“A man in the city,” wrote American novelist William Gass, “has no natural thing by which to measure himself.” Self-measurement may be increasingly difficult in an age of global warming. We are with less of a rudder than in the past. But we realize the need for a preserving a close relation to nature, and indeed doing so for biophilic ends. At the time Gass wrote, in the middle of the past century, he disdained the built environment of east coast cities with the wry eye of a midwesterner, even before urban sprawl. The United States was still–as it is now–distinguished by the highest per capita urban areas of any industrialized nation. And the increased overpaying across the west, and bloating of cities that lack edges with wildlife, and indeed only spread into urban walls, means the hope of ‘fronting’ nature, or of imagining a living edge of the end of the city, seems as unknown and as foreign to many urban areas than it has ever been in human history. Even in the most densely populated of American cities, where parks have been built to preserve natural preserves of habitat and recognizable sites of ‘access to nature’ in an increasingly paved world of increasingly hard edges, the concerted belief in the possibility of fostering ‘natural preserves’ in urban ecosystems has endured–

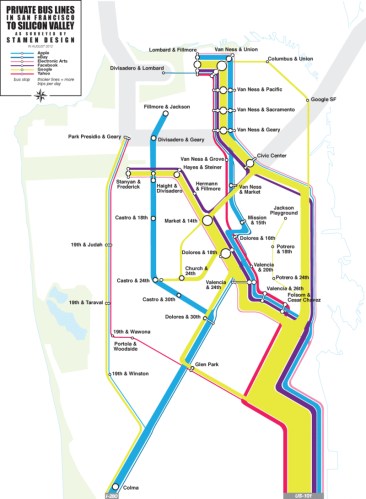

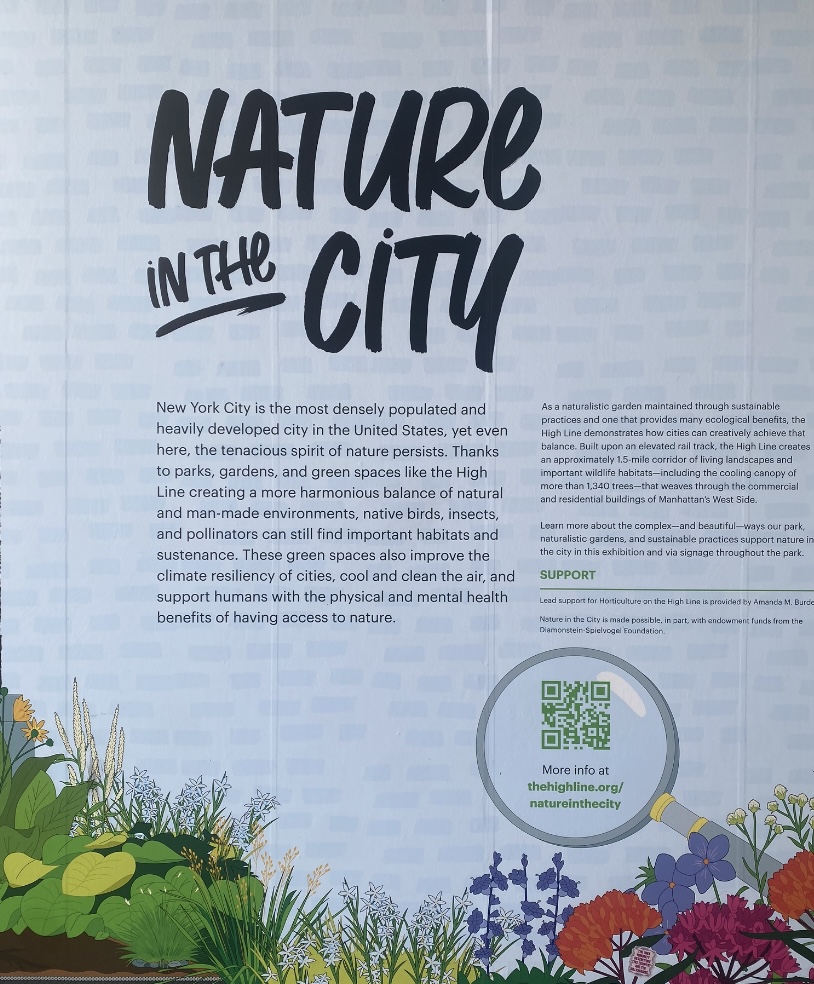

Nature in the City/The High Line, New York City

–promising the preserve of ‘a harmonious balance of natural and man-made environments,’ however distant such a balance seems in an already densely overbuilt environment. But preserving of such contact with reduced wilds provide a sense of hope and indeed a space we might confront where, with Thoreau, to preserve the wild as a site for our rebirth. Whilehopes for fostering ‘native’ species of birds, insects, and pollinators is deeply ethical, the hopes of preserving nature in the city, one worries, has arrived rather late in the game, and after the nickel has dropped. But it is no less urgent, as a process and project for inviting us to remap how our cities are both built and lived–even as the remove of a cabin in the woods that Walden helped perpetuate and foster is receding in the present more than at any time in memory.

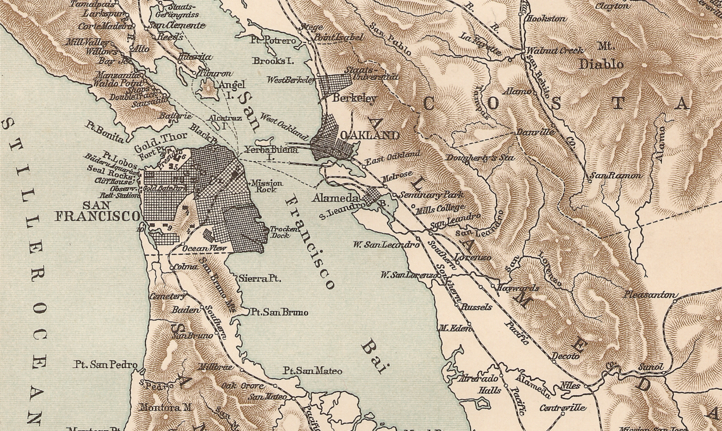

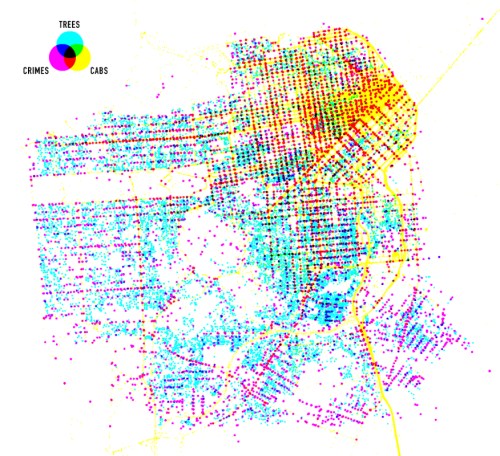

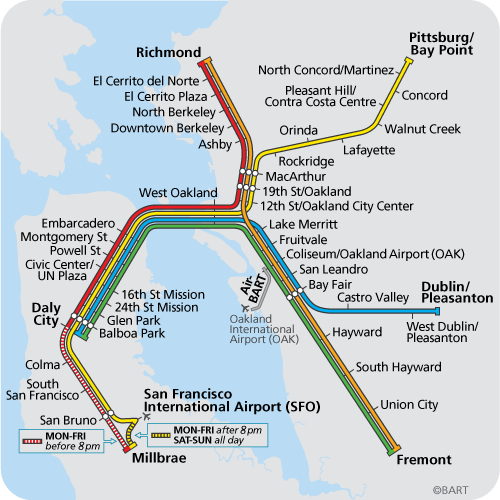

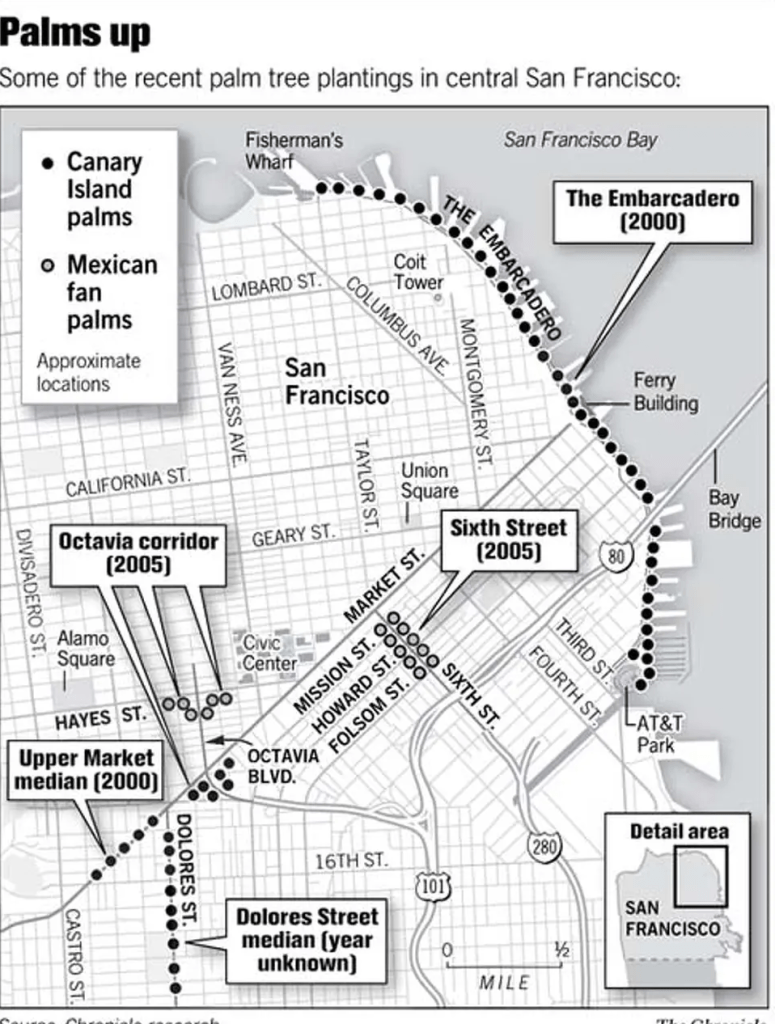

The dangers of urban sprawl in northern California have created a crisis in diminished habitat, and left little space for preservation of the wild, many seek to protect more areas of livable space by securing environments fast-disappearing across the state. And while one of the biggest efforts of San Francisco was to try replacing the concrete streets of the city with strings of fast-growing Mexican fantail palms, in hopes to create a stereotypic landscape of southern California that have filled the national consciousness in the 1920s and 1930s, spending an unprecedented $1.9 million on boosting the beautification of San Francisco after the 1989 earthquake Brough a drop in tourism–in a little noted aftermath–by working to plant palms along the Embarcadero bay and major urban thoroughfares to correct an unwanted drop in tourism to the city–

Palms Planted in Downtown San Francisco since 1989/SF GATE

–the dialectic between needed greenspace and environmental niches of vital habitat that create pressing questions beyond urban beautification, but get at deep problems of urban livability.

