The Gaza War is not for territory, but is explicitly about erasing sovereignty. And much of the war, if fought above ground, is aiming at what lies underground, hidden from sight, and not on maps–even if we imagine that we might be able to map the damage, disaster, refugee flows and loss of life as well as destruction of structures across the Gaza Strip in ways that are truly impossible to process. This data overload, or information overload, responds to a proliferated media coverage of the disastrous war, but is also difficult to relate to the terror of the unmapped underground network of tunnels in Gaza, and the ways that the tunnel networks have been a reason for the terrible escalation of aerial attacks that have created such humanitarian catastrophe across Gaza and the Gaza Strip. As much as a war for territory, in a traditional sense, the Gaza War is almost one of purification–not purification in a religious familiar from the Middle East of the Middle Ages, but of the possibility of purifying the region to ensure Israeli national security. And as a war of purification, it is almost fitting that the metaphors of vermin or unwanted animals dehumanize the enemy, as if a negative of actual residences or humans with rights. We are in a pre-Enlightenment discourse that denies all concepts of rights, or

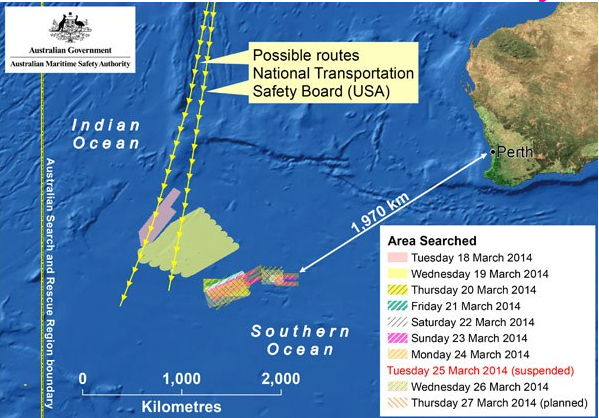

The tunnel network that evolved from an infrastructure of smuggling to a means of tactical defense has become a target that is quite elusive: if the tunnel network beneath he Gaza Strip was underestimated quite dramatically at but about 400 kilometers after October 7–reflecting boasts of an Iranian general “Hamas has built more than four hundred kilometers of tunnels in the northern section of the Gaza Strip,” the estimated underground passages became a basis to underestimate the scale or intensity of its destruction. Indeed, the shock at the scale and technical quality of the underground network has been slowly grasped as far more difficult to target, as its size has since February greatly expanded to seven hundred or even eight hundred kilometers across the entire Gaza Strip. The tunnel network provides both a significant military and tactical challenge,–but one unable to be easily targeted or eliminated, even by existing mapping tools, flooding with seawater, the engagement of robots with facial recognition, or the location of hidden networks and their destruction. The tunnels under Rafah that are feared a network for smuggling arms from Egypt to replenish the arsenal of Hamas–underground tunnels dug under civilian neighborhoods that served as “terror nests” where Hamas commanders retreated–allowed the infrastructure of civilian neighborhoods to be destroyed, while the military infrastructure of Hamas remained intact.

Destroyed Buildings in Gaza Strip, November 5, 2023/Atia Mohamed/Flash 90

The hidden, unmapped expanse of underground tunnels, which Israeli intelligence for all its capacities seems to have misjudged, has become a target that has evaded mapping or location, turning the destruction of tunnel networks into a game of whack-a-mole, even with the prioritization of tunnel detection and warfare tools. Meanwhile, hostages held underground are unallocated, leaving the Israeli army far more “blind” in its engagement with Hamas. The intelligence of the network has been repeatedly minimized by metaphors as it is animalized as a warren, a lair, a spiderweb, or a labyrinth, as if to suggest its animal like nature, promised to be dissmantled as a structure of evil–an inhumane warren, more than a site of human resistance. The engineering of the network that has been able to be reduced in metaphors has expanded as an achievement of engineering–“beyond anything a modern military has ever faced,” per the chair of Urban Warfare Studies, at West Point’s Modern War Institute, making the conflict far more than academic–and a focus of global tactical attention of the shifting terrain of future combat.

