If unprecedent increased levels of cronyism, corruption, clientism and graft in Trump’s Presidency are traced to the robber barons of the nineteenth century, and gildied age as an era elites controlled without government oversight, it is far more helpful to tie the absence of norms to the corruption endemic in Russia long before 2015. For as the rise of Vladimir Putin to power 2000 marked a license in bribery, extortion, and outright misuse of funds, unprecedented in the former Soviet Union, the search for a sense of stability in the destabilized USSR led to a search for new icons in the midst of increasingly rampant political corruption and cronyism. The lost story of the iconic production of new figures of Columbus, as if a modern strongman of a new era, were produced in Moscow by the favored sculptor of the city’s Mayor, Zurab Tsereteli, in a massive onslaught of statuary that, if we have perhaps focussed on our homegrown statues of Columbus the white Italian navigator, seemed to as calling cards of a bizarrely evocative authoritarian statuary that replaced the monumental statues of Marx, Stalin, and of course Lenin, stood for a new canon of statuary that might slip under the radar as it was gifted to European capitals, New York, and the United Nations.

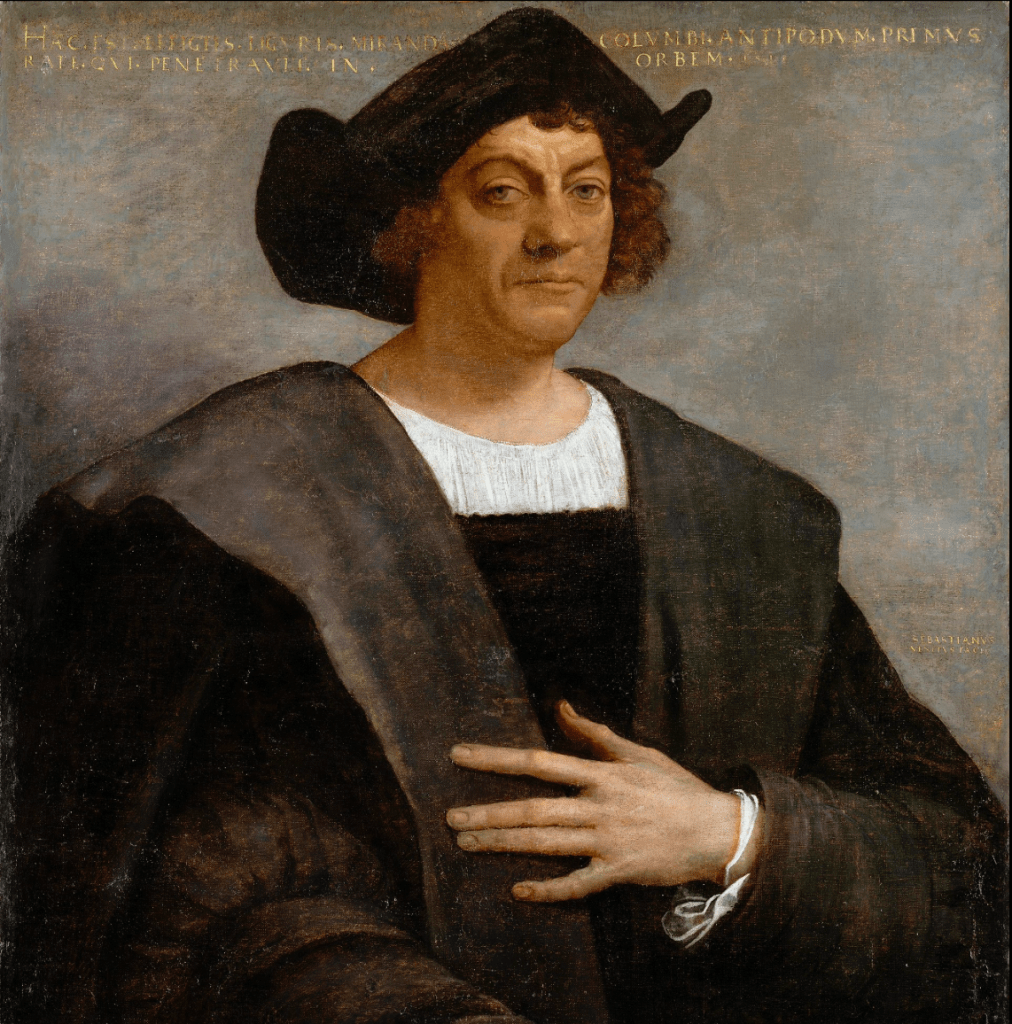

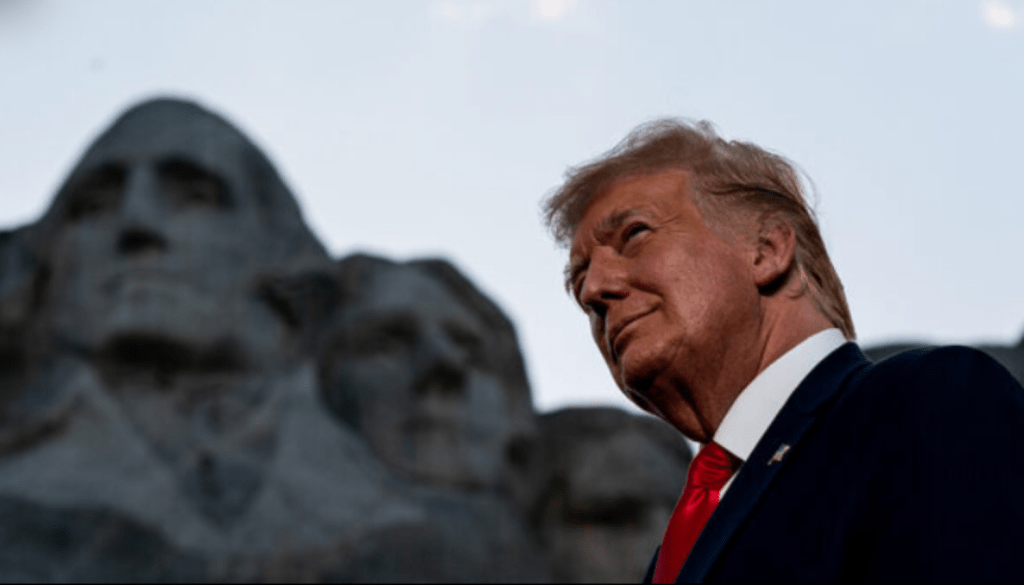

Despite the seeming stability of monumental effigies that command trust, we can trace a search for stability in the inflated sense of self that attracted Donald Trump in this statue of Christopher Columbus as a crusader expansively surveying the Hudson River, shifting Columbus from the site of New World contact he indeed made landfall on October 12, 1492, by remapping that moment as a token of the massive restructuring of global space, and perhaps time, in the ethnically heterogenous melting pot of New York, in what is a precursor and universal model of white supremacy. It is perhaps no secret to readers of this blog that Donald Trump’s first public outing in uniform was on the streets of New York, in a staged Columbus Day parade, just months after my birth, that he commemorated as his first vision of Fifth Avenue property but must have also seen, as a seventeen year old boy, as his first taste of public power, on his own, as he led his regiment down the storied public street where it was no secret he would plant is own flagship hotel. The grainy image of Trump strutting in his costumed finery, Soward in gloved hand, was far from combat, but may have provided the first glimpse of the power of a public parade before an awe-struck urban audience, that made him feel at just age seventeen basking the object of collective attention without ever needing to go to fight in an actual war.

Donald Trump Leading New York Military Academy, Columbus Day Parade, October 1963

If the Columbus Day parade was Trump’s first public outing as a soldier–a new identity he did his best to avoid by delaying his demployment to active duty four times due to education, before going on to receive a fifth medical deferment from Dr. Larry Braunstein–no relation in so far as I know or am aware–five years later from a podiatrist who rented his medical office in Trump’s father’s buildings who held off increasing Dr. Braunstein’s rent, bolstered by the letter of a second podiatrist who won an apartment in another Trump property. By the autumn of 1968, when after having graduated, he won a fifth deferment, Trump looked back on the Columbus Day Parade as a symbol of the extent of his duty, secure that while “I wasn’t going to Vietnam,” he was justified in the sense tat “I was in the military in the true sense,” as if wearing the epaulets on public parade with the New York Military Academy on Columbus Day was particularly memorable, identifying himself proudly with the commemoration of Columbus as if “in the military in the true sense.”