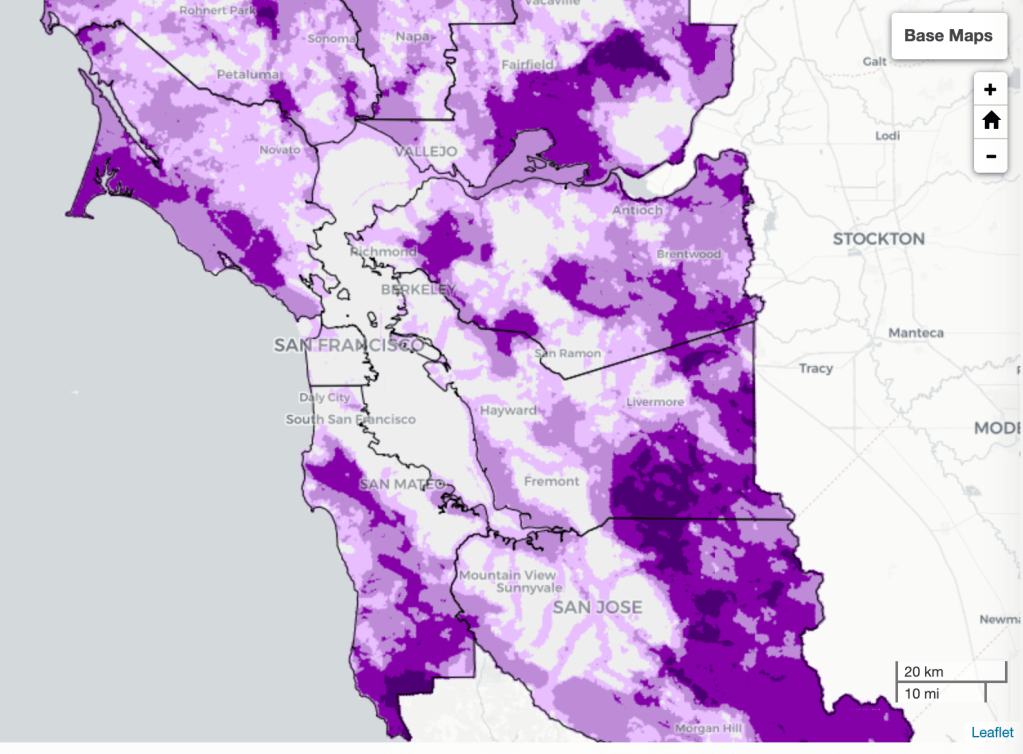

But the need to map our relation to nature has never been more at a premium, and we try to map scores of livability of urban environments in hopes to try to find a connection to nature that is increasingly severed. San Francisco possesses one of the largest municipally managed parks in the nation–over 127 acres–with the slightly larger Park Presidio, a reclaimed military base now a national park. The interplay of nature in the city lies far beyond its parks, but measuring one’s relation to nature are at a premium as the Bay Area is increasingly thought of as far to overbuilt than in the past. If the presence of nature in the city is more elusive, it is more urgently in need of preservation for its residents, and the achievement of the recent non-profit Nature in the City demands to be celebrated as a significant mapping event.

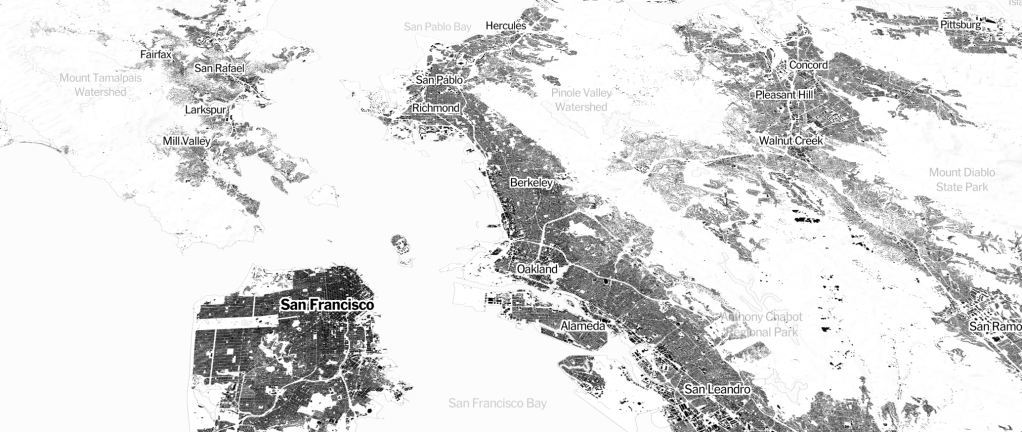

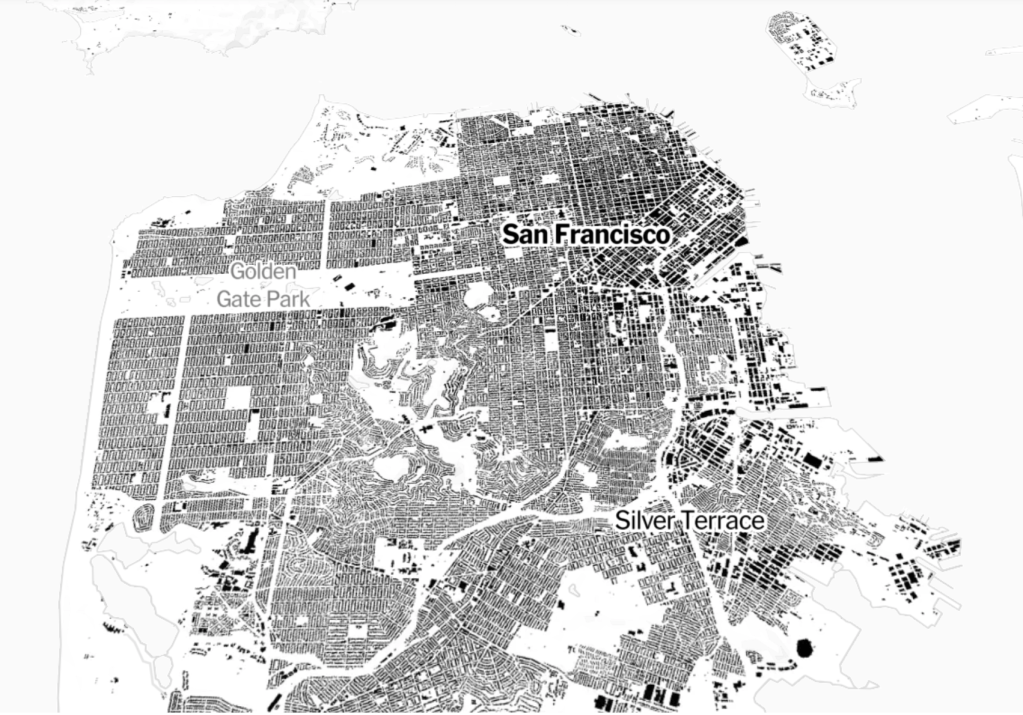

The region around San Francisco is to somewhat unique in offering views of the urbanized downtown from many vantage points and prospects that situate it in nature, against the shores of the Bay or mountains of the peninsula and more rural areas like Marin, as its development offers a test case in the intensification of urbanism and overbuilding increasingly fragmenting wildlife habitat. There is a danger endemic to satellite maps of foregrounding the structures of the built world, rather than habitat, that suggests a cartographic remove of vertiginous danger:, curtailing cognitive interaction with space, as in the machine-read maps of building footprints, “Every Building in the United States,” situating Bay Area buildings as archeological ruins of a Baedecker to a future San Francisco, outside the topographic situation of built space in an area imagined as embedded in natural surroundings. But the absence of life in this overbuilt Bay Area, which maps each building by black, irrespective of height or foundation, recording an anthropogenic legacy via an analysis of satellite imagery converted by Microsoft engineers to a nation-wide dataset, rather than road maps to enable everyone to boost their built built environment as if Robert Moses promoting built space.

But the building outlines of these maps chart the fragmentation of habitat in what was once a site of wildlife. The map poses problems of defining the “wild”–beyond the tropical cherry-headed conures who have escaped from captivity to be celebrated “wild parrots of Telegraph Hill.” The parakeets that fact span the city from the Ferry Building to Brisbane gained local dominance as flocks of urban parrots nesting in the city from 1911, but recent recognition as the city’s “official animal” poses questions of their designation as wild, despite the seemingly distinctive dialect of their animated cries in the evening in urban parks. San Francisco’s feral parrots were designated as “wild” in the 2005 film by self-designated local expert in parrots, Mark Bittner. Since then, many have naturalized the communities of red-masked parakeets in urban ecosystems to which they are not native in California–not only in San Francisco but Menlo Park, Palo Alto and Sunnyvale–and since 1997 in San Diego, reflecting the massive importation of exotic birds since the 1980s: the feral population of neotropical birds gained a toehold in coastal environments since upwards of 26,000 parakeets were imported to United States from 1980-1985 as exotic pets. The feral ancestors of escaped pets colonized anthropogenic habitats’ open arboreal canopies, colonizing habitat abroad by a species nearly endangered in Ecuador and northwestern Peru, whose local pet trade combined with habitat loss, in a paradox of globalization, to send parkeets from tropical to urban habitats.

Prominently audible and visible at sunrise and in the evening, the growth of invasive populations in several city parks have encouraged designating the progeny of imported exotic pets as local wildlife attractions. But this designation begs the relation between nature and urban environment: as relatively recent arrivals, the non-indigenous feral cherry-headed conures are local icons, rather Han seen as invasive, despite their remove from the regional ecosystem, living off flowering trees they adopted as roosts from Coit Tower and Upper Fort Mason from February to October, but native to deciduous forests and jungles in southeastern Ecuador and northern Peru, if often migrating to suburban forests after having escaped captivity, if long popular caged birds introduced in Spain, The colorful local presence of over three hundred roosting in the Bay Area encouraged sympathies as charismatic species, but the parasitic presence of birds escaped from pet shops or released by past owners may mask the actual vibrancy of habitat of the dynamic region in which the parrots can inserted themselves as urban interlopers, winning the protection of many local residents seeking to nurture the exotic birds as colorful splashes in an increasingly overbuilt space.

