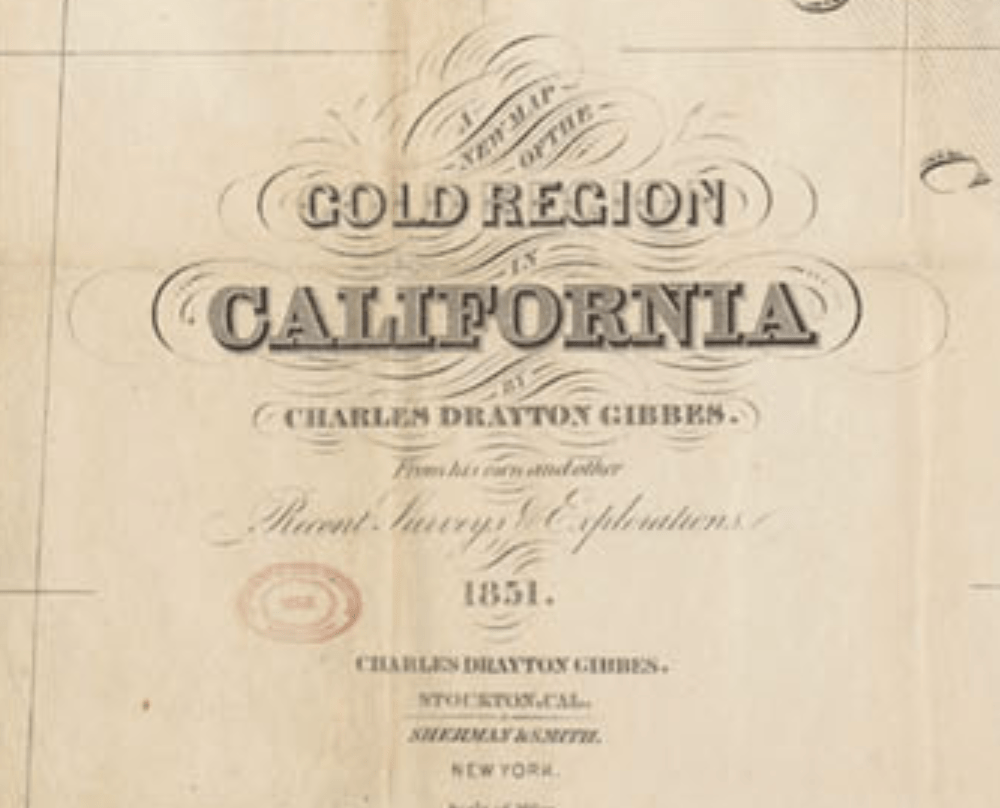

The sorts of legal claims for freedom of speech–or plate–suggests not only an acceptance of the license plate in political discourse, but a pronounced shift not only in the aesthetics but in the use and construction of license plate design from the rudiments of denoting site of registration in the past. If the license plate has only emerged in the past twenty years as a surface of almost pictorial illustration, the purposeful playing with its surface as a sight of design suggests the expansion of graphic design, and understandings of the map as an image of identity. While the gold potato may recall the many maps of the “Gold Regions of California” that were present from 1851 in how Charles Drayton Gibbs promised prospective buyers he had mapped in “Golden California,” using suggesting color choices to suggest where prospectors might do well to look–

the fantastic places of license plates have expanded with both creativity and cartographic guile, showing increasing abandon about their objectivity, and staking greater premium on piquing interest from moving motorists and passersby.

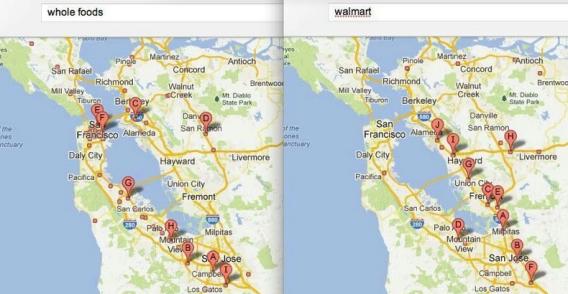

For during the past twenty years, we have come to identify the content of one’s plates as transcends an identificatory tag, expanding its graphic opportunities as an occasion to raise state revenues and provide vanity illustrations of individualization on the highway and driveway at considerable costs. Perhaps it is worth asking how this relates not only to freedom of expression, but to our sense of place. It is perhaps on account of the massive growth of graphic designers and graphic arts, as well as the ease of printing airbrush designs on metallic surfaces, that the license plate, that modest of all surfaces, has recently become something of an advertisement–along the lines of U-Haul moves; the images on license plates have become evocative landscapes that almost embed viewers in their content, depicting a sense of place that seems more alluring than neutrally mapped. Indeed, the growth of new landscape icons on the license plates that are seen on the road seems to have inspired the coterie of graphic designers at Ars Tecnica to assign an award for the “ugliest license plate” to appear, at the start of the new millennium.

