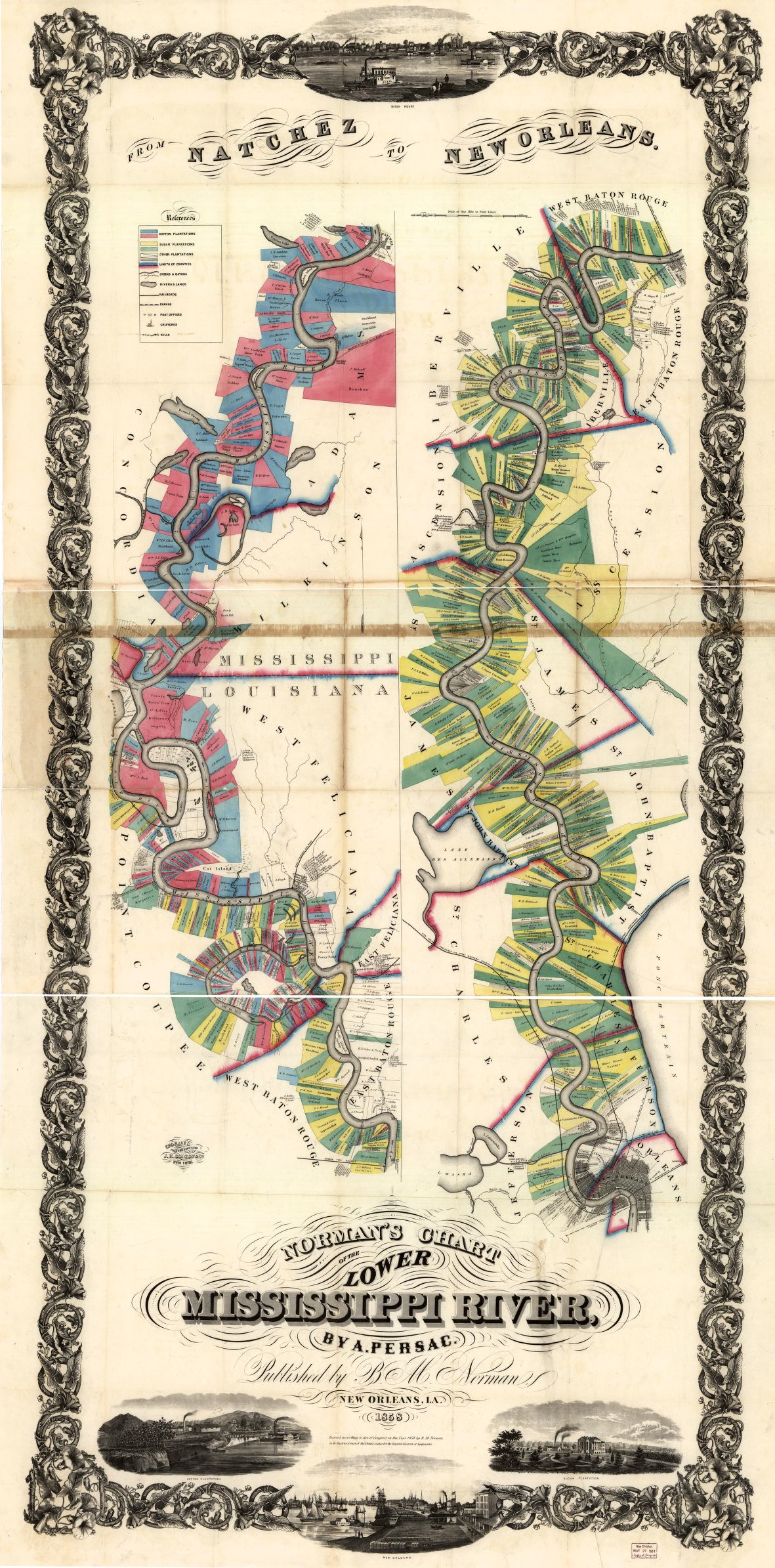

Symbolic maps of the Holy Land are unlike the local maps created for establishing territorial boundary lines or land-ownership that set. But they have come to enshrine shared precedents and common recognized grounds of law, defining property lands of cultivated land. Such maps acquired the status of legal precedents–indeed, they were ways of enshrining rights of possession in the law, even when limited legal grounds existed for territoriality or for dividing rights to areas where no evident natural boundary existed, and were to an extent imitated in these maps of the Holy Land. The influential fourteenth-century jurist Bartolus of Sassoferato, among whose many briefs of Roman civil law one had defended the legal governmental rights of city-states in the area of central Italy, famously appealed to the authority of maps to resolve disputes over river rights and alluvial deposits between towns by maps. Although Bartolus’ influence, considerable before 1800, developed outside of a clear notion of government territoriality, he appealed to maps to resolve ownership boundaries outside of local statutes, in ways to create a common understanding and consensus about the occupation and ownership of a potentially disputed plot of land. The determining tools of cartography afforded the authority for manufacturing the map in ways that provided a precedent for drawing property lines, and bounding a landscape’s expanse which could be regularly provided and widely recognized. This 1689 image of Bartolus’ treatise on the manners of measuring river rights uses a quadrant of Euclidean derivation to transpose a river’s winding serpentine course into geometric fixity, translating his discussion of to seventeenth-century surveying practices.  Lines of jurisdiction are of course still particularly fraught, despite Bartolus’ appeal to the rule of the quadrant, and difficult to transmit, and not only around rights to rivers, some centuries later, but the value of maps in recording an authoritative transcription of rights emerged as a powerful judicial concept in similar quaestio, providing a precedent to which one could appeal as a form of priority. The authority of the map as a form of access to a precedent emerged in a context of reading that shifted from historical terms to juridical