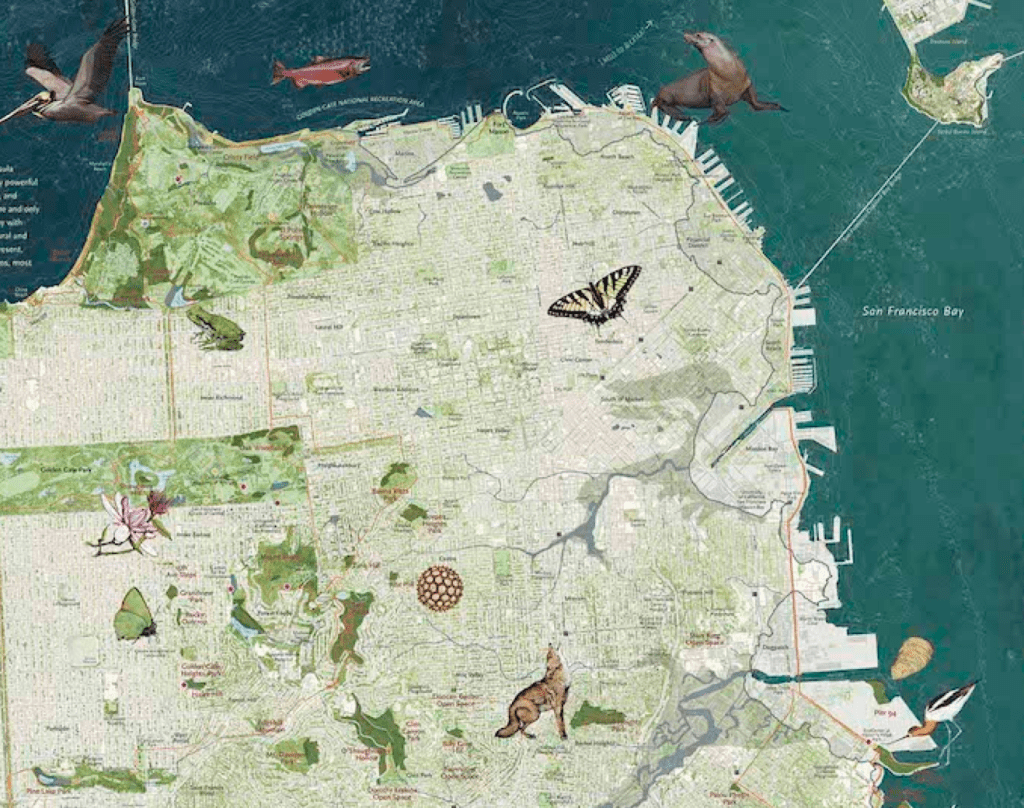

The recent map of urban habitats of the enterprising non-profit Nature in the City is dedicated to the conservation of a new attitude toward urban space, using mapping technologies and artistic practice. It seeks to orient readers to the charismatic species that occupy the city’s greenspace. If the heroic couplets of Vladimir Nabokov’s murder mystery, Pale Fire, staked a mystery of modernity channeling “the shadow of the waxwing slain/By the false azure in the windowpane,” the reflective surfaces of urban buildings create the illusion of open skies even as they interrupt the open spaces of nature on whose reflection the noble bird is a victim of apparent suicide. That bird, an American term for the bird used in the royal crest of a fictional kingdom of “Nova Zembla,” derived from an island called Novaya Zemlya, or “New World,” an archipelago in the arctic in the Barents Sea, was mourned by the emigré author in exile, as the double of Nabokov himself. Can we use datasets to devise a more humane account of the shrinking greenspace habitat, seemingly soon to disappear not only in America, but in its expanding urban regions?

If the first tallies of birds in North America began in December, 1900, instigated by the curator of birds at New York’s Museum of Natural History, the census came to offer a basis for the first scientific count of birds in Canada, the United States, Latin America, the Caribbean and Pacific Islands. The recent iteration has totaled an avian brood of 40 million, of 2,380 species, contracting in size after losing some three billion birds since 1970 in North America. If the count postdated fears Rachel Carson voiced in Silent Spring, it also stimulated the concern. Some visitors to New York may smirk at designated”habitat restoration” in Central Park, but the park’s meandering paths offer humans an exposure to birdsong of sparrows and jays absent from most built space in the urban grid. Do we not need a better maps of relations to nature, in an era of overbuilding where most maps leave us purblind to an anthropocentric record of anthropogenic change?

The ever- increasing of habitat fragmentation poses, with invasive species, and anthropogenic toxins, environmental challenges that make it ethically incumbent for urbanists to foster viable habitat in the expansive urbanized regions of North America. For habitat is compromised by laissez faire building, ifunregulated pesticides on avian life that led Carson to be so concerned for the birds inhabiting orchards whose springtime voices were threatened to be silenced have diminished years ago. The importance of strengthening the habitat of birds, mammals, fish, and insects may make them more resilient, and the hope to “green” our increasingly over-paved urban spaces offers and important response to the increased absence of greenspace accessible to most Americans. The lack of access to the wild, or wilderness, may have led locals seeking contact to nature to devote such misplaced attention to feral parrots, seeking a sense of the wild that the city lacks.

hTis is not only a question of improving urban environment for city dwellers. The compelling notion, recently voiced on WaPo’s Climate Lab, of imagining American cities as ongoing science experiments to provide and afford access to natural habitat, as much as lived communities of human animals alone, is powerful. If the city of New York has lead Central Park Conservancy to promote preservation of its 843-acres as a “backyard of the city” for all residents, in need of habitat restoration, many links that have longed tied the San Francisco Bay Area to surrounding ocean and inland ecosystem offer broad possibilities for mapping to remediate habitat across its built space.

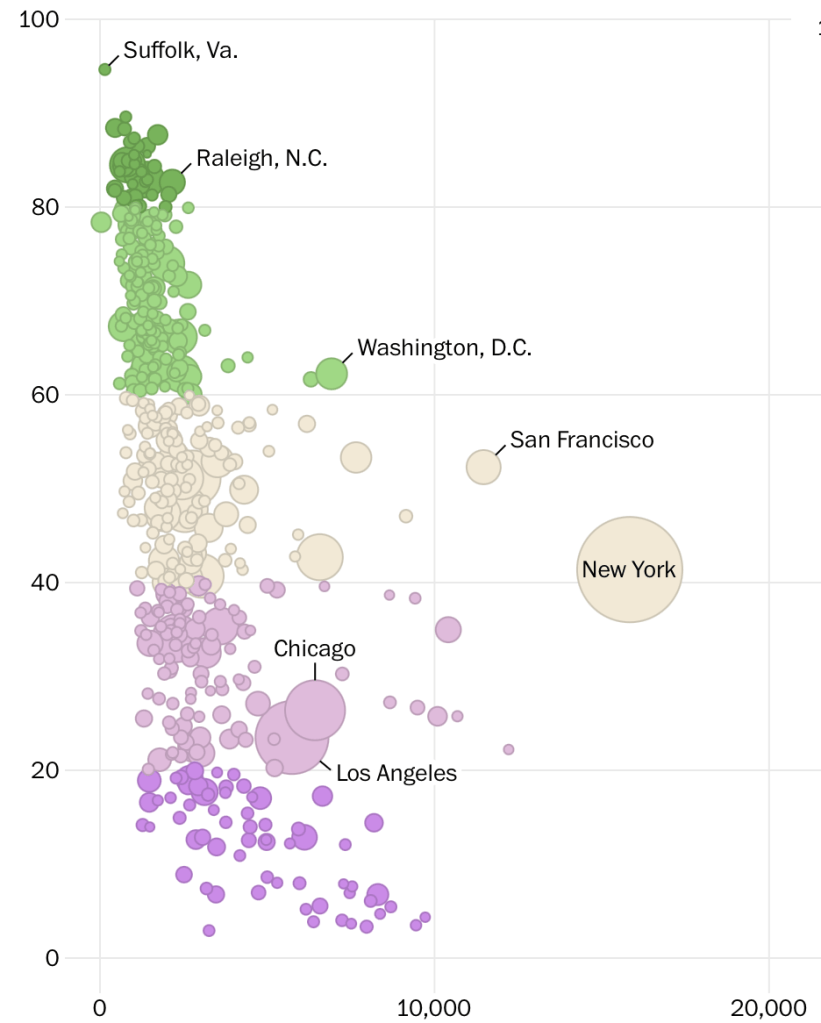

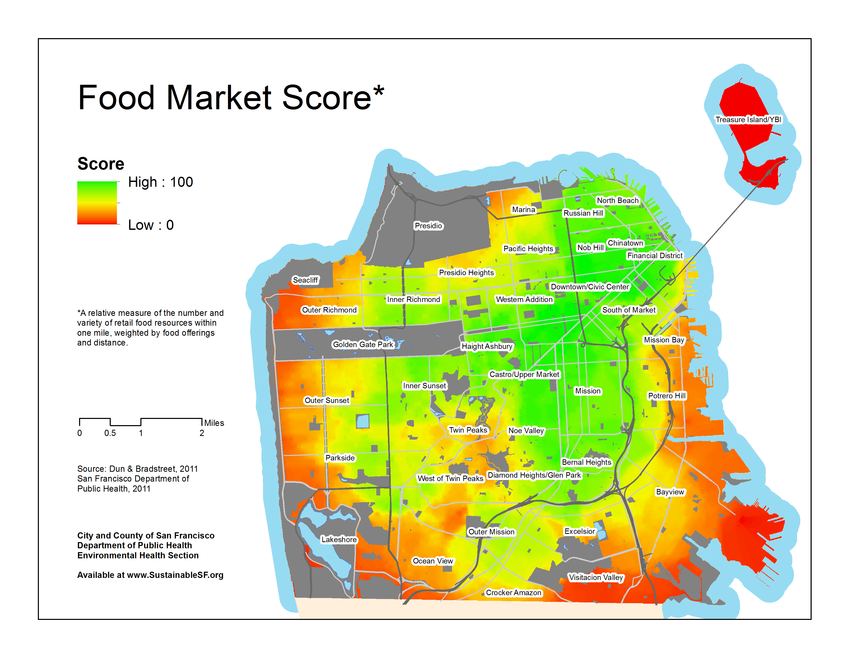

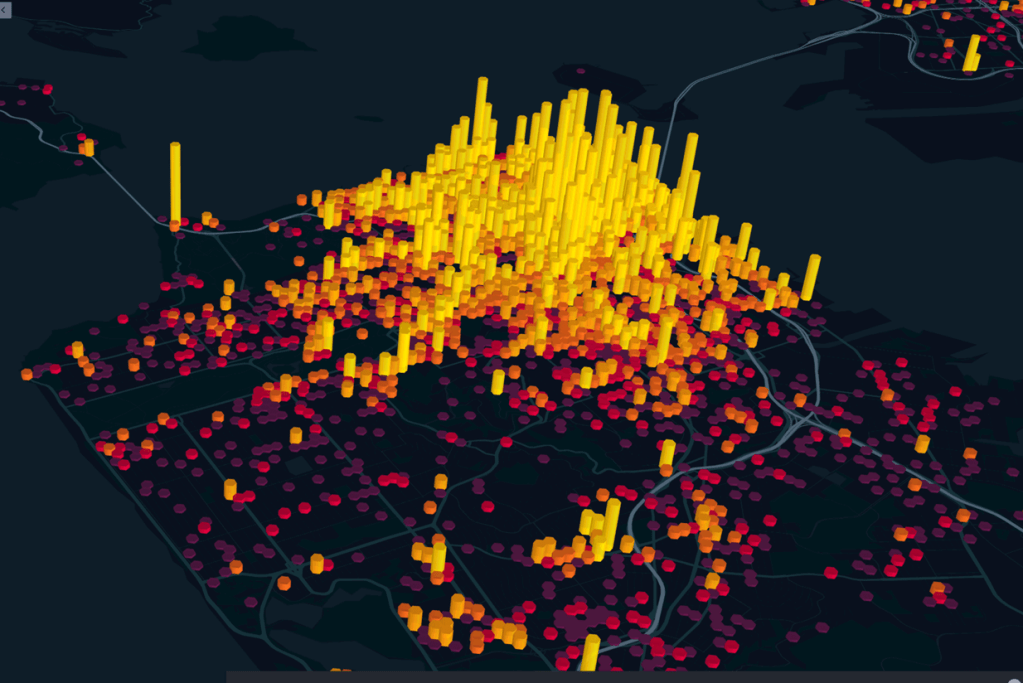

It is based on using the big data of new datasets as metrics to map urban space as offering space that might double as resilient habitat in an age we are threatened by habitat loss and invasive species. Rather than mapping demography or housing density of human residents, interest has grown in measuring healthy tree canopy, access to parks, and diverse plant and animal life in concrete terms, as much as in abstract metrics, to diagnose the health of our urban surroundings in the United States. If much attention has focussed on city-dwellers access to open space, parks, and living ecosystems by which we are increasingly apprehensive of being walled off. As nearly ninety percent of Americans live in cities, nearly ten percent more than when Joni Mitchell the uneven economic exchange by which “we’d paved Paradise” for the sake of putting up a parking lot, the pressing questions of public health, salubrity, and mental wellness led NatureQuant to score zip codes in America by plotting their population density against tabulated “nature scores” of a Zillow-esque exercise of urban real estate, reassessing the “value” of living in urban spaces by an index.