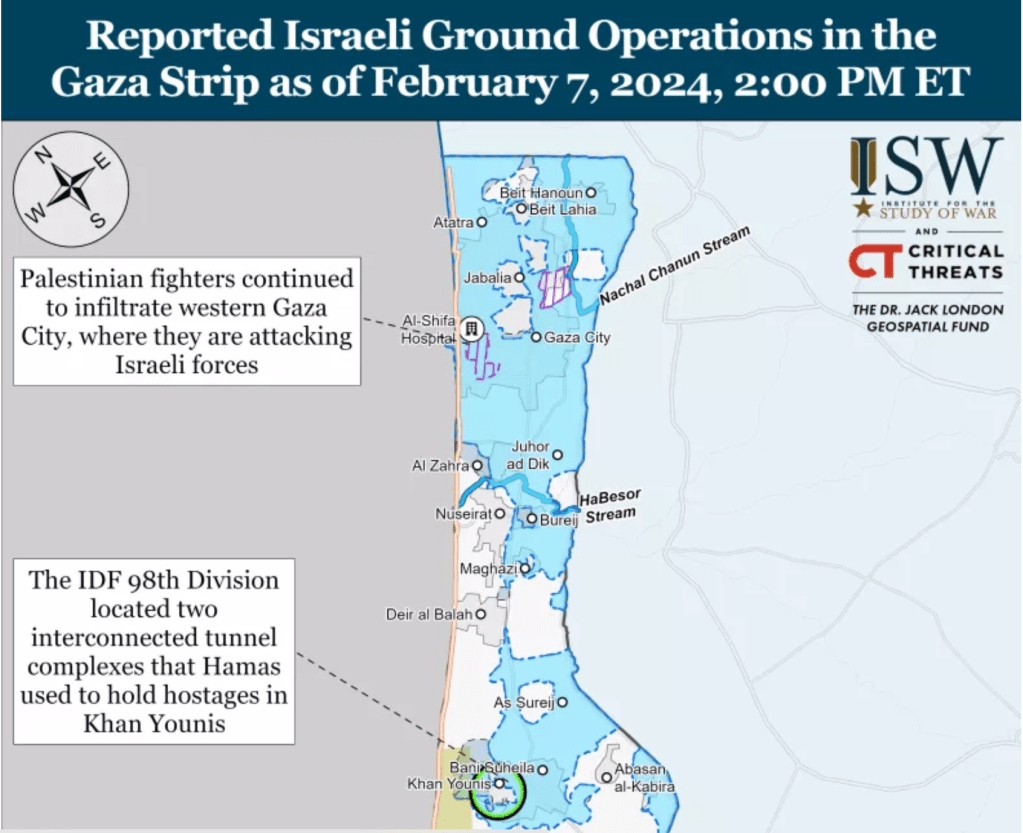

Meanwhile, it has only grown, as we have understood the existence of longer tunnels, fifty meters underground, as if underestimating the tools of engineering the warren, and the evolution of underground engineering that has allowed Hamas to dig in for the long war, making any lightning strikes impossible and only endlessly destructive. The destruction has been, as a game of Rope-a-Dope, infuriating Israeli Defense Forces, who seek to target an evanescent enemy; the Israeli Army tries to materialize its existence as a set of targets–even as the Israeli Army has issued repeated maps, in hopes to rationalize their expanding ground operations across an increasingly bombarded and devastated Gaza Strip, locating tunnel complexes where the hostages were once held. Is the war not really on two fronts, one, the human civilian casualties, who have been erased as “shields” manipulated by Hamas, and the true, hidden front, which is fought with a group dehumanized to the level of animals, not deserving of anything like a decent residence or shelter in the Gaza Strip?

The Gaza War was explained in no uncertain terms as the destruction of this hidden network in which the terrorists who planned the attacks of October 7 could be extirpated from the region of the Gaza Strip, as if independent from the humanitarian needs of inhabitants of the Gaza Strip, in a sort inexorable logic that leads to no apologies, but exists as an imperative that is the only narrative frame for bringing the war to its conclusion. “Dismantling Hamas’s underground strongholds in the north, center, and south is a significant step in dismantling Hamas, and it takes time,” we were clearly warned by Israeli spokesman Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari, in late December, 2023–aware of the intensity of bombing of hidden “nerve centers” of Hamas, but unaware of the visible brutality wreaked by the tremendous–and perhaps truly incommensurate–destruction above the ground. If Israel has destroyed many “cross-border” attack tunnels that extended some two hundred meters into Israeli territory both in 2008, 2012, and in 2018, the extent of tunnels that were celebrated in Al Jazeera back in 2014 for their ability to store weapons and shield Hamas leaders from air attacks as well as link the Gaza Strip to Egypt–and long designed a site of resistance to Israeli sovereignty.

Destruction of Tunnel Network Dug into Israeli Territory/October, 2018

For as the network has grown as the governance of the Gaza Strip has shifted, expanding as a form of hidden sovereignty able to endure attacks and escape Israeli vigilance and guarding of borders of the enclave. Although “mapping tunnels in Gaza right now is not going to happen,” the tunnels have become the elusive map of power in the Gaza Strip, a “big reveal” that has become the focus of the war, revealing the terror of porous borders that were echoed by the discovery of five Hezbollah tunnels on the Lebanon-Israeli border in 2018, in a military operation, that seems to seek to frustrate the Israeli Defense Forces’ charge to “defend Israel’s borders, since the formation of the Israeli Border Police in 1948, immediately after the foundation of the state of Israel–a Border Police who have long worn the Green Beret, signifying their status and crucial military role, symbolizing the “Green Line” drawn on the early maps of the Armistice of the first Arab-Israeli Wars of 1949, the pre-1967 border that have been taken as contravened by illegal sites of construction. If the Border Police have long imagined “peaceful borders,” the nearly 20,000 structures built along the border of the Green Line were viewed as a “ticking bomb” in the West Bank after October 7 invasion.