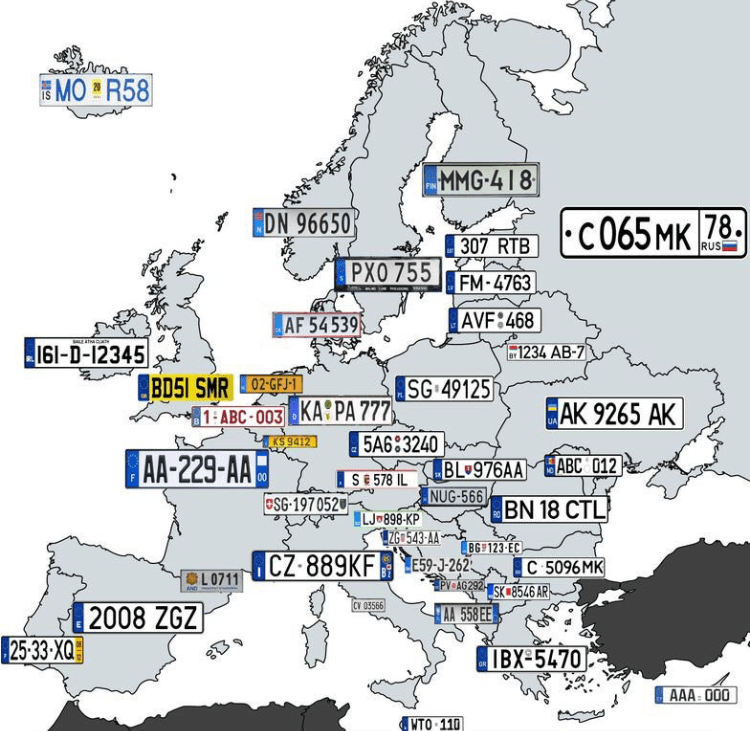

The elevation of the license plate as a site of destination and akin to a tourist advertisement suggested the rise of advertising as much as the pragmatics of automobile registration. The expansion of the world of graphic design to the license plate that suggests a shifting notion to place, as much as of graphic templates in the age of photoshop, but betrays a search for transforming the plate, akin to the car, to a site of identity and meaning, that is deeply tied to the driver’s sense of self, or a convergence of state interests to the desires of drivers, evident in expansive menus of graphic design that DMV’s offer owners of cars, and that offer a gallery on the road, offering a diversity that is sharply American, and seems quite unlike the maps that one might make of European license plates, pre-EU.

Far from seeing the plate as an official signifier, the rise of graphically complex plates moved a stable signifier of location and regional provenance. Beyond being a form of taxonomic classification, or an add-on for vehicle registration, the personalization of plates have brought a search to capture the essence of place of patently nauseating kitsch–

–that summons the struggle for place to still exist in a post-map world, as much as it conjures a sense of place that we might really recognize, as if an affective image that tries to appeal to the state’s residents, by its increasing remove from the geographical map–and far more numinous and faux evocative sense of landscape meant to evoke the magic of place.

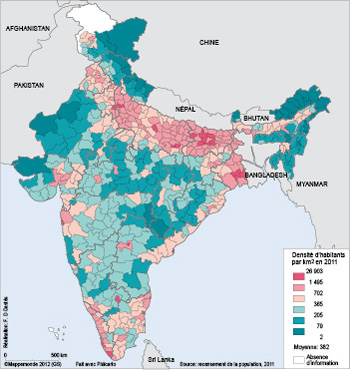

Such a change might well correspond to a sense of the increasing placelessness of a nation that lacks clear edges, and where states have an identity almost invisible save in electoral votes. If the representational unit of the state has declined in national politics, for all practical purposes, there is a sense of reclaiming local identity in the license plate in increasingly immaterial political map.

Indeed, the victory of such airbrushed images of landscapes–instead of maps–seem all too often akin to advertisements for tourist travel, airbrushed imagery, which as much as claiming to evoke a sense of place suggests something akin to perpetual placelessness of an alteration of rural and urbanized landscapes blending into one another, almost suggestive of an appeal for place before the increasing lack of differentiation of the national landscape, even when evoking a map to give stability to a fleeting sense of place.

n

Indeed, despite the radically limited cartographical content of the raised state pictured on the New York State license plate, a considerable effort was invested in affirming the iconic centrality of the state, even it it is a barely recognizable or distinguished blob of paint when raised metal when at close hand.

