Donald Trump, in eyeing a new term as President, sought to make the global impact that he felt long denied–or robbed–in his first term. His frustration, if in part theatrical and hyperbolic, of the “Russia Hoax” was a deep discontent of being denied legitimacy, and a fear of being condemned to a Presidency with an asterisk beside it, either for having not gained the majority of votes for President, after all, or not winning the “landslide” that he felt a winner deserved. And as the first year of his second Presidency seemed to be gunning for an elusive Nobel Prize by bringing peace to Gaza and Ukraine as if to win legitimacy on a global stage, the image of global dominance–and hemispheric expansion of American power–had deep ties to his interest in the political lineage that was embodied by his one-time backer, and promoter, Elon Musk–who at a critical time was the needed P.T. Barnum to stage the comeback of Trump’s ungainly ride on a Republican Elephant. If Trump helped design the new logo of the GOP as a new circus animal–

–even personalizing it, by 2020, beneath a toupee echoing Donald Trump’s signature hairstyle, as an expression of fealty, the party of politics has become unprecedentedly politicized, all but obviating the need for a convention, as modifications that hairspray imbue the weave with vitality, despite its truly unearthly hue that even hairspray cannot create.

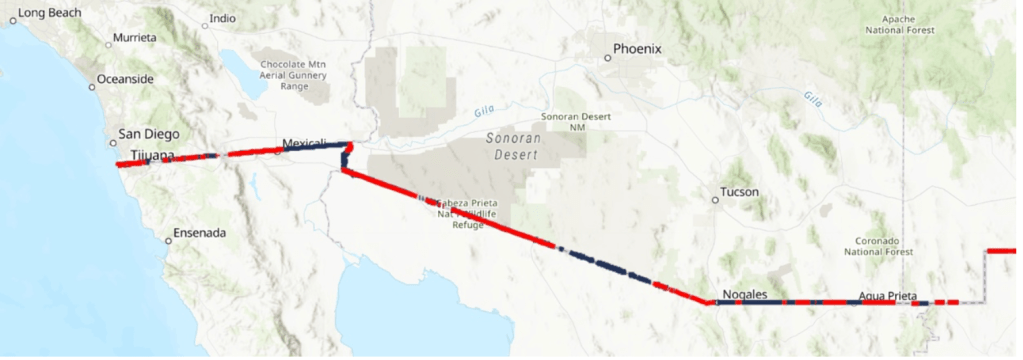

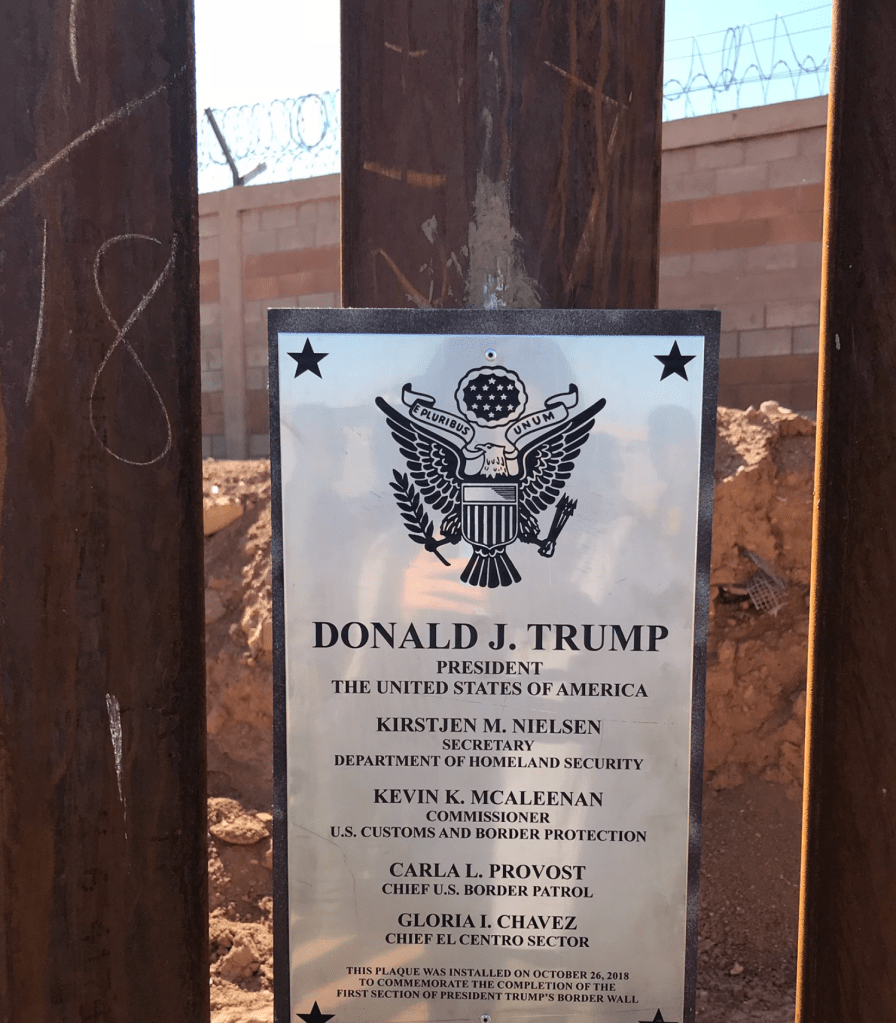

Trump has a dexterity with marketing and branding honed in the real estate business he made his name, and the remaking of the party is in his image is acknowledged in the button. But as much as a rebranding that nods to a fascist legacy in identifying the part with a personal brand, subsuming politics in a lexicon marketing in Trump’s America, the logic of rebranding did not emerge from Trump’s head, like Minerva from the head of Zeus, so much it was a product of the onslaught of rebranding and marketing across America, deeply shaped and inflected by the internet, and online communication, and deeply influenced to synergy with other brands–and possibilities of branding offered by such truly political constructions as a border wall. But the border wall became a subject of the political brand of Trump, the branding of Trump 2 is far more tied to Silicon Valley and Musk if it continues to expand the practice of national politics in ways not rooted in political traditions or the Constitution, and removed form civil law.