Years before the invasion, fears were raised by the scale of apparent bloom of illegal projects of Palestinian construction in Judea and Samaria, assembled by a combination of GIS mapping and aerial photography, as well as field work, that tracks the huge increase in “illegal” construction in 2022 in areas of Israeli jurisdiction by 80%–some 5535 new structures being built in 2022, an 80% increase over the construction in the same area in 2021, that are far from makeshift shacks.

Construction of “Illegal” Palestinian Housing in 2022/Regavim

The construction of what has been deemed strategically placed projects–and can be shown as such in maps of the region above–seem designed to hem in the settlements of Israelis around the so-called “Area C” of the Oslo Accords, if they might also be seen as overflowing the narrow areas allotted to Palestinians. But the huge construction project suggests an influx of cash, that might be seen as analogous to the creation of a costly network of tunnels by Hezbollah on the Lebanon border and in the Gaza Strip, as ways of challenging the stability of borders, and indeed the security of borders that has long been central to Israeli identity, and has become an accentuated topic of public concern in recent yeas–and least because off increased rocket attacks in Israeli territory.

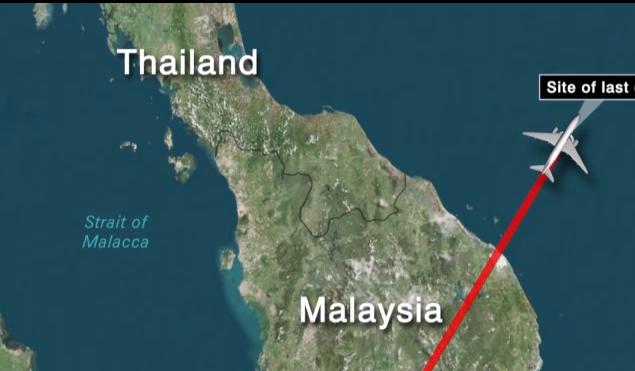