terms in an oddly circuitous way, in which the conjuring of territories came to be invested with quasi-legal qualities; indeed, to argue that the map conjures the territory or synthesizes it into existence collapses the complex process of mediation, causation and transmission, in which the map serves in very powerful ways. Sacred maps demarcate a sacred space that collapsed historical time in powerful ways. But once translated into historical terms, such maps materialized cartographical precedents, even if they when more rooted in a cartographical imaginary than in surveying practices or jurisdictional claims of a state. But historical maps of Palestine acquired a sense of authority as precedents in what might be seen as a sort of cartographical promise, as the map came to offer a tangible image to the historical imagination that also suggested a record of historical precedent.

Lines of jurisdiction are of course still particularly fraught, despite Bartolus’ appeal to the rule of the quadrant, and difficult to transmit, and not only around rights to rivers, some centuries later, but the value of maps in recording an authoritative transcription of rights emerged as a powerful judicial concept in similar quaestio, providing a precedent to which one could appeal as a form of priority. The authority of the map as a form of access to a precedent emerged in a context of reading that shifted from historical terms to juridical terms in an oddly circuitous way, in which the conjuring of territories came to be invested with quasi-legal qualities; indeed, to argue that the map conjures the territory or synthesizes it into existence collapses the complex process of mediation, causation and transmission, in which the map serves in very powerful ways. Sacred maps demarcate a sacred space that collapsed historical time in powerful ways. But once translated into historical terms, such maps materialized cartographical precedents, even if they when more rooted in a cartographical imaginary than in surveying practices or jurisdictional claims of a state. But historical maps of Palestine acquired a sense of authority as precedents in what might be seen as a sort of cartographical promise, as the map came to offer a tangible image to the historical imagination that also suggested a record of historical precedent.