Without following legal precedent or legal formulations, the victory of branding the nation has a logic that is almost–and perhaps intentionally–removed from legal remedies or redress. For the logic of the building of a border wall that proceeded only by declaring a ‘border emergency’ and a national emergency became a ‘brand’ far outside of the legal framework of civil rights, and, indeed, flies in the face of civil rights. The brand of the wall by which Trump defined his first term and his candidacy may have had less power by the end of his first term, but the second term must be seen as a terrifying rebranding, and rebranding of America, by the logic of America First, rather than by laws or constitutionality, insisting on values of transparency and economy and an end to abuse–even if the reduction of government costs may mean that seventeen million Americans lose health insurance from Medicaid and the ACA, and reducing the $100 billion the government spent on food stamps and SNAP over ten years will affect the 5.5 million who depend on their food from federal funding in California alone, and leave two million without food. The simulacra of civility that the reductions of federal expenditures are a forced slimming not only of government, but of Americans.

The new branding of America is no longer limited to its borders, or territoriality, but depend on a remapping of an expansive mapping of American authority to use its military in what might be called the vaguest penumbra of actual legitimacy. For the first year of a Presidency has seen apparent expansion of the territorial waters of the nation as borders of military jurisdiction, and a definition not only of the ability to refuse visas to all deemed a potential threat to “Americans,” but to using the military–now understood as a Department of War, and not “of Defense,” in what is hardly only a semantic change or shift. Simultaneous to the unilateral rewriting of the global tariff system, as if arm-wrestling the global encamp, the lifting of protections for offshore drilling, and not only continental water but the nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone, the rebranding of the nation in maps have become unprecedentedly expansive in hopes to maximize the nation’s global impact, that not only flaunt the law, but expand the global footprint, as it were, of America on a global map.