NatureQuant’s Metric Analysis of the Relative Healthiness of Cities (NatureScore) against Population

The quantifying of a city’s healthiness from an anthropocentric point of view may, however, miss the point. For the perils that are faced by many species in an increasingly overpaid world mean that we would do well to attend not only to the healthiness of urban spaces for humans, but the mitigation of the effective fragmentation of natural environments and spaces that the massive if not hypertrophic growth of urban environments in the United States. While much of the Bay Area is now classified as protected habitat, especially along its shoreline and ocean coast, the expanding urbanized agglomerations of “urban regions” in San Francisco, as well as other cities, have made it less of a “green” space than it once was, and make it hard to map the livability of the city habitat it offers–it is suspiciously nearer New York, increasingly, than Washington, D.C.

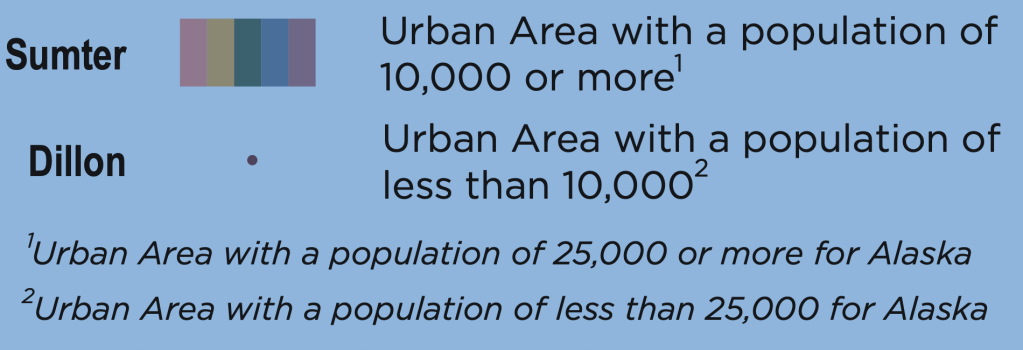

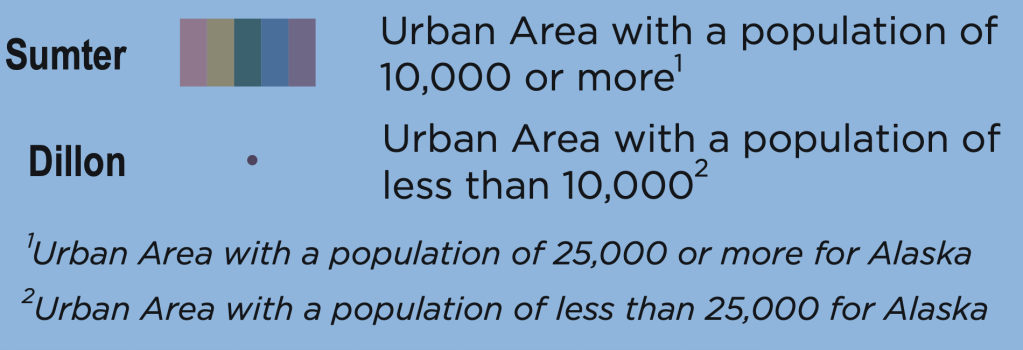

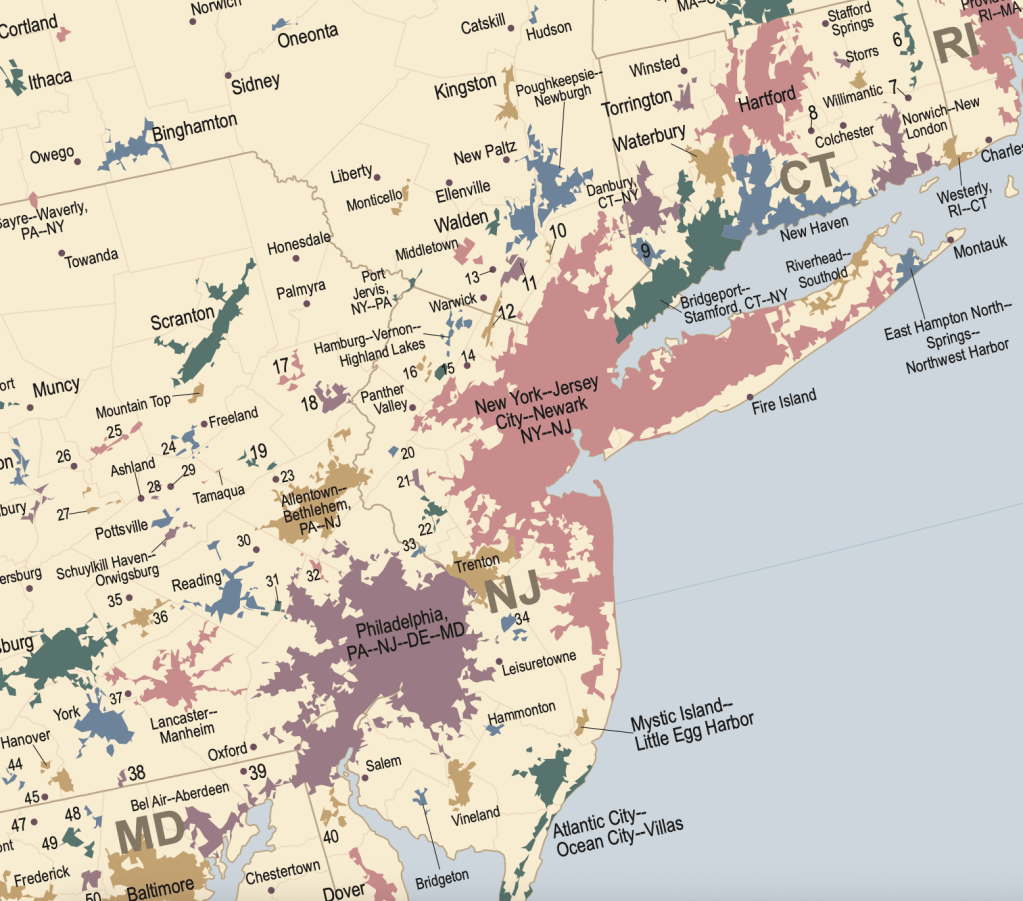

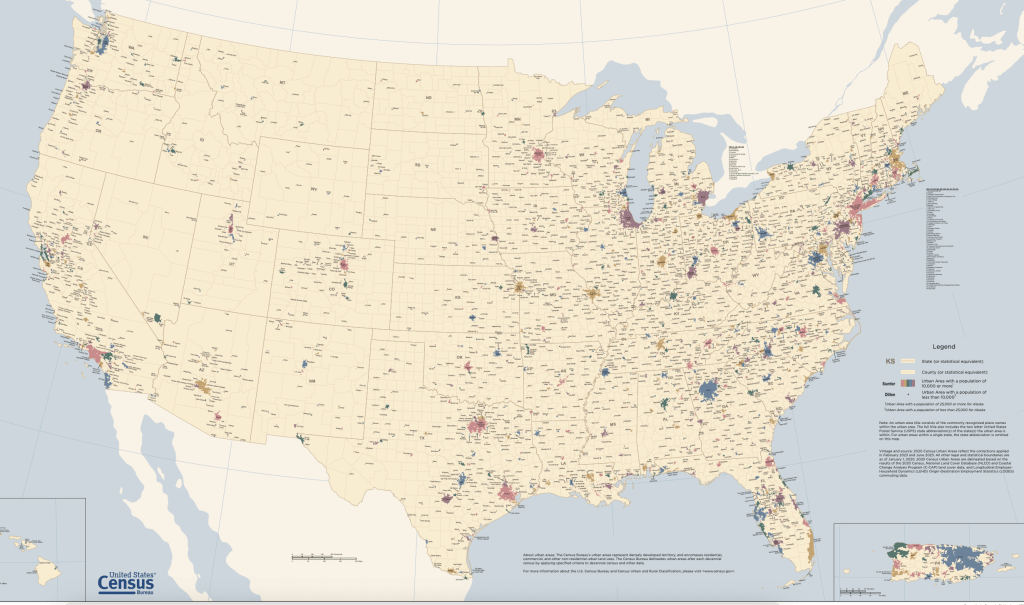

The growth of megacities and expansive urban agglomerations are not only not good for us, but these new urbanized regions, form the BosWash area spanning much of the eastern seaboard to the metro area of New York City, the largest metro area in the United States, the highway-linked expanse of Los Angeles, Anaheim, and Long Beach, or the smaller of the upwards of 2,600 “urban areas” of housing density as much as agglomerations were identified in the 2020 U.S. Census to denote the increased density in which we live. These larger urban areas pose questions for wildlife, or for the existence of habitat–as much as wildland–and questions of maintaining habitat in an era of increasing overpaving. The miasmatic urban areas spread on the eastern seaboard states.of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland are a major fragmentation to habitat–