To be sure, New York license plate design is distinguished by its ability to comprehend a broad geographic unity, and functions as a mapping as an illusion shrinking the geographical distances between, say, Niagara Falls and Manhattan in a somewhat short-lived attempt to spread across the economically and culturally quite diverse state–

–as if to champion the miracle of the transport of water in its hydrological infrastructure, where the water of northern reserves are channeled downhill to fit urban appetites and needs: the parking of two vignettes of quite different scenes, demographics, and even political inclinations, links the upper state and the metropolis of New York City (or Manhattan), by moving from the bucolic scene of Niagara Falls, an abundant cascade of water and iconic from postcard view, to the image of the Empire State Building in the concrete skyline, linking built and natural environments in persuasive ways that the state map may in some ways fail to do so effectively any more, using the old role of vignettes to construct a new affective regional identity–

–that trumps actual geographic continuity, if embedding both in an imagined skyline, itself bridged by the words “New York.” more than reality. The license plate relies on the map, even if only as an atrophied remained, as a hyphen between alphanumeric license numbers, to create this bridge, and remind us of the affective relation to a region!

Although these dramatically reduced maps are but tokens, a visual pause between digits, numbers, or letters, and have lost geographic identifying functions for most states, they affirm a sense of unity. The placement of small, raised maps in northeast states–New York; New Jersey; Connecticut; and, to an extent, but in a different fashion, Pennsylvania–suggests a survival of the cartographical as a remainder of which some states are not ready to let go or consign to the dustbin of history, even in an age of GPS and digitized maps. Not really a visual fetish, but a designator of place, distinguished by an exaggerated appendix of Long Island, the New York image is no doubt the most familiar and recognizable, even if its edges are quite abstractly smoothed so that they provide little resemblance to an actual map, which is reduced to a mere token.

While the map is paired by a similar centrality of New Jersey in license plates in the greater metropolitan area–and in the image of the ‘keystone state’ that is used to punctuate Pennsylvania plates, the diminished centrality of the map in license plates suggests a certain sense of loss, and a sense of bolstering the symbolic currency of the meaning of the old jigsaw puzzle map.

To be sure, there is an ativistic survival of maps migrated into some license plate templates, as if to curry favor among an older audience–that continue to try to reconcile the built horizon of Detroit and the bridge that spans the great lakes with the blue icon of those majestic bodies of water themselves, which, while in fact spanning several states and two nations, provide a symbolic shorthand for the state and its unity to the Upper Peninsula, as well as foregrounding or advertising its spectacular peninsulas–

–as the sun setting over Lake Michigan, in the prospect of “Great Lakes Splendor” shows a sunset through the iconic span of the bridge, foregrounds the landscape’s unity by cool blues lake waters.

The issue may be relatively pronounced. For unlike other states, save Hawaii, and no other non-cosstal states actually bridge bodies of water in their sovereign space. Indeed, if maps provide the most familiar and powerful ways of uniting space in a coherent fashion, the problem of coherence in the “other border state” are profound.