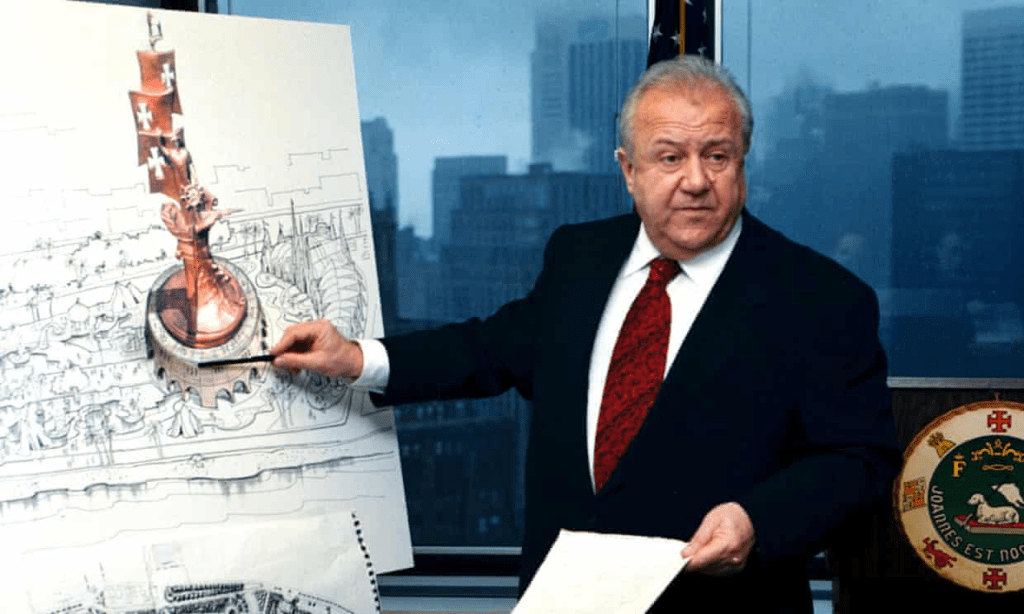

The story of Trump and Columbus. has been understood in terms of his jingoistic patriotism and pro-American claims. But the statue that he helped arrive in lower Manhattan, as if a rebuke to the Statue of Liberty which it would face, eerily parallels Trump’s first entrance into the political stage, as if the negotiation of a possible hotel in Moscow might lead Trump to parlay his popularity among real estate developers to secure a gigantic statue of Columbus for a new riverfront propriety in New York he was developing, seeking to erect the colossal statuary of the Renaissance navigator in the Hudson to prove he was a person of weight–if the statue never arrived on American shores.

The evangelizing statue of Columbus as a Renaissance Man was perhaps in keeping with the 1970s, or even 1980s, but was a massive monument of kitsch. By transposing the taking the site of contact with the New World to stand for the complexities nd the clichés that solidified a confusion of aesthetic and ethical, or elided the ethical, solidifying the romantic image of Columbus as a discoverer that had become an almost empty cliché into what announced itself as a monument of global art whose kitchiness intimates a universal scope anticipates in uncanny ways the universalism has brought to his first and second presidencies. If Trump has been taken as seeking to control the political party, the unitary executive, and the economy and legal norms as President–a vision of supremacy far from the founders–his promotion of this statue of the Genoese navigator who had been claimed as a Founding Father and hero of white supremacy in the nation’s history.

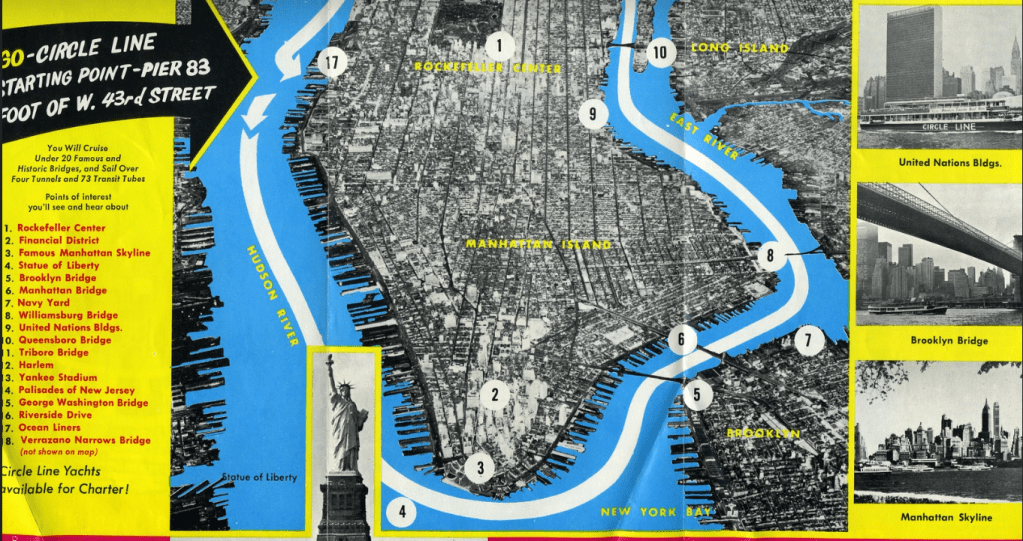

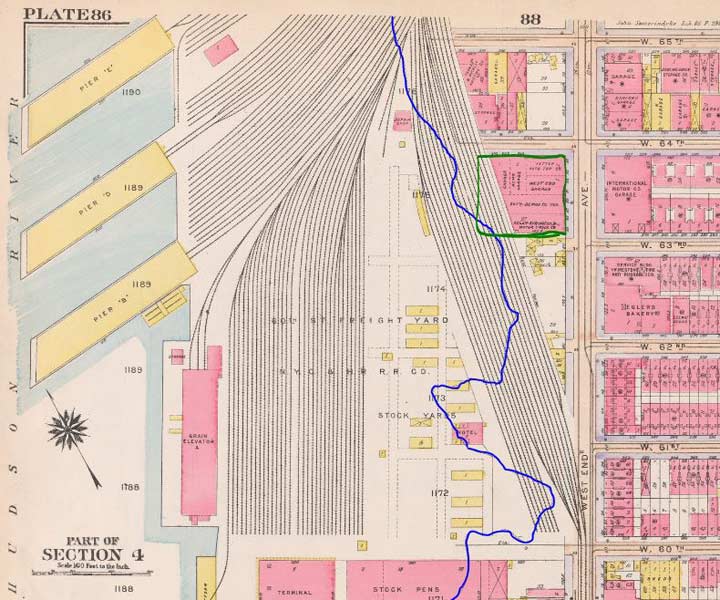

The statue that Donald Trump desperately wanted to rise off the shores of Manhattan island’s west side, in easy visibility of the West Side Drive and just at the start of the Circle Line sightseeing cruise-ship that takes tourists around the island, would be a new symbol of his latest luxury apartment towers, and a vouchsafe of his truly American identity, indeed positioning him, perhaps, as a Presidential candidate and political worth taking note. Perfectly positioned by being situated at the start of the Circle Line–long a serious attraction promoting the city–the monumental statue might take its place in their flyers, beside the Statue of Liberty.

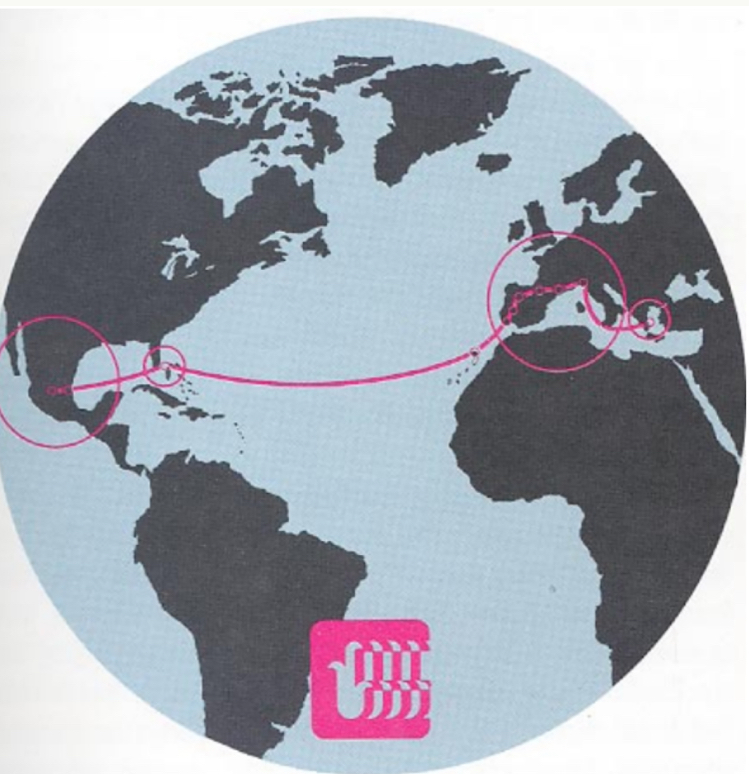

Circle Line Route along Lower Manhattan: Statue of Liberty; United Nations Building; Brooklyn Bridge