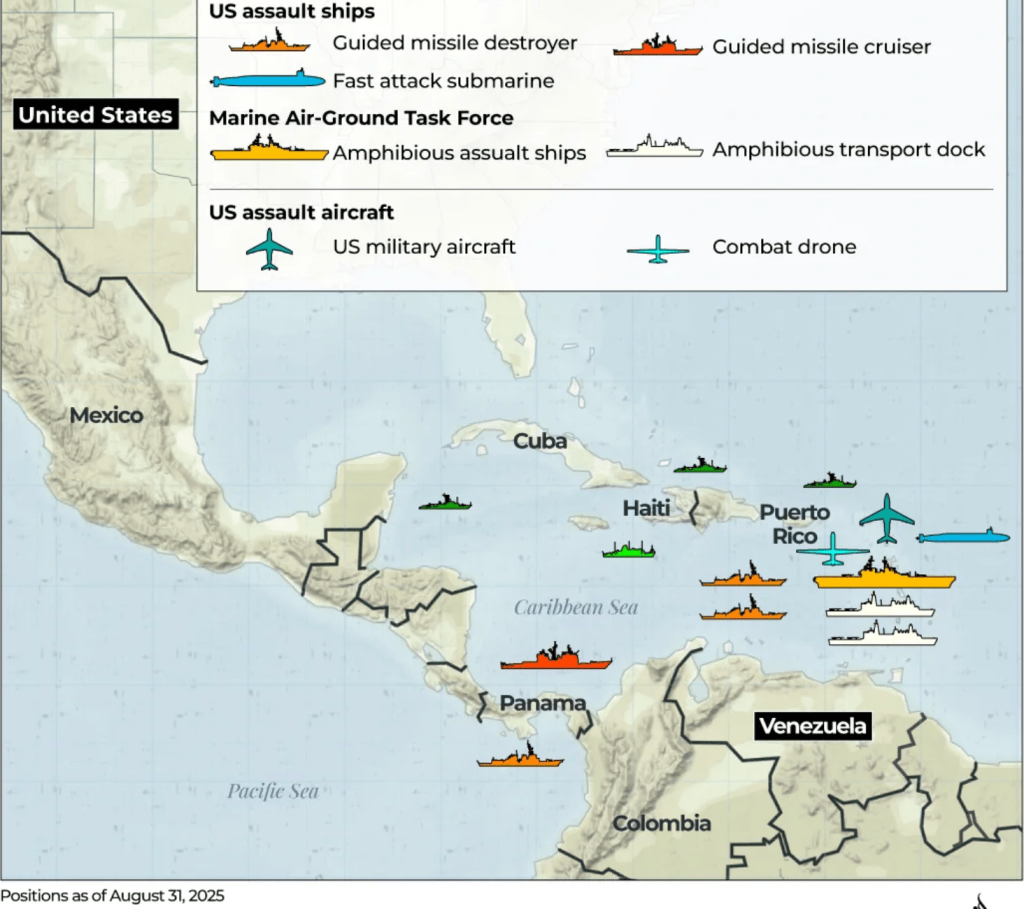

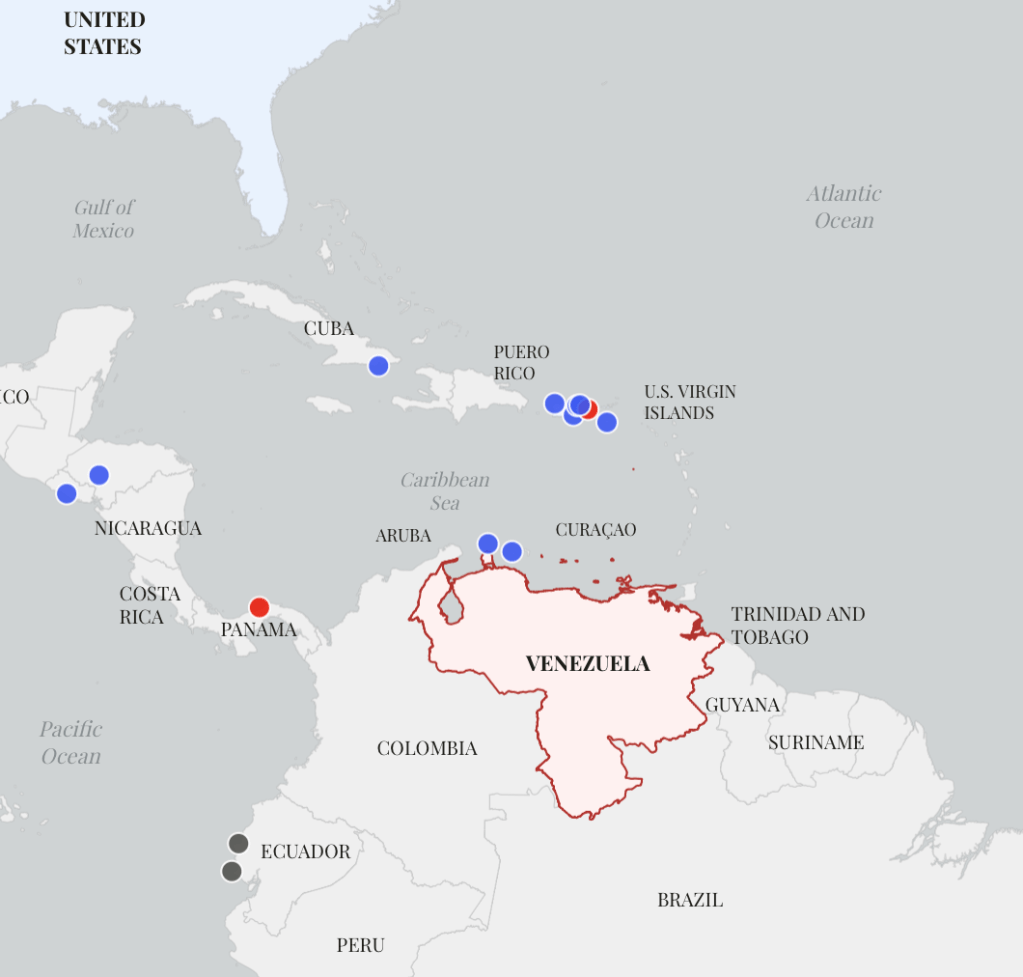

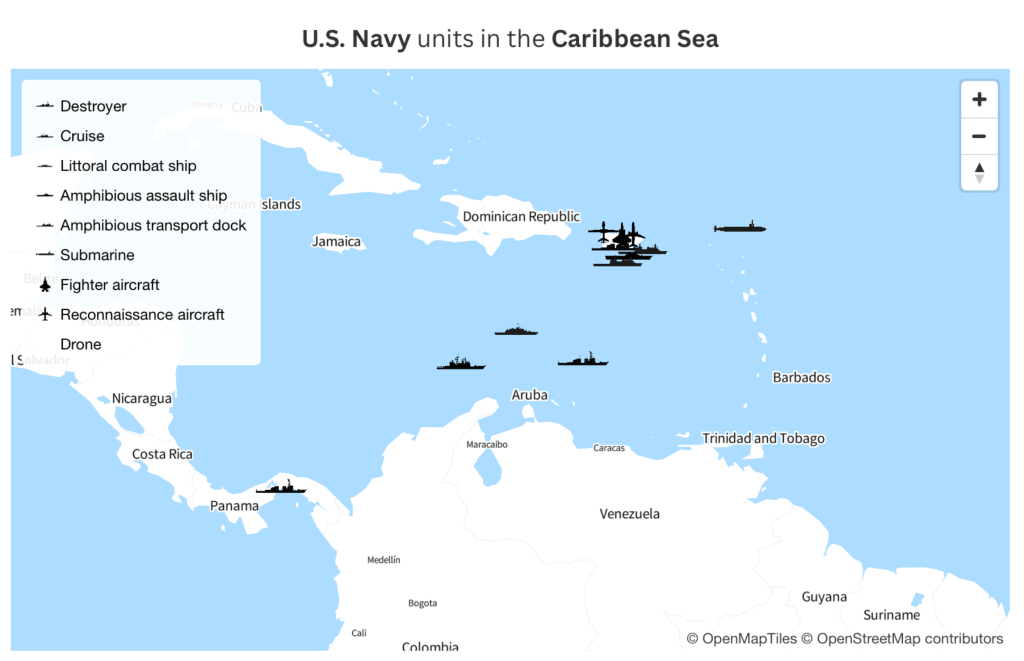

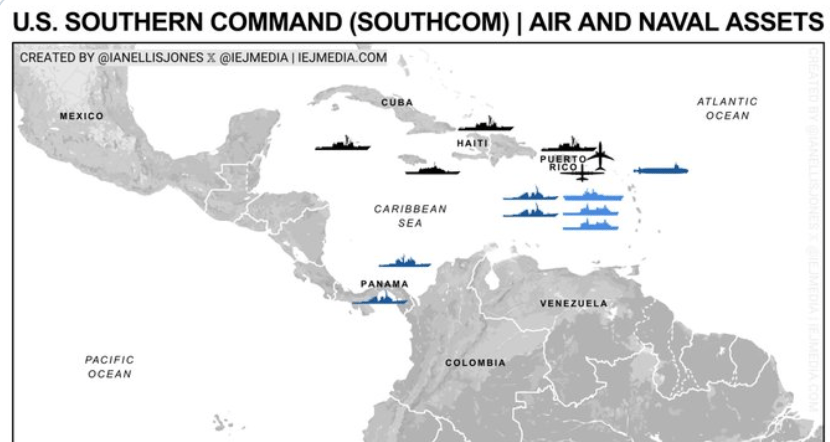

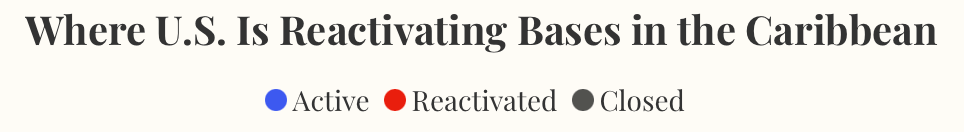

The unprecedented expansion of the War on Drugs to an actual targeting of ships in international waters is not only a metaphor. The new “war,” this time, really is a declaration of military conditions that justify the discarding of international law in the basis of affirming national safety–as made evident in the recent reactivation of a slew of military bases across the Caribbean, to allow expanded bombing of shipping craft deemed a threat to the nation and a national emergency. The notion of a wartime powers that the Presidency has in the past assumed have become a way, at the same time, and with no coincidence, the Department of Defense is renamed the Department of War, to announce a war has been begun that will suspend civil rights and legal accords with nations, or any international body, to affirm the expansive legal domain of the United States over anything it deems a threat to the nation, whether or not such a threat exists. While the expansion of the “War on Drugs” as a metaphor of governance marked a decisive expansion of law-enforcement tactics, prosecution, and incarceration, evoking an “enemy” to be targeted among drug users and sellers, whose only alternative was decriminalization, the metaphor of a strategy of criminal justice has morphed to military policing of the nation’s vulnerable boundaries as if it was a real war understood by national boundaries. What has been treated as a shift of the metaphor to reality as if it were a confusion of categories, however, is in fact a redrawn theater of actual war.

Having renamed the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America with little global pushback, if plenty of raised eyebrows, the recent expansion of targeted bombings on craft accused of ferrying drugs destined for markets of American customers–and cast as the pending incursions by foreign gangs of the nation–have occurred with the reactivation of American bases in the hemisphere, far outside of territorial waters, to a new level of alertness not seen since the Cold War–an amassing of 10,000 troops and expansion of military staging grounds that are intended only to facilitate extrajudicial executions far beyond the line of the border wall on pause since being built in Trump’s first term.

Reactivated American Military Bases in Puerto Rico, Panama, and US Virgin Islands/2025