Urban Areas in United States/2020 US Census

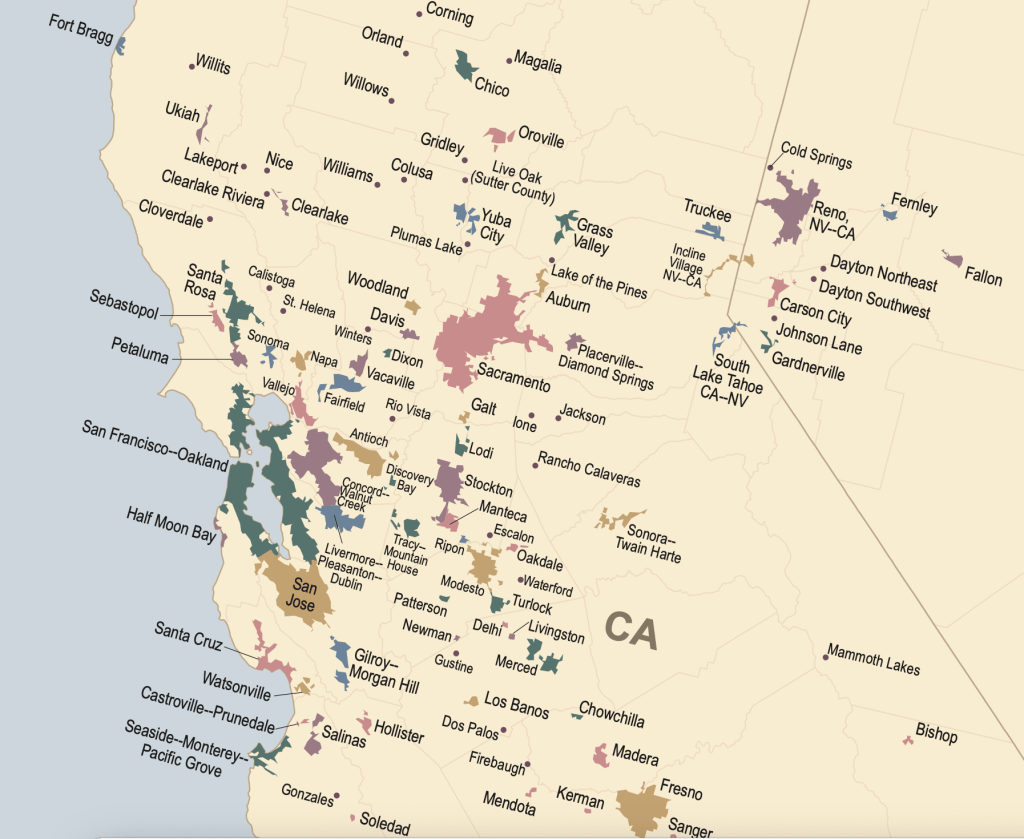

–echoed in the even greater shift in the Bay Area and nearby localities of a density of populations greater than 10,000 that have increasingly impacted the ecologies and ecological habitat of the region that have interrupted the coastal areas, wetlands, and tidal zones that ring the Bay, itself increasingly surrounded or hemmed in by urban agglomerations that endanger habitat, as entities now known as Urban Areas, not cities, merge and slide into one another, paved tracts of urbanized land with no clear borders or bounds, as needs for interconnection trumps corridors of wildlife.

Urban Areas per 2020 U.S. Census of Areas of 10,000 or More

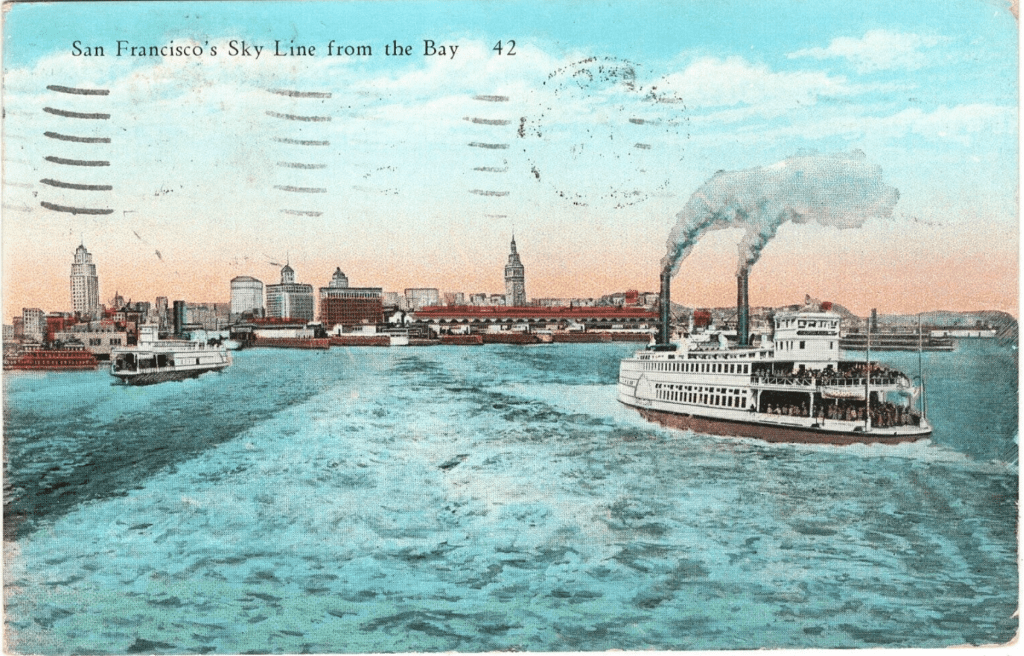

In the years leading up to the 2020 Census, the region was pervaded by deep anxiety, indeed, about the restriction of corridors for habitat and wildlife that have long distinguished the region, a contraction of habitat corridors that have become increasingly sensitive to many residents, in need of making their own reaction to nature, and indeed to map proactively to preserve the wildlife corridors. If wildlife corridors and shorebirds’ roosting places of shorebirds have been disrupted in the Bay Area, the massive urban regions that spread along the coastal southlands hardly provide a comforting contrast–San Diego seems to have spread to Santa Barbara–

Urban Regions in Southern California Coast

–but open space increasingly contracting across the nation, hemming in and fragmenting habitat as never before. If the greater population of Los Angeles’–3,795, 936 and approaching four million despite the threat of apocalyptic fires–exceeds all but ten states of the union, the crisis in political representation that this leaves the nation pales before the crisis of cartographic representation of a focus on built space, rather than on the dangerous abandon of curtailed habitat. If we map our own presence, we anthropocentrically map the anthropogenic world as if for posterity by building footprints and built space. Is this the most healthy map we can imagine to orient ourselves to the changing world?

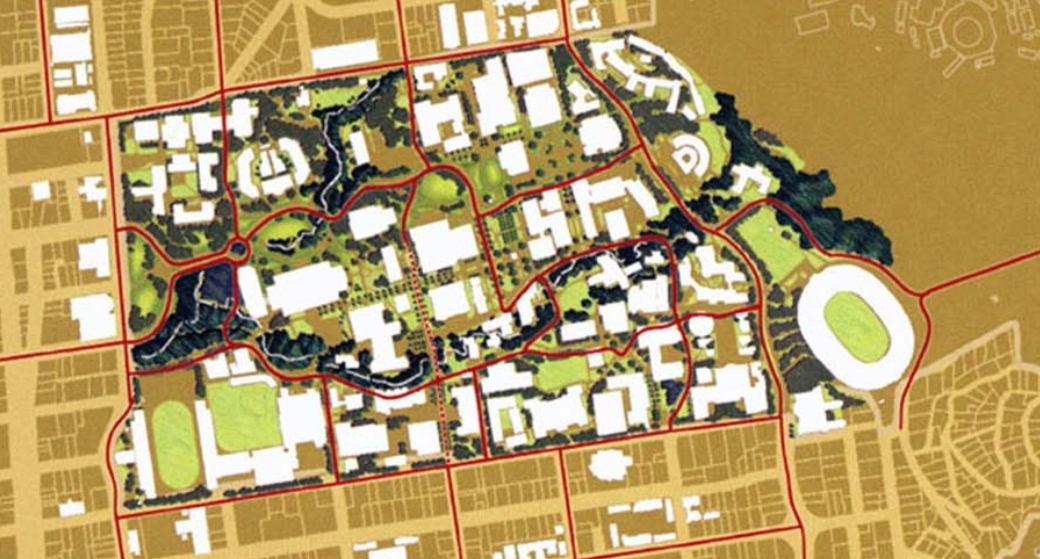

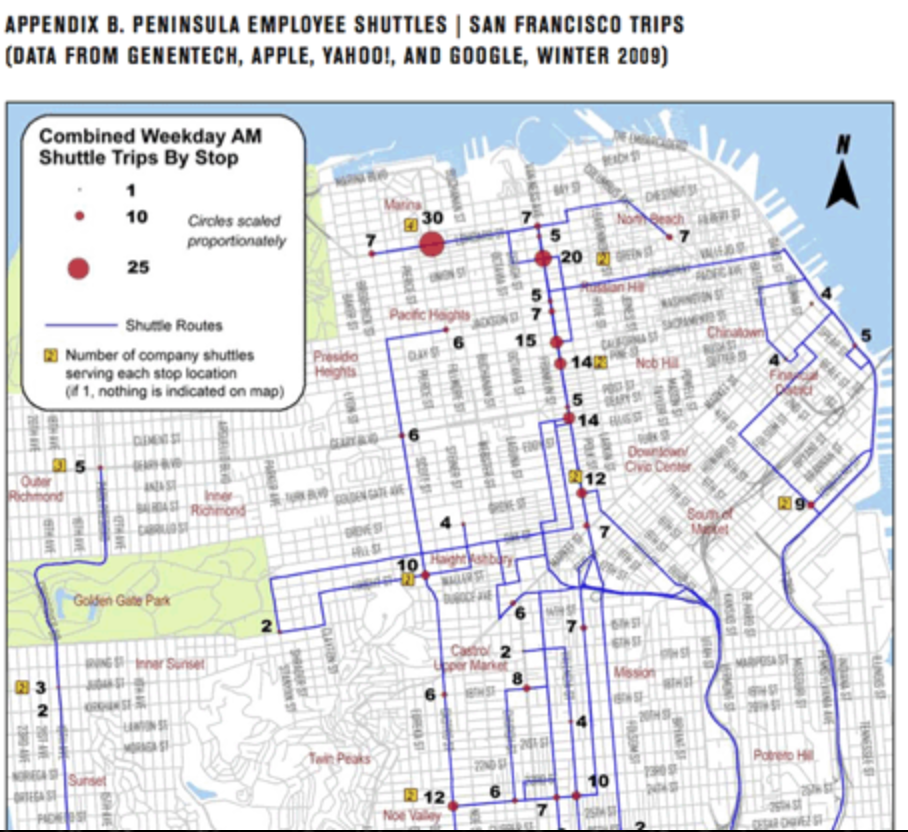

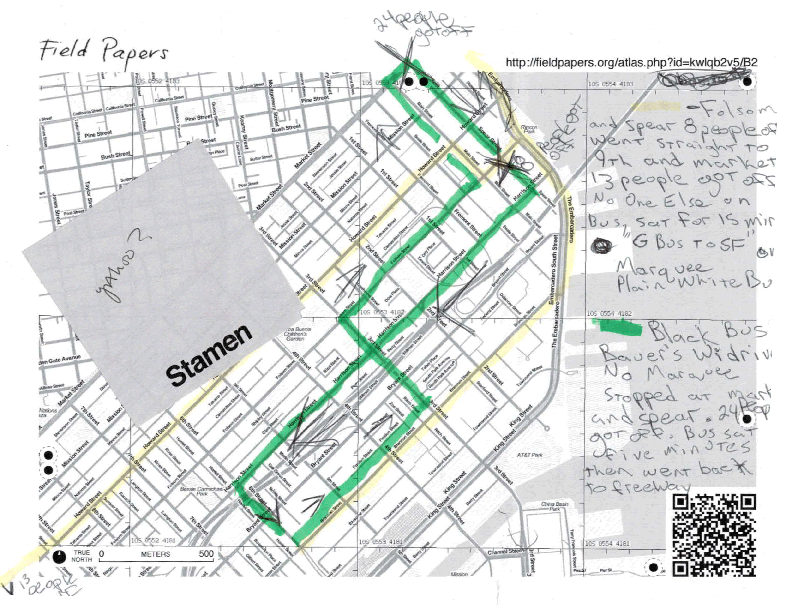

The attempt to create an interconnected network of transit roads comes at the costs of the access to nature and the habitat and migration patterns of much of North America. The mapping attempts to register habitat in San Francisco led a nonprofit, Nature in the City, to re-map the habitat corridors remaining in the city as a way of taking stock of this contraction by 2017, faced by the problem of the integrity of habitat in the city that has long defined by its relation to the wild and wild coast.