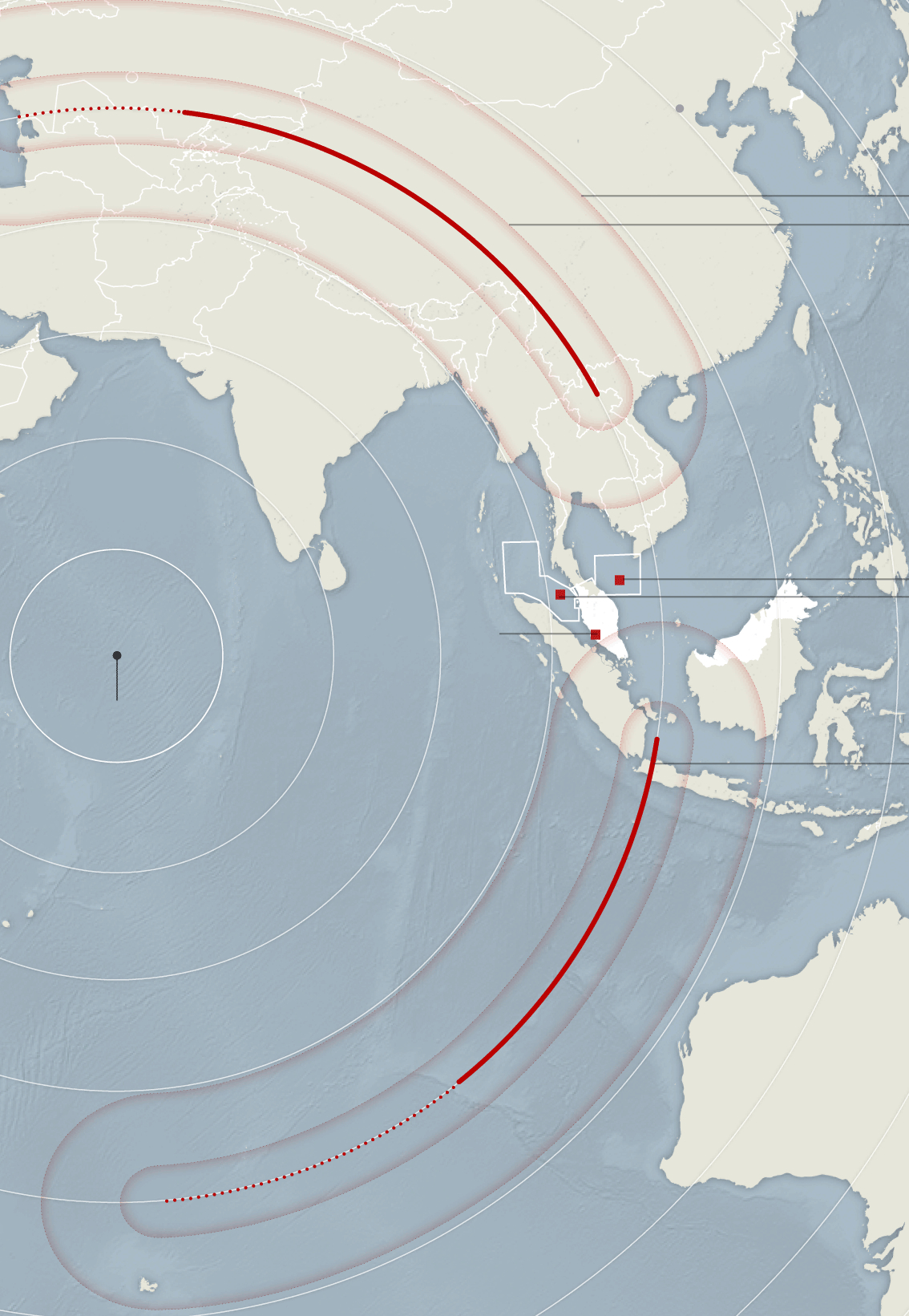

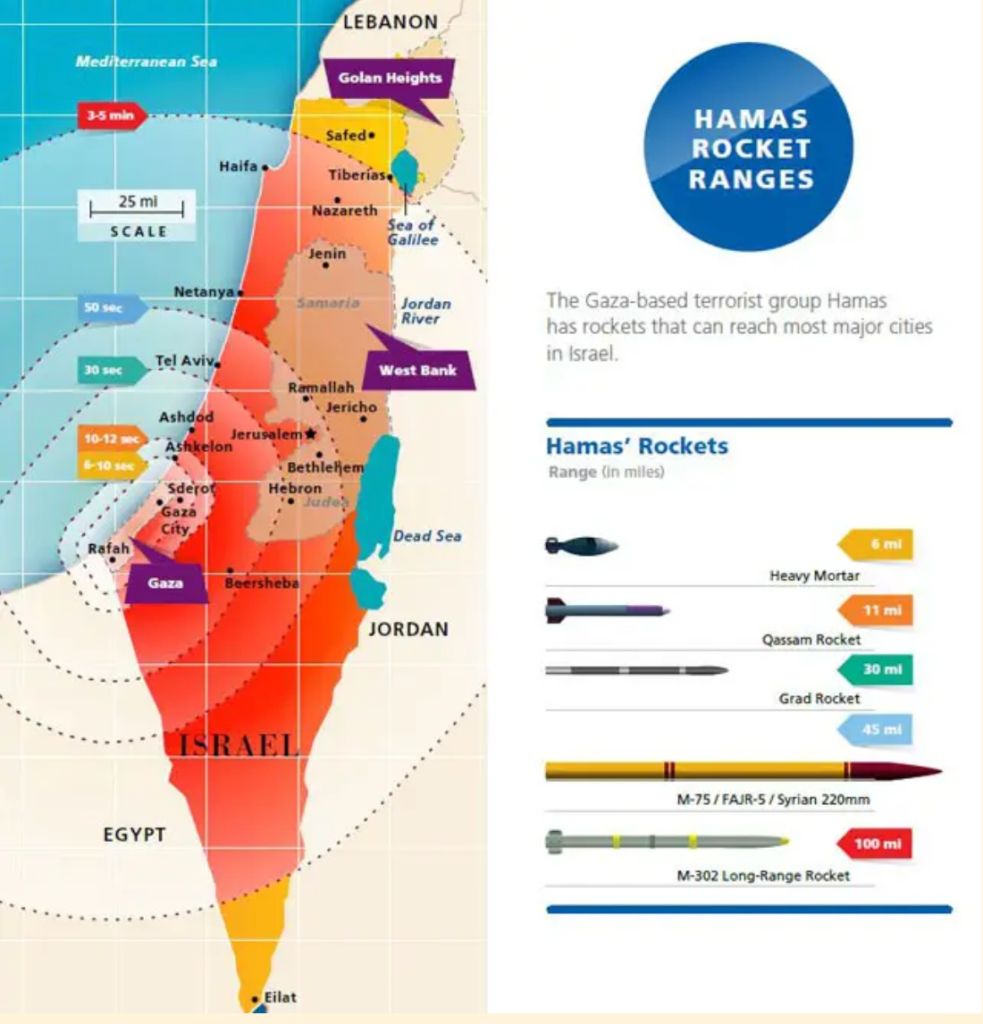

In recent years, the ramping up of cross-border vulnerability of unforeseen proportions has placed the nation on tenterhooks that rendered most major Israeli cities vulnerable from the Gaza Strip with the rockets of Islamic Jihad capable to reach targets in Israel one hundred and fifty miles away, and escalated fears of the increasing proximity of the Gaza Strip to Israeli cities–long before the raid into Israeli territory concretized the fears of cross-border vulnerability in nightmarish ways.

Rocket Ranges of Hamas from Gaza Strip, 2022/Jewish Virtual Library

The same alarmist catalogue of the weapons that were posed at Israel’s cities by a range of rockets from the international market–Qassam, Katyusha, GRAD, and Iranian M-302, M-75, and Fajr-5–were suddenly aimed by surrogates at ranges to reach m-and Israeli populations in Tel Aviv or Jerusalem–were mapped, of course, by the IDF itself, who are tasked to guard Israel’s borders. as an armory poised at most all of Israel’s cities, far from the Gaza Strip, a decade ago. But we had the illusion, or geographic imaginary, for a decade, that those dwelling near the Gaza Strip were as protected as anyone else in the nation, and did not suffer any special degree of vulnerability.