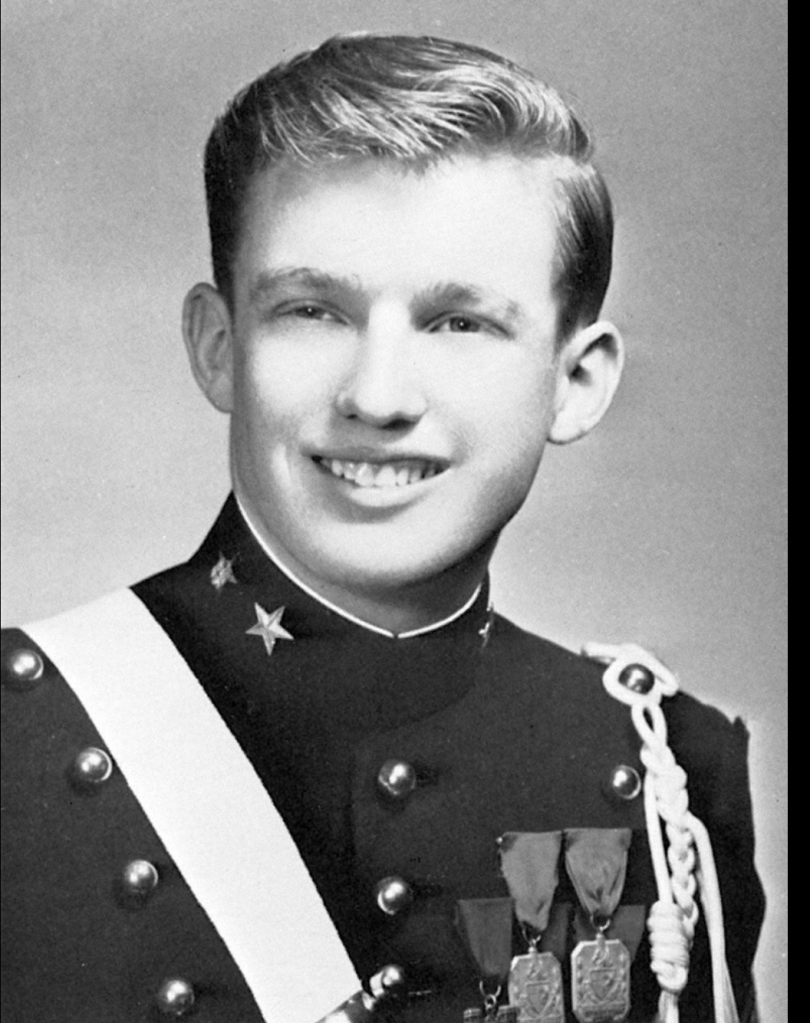

It is as maddening as it is beguiling to map objectively Donald Trump’s relation to the world, so deeply is it performative. It does not objectively exist in ways that could be mapped, trafficking as he does so facilely with fears, existential threats and danger, that conceal a barely credible sense of purchase on reality. Trump’s inflated claims seized willfully and impulsively on maps in his political career, to validate his relatively unclear claims to a sovereign role, eager to try on ideas of sovereignty able to reoccupy the image of his early adoption of the military uniform he wore at the young age, leading a march with pomp and circumstance down Fifth Avenue, fresh from what passed as military training at the New York Military Academy,–anxious to inhabit newfound authority in the Fifth Avenue canyon of New York City–“prime property”–he had never set foot before, as he was trying on a uniform for size in ways that we cannot but associate with the imperial presidency he would later help to design.

Donald J. Trump Leads Military Academy on Columbus Day Parade at Fifth Avenue and 44th October 12, 1963

Fred Trump, no doubt drawing on his own fascist sympathies, had sent the unfortunate future president at age thirteen to learn the needed lessons of domination to reach a level of proficiency to be a capable future head of a real estate firm. But the lesson also gave him a keen sense of entitlement–not having to actually serve in the U.S. Army, increasingly the fear of the men subject to military draft from which Donald sought up to five deferments–and a sense of empowerment not previously encountered in life. The sense that the removed world of wealth was suddenly in reach, and not distant, led him to develop a sense of the synonymity of the Trump name with wealth inequality that helped Donald Trump get in bed with a variety of political forces, gravitating to a dark side of American politics of small government, low taxes, and paleo-conservatism to normalize and perpetuate wealth inequalities in America, at the cost of replacing or eroding government, or what we have come to know as government–and accept as government–without considering the withering away or puncturing of anything that is left of the welfare state or Great Society.

But before he headed to Fordham, and as he tried uneasily to imagine the status a uniform might bring to a child of wealth, the enhancement of his personal authority was but a glimmer to his young eye.

Donald J. Trump in full regalia in New York Military Academy Yearbook (1963)

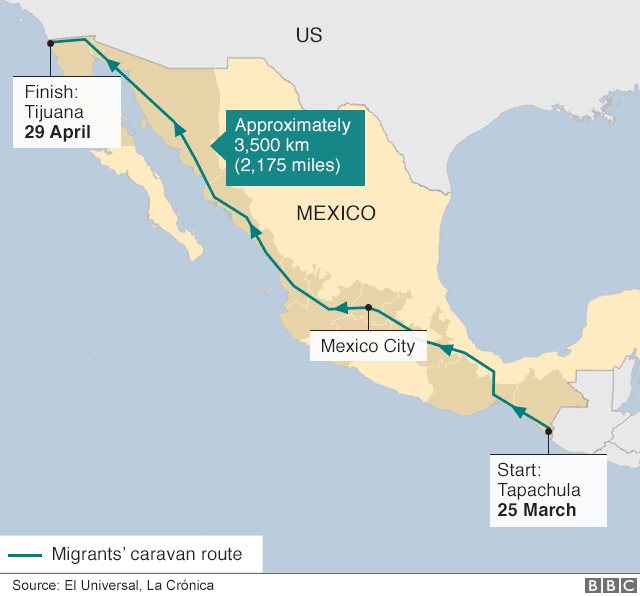

If the frontiers of America have are a consistent theme of Trump’s Presidency–from the bombing of ships in international waters off of Venezuela’s or Colombia’s coasts, ascribed to “narcoterrorists” or “narcotics traffickers” in a “Trump Doctrine” of targeting what “came out of Venezuela” as if it was subject to attack as criminal. The new envelope of legality that Trump has advanced, insisting it not be covered by the War Powers Act and rebuffing international objections from the United Nations, occur under the pretenses that a nation is not being attacked, but criminal organization run by a “designated narcoterrorist organization,” as if this sanctions bombing ships and killing passengers in waters waters lying far outside of American territorial claims. If Rankin and others have suggested that the cartographic artifact of International Waters or an Exclusive Economic Zone can be seen in terms of an optic of globalization, the rejection of globalization or global orders of legal authority are likewise artifacts of globalization–but of the Trumping of globalization that is an assertion of the rejection of legal oversight on attacks of international criminal organizations. The blurring of the nation’s southern border drew condemnation of Caribbean states, claiming wartime powers in a far more open violation of international law than the US-Mexico border wall.