Urban Regions Nationwide in 2020 US Census

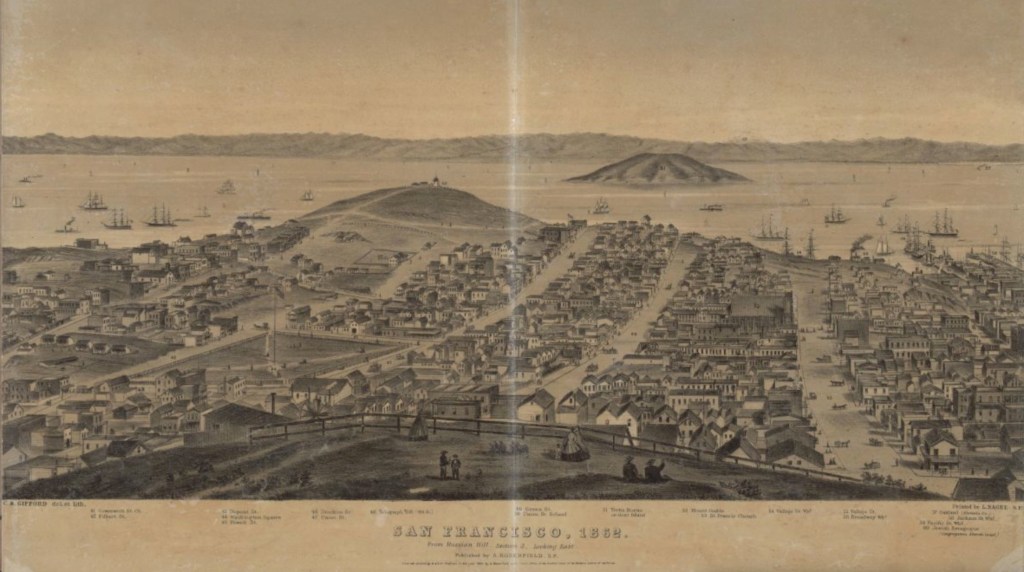

The moment of introspection or cartographic self-reflection is a worthy counter-map to the urban regions that the U.S. Census acknowledged,–and an anticipation of the need to affirm the existence of habitat in San Francisco. Habitat is too often overlooked, as the urban agglomeration of the Bay Area grows. If San Francisco was long a predominantly green city, majestically bounded as it is by the Bay and Pacific Ocean, dotted with parks and green space, although its development has been confined by faultiness, as much as by environmental strictures on urban growth and neighborhood improvement associations. He wasn’t talking about San Francisco, of course, which was long seen as a city amidst nature–as this print of a glass plate negative of c. 1910 from Marin’s Mt. Tamalpais looking East shows Marin’s shoreline a watershed of winding rivers and streams that fed the bay–

–before the Bay Areas wetlands were radically redefined by landfill to increase housing along the coastal shore, dense fogbanks left Angel Island barely visible in the bay from Mt. Tam, suggesting a habitat now lost of winding estuaries. The shifting of the current habitat over the past century raises problem of preserving pathways of habitat in urban life is pressing for expanding cities, increasingly paved and welcoming with garbage urban interlopers as crows, rodents, and stray animals, and the dogs invited in as companions and guests. Increasing visibility of murders of crows in urban skies suggest an actual invasion of flocks invading parks in downtown San Francisco and Oakland, larger that ever populations dominating and consequently compromising habitat, even if it looks the same: as the population of crows in Oakland unprecedentedly doubled from 2021 to 2022, after reaching a high the previous year, San Francisco birders counted count a record 2600 in one day in 2024, so teeming with roosts to be renamed San Franciscrow. As populations of corvids fill the streets and telephone wires for reasons form climate to increased garbage, one may increasingly lament the increased decline of habitat due to paved space and climate change,–and less often exult hearing the loud screech of year-round native residents as the California scrub-jay seek to reclaim its territory in remaining East Bay trees from the larger invasive corvids.

Ever-expanding urban regions raise pressing questions of islands of greenery and clusters of trees and open spaces in cities, often overlooked in the earlier mapping of expanding urban space. In contrast, the mapping of routes in which nature can continue to inhabit our cities is not only of ecological interest, but central to making our own urban spaces more biophilic, –friendly to residents beyond our own species–while we can, preserving and enriching open space on the margins of cities, in the face of the continued over-development and impermeable ground soil. To encourage habitat beyond back yards and parks, we need scaffoldings in built space all too often overlooked. We must consider habitat for wildlife beyond enclaves for the appreciation of human residents, available for the aesthetics of posed photos or instagram posts, or contact with the wild, but increased attentiveness to how we situate ourselves in nature, to try to rectify the rapid pressures of urban space, restoring imperiled habitat in urban areas of increasing density, where area of woodlands, fields, flowering trees, and open space remain at a premium, and most of our mapping tools have failed to register the scale of its loss.

For many years, building has disembodied islands of habitat in cities, leaving questions of the preservation of interconnected nature of throughways and linked passageways in the city of San Francisco is increasingly of concern. Even in the city by the Bay, between Bay and Ocean, the areas of viable habitat have shrunk, and stand to shrink more due to climate. We can only hope to foster and nurture such open space–shifting, even in and on the edges of cities, our perspective from urban residents, to nurturing space for and relation to nature that cities are able to accommodate, a question of cohabitation that is especially evident where the proximity to nature once existed in real terms–both on the wetlands of the Bay, but in urban space. The data tools to trace such habitat must be sensitive to the demands of species that we want to recognize, and to preserve areas for them to flourish, meshing a qualitative and quantitative view of cities, but also trying to consider the marginalization of habitat that is the inevitable consequence of the expanse of urban area. And notwithstanding the limits of LiDAr tools as to track remaining greenspace in cities by its disembodied data, the Nature in the City project uses the open areas of urban space to track the habitat that allows some species to continue to flourish by the bay, in hopes to reembody the vitality of built space.

The map is, to be sure, limited in foregrounding the dangers of invasive species encroaching in the tidal marshes of much of the Bay, as the green spartina that has filled local wetlands across over 70,000 acres of the bayshore lands, only recently restored, or the city, filled with increasing crows and seagulls. But in tracking charismatic species of the region, it hopes to orient readers to habitat pathways remaining urban space, inviting them to dedicate their own attention to their survival and pose pressing questions of what sort of city we want to live–and how we can continue to preserve nature in urban space, hoping to integrate where nature survives in San. Francisco’s urban space, and not only purely aesthetic sensibilities. It was ask us to consider the real reasons of the need to preserve art and cartography, integrating the qualitative records of urban environments and quantitative records of the ever-expanding outlines of built space, the maps is also a chart of the survival of habitat in our increasingly unwieldily urban regions. And if we decreasingly see the native scrub-jay calling in local trees to stake out its own territory encroached by invasive corvids, the preservation of islands of habitat trace important forms of resistance to paved expanse.