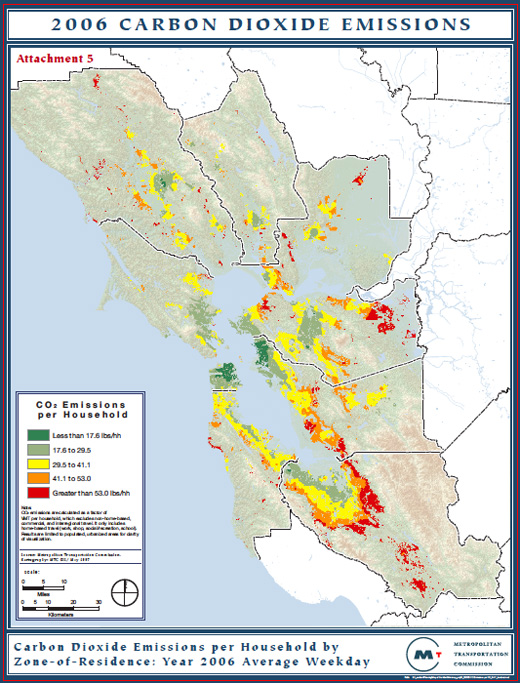

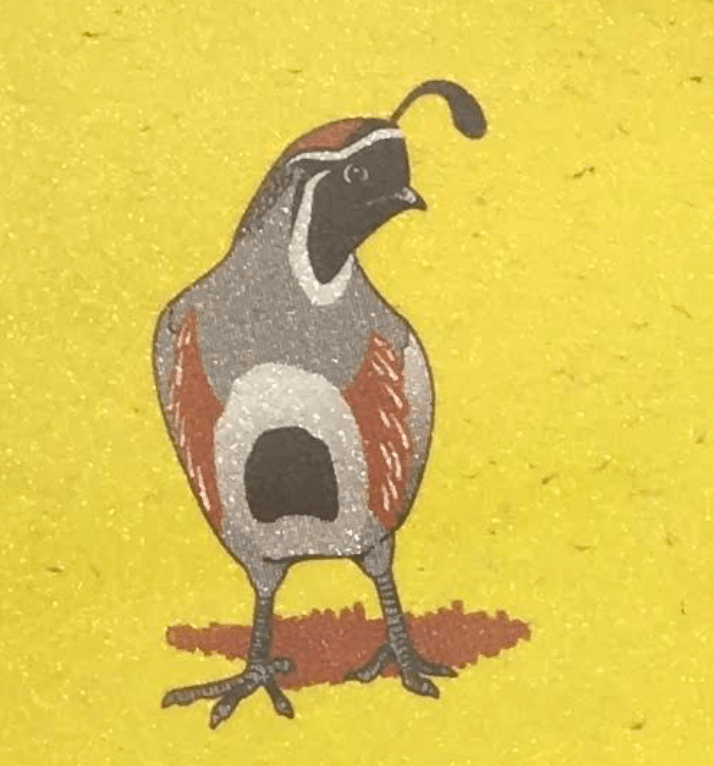

There is a cure pleasure, indeed, in attempts to restore a sense of native habitat, all too rare in the license plates I have studied, by foregrounding the natives quail of New Mexico–an added treat when this motorist discovered it was a feature that was an option at his DMV, and a way, perhaps, to compensate for deep guilt at the change of global atmosphere that the release of carbon and greenhouse gases the driving of the car–even if it is electric–releases while on the road.

–if the inclusion of an actual non-automobile driving person to watch out for on the road seems to be one of the more important injections that would lead the license plates to be seen as a valuable injunction drivers should not lose sight–in this case, quite brilliantly fit within the Rocky Mountains of the Rocky Mountain state.

A strikingly similar generic skyline was adopted not only for Colorado, the Rocky Mountain State, but in grisaille tones, by the state of Montana, less sporting, perhaps but with a broad deep-ground perspective that situated the state on the edge of the mountains, using the greytone minimalism to suggest a broadly atmospheric setting, if with markedly less snow.