The border wall indeed receded into the baground, fast forgotten in comparison to the extent to which bombing offshore ships blurred the boundaries of territoriality in a misguided attempt to staunch the flow of drugs–a flow Trump and his henchmen too often argued is accomplished by smuggling routes able to be stopped by immigrants, as if this prevented the flow of cocaine, fentanyl and methamphetamines across the border–the blurring of territoriality now goes far beyond the “big stick” of the Monroe Doctrine that the nomenclature of the “Trump Doctrine” echoes, and sets a new standard for a “gunboat diplomacy” now waged from the skies, and from seven warships and aircraft carriers stationed in Caribbean waters by September 1–carrying over 4,500 sailors and marines beyond the nation’s frontiers, in a quite sudden and unexpected military buildup designed to “combat and dismantle drug trafficking organizations, criminal cartels and these foreign terrorist organizations in our hemisphere.” Is the sending warships a new expanse of borders to patrol international waters an act of aggression, or a war against non-state actors?

August 28, 2025

The nation seems to be expanding its frontiers, even as our government shrinks. The wanton summary firing of government employees during the shutdown over which he would preside in 2025, letting go of over 4,100 employees from “Democrat agencies” of government as Housing and Urban Development, Center for Contagious Diseases (shutting its entire Washington office), Education, Treasury (1,400), Interior (1,100), Environmental Protection Agency, and Commerce, and elections security and cyber in an unprecedented unilateral”Reductions in Force” as the shutdown was in its tenth day was a supreme act of plenipotentiary powers, as his Budget Director released “RIFs” in place of pink-slips, purging the note of government by massive layoffs (firings) in classic Trump style for big corporations and budget hawks. What might reduce our emergency preparedness on multiple fronts was conducted in the name of emergency cost-cutting. “March on, Dombrowski, lead the way! Our Poland has not yet perished, nor shall she ever die!” The expanding frontiers of the nation, as government sent guided-missile cruiser, an amphibious assault group, nuclear-powered fast-attack nuclear submarines with 5,000 sailors and Marines to the region–as ten Stealth Fighter F35’s have been shipped to Puerto Rico, supersonic jets of a lethality that has no clear tie to a narcotics war, save as a massive show of force, with eight destroyers.

September 2, 2025

Trump seems determined to send a new sign of his triumphal presence in the region, as if to declare a new relation to the Caribbean as an imperial space he is willing to defend by military roles and military engagement of nations. The metropolitan splendor of the broad streets of the modernist urban grid may have overwhelmed Donald as he stared downthe chasm of an urban canyon whose buildings’ art nouveau facades must have impressed him as a new social geography of which he had not been so keenly aware and a New World. It may have so impressed him as tying the historical figure of Columbus to a conquest of Fifth Avenue,–as a modern Christian soldier–stepping in his patent leather shoes into the future he would argue to have equipped him with “more training militarily than a lot of the guys that go into the military”–a distortion of magical proportions, perhaps born out of guilt for the five deferments obtained to defer service in the Vietnam War, determined to boast of a disciplined leadership without showing much true actual discipline military men are instilled. The determination with which Trump led his New York Military Academy class forward amidst along the glittering concrete neoclassical towers lining Fifth Avenue, as if they constituted a new world he had never personally seen, was a conquest of sorts, a conquest that was Columban in scale and grandeur, as if the commemoration was of his own new role in life.

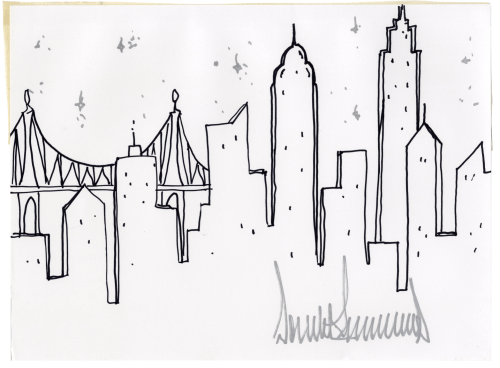

Is this early image not at the heart of his deep ties to the defense of Columbus Day as a national holiday and collective celebration, in the face of reality and claims to the contrary? It is as if predating any sense of global politics, he naturalized the heightened socioeconomic divides of the impressive city. Indeed, the opening up of the landscape would long fascinated him as a developer that he set his sights on conquering this new land of wealth. Those looming towers would be a beacon of sorts for the real estate company he inherited, and provide a soundstage on which his public persona as a realtor could be orchestrated as if existed apart from his father or the rest of his family, and indeed a migration story of sorts from the outer boroughs across the bridge that spans from Brooklyn and Queens to the glittering tower of Manhattan that he traced compulsively on paper napkins as new maps to his identity and brand, even before he took to affixing his name indelibly with their glittering facades.

The new branding of the United States on the global stage is akin to a throwback mapping of a nation’s expansive authority, eerily evident in a favored map that Elon Musk may well have taken out of deep storage in his family memory as he developed plans to help resuscitate Trump’s candidacy in 2024, at a critical time, selling a new vision of the powers of the presidency that seems to have loomed large in Trump’s own struggle for power. Long before applying gold-painted polyurethane appliqué from Home Depot to the Oval Office for a mere $58 to create what he called, a real estate developer at heart, “some of the highest quality 24 Karat Gold ever used in the Oval Office or Cabinet Room of the White House” for “the best Oval Office ever, in terms of success and look” (his string of capitals), perpetuating the image of wealth inequality whose quality would impress “Foreign Leaders” who would “freak out” at its quality.

For Trump ran for President the second time almost under the promise to naturalizewealth divides in a landscape that dazzled him with its display of opulence, as a New World he seemed to have first confronted and remains, for the moment, to be vertiginously in complete command. The deep ties of Trump to a naturalization of wealth divides would lead not only to the demonization of migrants, blacks, and other undesirables, expressing a sense of grievance against them as a real estate developer preoccupied with fears of declining values of their properties,–but to find an eery kinship, at great costs to the nation, with the naturalized wealth divides of apartheid that were a formative part of the worldview of Elon Musk–similarly attracted to the promotion of fool’s gold.