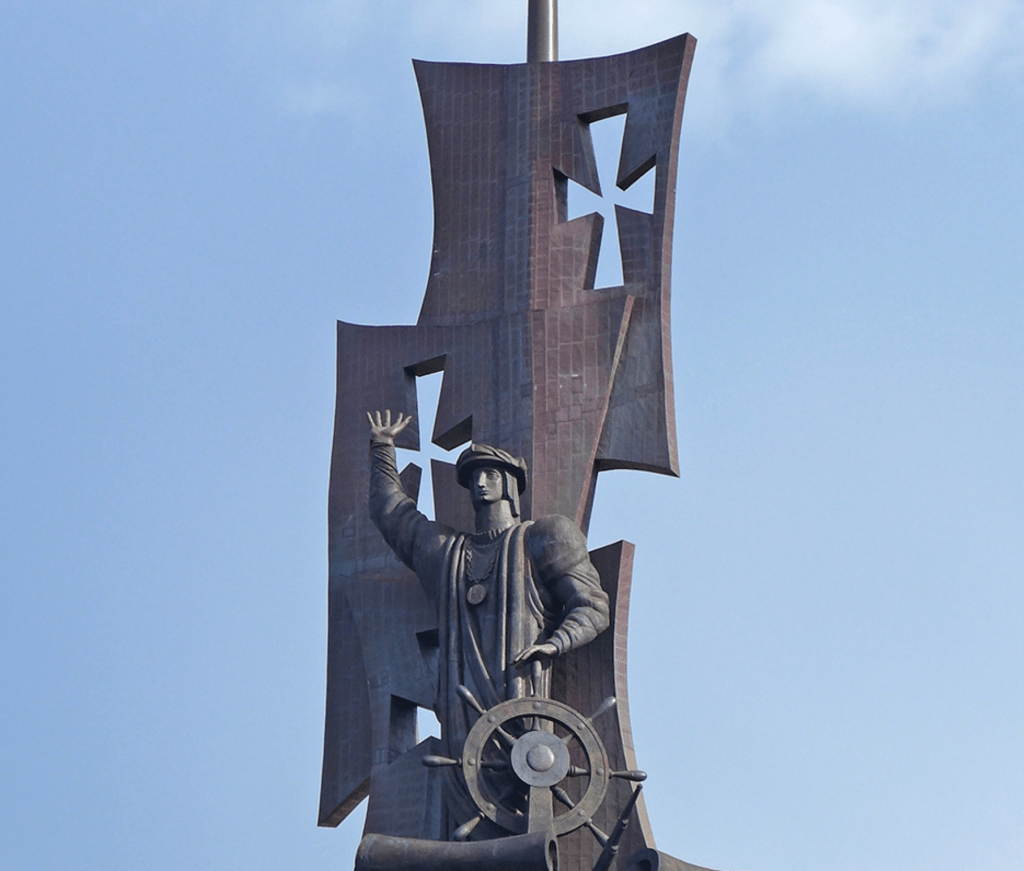

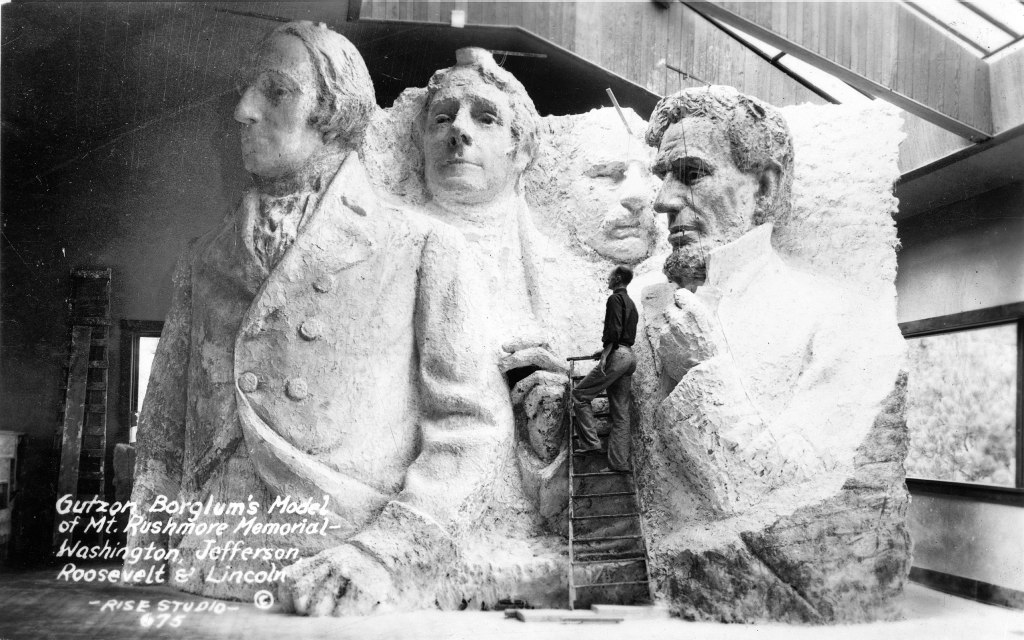

And the manufacture of an icon of stability that demanded attention on a global scale might be traced to the never completed project to construct a monumental 17-ton image of Cristopher Columbus, entitled “Birth of the New World, off the shores of Manhattan in the Hudson River, in a crazy Ponzi scheme to promote Trump’s political entry by the figure of the navigator who had become an accepted icon not only of Italian American identity, but of white nationalism from the late nineteenth century. The hyper-masculine identity of the figure of Columbus as a great discoverer the Georgian-Russian painter, sculptor and architect Zurab Tsereteli had designed already had arrived in 1995 as a gift in Seville’s San Jéronimo Park, emerging from an egg as a fully formed modern man–as if to erase the question of his origin or questions about his heroic intent–holdin a scroll that seems an alternative scriptures to herald the birth of a New World.

Zurab Tsereteli, Nacimiento de un Hombre Nuevo (1999)

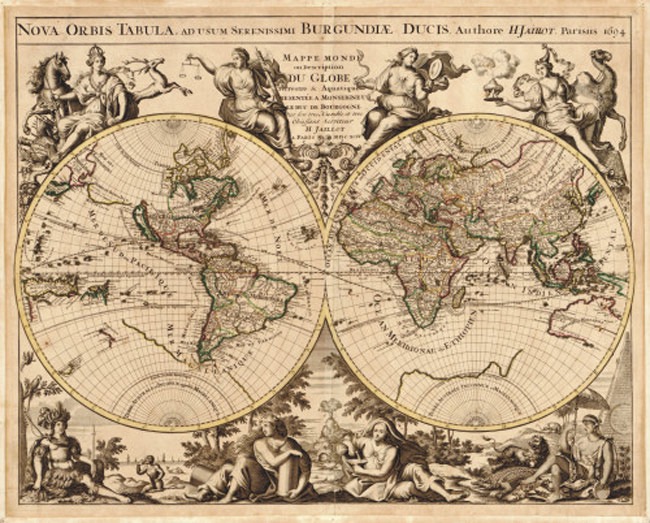

The monumental statue update the iconography of the self-made Renaissance Man. The gift from Russia commemorated the five hundredth anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, using a new artistic repertoire of artistic kitsch to create the largest statue in Spain in order to to commemorate the anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in the Caribbean in 1492, at forty-five meters, but became a target for repeated vandalism and theft of its copper plates, the local government looking the other way at attacks on the pretentious gift of Moscow’s City Council. The triumphal image of the navigator as a robed prophet appeared in a new authoritarian guise, more in keeping with the twentieth than fifteenth century, despite the austerity of the robes by which he was draped. The statue looking out over the Atlantic Ocean, as if he already spied the island of Hispaniola, stably standing on the shore of Seville, a Man of the New World,–in a symbolic rebuttal of the new recognition that was won of the emergent role of Mexico and of Central America in the ceremonial route by which a woman runner carried the Olympic flame from Athens the navigator’s home in Genova to Mexico City in 1968, in symbolic recognition of the emergence of anew world order in hope to inaugurate a truly universal global playing field.

The Route of Caryring the Torch from Athens vis Genoa to Mexico City for the 1968 Olympics

The conscious attempt to echo the path of the Genoese navigator by stopping at Hispaniola before entering Mexico and crossing land to Mexico City was meant to signify and celebrate the potential investment of the large metropolitan center as the focus of the global games, and international recognition of the recognition of Mexico’s national modernity, even if the festivities were to be marred, in historical memory, by the demands for more democratic government of students, and response of the violently repressive Tlatelolco massacre–and the protests in a final ceremony remembered by the internationally broadcast fists raised in a black power salute of American runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos, an iconic contestation of racial oppression that undermined the carefully stagecraft of promoting the arrival of a Mexican Miracle.