The Deadly Arsenal of Hamas,Israel Defense Force, 2014

map returned to tabloids and newspapers in Israel after October 7, questioning the ability to allow such intensive proximity was haunting the Middle East. The increasing density of the projects of technically “illegal” housing was not a proxy or basis for cross-border attacks, or for firing rockets. But the worry of destabilizing borders by occupying such “seam zones” on borders grew, as they seemed to reveal a long-term strategy after the invasion of October 7, not even twenty-five kilometers from Gaza, and was worried in the days after October 7. The fears Israelis would be hemmed in would be potentially explosive if Israeli military presence in Area C was withdrawn, as in Gaza Strip from 2005; any Peace Talks, it was feared, that would sanction a Palestinian State would have to lead to recognition of their legality and potentially set the stage for a similarly catastrophic invasion of borders, as the rhetoric of an imperative of securitization grew.

Construction of “Illegal” Palestinian Housing in 2022/Regavim

They deep fears that the invasion of October into Israeli territory triggered and made palpable fears of a violation of Israeli boundaries in ways not previously imagined–and could only imagine after October 7. The fears that such an invasion could be facilitated by an existent tunnel network in the Gaza Strip the have defined the “goals” and prerogatives of the Israeli army to destroy, even if their danger is contested and not readily seen. And if we project such tunnels as a “satellite map,” we are preserving the false illusion that we even know their scale, or can “map” the network as part of the landscape–even if they are indeed part of the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East.

For the underground Islamic Jihad tunnels, lying far beneath the ground, and not able to be “seen” or mapped in any actual manner, the tunnel network remains largely figurative, spectral, and assembled in partially from old surveys from previous invasions of the Israeli Defense Forces, offering a poor proxy for targeting, but providing a terrible image of a hidden enemy, unseen and impossible to measure. As the earth that as extracted to construct the tunnels was dumped offshore into the Mediterranean, making it difficult to quantify the scale of earth excavated by tunnel-makers, or the scale of a network that has offered a basis for the Palestinian terrorists in the Strip to survive aerial attack, and indeed to keep the civilian “hostages” taken from Israeli territory under concealment–even as the “tunnel network” is also widely mapped in international news.

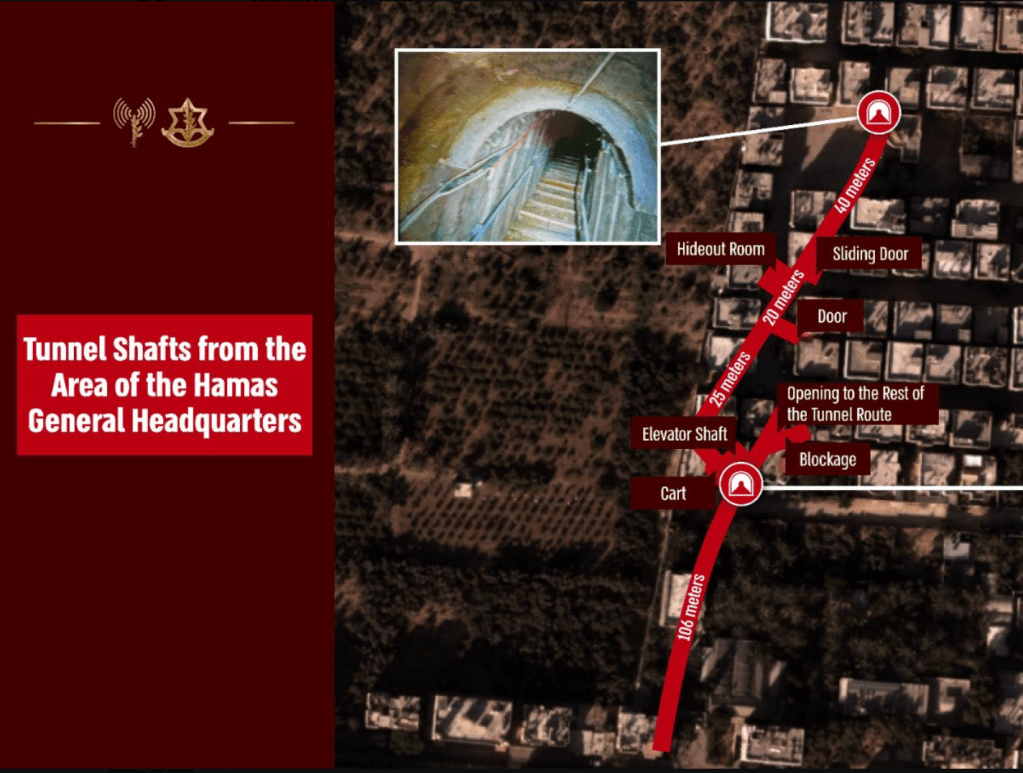

If we are shown “Hamas’ Secret Tunnel Network,” “Hamas’ Tunnel System,” or “Gaza’s Underground Labyrinth” in respectable news sources, and “Hamas’ Huge Underground Network” in somewhat salacious terms of more popular news sources, the secret spaces of these underground caverns have a truly Alice in Wonderland-like quality of an underground storehouses, or hidden hideouts, worthy of evil comic book characters, and apartments, tied to shafts, elevators, and other concealed openings, existing under the street plans of the city, as a “city beneath a city,” and even imagined as a future terrain for military combat, hand-to-hand wars, or the future zone of conflict.