Musk was an icon of the entrepreneurial abilities that seemed to be tied to genius, but was hardly American, and tapped, as has been shown, an eery brand of libertarian politics, not foreign to America, but a dark current that was accessible to the young man who grew up in a white enclave of Pretoria amidst a sense of the deep dangers of those without wealth, amidst the jacarandas and elite schooling, and his heroic grandfather, the dashing adventurer Joshua Haldeman, a refugee of sorts from Canada, who had played an uncelebrated but rather profound part in the social movement Technocracy, whose political imaginary is preserved in the map that is at the header to this post, and received attention as a political imaginary that has informed the apparent contradictions of the expansive isolationism of Trump’s second presidency. The expansion Trump has directed of Homeland Security to apprehend “illegal” migrants is not only an attack on the legal status of refugees–promised safe harbor in the United States and other countries by international accord since 1951 providing that no refugee be expelled or returned to the frontiers of a territory their life or freedom was compromised or in danger. As fears of political persecution have multiplied and the flow of refugees grown globally, the United Nations Convention has been not only questioned–but the safeguarding acquired rights were called into question by declaring the border a ‘state of emergency’ not demanding the following of agreed laws. Indeed, the digital dragnets that are targeting alleged “illegal” migrants compels many to present themselves before court without any right to a lawyer or legal defense, as they have no ability or right to hire one.

Donald Trump had been sent to military academy to dissuade him from a passion for films. Donald was wowed by leading a spectacle that of which he was the center–leading a Columbus Day march!–whose theatrics led him to remember the event. He boasted of being instilled with obedience and rules at the New York Military Academy, endorsing the creation of an online “American Academy” as he ran for U.S. President in 2024 to undermine the place of “radical left accreditors” in American educational institutions and the “left-wing indoctrination” so endemic to schools he argued were “turning our students into communists and terrorists and sympathizers of many, many different dimensions.” Trump was vexed by the protests at universities after his first election, channeling attacks of alt right online journalism as Breitbart News against the universities they argued had become opponents to free speech. Trump adopted a Manichaean grievance of disconcerting alliterative bounce, vowing to “fire the radical left accreditors that have allowed our colleges to become dominated by Marxist maniacs and raving lunatics” as if they had perpetrated a crime against the nation only he, the graduate of a Military Academy, was properly able to solve.

Trump Leading New York Academy on 1963 Columbus Day Parade, to immediate right of Flag Bearer

Trump as he marched down Fifth Avenue must had no sense of a defined a relation to the world–he was seeing New York luxury properties for the first time, but was opening his eyes to the scale of what seemed a global stage as he led the march with utter pride in his uniform and bearing. But President Trump’s conviction he is leading a white nation to an age of plenty, as he led the Columbus Day parade months after I was born, is tragically curtailed in its vision.

In glorying in a nation of closed borders, Trump has clung to a. geographic fantasy and a myth. The scale of global leadership may have long been a problem for Trump to comprehend. But the eagerness with which he entertained and promoted the mythic geographies Trump long trafficked in real estate have sought to promote the nation in a new global context, whose toxic spin is reflected in insistently casting Columbus as a basis for the Christian white foundation of America, embodied in his deep commitment to restoring prominence to a holiday named after the Italian Christopher Columbus. Even as we have documented and uncovered the scale violence Columbus and his sailors perpetrated in taking possession of Santo Domingo, the whitewashed elevation of Columbus as a, a founder of the nation if not of Christian Empire, with deep roots in the nineteenth century at great cost tot a nation. Even as Trump vouches opposing the “woke” change of critiquing Columbus as a figure of veneration, one who “all of the Italians love him so much,” Trump courted white supremacy by Columbus; he embraced a vision of imperial supremacy that animated a proposed monument to Columbus for New York Harbor of bronze kitsch designed by Georgian monumental sculptor Zurab Tsereteli,–in an effort to promote and re-imagine Columbus as a father to the Country, akin to Peter the Great in 1997, whose statuary Tsereteli had previously designed on the banks of the Moskva River to celebrate three hundredth anniversary of the Russian Navy in the very same year.

Zurab Tsereteli, Columbus Monument first proposed offshore Trump Properties on the Hudson River

Tsereteli specialized in designing monuments, and the patriotic monument of grandiose statuary was underwritten by Russian funds as a free “gift” in 1997, in a stunning three hundred feet of kitsch to rival the Statue of Liberty in a foray into American politics. The monstrous kitsch statue of an apparently impassive navigator may have been in the back of his head as he appropriated government funds to reconstruct Columbus statues as his final act as President in 2020, seeking to leave his imprint on a society that had refused to commemorate Columbus as a savior to the nation.