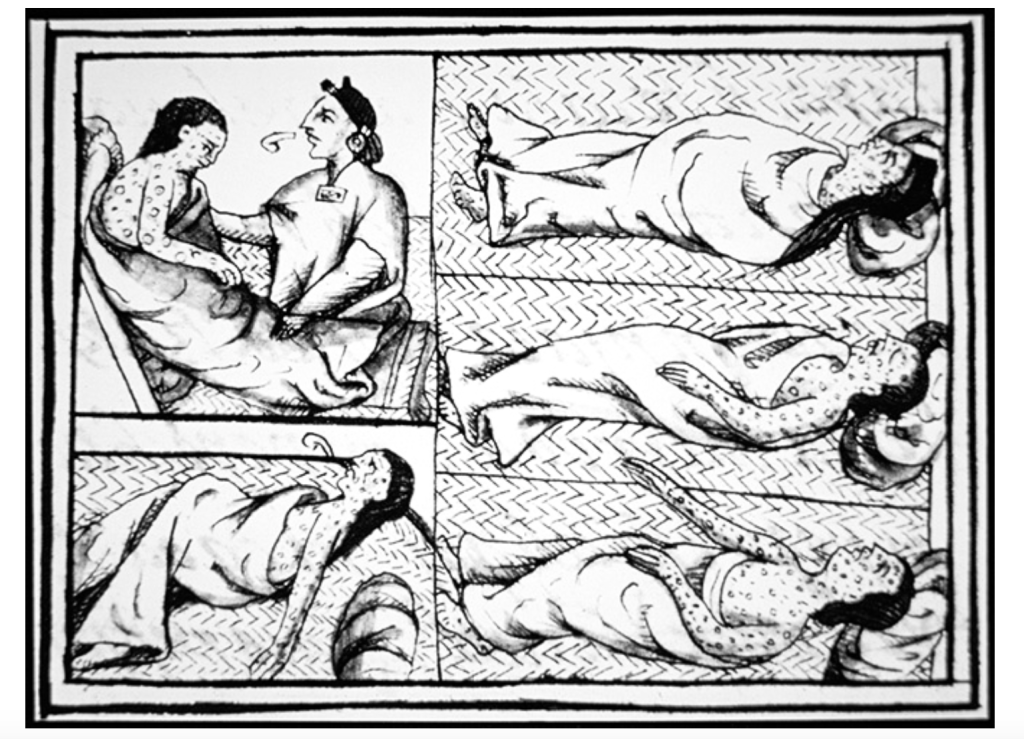

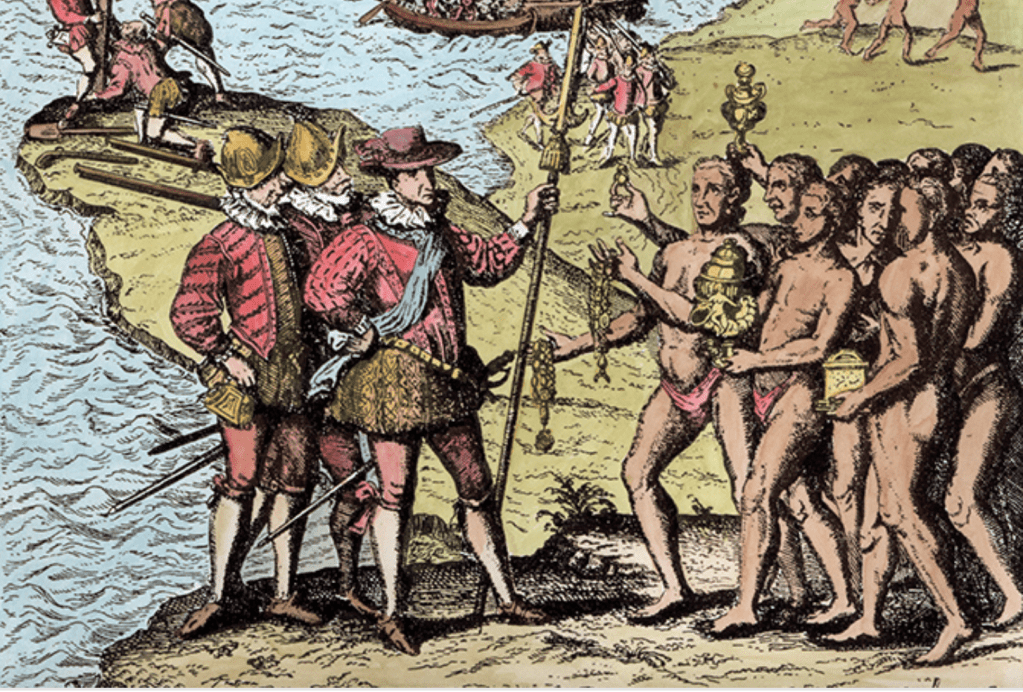

The new white supremacist President was a throwback, of course, who had claimed Columbus as part of a white supremacist pantheon. Donald Trump would of course use the White House as a backdrop to accept the Republican Party’s nomination as candidate in 2020, he noted that the seat of executive power “has been the home of larger-than-life figures like Teddy Roosevelt and Andrew Jackson, who rallied Americans to bold visions of a bigger and brighter future,” revealing unprecedented aspirations to monumentality. They seem little changed, in a sense, from the use of Trump Tower as a backdrop to present himself as a political candidate in 2016 and for his decision to enter political life. (Trump in 1990 confessed Trump Tower was a critical “prop” to continue the show that was Donald Trump to sold-out performances; in 2016 he used the border wall was the prop to claim and magnify Presidential authority.). The Russian production of these monumental figures of a heroic navigator were however the creation of a new global canvas, or the promoting of a new globalism–the robed navigator became recast in monumental terms he had never been seen, as an authoritarian figure, erasing the fact that he brought enslavement and diseases (smallpox, typhus, measles, influenza and more–a new range of bodily symptoms indigenous healers were stumped as they had never seen or developed adequate responses–

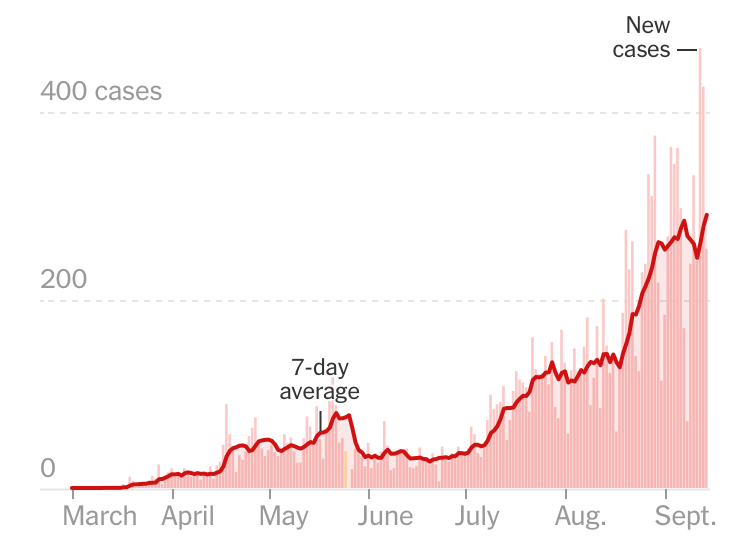

–before which they were as powerless as the the current spate inoculations we receive each winter remind us still survive–and we may soon be as susceptible, if anti-Vaxxers prevail. The diseases nearly extinguished a foreign civilization, arriving with the pigs in Columbus’ ships rapidly spread a virulent swine flu, reminding us how much globalization is tied to virulent diseases’ spread, beyond questions of economic traffic, and displacement. Yet memory of violent displacement of indigenous was a memory this figure of a monumental Columbus seems determined to seek to erase, preferring to echo the standard images of demonstrations of obeisance and tribute money from natives that became artifacts of the inevitable spread of empire.

The studio of this Russian sculptor become a clearing house for concrete monumental statuary that seemed to advance a new notion of globalization of smoothing over edges and naturalizing wealth inequality. The ungainly heroic statue the same Russian sculptor designed of the Genoese navigator that Donald Trump hoped to bring to New York to survey the Hudson River only found its home as a tourist attractions when the tallest sculpture in the western hemisphere was constructed in 2016, the year of Trump’s own first inauguration as U.S. President, in Puerto Rico, the only part of lands in American jurisdiction to accept this freighted totem of political theater and monumental folly. Despite the failed petition of the Taíno people to have the triumphal statue refused as an emblem of genocide, the bronze statue of nearly three hundred feet that had arrived in New York in 1991 has been itself the subject of global migration, the offer rejected from six cities in North America, at the invitation of a local businessman, making landfall far more closer to where Columbus had–where he now waves, in eery abandon, from the shores of an outpost it was finally installed. The bronze assemblage Trump had gushed in 1997 to Mark Singer he was “absolutely favorably disposed,” describing the “great work” of forty million dollars in bronze material alone Moscow’s then-Mayor would “like to make a gift of” was boasted to be the being work of an artist both “major and legit.”