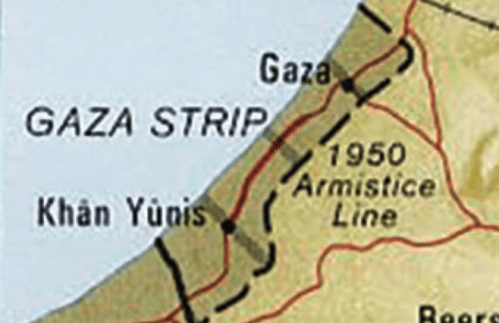

1. The tunnel network is a remapping of the boundaries that are formally imposed around Gaza Strip. Although it is odd to see them as a form of counter-mapping against the claims to sovereignty in Israel’s boundaries, they are just that. For the tunnel network, if begun as an economic necessity, has been expanded and exploited to as a basis to deny the limits formally imposed by the 1950 Armistice Line, which has perhaps provided the basis for the energetic chants heard in public spaces across the Western world, to Free, Fee Palestine, that invest a coherence in the currently occupied territories as an enslaved region that has been left at the mercy of a “terrorist state.”

The Armistice Line concluded after 1948 Arab-Israeli Wars did not invest territoriality in a region–

–but recorded a status quo of sorts later preserved in the Peace Accords and 1955 Armistice Agreements at the height of the Cold War, a stalemate of sorts between global powers, to be sure, understood and enshrined in maps along the original reference points of a historic Palestine Grid–

1950 Armistice Line and 1955 situation of Gaza, Mapped within Palestine Grid

–whose construction was, to be sure, the legacy of a colonial or quasi-colonial movement, drafted by the English on the model of their own OS maps as a way of preserving the spatial organization of archeological ruins, but that have created a framework to what is misconstrued as a religious war.

The provisional line that was drafted at the foundation of the State of Israel, and provided the orignary boundaries of the state that was guarded by the IDF, as the persevered the territory that was newly mapped in terms of a UTM projection that extended, as the timeless liturgy of the Prayer for the Israeli Defense Forces suggests, and increasingly patrolled by IDF forces in order to contain threats to the security of Israelis living near the region, as well as the increasing number of settlers near the border. The mapping of the expanded boundaries of the Gaza Strip to deny access to the outside world or to Egyptian neighbors is nothing less than a classic micro-macro point of tension in global geopolitics–“over our land and the cities of our God, from the border of the Lebanon to the desert of Egypt, and from the Great Sea unto the approach of the Aravah, on the land, in the air, and on the ground” in existential terms–even if the 1994 construction of a barrier between Gaza Strip and Israel was stated to be provisional, unlike the current claim to have created an “Iron Wall” that offers no clear basis for future discussion–and indeed seeks to force future negotiations from a position of power.

United Nations Palestine Map Showing Armistice Agreements between Israel& Lebanon, Syria, Jordan & Egypt, 1949-50

The current construction of a heavily fortified “Iron Wall” has provided the current crisis in which the framing of Israel as an occupying power has morphed into charging it as a terrorist state–a reflection of the very terms that Israel’s government charges Hamas, and given the events of October 7, seems to offer ample justification for doing so. The effective boundaries, however, provide the clearest basis for containing terrorist incursions has however not served the state.

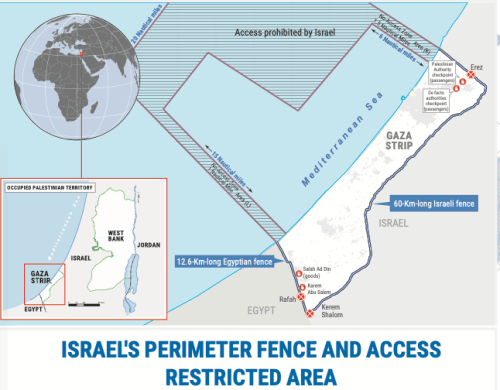

The “Green” Line has been an internationally recognized boundary of the Gaza Strip, defended by the Israeli Defenses Forces as such, never intended to be designed or rendered as a border of sovereignty, but has been construed as a political or territorial boundary in local and global geopolitics. If drawn independently from claims to rights of Palestinians, a question kicked down the road to an unspecified date for future resolution by the global consensus, increased fortification defense of a militarized barrier that maps the Green Line as an actual border–

–that hinges on the perimeter fence. If it is design to limit global traffic it is unavoidably now treated as a border that demands protection to protect “our land and the cities of Our God,” as the prayer written in 1967 has it, that have perhaps enshrined the dating of the time-stamped “1967 borders” or “pre-1967 borders” as the basis for a “demilitarized” future, a fact that might be datable in terms of history of globalization–hearkening back to a time when the United States was an engine for almost half the global GDP, before the United States abandoned the gold standard, and before the waning of American global economic dominance of the postwar–the era in which the Universal Transverse Mercator was adopted as a model of a smooth global surface.