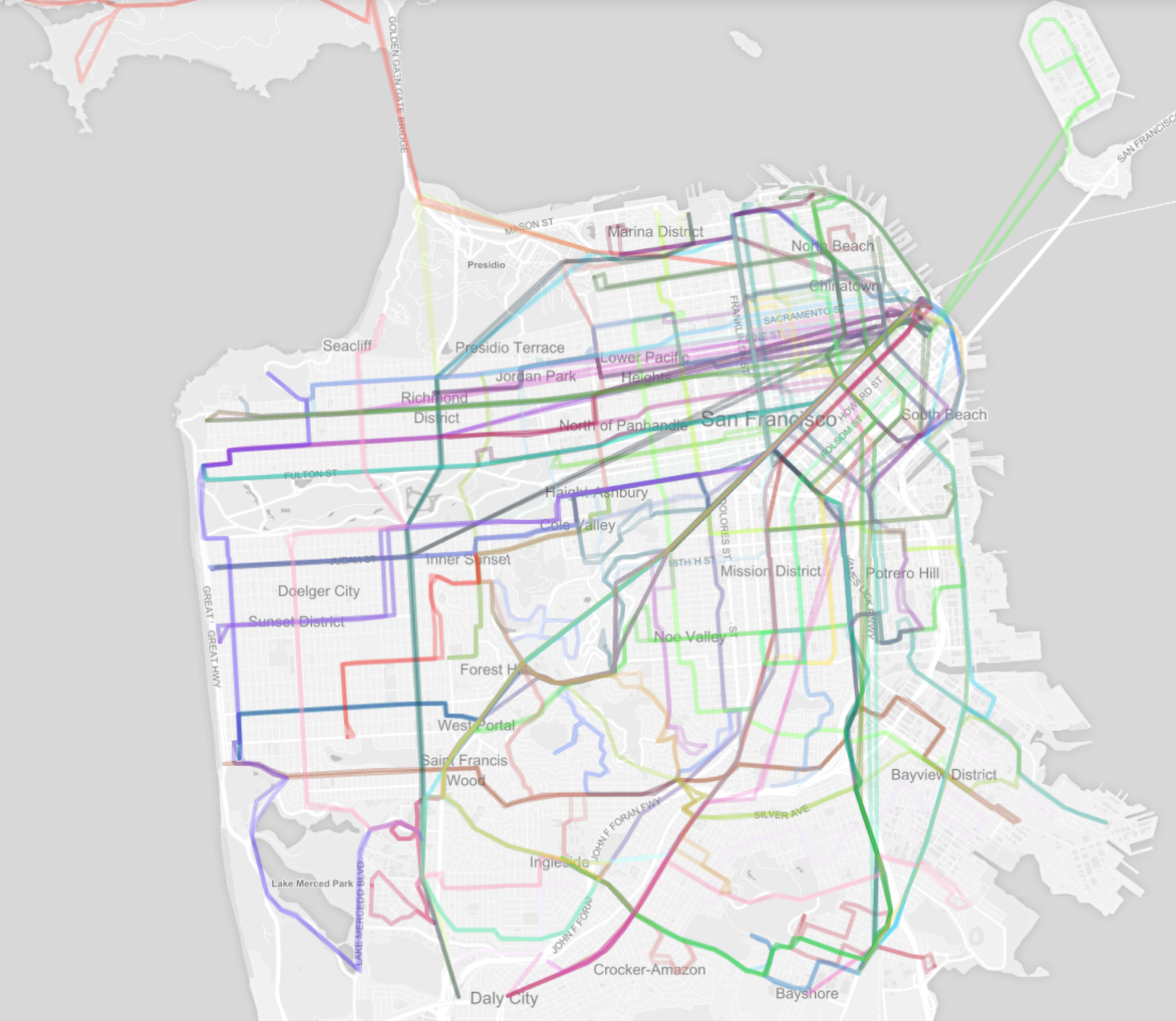

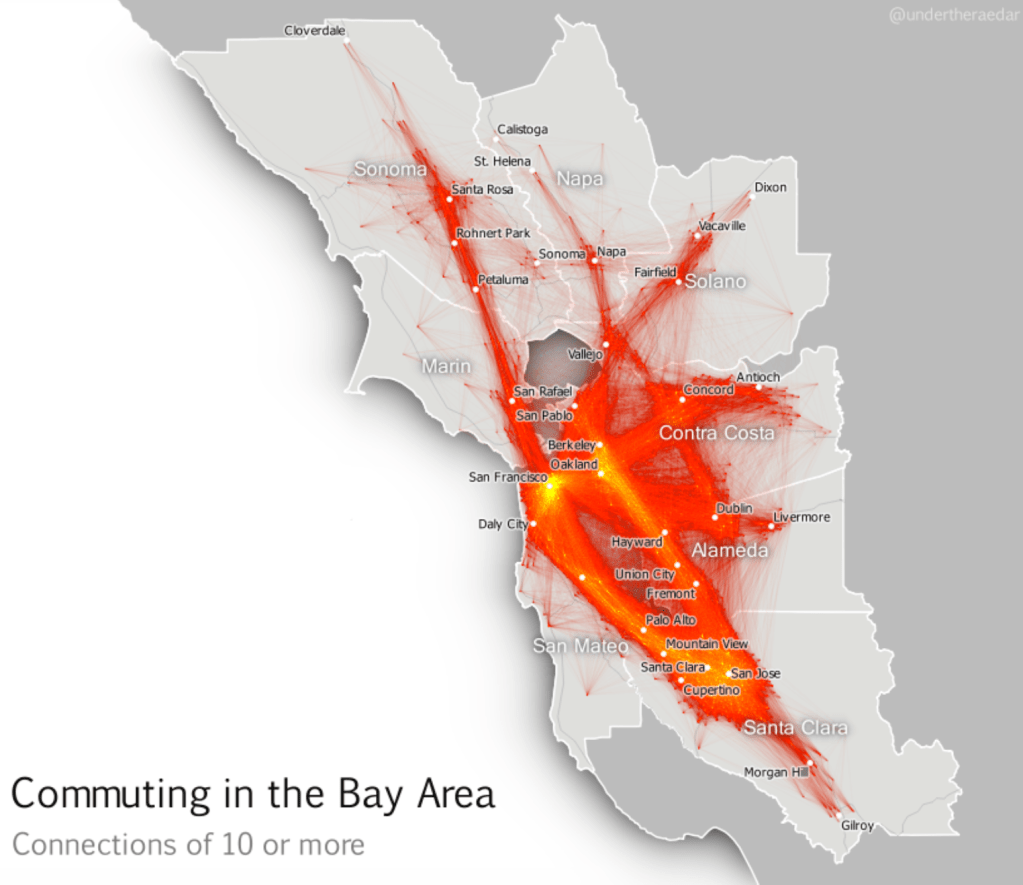

1. One real (cartographic) aspiration is to situate ourselves in a world to understand our relation to it, as the Bay Area’s paved sprawl became mapped by 2015 as a loci of traffic for commuting, more than a lived surface, dominated by commute routes of impermeable surfaces. The Bay Area has indeed become a mega-commuting area, a metro of some 7.5 million, almost as large as the 8.258 million in the five borough of New York City, the extent of whose commuting may suggest the primary nature of connectivity of paved roads, rather than spaces of animal habitat.

AlisCommuting in the Bay Area, 2015/Alisdair Rae

Far more likely is it to see the migrations of animals from an Aristotelian perspective in which animals are non-thinking actors, the commuter interconnections allowed on paved surfaces and public transit offering a primary nature of interconnection by which the Bay Area is immediately understood as a coherent unit. The abundant environmental datapoints on San Francisco’s actual animal habitat provides a possibility of mapping the continued presence of natural wildlife the city is permeated. The remapping of San Francisco’s actual nature provides, it is hoped, maps to help appreciate and even preserve the connections of animal habitat that have survived the Bay Area’s expanding footprint of impermeable ground cover, even if paving has pushed the presence of nature farther away from the primary lines of commuting, the hope is that the interstices of the natural world might still be able to survive. Indeed, the securing of interconnections and passage ways for nature is needed to ensure the continued vitality of urban areas as habitats, and prevent the further fragmentation or division of spaces wildlife is. able to exist and flourish.

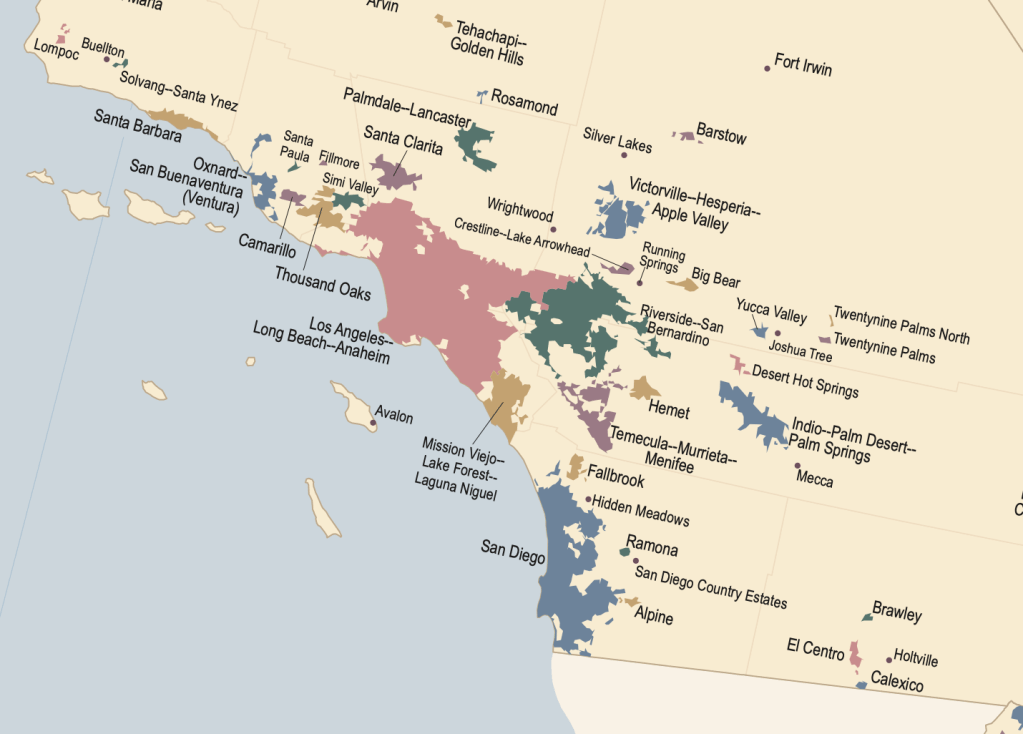

If we imagine interconnections of the Bay Area by analogy to transportation infrastructure, we might approach a deeper understanding of the migration patterns and natural presence that continues amidst the growth of ground impermeability and urban footprints that changed the ground cover and distance from the rocky outcroppings on which this family is elegantly paused on what seems a weekend jaunt. Any deep dive into San Francisco’s tie to nature, after all, starts from he sea–some fifty daily ferries by the 1930s, shuttling fifty to sixty million passengers transbay yearly, a quarter of a million being ferried daily to make landfall at the Ferry Building from hundred and seventy ferries, or traveling along the ferries that used to carry drivers on the first transcontinental motorway across the nation, the Lincoln Highway, and ferry them from the end of the Berkeley Pier that jutted into the Bay.

The deep structures of Bay Area before the Bay Bridge and Golden Gate reshaped webs of transbay travel, and to reconnect to urban ecology. Not only for reasons of public transit did Lewis Mumford bemoan the foreclosure of a relation to the rich ecosystem on the bay waters the Bay Area accepted in budding a bridge linking Oakland and San Francisco, which sent “a once unnecessary volume of private traffic between them, at a great expense in expressway building and at a great waste in time and tension, spent crawling through rush-hour congestion.” The volume precipitated a demise of past public transit webs, hardly resolved by the tunneling of the Bay Area Rapid Transit, but present in the old postcards that preserve the deep blues of the urban skyline in ways we hardly see at times from a bays whose coasts are spanned by three expansive anchored suspension bridges.

Cross-Bay Ferry Transit in San Francisco Bay and Ferry Building, Post Card sent 1930

But we have hardly begun to map the compromise not only of our relations to the huge range of avian life that the bay supports, and the range of birds who arrive from land, but the support that the Bay still offers marine life that leads whales and dolphins to enter the bay. These spaces are increasingly important to map, and map from the prospective of the collective intelligence of species, as much as the urban footprint of the city’s built space. This is true given the precious nature of the proximity to the wild spaces of oceanic expanse. and the interconnectivity that for so long distinguished the Bay Are from other urban areas. As ecologist Hugh Warwick notes, at a time we are facing an unprecedented fragmentation of habitat, it is incumbent to preserve spaces for interconnection crucial to species in an era when the world, increasingly shaped in unavoidable ways by the near-ubiquity of human presence, isolating islands of habitat to deleterious effects.

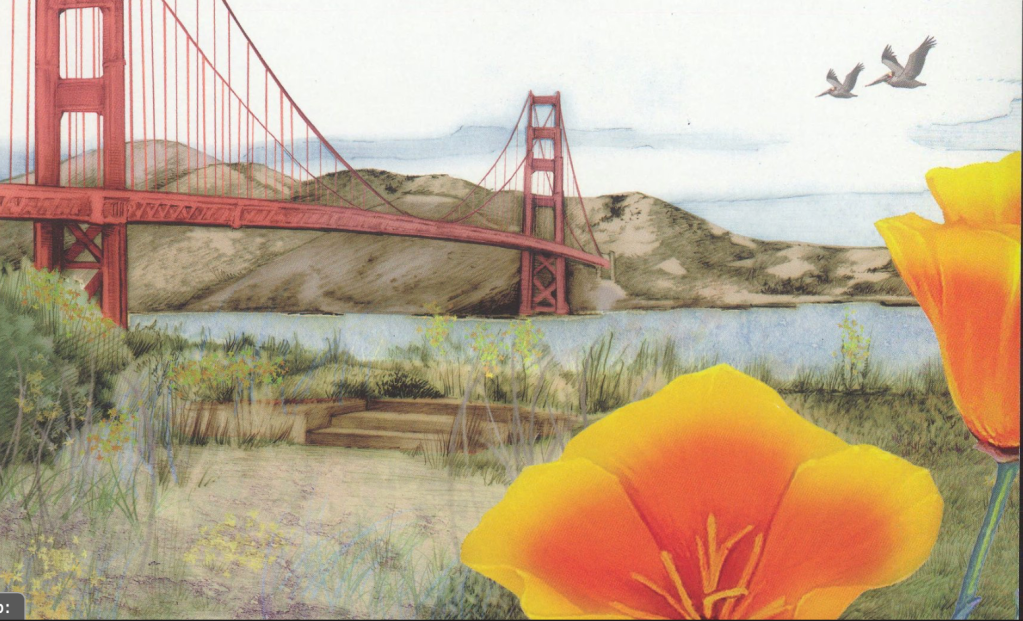

We move farther from the water of San Francisco Bay today, but the data maps of the access to lived habitats both onshore and offshore around the Bay in the mapping project Nature in the City began in 2005, and is currently available with enhanced LiDAR data in its third edition, to map the benefit of tracking and preserving habitat in an overbuilt world of increasing human footprint. The map has the uncanny and needed ability to focuss attention on we do daily, noting trails, natural scenery, and habitat as well as charismatic species to help cultivate our relation to a natural surroundings. And if this blogpost may seem unduly long, it arose from a deep appreciation of how the map seeks to offers a refreshing reorientation to our urban spaces, speaking to possibilities of preserving the access to nature and habitat cities might be able to offer. As we face the danger of a vision of the city whose homeless request seeded bagels to feed to birds, it is strong testament to the importance of preserving some access to “nature” among the people who live on the city’s streets, and seem to be starving for it on a level with their own daily bread. Isn’t the problem of how to make our cities more appealing and nourishing part of what increasing study of urban ecology and preservation of urban habitat about? Isn’t the problem that the collective knowledge by which species return–from migrating birds to other wildlife pressed out of their earlier ecological niches–in maps whose edges, polygons, and datapoints are increasingly defined in exclusively anthropocentric terms? The cover of Nature in the City’s third edition shifts attention from the built city to the edges of the city’s place in nature, magnifying the habitat and flora and fauna, foregrounding the residents and natural topography of what many see only as a built space.