The artistic value of the sculpture can be long debated, but marked a map of the global relations of Europe to the New World by a totemic artifact of a Renaissance Man. It had been decided by the time of Donald Trump’s descent down a gilded escalator to announce his political candidacy in the kitschy atrium of Trump Tower–an event that has already faded in the public memory to the long ago past–to relocate the statue from its prospective site at New York Harbor, beside the landfill properties Trump owned, whose water rights he treated as a potential site for its erection. Was not th garish structure a model for the breaking of aesthetic categories that has become the hallmark and feature of the Trump Presidency, from the redesign of the Rose Garden to the interior of the White House, which seemed increasingly able to be transformed from public property of the nation to a replica of Mar a Lago as if it were the personal property of the occupant of the Oval Office?

The erasure of sovereignty that is marked by the mask of kitsch art that Trump embraces offers a false monumentality that resembles the nation, and national sovereignty, but is only a hollow substitute for a nation or national past. One thinks of the sculpture park that Trump hopes will monumentalize “giants of our past” that Trump has selected–Billy Graham, Whitney Houston, Sam Houston, and Antonin Scalia–are planned as a virtual payback to the nation, and would feature a version of Columbus, in ways that recall the attraction that the monumental brutalist statue of the navigator who has become a target of historical reassessment blamed for the start of the slave trade and extermination of indigenous, as much as a discoverer. If the unexpected Presidential candidacy of Donald Trump reset on the exhortation to remake the nation, a line may be traced for the show Donald Trump to the unethical corruption of Putin’s rise in the appearance that Trump promoted of a rather garish monumental statue of Christopher Columbus he hoped to place in New York harbor, beside his latest planned development, that might someday be recast as a forgotten bid to enter national politics wedded to a quite reactionary vision of the glorification of the navigator as a celebrated hero of America’s past, and a focus on American “greatness” that was rooted in kitsch and on the falsification of a past grandeur of America’s past, a traffic in monuments that Trump seems quite keen on making central to his Presidency and legacy.

The monumental statue that would take a place in the Hudson River as a spectacle of power, able to rival and replace the Statue of Liberty as an icon of masculine strength. Unlike the marble statue of the Genoese navigator given by the recently created Italian government to Philadelphia’s Marconi Square in 1876, positioning Columbus above a world map that foregrounded North American and not the United States, the Renaissance Man on a ship’s deck on its transatlantic voyage was a monument of neofascist kitsch, outside time and space. If Italiy’s government had obligingly presented the marble statue atop a globe tracing North American as if rendering the navigator’s inner mind, in “Anniversary of the Landing of Columbus, October 13, 1492,” as “a tribute from Italy to America” at a time when Italian immigration to America had not yet really spiked, the Russian statue borrowed not from neoclassical statuary or actual likeness, but a brutalism widely mocked. The nineteenth century statue celebrated political independence from a new Republic, independent ffrom its royalist past of the House of Savoy, whose heroic cast reflected aspirations to nationhood in a center of republican reform, within a tradition of artistic portraiture–

–the monument marking a political turning point to the foundation of Italy as a republic America’s political stability during its first century as a republic, a brilliant gift of state returning Columbus’ likeness to the city seen as its first republic of letters in the colonial era.

The marble statue of Caroni has been since removed from public prominence from 2020, at the recommendation of the Philadelphia Historical Society; but the gift from Moscow of a monumental Columbus was less of a gift of friendship or republicanism, than the result of the global exchanges and aspirations for monumental grandeur in a figurative vocabulary that abandoned any trace of realism, historical accuracy or specificity, and as an icon of Christian authority.

The statue that would have arrived in New York Harbor thirty years prior is a model for Trump’s romancing of the monumental, and of his denial of the aesthetic tastes of elite culture or occidental norms of ancient leadership, more resembling the kitsch monumentality of the steel reflections of Trump Tower’s bronzed facade of reflective glass and quite garishly gilded with gold veneer, an architectural travesty to restraint or taste. More explicitly than the kitsch of Trump Tower, since opening as hosing condominiums in 1984, provided a precedent for aspirations to landmark status with its varied reflective surfaces. the Columbus statue planned for the Hudson has not been fully situated in the discursive fields of white nationalism, political statuary, and commemoration that it occupied, or in Trump’s taste for disrupting national standards of aesthetics, pandering to public tastes for grandiosity as much as to national traditions. For the massive rather bizarre statue of the bronze sheets that were sculpted as Christopher Columbus, a triumphal statue rom Russia, devised by Russian patrons, provided an eery precedent for the absenting of history from public space.

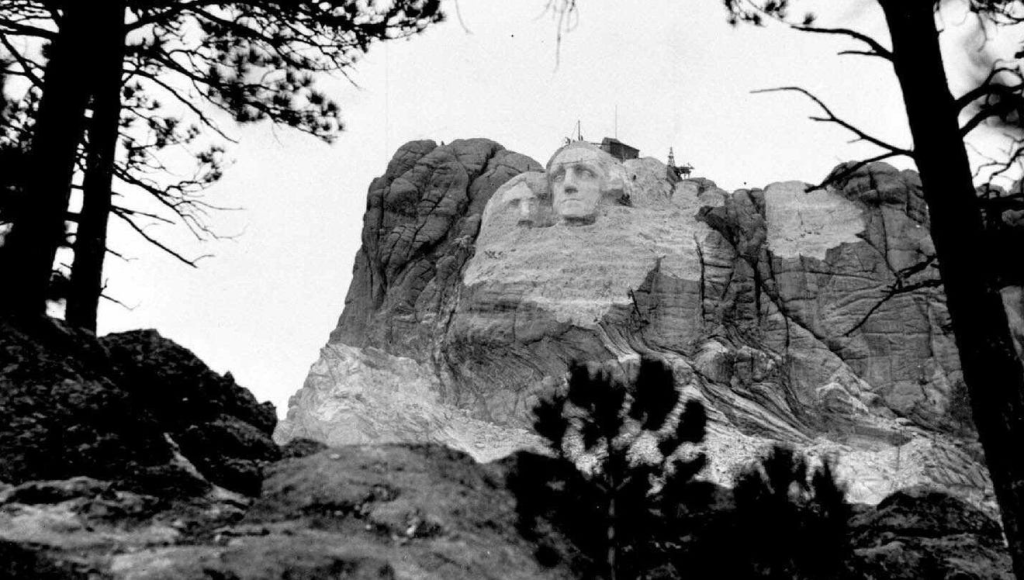

If Trump Tower was an assemblage of luxury elements, the odd anonymous monumentality of Tsereteli’s import refigured Columbus as a triumphant icon by brutalist standards. It was akin to the Truman monument of the border wall, Trump’s appropriation of Mt Rushmore to address the nation on Independence Day, 2020, or the prospect of Garden of Heroes where Columbus joined John Wayne, Confederate Commander Robert E. Lee and Antonin Scalia currently planned to be at last realized during Trump 2.0. The statue informed, I would argue, Trump’s own uncanny sense of staging himself as a President and public figure, and to the optics of elevating lowbrow aesthetics traceable to the bizarre proposal now only a footnote of his career,–that speaks to his long desire to use public art and monumental structures to present himself to the public, and indeed the ways in which other countries have helped provide a monumentalism that spoke to Trump’s enormous need for validating his sense of grandiosity and ego.

It speaks, also, to the origins of an attraction to the transcendent sovereignty of the state, that has increasingly attracted and dazzled Trump, in ways that seem severed from its defense of laws, individual freedoms, or civil society, a sense of a state as disembodied from the ground, and historically transcendent, commanding respect in itself and its inherent authority–a sense that motivated Trump’s repeated directives in Executive Actions Protecting American Monuments, Memorials, and Statues, forbidding the destruction of statues or monuments by “fringe elements”calling “for the destruction of the United States system of government” although those statues are far removed from any action of government or governing.

Trump ostensibly defended “public monuments, memorials, and statues” both in 2020 or 2024, despite his incitement of destruction of the Capitol building in 2021, as a rejection of the “right to damage, deface, or remove any monument by use of force.” The angry righteousness, so difficult to reconcile to actions of January 6 rioters he unconditionally pardoned, directs deep-seated anger toward the “selection of targets reveals a deep ignorance of our history . . . indicative of a desire to indiscriminately destroy anything that honors our past and to erase from the public mind any suggestion that our past may be worth honoring, cherishing, remembering,” vague generalizations, to be sure, that point to the cherishing of a vision of transcendent authority removed from the actual functions of a government or what might be the functions of governmentality. There heroic statue of Columbus–removed to a storage site in June, 2020–closed an epoch whose commemoration may have begun with the statue of Columbus holding the globe aloft outside the Capitol, celebrated as “the great discoverer when he first bounded with ecstasy upon the shore, presenting a hemisphere to the astounded world, with the name ‘America’ inscribed on it“–only removed in 1956 after considerable indigenous protest.