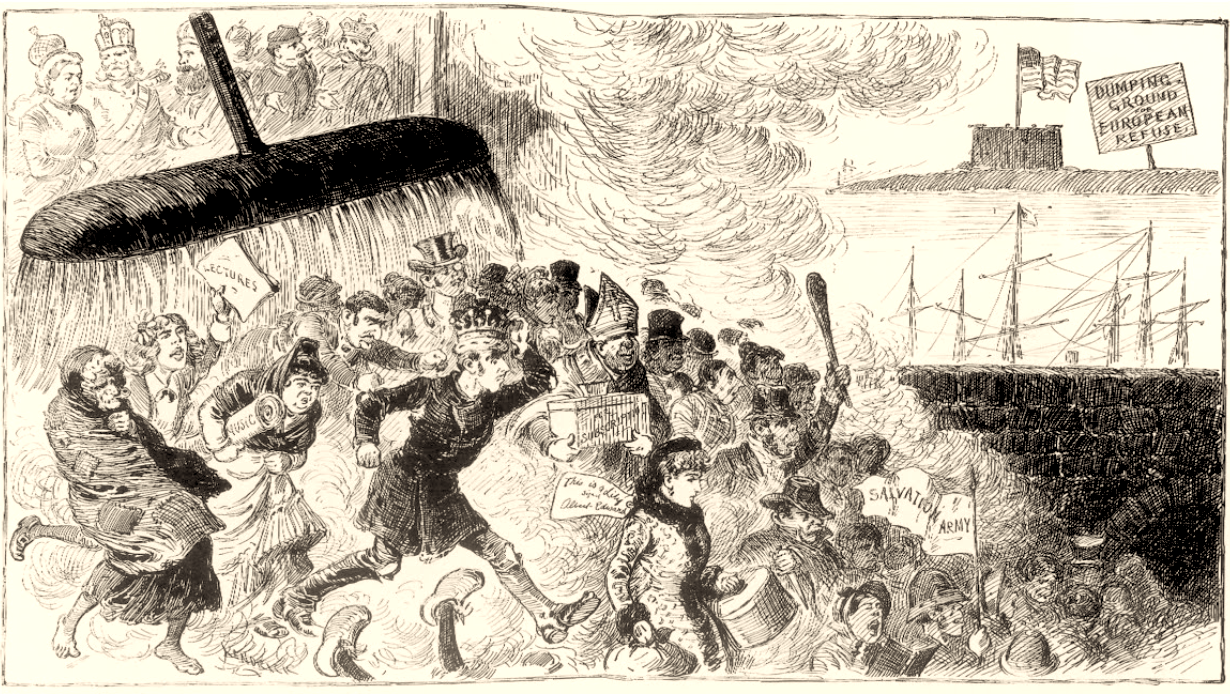

Trump has perpetuated the grotesque myth of living in a prosperous nation within closed borders, as if the arrival of Columbus was triumphant and peaceful–not acknowledging indigenous peoples, slavery, or even non-white history, even in the face of historical evidence of the enslavement and violence that followed the disembarking of European settlers to the contrary. The massive whitewashing of the historical record pandering to visions of white supremacy redefined America in a globalized world as provincial and out of his league as that young costumed military school brat, marching in pants too short and outsized cap shortly before the American troops would be sent in escalating numbers to Vietnam. To be sure, Trump feigned his “military experience” as a doge for five successive draft deferments from military service. Elevating the Christian heritage of America Columbus has come to incarnate romanticized America in a global map of the powerful that Donald Trump could get behind. Yet the uneven distributions of global wealth–far greater than were defined by New York in the 1980s–offered by 2024 a vision Trump’s candidacy seemed ready to naturalize–offering Trump a means to orient his sense of politics to the world. claiming as President to bring “back from the ashes” the celebration of the Genoese navigator’s voyage, and end celebration of Indigenous People’s Day, by renaming the Federal Holiday. The new vision of global prominence for the nation that Trump promised was not dependent on or tied to Columbus, but to a vision of global economic dominance not only rooted but trafficked in myth.

Trump did so, this post imagines, side by side the other spokesperson of wealth inequality who offered a critical endorsement of the candidate in 2024–the South-African born Elon Musk–with world-changing consequences. Musk, like Trump, while super wealthy, also saw himself as an outsider, but claimed a persuasive way to orient Trump 2024 to the world, if not to orient the second Trump Presidency to a map that preserved the wealth inequality incarnated in the buildings and skyscrapers of Fifth Avenue within an increasingly globalized world, perpetuating the illusion of the wealth of the United States by whatever legal fiction possible to provide a vision of American pre-eminence that has some surprisingly scary echoes to the cartographic fiction Elon treasured from his father-in-law, and perhaps the largest paternal figure of his childhood, Joshua Haldeman, a chiropractor from Saskatchewan who accumulated wealth from ruby mines in Tanzania during Apartheid but ended his life piloting airplanes convinced of the hidden riches of the sandy savannah of the Kalahari Desert–not its actual resources of diamonds or uranium, even if it possesses one of the largest diamond mines in the world, but the ancient wonders of the Zambezi Basin of the Lost City of the Kalahari–an obsession of late nineteenth century geography that has survived in board games–of a lost pre-Ice Age civilization only officially given up on in 1964, but incarnated a vision of wealth inequality the likes of which rarely existed before globalization.

Lost City of Kalahari (Late Nineteenth Century and Modern Reconstructions)

The visions of wealth inequality by which both Trump and Musk were so attracted and obsessed made them a far less likely pair to endorse the divides of income inequality that have increasingly defined the United States and the world by the twenty-first century, but which we have been almost unable to glimpse. The manner in which Trump has shifted attention from income inequality to spectacles of state, indeed, is a critical means by which we have allowed our attention to be distracted by the policing of a southern border, but to turn the other eye to urban poverty and the social fissures exposed temporarily in the pandemic, but that exist in both health care, educational attainment, and life expectancies across America, in ways we have hardly seemed able to process.

Kendrick, “And We Open Our Arms to Them”

Kendrick, “And We Open Our Arms to Them”  ICE Arrests of undocumented immigrants, 2014

ICE Arrests of undocumented immigrants, 2014