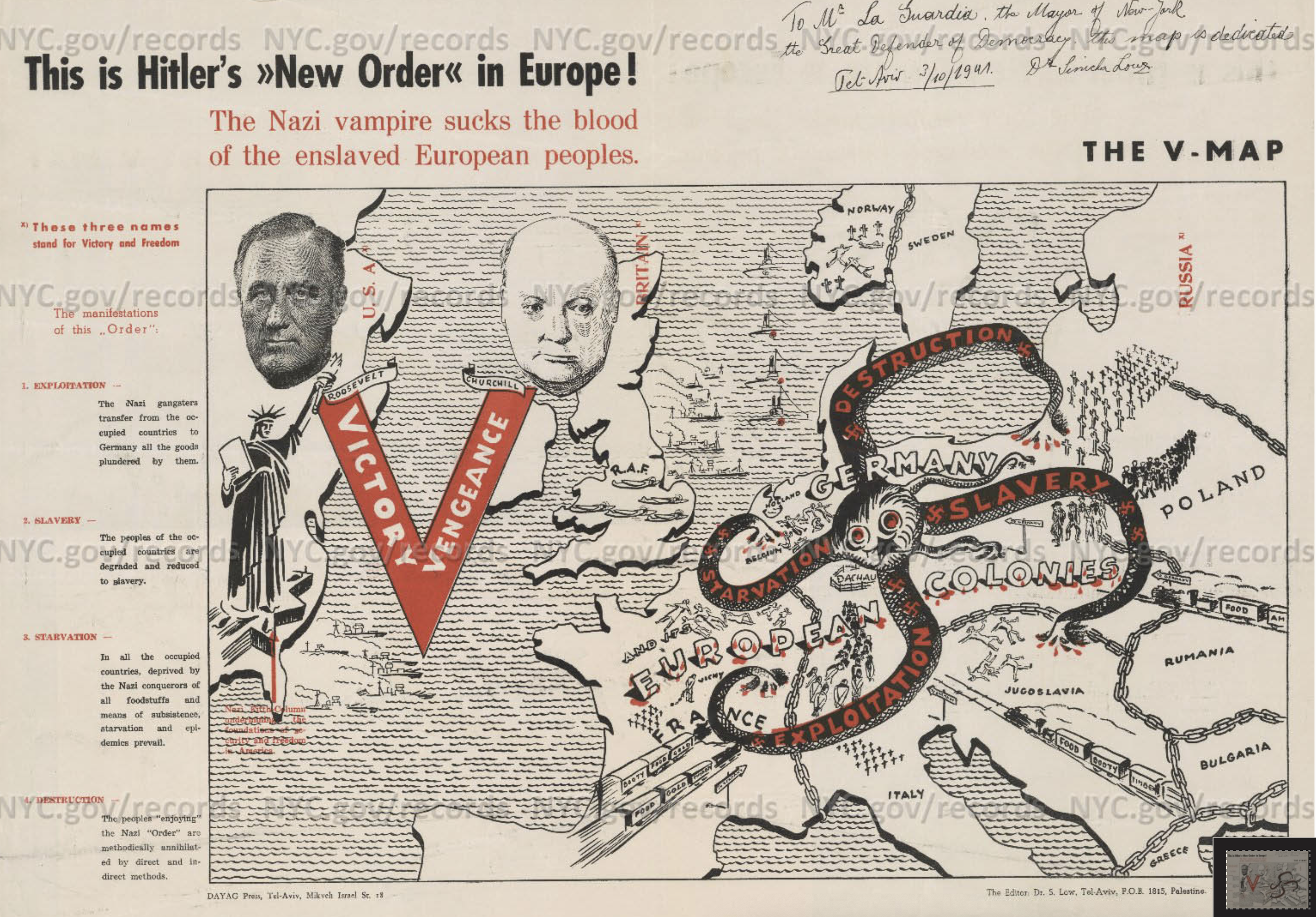

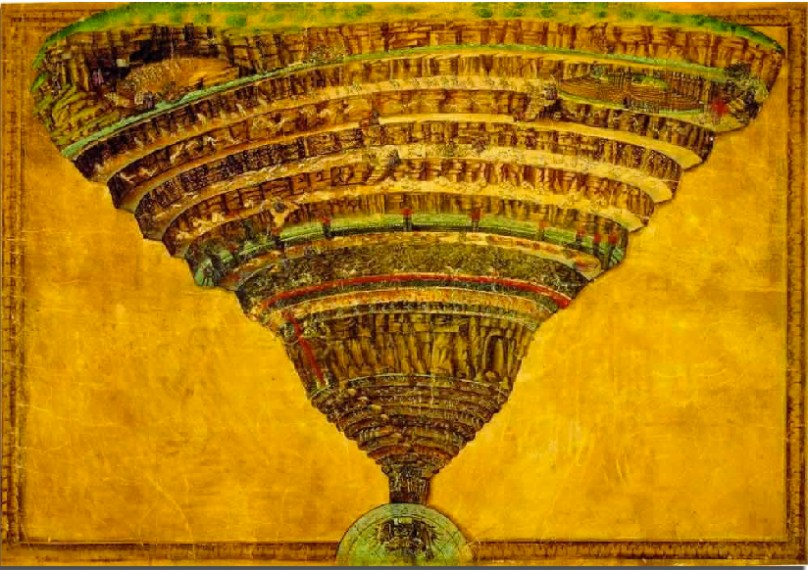

aBefore these maps of spaces of dehumanization and devastation, we are really looking into hellish worlds we had not been able to see before. But even these dots cannot capture the scale of the hellscapes that emerged for the accelerated loss of life within the industrialization of death that proceeded from Heinrich Himmler’s order of 19 July 1942 stated that unleashed mass-killings from bullets, fire, and gas extermination to fullifll the demand that by the end of December 1942, all Jews, gypsied in Greater Germany be killed, leading to an unprecedented intensity of rates of mass-killings almost impossible to map on paper or by a graph, challenging as the spatial dynamics of the three-month long burst of killings is poorly documented–intentionally–and

aBefore these maps of spaces of dehumanization and devastation, we are really looking into hellish worlds we had not been able to see before. But even these dots cannot capture the scale of the hellscapes that emerged for the accelerated loss of life within the industrialization of death that proceeded from Heinrich Himmler’s order of 19 July 1942 stated that unleashed mass-killings from bullets, fire, and gas extermination to fullifll the demand that by the end of December 1942, all Jews, gypsied in Greater Germany be killed, leading to an unprecedented intensity of rates of mass-killings almost impossible to map on paper or by a graph, challenging as the spatial dynamics of the three-month long burst of killings is poorly documented–intentionally–and