For although they were less easily treated as precedents of similar binding force, historical maps increasingly came to stake claim to the inhabitation of the land. And in few cases can the relation between map and territory become more fraught with complications, and more delicate–especially when the same map is also being used to construct a nation, and is so strongly conjured from biblical writings as a way to imagine the existence of a new homeland. The historical maps of Palestine, framed in considerable detail long before the eighteenth century rise of jurisprudence, offered a compelling basis to organize and encourage readers’ familiarity with sacred toponymy and bounds that long anticipated European settlement of the land–and encouraged increasingly complex narratives to be attached to their own reading. The description of the historical borders of ancient land of Canaan encouraged an outpouring of early modern cartographical materials in the first age of widespread cartographical literacy, or familiarity with the authority of the map. The expansive fourteen-sheet wall map of Canaan executed by that industrious seventeenth-century mapper of England‘s territories, John Speed, is lost, but it expanded the 1611 “mappe of Canaan” he designed for the King James Bible–whose design was sufficiently tied to his cartographical competence that he secured a privilege for its reproduction. The map organized narratives about the Holy Land in ways that invested the region with a clearer sense of territorial identity it seems not to have earlier enjoyed. When Speed mapped the Holy Land in the seventeenth century, the map created a model for reading biblical space; William Stackhouse amply provided extensive maps in his 1744 New History of the Bible from the Beginning of the World to the Establishment of Christianity as historical documents of the boundaries dividing Canaan: the map of Canaan in his History afforded a material basis to understand how the Roman census divided inhabitants of the Holy Land, a territorialization of tribal divisions lended concreteness to the occupation of the region by Israelite tribes into discrete regions administered by Roman governors on clearly drawn lines. The national maps that Speed had earlier fabricated provided a precedent for mapping Canaan–not only as the “eye of history,” as the humanistically-educated Jean Bodin and Abraham Ortelius proffered in their maps–but as a form whose boundaries constituted something like a precedent to a modern nation-state. Speed had received a privilege for his “description of Canaan, and bordering countries” in 1610 that took advantage of recently increasing cartographical literacy to extend biblical readership by supplying maps of ‘the Ancient World’, ‘Palestine as Divided among the Tribes of Israel’, ‘Palestine in the Time of Christ’ and ‘The Eastern Mediterranean World in the First Century.’ Such images recast the functions by which maps invited religious meditation in the early printed bibles of Lutherans, by evoking territorial terms that prefigure if not invoke sovereignty. The curate Stackhouse, former grammar school headmaster expanded the authority of engraved maps in Bibles printed from 1733, and expanded in a two-volume edition of 1742-4, “rectifying Mif-Tranflations and reconciling feeming Contradictions, the whole illuftrated with proper Maps and Sculptures.” In it, Stackhouse’ “Map of Canaan, Divided among the 12 Tribes” was a surrogate for the map Revernd Stackhouse surmised with due consideration God provided “to shew Moses the compass of the land.”

The Reverend Stackhouse explained to his readers that, given the difficulty of displaying the land of Canaan from Mount Nebo, “Jews indeed have a notion, that God laid before him a map of the whole country, and shewed him therein how every part was situate; where each valley lay, each mountain, each river ran, and for what remarkable product each part was renowned”–although he expressed doubts that this was the case, since it would dispense with any reason to ascend the mount “since in the lowest plains of Moab, he might have given him a demonstration of this kind every whit as well.” But what Moses saw from the mountain was itself quite comparable a map: although the “visive faculties” required to see Dan and Mt. Lebanon to the north, and the lake of Sodom and Zoar to the south, or the Mediterranean to the west and land of Gilead to the northeast, were “a compass above the stretch of human sight,” scriptures had it that the 120 year old Moses’ eyes “were not dim;” no doubt, Stackhouse surmised, “God strengthened them with a greater vigour than ordinary” that “‘gave his eyes such power of contemplating it, from the beginning to the end, that he saw hills and dales, what was open and what was enclosed, remote or high, at one single view or intuition'” (vol. III, chapter IV, 34-5) The visual presence of the map that Stackhouse imagined bequeathed a sense of concrete entity and identity to the territory that no doubt reflected the authority that printed maps of England had recently assumed, and indeed that the map had assumed as register of national identity. The notion of demarcating a legal territory in biblical times echoed the five maps Speed designed for the King James Bible, and gained a privilege for designing, although based on the earlier efforts of “the learned divine” John More. These maps were commissioned to encourage vernacular biblical readership, but respond to a sense of cartographical literacy unlike earlier maps of Palestine or Canaan. Speed’s maps coincidentally paralleled his project of uniting the parcels of English territory in the 1610-11 Theater of the Empire of Great Britain, creating a composite legible image of national sovereignty across England, Wales, Ireland and Scotland, in ways that abstracted an entity from the land that was earlier difficult to be cartographically imagined. The widespread republication of Speed’s atlases and Theater in the 1670s and 1680s that included maps of “His Majesty’s Dominions Abroad” on its title–and maps of New England, Virginia, Barbadoes, and the Carolinas, broadening the canvass of the nation. Reverend Stackhouse built on this precedent of recording imperial unity by offering a territorial explication of biblical narrative in his New History of the Holy Bible: his “proper maps” were proper since they set a standard for the symbolic mapping of the region that might have been read by Abraham, and offered a basis to understand the distances from Nazareth to Bethlehem as bound by legally binding frontiers, linking the name of each tribe to a region that reflected the Roman imperial administrative divisions drawn across the Holy Land, as much as its cities. In addressing a larger readership of printed bibles, such maps concretized a detailed and palpable relation to the territory.