The megalithic status of Columbus of nearly three hundred feet, the tallest statue of Columbus in the world, was unprecedented in size but as a loaded symbol of the nation, dredged from its past. It had been made for shipment to New York City’s Hudson River–a river the historical Columbus never sailed, where Columbus Day has been long celebrated–and was stored for a short time before the United Nations building, but has faded from history since being shipped to Puerto Rico. The statue’s arrival maps onto the disputes about honoring of Columbus in the United States. The legitimacy of the statue that Trump would present to the nation would not be presented to a nation that asked for it, but be presented as a symbol of legitimacy and authority at the same time that the commemoration of Columbus was debated–started in Berkeley, in 1980, before reaching a head in 1992 and when the Columbus and other monuments were covered in red paint in 2019, and the Columbus statue by Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli aimed to commemorate the arrival of the navigator in the western hemispher . The bronze statue of three tons has been effectively deported to Puerto Rico, where Columbus made landfall in his second transatlantic voyage, accepted in 1998 as a gift and potential tourist attraction after it was rejected by six to seven American cities.

Donald Trump’s cultivation of the monumental may have led to a readiness as a candidate for President to seek out the Border Wall as a new national monument. If it is a chicken-and-egg question whether the demand for the wall drove his candidacy or he conjured the spatial imaginary of the wall, the proposal was seized on during the dark years of the Trump presidency as a prop to reveal his commitment to national security far beyond tariffs, trade conventions, and trade wars and revive his presidency or lagging candidacy in what seemed a six year campaign. If the border wall was the marquis event of the Trump Presidency, a site to burnish his legacy and his commitment to ideals, it was by no means the sole prominent he tried to insert in the landscape. But the plans for a statue of Columbus of 300 feet and nearly seven hundred tons in the Hudson River would provide an icon of questionable patriotism.

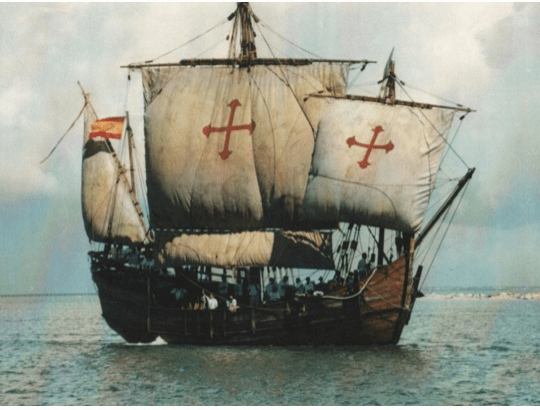

Would it even not launch him into politics, enabled by the mayor Rudolph Giuliani, whose Italian American heritage would help this truly outlandish scheme of transnational commerce? The statue, which seemed to be designed to overshadow the Statue of Liberty, would mar the river, and failed under the ugly pretensions of its anachronistic image of a cubist Columbus behind the wheel of an ship before three billowing sails, although Trump had eagerly promoted the value of an artist he claimed was both “major and legit,” but whose kitchiness was embodied in the truly “prefabricated signs which . . . solidify clichés,” both imitating representational ideas and motifs central to the cubist avant-garde as tired clichés, not to destabilize global categories whose garish triumphalism is a hollow imitation of art. The statue, which narrowly missed being sent to a junk yard, and was long stored in one, borrows from a mythic Christian image of Columbus as a converter of the wild, abstracting his features to tired cubism and abstracting a triumphant arrival to a place he never visited, by a technology of steering the navigator never knew, recycling representational forms in such disarmingly bad taste that they seemed to stage “discovery” as a monumental spectacle that commanded consent. In ways that bid for a taller monument than the kitsch of Trump Tower, after it had opened its doors in 1983, the statue Zurab Tsereteli hoped to place in the Hudson off Trump’s properties by 1992, to tower above Manhattan’s skyline, north of the Statue of Liberty, whose height it surpassed, never actually arrived or made landfall itself. Seemingly designed to be taller than the Statue of Liberty, rather than trampling chains beneath its feet, as that older monument to democracy and abolition gifted by France, the planned statue to Columbus to be gifted by Russia a century later was a universal ideal of the white Christian. As a statement of kitsch, it would complement the condominium skyscraper of Trump Tower as a monument of kitsch, an absolutist vision of sovereignty without historical foundations and dubious ethical or aesthetic value.

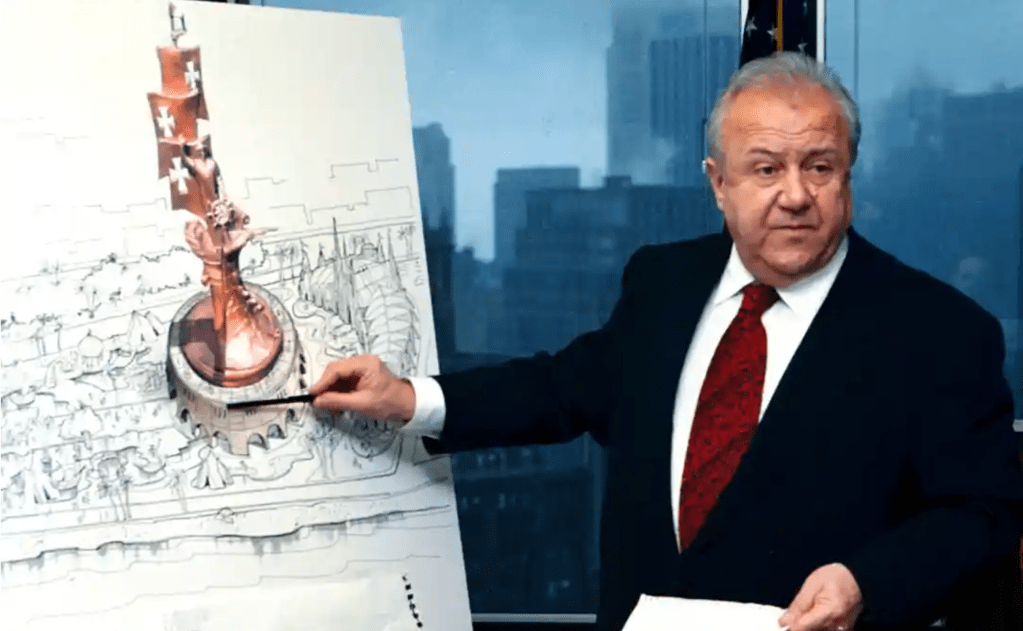

Tsereteli, Discovery of the New World (1991)

Tsereteli’s massive monumental statue was an image of sovereignty and authority, removed from the state and able to circulate globally, unrooted in place or space. Having completed a massive statue for the United Nations, Good versus Evil (1990), Tsereteli was a darling of the Russian establishment, and had proposed global statues in St. Petersburg and many former Soviet satellites, as well as aspired to global renown himself as well as in the United Nations and later in Seville. The three-hundred and sixty foot statue that would be the tallest in the western hemisphere aspired to consolidate and affirm he sculptor’s own renown on a global stage held special significance for Trump as a new stage of monumentalism and of kitsch, and indeed might be examined as a confusion of ethics and aesthetics that marked Trump’s appearance on a global stage beyond Manhattan, and was the fruit of his recent plans to expand real estate empire to Moscow. The arcane financial transactions that led to the monument’s arrival to be proposed to the realtor who had at that point gained only local renown would commemorate the five hundredth anniversary of Columbus’ landfall would have been proposed to several heads of state–including Presidents Bill Clinton and George H. W. Bush–both rejected the monument as a gift of state in 1990, when a prototype of the sculpture in a smaller version was brought to the White House, perhaps seeing little value in celebrating the nation with a gift from a corrupt state–

–the banality of whose openly and unexpressive face is almost explicitly a vessel of the state. The towering monument can be contextualized the new language of statuary monumentality of Moscow, typified by the statue of Peter the Great on the Iakimanka embankment of the Moscow River, recalling the brutalism of Stalinist political culture in New Russian taste, that led to charges of the disfigurement of Moscow by the monuments Tsereteli condemned as “massive and third-rate memorials” of extreme vanity, “truly horrible,” in the words of Boris Yeltsin who visited the statue of Peter the Great that was constructed with the support and endorsement of Moscow’s Mayor, Iurii Luzhkov, who had boldly promoted Tsereteli as a “Michelangelo for our time”–and Trump to to endorse his own sense that “Zurab is a very unusual guy” before local civic groups mobilized in order to tear down the worst statuary Tsereteli had studded the city of such poor aesthetic taste. The sculptor purveyed fantasies of monumentality, and of a rise of global authoritarianism of utmost banality, and tastelessness, appearing to recycle not only his own aesthetic vocabulary but to use formulaic stylistic vocabulary more imitative than pleasing, and indeed only echoing artistic aesthetics. The garish proposal to celebrate Columbus as a state actor and emissary of conversion that is so centrally prominent in Discovery of the New World had, indeed, no audiences but as a tourist attraction in Arecibo, a small fishing community in Puerto Rico, where it was eventually erected, but is a relic of the aspirations to globalism by which we might well understand the political rise of Donald Trump–a politics of symbolism, vulgar aesthetics, and recycled values, generically pleasing or soothing or pleasant in effect, that muted the terror or costs of conquest in a generic monument.