Nature in the City, cover of third edition (2018)

We have of course only recently been determined to map urban health in new ways by access to nature in credible ways. Although the pleasures of open-air transit across bay waters gleaned in from tinted postcards, that suggest the more expansive skies and seas of a century ago, suggest both a more open “sky line” and far more intimate relation to bay waters, an point of departure to take stock on the persistent presence of nature in the city by the bay, and indeed to consider the different notion of its inter-connection, and why these interconnections are so important to cultivate, experience, and continue to preserve–not only in its rich shorelines but the dynamic vitality of its shores, parks, and the survival of its still rather plentiful unpaved areas, by focussing on the charismatic species that fill the urban space, whose habitat we may risk overlooking. Despite the limits of LiDAR sensing, the green spaces of the base map for this map suggest the areas of vital habitat that survive in the city, and the wildlife corridors they create, as if to undo the anthropogenic focus of most maps on built space. If that space was, uncannily, and unintentionally if with some surprise rediscovered in the pandemic, as increasingly audible birdsong filled many of the parks with the receding of much anthropogenic noise, the map offered a template to reorient ourselves to urban life and to take another look at built space.

We often sense nature only through the calls of owls and morning doves, and increasing number of families of crows searching for food, is there not a therapeutic benefit of trying to map the relation to natural habitats across the ever-expanding ecological footprint of urban space, even as so many commuters daily drive to and around San Francisco in our cars, more than by foot? Even if the massive freeway once designed to run along the bay was cancelled, only by mapping the resilience of a relation to nature can we take stock of the rich biodiversity that exists in the city, in hopes to cultivate it both on the ground and in our minds. And if the wildlife that is increasingly mapped in the city have been mapped to suggest the fragile nature of its relation to the wild, it also shows the continued porous natural presence in the city, encouraged by parklets, green spaces, large open fields, and a connection to the water on three sides.

The place of nature of San Francisco may have constricted, but cartographers have recently realized its importance to map. If measurement has been outsourced to numerous devices–from not only height and weight, but caloric intake, income, carbon footprint, and racial identity, the mapping of the proximity between nature and the city in the Bay Area is concentrated in San Francisco, bound by beaches, hills, and habitat. As a Midwesterner, Gass was aghast at what passed as “nature” for city-dwellers, marveling dryly at their lack of consciousness at their reduced collective relation to a natural world: “Nothing can live and remain free where he resides but the pigeon, starling, sparrow, spider, cockroach, mouse, moth, fly and weed, and he laments the existence of even these and makes his plans to poison them,” Gass writes with the relish of his perspective, before adding onto the jeremiad his final punch: “His parks are potted plants.” The reservoirs of green that interrupt the urban footprint of San Francisco are hardly afford a coherent ecosystem, but relations of urban and rural that animate so many west coast cities have made it urgent to remap relations of “urban” and “rural” that were once clear dichotomies, pushed by the increased absence of open spaces that once surrounded cities like Portland, Seattle, or San Francisco.

2. The natural residents of San Francisco do not include rats (who arrived in the United States only in the 1800s), if it is the second-most infested in the state, crows, residing in in the Bay Area since the 1870s, if only recently did birders count 2,300 in but one day, creating a cacophony of squawks from big murders that conjure Alfred Hitchcock in city trees, or other opportunistic foragers as the seagulls, but the city’s infrastructure accommodates a considerable wild. If the squabbles of western seagulls in San Francisco may harass the pelicans, the territorial birds and rodents are rarely countered as protected or sensitive among the large numbers of declining species many have hoped to encourage in urban habitat. As even population of the American Crow is in decline, we are caught in multiple catastrophic states that have been released upon the world, of which the declining avian population of the nation is a bellwether.

Even as gull populations decline in San Francisco–from the ring-billed to the western gull, if not the California–with the American Crow, Avocet, Cliff Swallow, Willet, and Forster’s Tern, the niches of wildlife habitat that the city offers is especially important to preserve, as essential grasslands and wetlands are being lost to development. Even as not only bird watchers hundreds of murders of increasingly ubiquitous crows are descending on the Bay Area, more than other bird populations, as other American urban environments, amidst the massive incursions of corvids, bird populations in green spaces offer a valued ways of sighting nature in the face of the startling declines of American crows, starlings, song sparrows, willets, avocets and wigeons in San Francisco. The sight of corvid populations seeming to swarm trees, telephone wires, and church steeples appears so aggressive to be straight outta Hitchcock, an arrival so massive to intimate deep disturbances of anthropogenic worlds, as cries of sizable populations of urban scavengers stake claim to streets, telephone wires to the apparent exclusion of other, smaller, avian species, making permanent claims on urban space. Only occasionally does one hear the indigenous scrub-jay, atop its own tree branches, screech as if to stake out its own claims to territory in the face of other corvids.

Robert Alexander

Indeed, if the Golden Gate Natural Recreational Area, a Marin-based park that hosts two thousand plant and animal species over nineteen distinct ecosystems shares the largest boundary with an urban environment of any national park, the focus on conservation that brought together what has been heralded as a “new urban park” was created by cobbling together public and private lands that redefined the value and relation of the constellation of interconnected parks to urban space that presents a compelling model for a new urban park” outside of the growing city, and a new relation of nature to the city than Gass experienced. Awareness of the biophilic needs of urban inhabitants for contact with urban greenspace, that has prompted active redesign urban environments in an increasingly overpaved world. Recent evidence on the benefits by which greenspace reduces stress and mental illness makes the question urgent. And the recent mapping the presence of “nature” in the city’s urban environment cannot be reduced to parks alone. Biophilia is not just the self-congratulatory boost from the mutual admiration society of dog-owners, eager for inter-species contact, but a sense of creating habitat for other animals, an inter-species appreciation of occupying space. And perhaps our opportunities for creating wildlife habitat is increasingly important in an era of increased anthropogenic change.

As our contact with nature and the natural is endangered or at risk of deterioration, the perspectives that open space around San Francisco offer on the ravines of built space make the case for remapping urban space and open space that the nonprofit group Nature in the City rendered in their 2017 map, as a necessary and important counter-map to the data maps that privilege the permanence of built space or the expanse of built space or its human density, but how habitats intermingle with the built environment of a city like San Francisco, shifting a tacit prioritization implicit in all maps. San Francisco is, of course, the beneficiary of the huge area of the nearby Sacramento Delta, through which over 40% of run-off from the Sierras have long flown, bringing with them sediment from the mountains that flows to the sea, creating alluvial deposits that have made it a nexus for fifty mammal and fish species, from salmon to striped bass to sturgeon to steelhead trout and endangered smelt, and a stop on the Pacific flyaway from Canadian geese to sandhill cranes, and a habitat for over two hundred bird species, twenty reptiles and amphibians, attracted by sediment-rich marshes of the watershed’s historic wetlands and open lands. Can we map their presence in the city nearby? Or do we not have to do so better than in the past?

If the threat of habitat loss is ranked by the UN Convention on Biological Diversity as among the greatest of threats to biodiversity, along with invasive species, climate change, and pollution, a map of remaining pathways and corridors of habitat in cities like San Francisco provides among the most relevant of orienting benchmarks for our time.

1. The recession of the “city” in their recent 2D map–just barely visible as a skyline a full three quarters across the view form Loma Alta Open space, in Marin–the Nature in the City map inverts the equation, by asking us to view the city in its relation to surrounding habitat that still presents a living ecosystem that enters the city’s paved streets.

Long before politicians railed against cities, asking where the heart of the nation’s heart lay, this icy put-down summoned the identity of the interior to dismiss the paltriness of urban parks as poor replacements for the nature world. But the if the built centers of San Francisco have grown in recent years–both in its downtown skyline and neighboring Oakland–as any departing airplane can see–the maps we make of our changing cities demand we attend to how they invite us to explore and navigate urban space in all its dimensions–including the role of the city as an ecosystem, as much as a built structure.

We bristle in San Francisco at the dismissal of our built environment, or verticality as a measure of cosmopolitan urbanism. From the seat of the departing plane, one might forget that the city not only borders significant greenspace across the Bay, but that San Francisco and the East Bay are living habitats–if ncreasingly sensitive as a site of potential habitat loss. Greenspace demands preservation as an ecology that many city-dwellers often fail to note.

As increasingly mindful outfits like the Nature Conservancy seek to preserve a public consciousness of the need to mitigate incursions of urban areas into the urban greenspace, we might ask not only how to convince public planners and developers to be more conscious of such incursions–and the serious problems that they create for fire, as well as compromising ecology and habitat. While the most rigorous conservation plan. based on the Bay Area “Greenprint”–to be extended to all California–calls attention tot nearby critical ecosystems demanding protection by a”Mitigation Wizard” from the sightings of the most at risk species’ to stress the sensitivity of their habitats–

–the intersection it creates between habitat and potential extra-urban growth is designed to better help us negotiate the futures that the Bay Area might meet. Tracking the density of species in critical ecosystems lying in proximity to the Bay Area’s urban agglomeration, different levels or criteria of conservation can be entered against current natural science observations of sensitive habitats of up to one hundred species around San Francisco’s wetlands, forests, and grasslands that can create a dialogue between areas ecological sensitivity in close proximity to urban growth. The hope is to offer a baseline for mitigating the effects of urban growth–and to elevate those concerns to a level comparable to the attention to property that is increasingly seen as vulnerable to sea-level rise, the aridity, fire risk or soil subsidence as consequences of warming and temperature rise, acknowledging local ecosystem integrity as consequences of anthropogenic change.

Continue reading