The translation of the findings of surveys to such widely diffused maps–and the translation of surveyors’ findings from these maps to later maps that won a large readership in sacred texts–deserves to be examined as a subject of cultural history. To argue that the map conjures the territory or synthesizes it into existence collapses a complex process of mediation, causation and transmission, in which the map delineated an imagined “geobody.” And the emergence of “historical” maps of the Holy Land raises questions of how the map only becomes the territory over time. Where the palpability of such images derived from, and how they were deployed for a wide readership across a broad geographically dispersed readership, raises questions of the sort of cartographical literacy that came to be communicated about the Holy Land. The layers of translation from territory to map and back again open something like a chasm of misreading how a map maps to a land. The attempt to restore the bounds of a broader “Greater Israel” beyond the national bounds of the nation–and returned its bounds to the “Promised Land” described in Ezekiel or Genesis 15:18-21–bizarrely transpose a sacred text to the project of the mapping of the nation, current among some more right-wing parties of the current Israeli state. The multiplication of alternative maps expresses a dueling between contesting visions, still needing to be fully mapped, and exchange between an imagined unity and the state’s actual boundaries. As the reality of the state of Israel has grown, the map that informed it, however, takes on new urgency–if only because of the expansion of a mythical-historical perspective on the identity of the same land.

The inclusion of a series of geographically situated Battlefields of the Twelve Tribes in this 1864 map of the same territory lent considerable tangibility to the map of the Holy Land as a detailed historical topography, based on the current surveying of the same landscape. The positioning of the sites of ancient battles against this field of clear elevations, hillocks, rivers, the Dead Sea and other topographic realities created a sense of concreteness that bestowed a sense of strategic encounters in an actual lived terrain–something of a proxy for the hopes for territorial repossession of an actually remote sacred land:

Did such glorious four-color relief maps, published before the Hungarian journalist Theodore Herzl called for the creation and foundation of a Jewish homeland in his 1896 Der Judenstaat, help to conjure the territory? For by 1897, Herzl described the goals of Zionism “to establish a homeland in Palestine [that was] secured under public law,” the idea gained resonance because the map had already concretized a claim to the territory and the “legally assured home in Palestine”–long before the the 1917 Balfour Declaration affirmed “the establishment in Palestine of a national homeland for the Jewish people”–transposed the sacred map into a legal precedent, mapping a mythical historical toponymy onto an actual territory in ways with which we continue to struggle, and to which numerous counter-maps have been articulated at the same time as maps are used to try to narrate the geographic displacements and renaming that occurred–so often in the name of remapping the map to the territory, and re-asserting the complex narrative that was itself generated from the increasingly fraught relation between territory and map. The concrete detail of the maps realized the imaginary existence of the region with a concreteness that provided a recognized and recognizable image of lands settled by the Twelve Tribes by 1900 as if it were their property.

And, to jump wildly–and fairly irresponsibly, it must be admitted–across time, after 1948, the negotiation of these sites of settlement and creation of places of habitation was considerably more complex to negotiate, as this recent map of Israel’s relation to the occupied territories reveals, a process of negotiation building from and negotiating the attempt to integrate Gaza or the West Bank in an earlier notion of a “Greater Israel.” More pressingly and compellingly, than this cartographical fantasy is the manner that the image of land defined the bounds of the land’s inhabitants by 2007.

The “other” side of the historical story is presented in this 2012 map of the scope of the declining expanse that was bounded in the Palestinian state from virtually the same date–1897–up until the present, a map that seeks to conjure, if it obscures the human cost of displacement of some 5 million Palestinian refugees from the 1948 and 1967 wars and their descendants, now living in Jordan, Libya, and Syria, as well as the West Bank, at a moment commemorated on May 15 as the Nakba Day [يوم الن], or the Day of Catastrophe.

The map is striking for how it reveals a counter-example to the above fantasy of occupation–paralleled a renaming of the land, and a government committee dedicated to the erasure of some thousands of Arab place names, from cities to hills, valleys and springs, was delegated with the task of creating Hebrew names as when David Ben-Gurion affirmed “We are obliged to remove the Arabic names for reasons of state,” dedicating the nation to the project of determining place-names in the Negev, or southern half of Israel. For a more expansive version of this post, please click here.