When Donald Trump began to discuss plans to have the towering version of Columbus, looking not different from Peter the Great, Tsereteli had designed several statues for Luzhkov, and the notion of an exchange of favors and ties of the two cities would promote. Trump later returned to the iconic sacralization of the historical image of Columbus as a sovereign emissary arriving smoothly, enthusiastic of his recognition in Moscow as a potential emissary of an image of such monumental kitsch whose ugliness and grotesque monstrosity would be even more strikingly in poor taste than Trump Tower. The statue, that several Presidents had allowed to slip through their hands, had gained significance of a new symbolic level for Trump at a politically contested time, even if he had not yet attempted to enter politics, and served as a sort of visiting card to trump legal precedent, and overturn the disdain that earlier presidents had expressed for the monumental kitsch to which it is safe to say that he was drawn for reasons that joined the ethical and aesthetic, to adopt Hermann Broch, in a statue now known, given the landfall it eventually made in Puerto Rico, in Spanish as Nacimiento del Nuevo Mundo, or more colloquially simply as La Estatua de Colón.

The power of the statue and its persuasive dulling of critical facilities as an aesthetic statement about politics and knowledge, replacing judgment for knowledge, and indeed the aesthetic corruption of historical knowledge that is recast by a recycled repertoire as of seemingly unoffensive politics and aesthetic judgement, blurred ethical and aesthetic questions of building a monument to Columbus by enshrining the public monument in a garish reduction of celebrating Columbus as a discoverer. One’s eyes fall off of its surface, cowed into anticipatory obedience and awe by its size and daring, so that one cannot even bother to frame a coherent aesthetic response from the recycled majesty that it forces on the viewer, clearly intended for mass-viewing rather than for any critical or historically contextual response. The actual accusations of genocide, first formulated in maps and historical revisionism around 1990, and that motivated the reassessment of public statuary of Christopher Columbus in America, fell off the bronze plates of the Tsereteli statue of the navigator-cartographer of Genoa, subsuming ethics to a vague aesthetics of kitsch, in deeply troubling ways to some, but that appealed for their political disengagement and championing of tradition, authority and power to Donald Trump, the realtor-at-large who was considering himself to be untethered from Manhattan or Queens at this stage in life. Santo Domingo and Hispaniola were removed from the land of the Eastern Algonquin Peoples where the river later named the Hudson flowed, an image of the