The network of tunnels that were dug under imagined border revealed its first porousness in 2005, with withdrawal of Israelis and Israeli troops from the Gaza enclave, and the expansion of a tunnel system that Israel had tried to contain. Increasingly seen as a threat to Israel’s sovereignty, the network has become a way of testing the borders that have emerged in an enclave once in 1955 tied to Israel by roads; the, contesting the so-called “Green Line” that divided Arab from Israeli sovereignty since 1950. If it is a sticking point in Palestinian peace accords, it is the stubborn site of the only survival of the old “Green Line,” the last line standing, that was set out in the 1949 Peace Accords, as a new “underground reality” emerged, not on most national maps, proved a way to erode–quite literally–a map seen as engraved in stone, contesting the original “demarcation line” seen and equated as an “original sin” of the “Palestinian Question.” While territories beyond the Green Line were not incorporated into Israeli sovereignty, the growth of robust tunnels along the contested “Philadelphi Route” running from the Gaza Strip to Egypt, was perhaps the original robust tunnel to smuggle weapons to evade Israeli surveillance, underneath the “security belt” Israel claims as a defensible border, as the tunnels appear to confirm an actual terrorist threat.

Robust Underground Tunnel of the Philadelphi Route from Egypt to the Gaza Strip

The “belt” is not a national border, or an international border, but has become defined as a “security border” analogous to the status of the Jordan Valley, by tactical terms first defined by the General who oversaw the victory in the 1967 War, critical to Israeli security–if not for its territorial identity. The bifurcation of the security border and national boundary at Gaza has grown as the boundary of the Gaza Strip become guarded as a border of Israeli territoriality, I argue in an earlier blog post, shifting understanding of Israel’s boundaries and their guarding. Guarding the Gaza “perimeter” is prioritized to securitize the borders of Israel for Jewish settlers who moved from the region beyond its walls, as new communities expanded beyond that perimeter, the tunnel systems have grown as an increasingly robust form of hidden governance, hidden from surveillance.

If the network of tunnels first built to smuggle weapons in from Egypt in the 1990s before Israeli troops left, it expanded in depth and sophistication as Hamas gained control over the enclave and as it grew economically isolated, both as a network for importing goods and cross-border attack, extending five times below the depth of tunnels dug at the start of the new millennium, across a network claimed to extend over 500 km by 2021, according to propaganda videos of Yahya Sinwar, the length of the New York Subway, able to reach to Gaza City. If the tunnels dug four to ten meters below ground seemed unstable beneath fifteen feet, the deeper tunnels are harder to sense by radar or to hurt by explosive force, as well as to detect from above ground–some over ten times as deep, if reports of 200 feet deep tunnel structures is true. While the earlier smuggling tunnels of c. 2010 were closer to the surface and far more rudimentary in their framework and structural support–

Palestinian Entering Reconstructed Bombed Smuggling Tunnel from Egypt, near Raffa, 2012/Patrick Bay, AFP

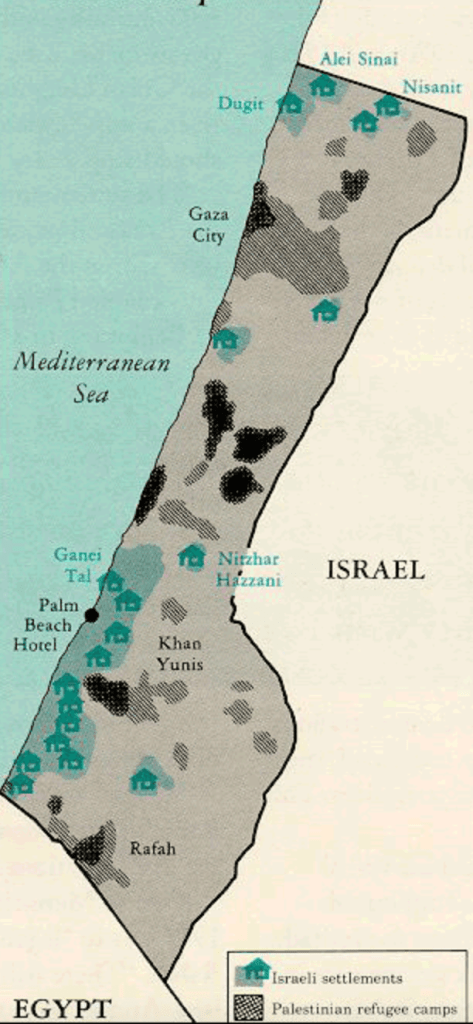

–the robust defensive and offensive functions that evolved of tunnel networks demand more careful discrimination in our maps, and are too often suggested as primitive networks imagined as able to be removed from the Gaza Strip–rather than forms of its current governance. The expertise in tunnel engineering by lego-like concrete blocks, ventilation shafts and soil compacters helped expand the engineering of an underground network tied to Hamas, and increasingly hoped by Israel to be able to be removed form the region, the offensive and defensive network has gained increased resilience. And as Israel’s right-wing government linked itself to the defense of adjacent communities near the wall, and tunnels targeting of Israeli forces or settlements near the border grew in response to a vision of sovereignty that exclusively defined the state for Jewish citizens-settlements mostly made for those Israelis who left the Gaza Strip in 2005, now lived in by a new generation of settlers, familiar with demanding protections for living outside a region composed of refugees before the current refugee crisis created by Israel’s invasion.

Israeli Settlements in the Coastal Regions of the “Gaza Strip” before 2005

Unlike the territory of Gaza or the Gaza Strip that is shown in surface maps of houses, buildings, roads and communities, the underground network of tunnels that extend across the Gaza Strip were long both the de facto network of Hamas sovereignty and the targets of Israeli invasion and air raids. The mapping of the tunnel network has shifted from a target of attack to its re-mapping embodying identification of the tunnel network as the underground nefarious form of negative-sovereignty by which Hamas has defined its presence in the Gaza Strip. The metaphorical mapping of the tunnel network has served to embody an image of the “negative governance” of Gaza, and metaphorically mapped to delegitimize the authority of Hamas as a responsible governing entity.

2. The networks of underground tunnels that grew up to support Gaza’s literally “underground” economy as its borders were closed by Israeli Defense Forces in 2005 became, in 2012 and 2014, the targets of invasion and destruction–as airplanes targeted five hundred tunnels, some of hundred kilometers, as one that running from the South to Gaza City, by bombardment and ground operations–destroying 140 smuggling tunnels that evaded the Gaza blockade, including 66 tunnels used to target Israeli forces. The engineering of tunnels expanded to deeper and broader underground corridors to ferry cars of militants and reinforced by iron, with ventilation for larger mobilization, the network emerged in global consciousness as a new terrain of combat, and a new battleground lying far beneath the ground. Even if North Gaza has, as Israel insists, ceased to be under the sovereignty of Hamas from January 2024, the tunnel network dug beneath the territory has provided the firmest illustration of the survival and resilience of Hamas governance in Gaza.

Israeli Soliders Patrolling Newly Discovered Tunnel at Erez Crossing, December 15 2023/Amir Cohen

Tunnel networks in the Gaza Strip have been long targeted as threats to Israeli sovereignty. From their beginning as cross-border passages designed to import weapons from Egypt into the Gaza Strip, the commercial network that Hamas encouraged since taking charge of the enclave in 2007 for incursion. The networks of underground tunnels that grew up to support Gaza’s literally “underground” economy as its borders were closed by Israeli Defense Forces in 2005 became, in 2012 and 2014, the targets of invasion and destruction–as airplanes targeted five hundred tunnels, some of hundred kilometers, by bombardment and ground operations–to cut the enclave off from external contact, destroying the excavation of 140 smuggling tunnels that evaded the Gaza blockade, including 66 tunnels used to target Israeli forces.

Yet if the underground network that has however grown as a dense network of resistance to Israel’s denial of the sovereign presence Hamas has created deep in the underground tunnels of the Gaza Strip, a difference not shown in many maps of tunnel routes–which show tunnels collectively, akin to surface roads of OSM maps, without distinguishing either the origins, depth, or status as a hidden infrastructure, equipped with electricity, internet access, and communications, that long served as a regional tax franchise. The elision of the different tunnels, and their different quality, flattens the history of the network, and indeeds elide its central importance in Gaza’s governance, by portraying it solely as a target of attack.

Gaza Strip in Maps/BBC/NPR

While these maps are entirely the product of Israeli Defense Forces, they flatten the emergence of the tunnel network, and flatten the entire process of constructing, funding, and using the network of underground tunnels demonized as a target of military attack. Since the rise of cross-border tunnels that have been sanctioned as targeting Israeli forces, contesting the sovereignty of Israeli forces beyond the Green Line, the tunnel network was targeted of a vision of sovereignty that was tied to the invasion of Israel, and increasingly responded to by defined the state of Israel as exclusively for Jewish citizens.

But as the tunnel network has become a target of Israeli attack, it has assumed figural status by cartographic logic both to undermine the symbolic identity of Gaza Strip. It has served to demonize the sovereign claims of Palestinians in the region, and an image of the negative sovereignty by which Hamas has defined its place in the Gaza Strip. To flush that presence from the enclave, or to attempt to remake the enclave separately from the enclave that was attempted to be isolated by the Israeli army as a threat–by a 60 km fence, Egyptian built fence, and patrolled harbor–

–whose destruction has been suffered by the Palestinians increasingly trapped between a map and a hard place indeed, as the specter of tunnel networks has come in a grotesque macabre of Grand Guignol to take precedence over their lives, a spectacle of destruction of homes, intent to define attacks on the neighborhoods of Gaza City by targeting attacks on an elusive underground network of tunnels independent of their habitation or of the cost to civilian lives.

Continue reading