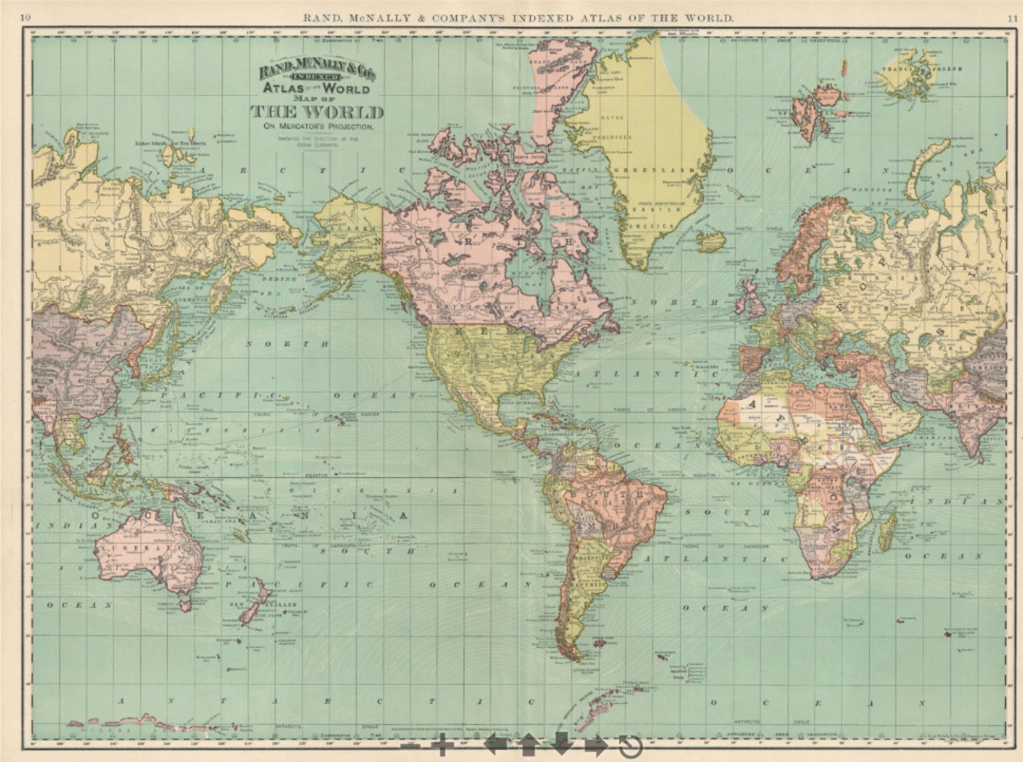

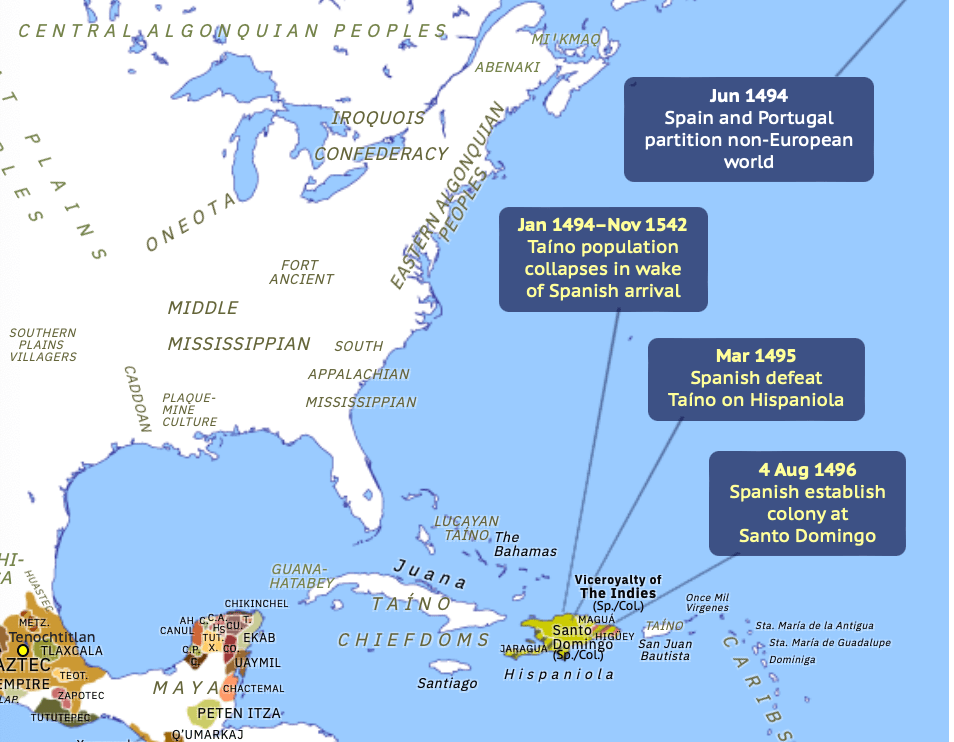

North America and Greater Antilles in 1496/Omni Atlas

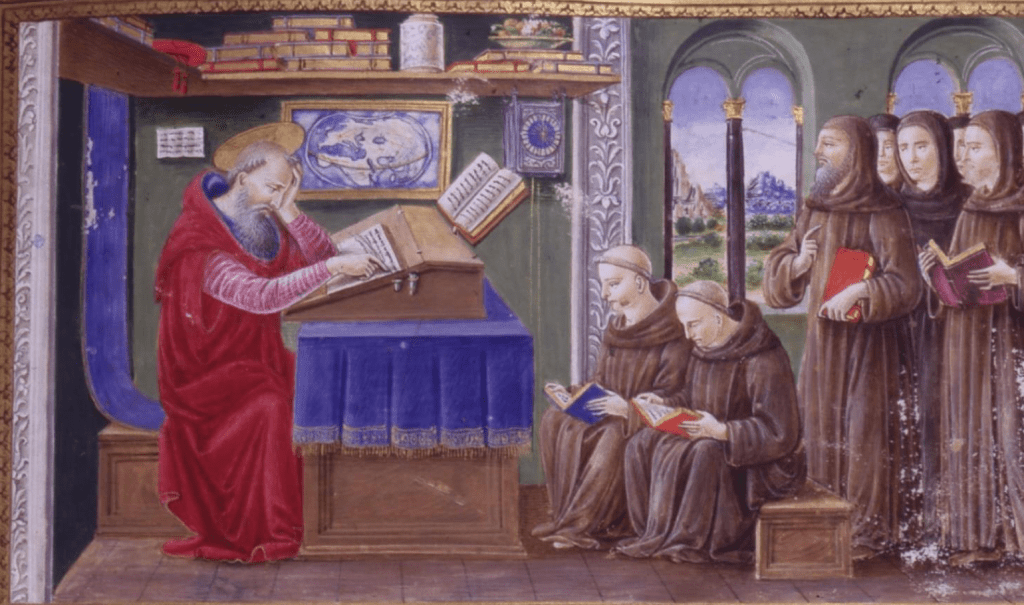

–that revised the image of Columbus as a navigator whose voyages were tied to conversion and the promotion of the Christian religion, celebrated as early as 1497 in a Portuguese Bible made for the Hieronymite monks living outside of Lisbon, by the Florentine illuminator Attivante di Gabriele degli Attavanti (1452-1520/25), whose work, studied by Chet van Duzer, designed the most luxurious of cathedrals’ sacred books as illuminators embellished and tranmitted newly arrived cartographic forms in Florence that made them among the first innovative cartographers.

The inclusion of a map in am image of Paul’s first epistle to the Corinthians, offered a modern-day prospect expanding the Pauline mission of conversion to New World islands–as if the absorption of the global map, even if it only began to include the New World, would serve as a source of meditative focus for the Portuguese priests of Lisbon, secondary to the Bible but sufficiently crucial to their evangelising project to be hung on the walls of a chamber of prayer. Does the illuminated panel not also illustrate the serious work done by the craft of orienting viewers to expanse that is contracted to a monumental statue in the world of the unwanted monuments of cast bronze kitsch?

Lisbon, Arquivos Nacionais da Torre do Tombo, MS 161/7, f. 2r (1497)

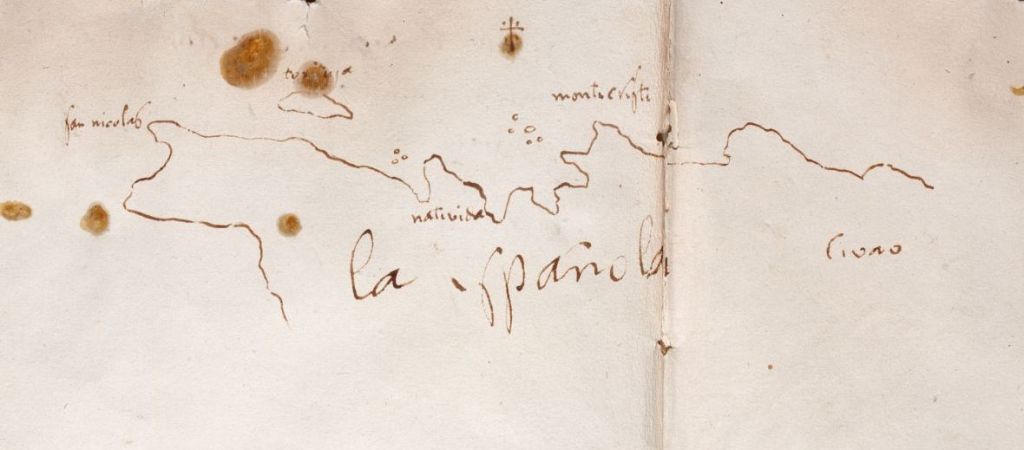

The idealization of smooth mental transit of a course across the Atlantic Ocean is echoed in the elegant New World coastlin in the famous “map of Columbus” that imagined discovery as if a mental act of transatlantic transit, as if announcing entry into a globalized world of no barriers to navigate to Hispaniola’s coast, waiting to be delineated by early explorers. But navigation was only have the process, and rather than a smooth course was anything but a voyage of pure heroism, able to erase the conflict with the land’s inhabitant. The figure of such a victory of transcendence from the terrain was celebrated in the monumental statue as an imaginary expansion of the presence of Columbus in the New World able to be fetishized in the very maps he drew of the New World islands that idealize the moment of contact with a New World as violence-free, celebrating the intellectual triumph of contact at the very moment that they first entered into early modern world maps.

Trump railed, as he would rally against the 1619 project, against the recasting of Columbus as a figure whose arrival at the Taíno Nation on the island of Guanahani in 1492 met the five million inhabitants who inhabited the Greater Antilles before contact, and could be better understood as genocidal after the third day of his encounter, when Columbus confidently predicted showed such ignorance that “they would be all kept in subjugation and forced to do whatever may be wished,” by 1991. The mobilization of such a revisionary assessment of Columbus’ future actions against the Taíno as lying “within the definition of genocide adopted by the United Nations–“acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, an ethnic, racial or religious group”–suggested a fit with the reassessment of Columbus Day and the narrative of colonization by Colon, and an attempt to remediate the “erasure of the Taíno people” that perpetuated the act of colonization Columbus had been the vessel that begun as a crime against humanity and against the environment, a moment of spreading terror by mass enslavement as the emissary of the royal monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, remembered in the works of the conquistador Fra Bartholomé de las Casas. The rejection of Columbus as an imperial agent in Santo Domingo was itself revised, in the championing of Columbus as a kitsch figure within a pantheon of power, transposed to the architectural monuments of New York, and removed from any critical assessment or local contextualization in an early modern map, or from the early modern slave trade that the Columbian voyage anticipated.

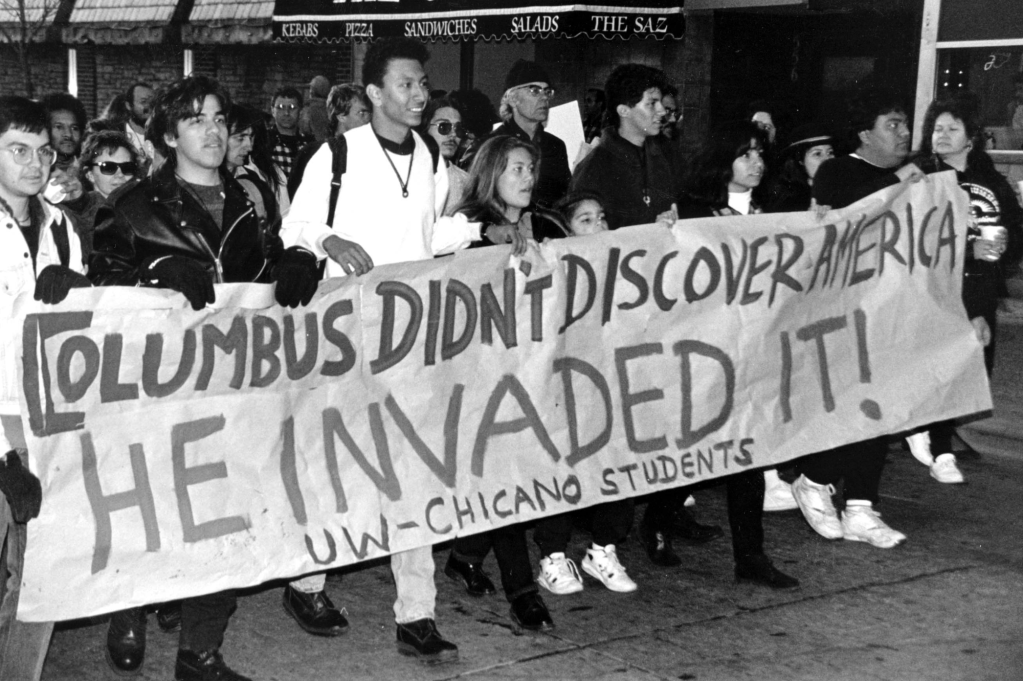

The appeal of the statue’s heroic pose was a tactical move against a broad rejection of Columbus Day, a championing of kitsch over critical contetualiation or ethical evaluation of Eurocentric history, by championing the figure being recast as white colonizer in a heroic tones. By invoking the past icon of Columbus as a Great White Man at the time of the quincentennial, he was lamenting its alteration of received icons of national memory as a bygone day–“Now they want to change—1492, Columbus discovered America”–in ways that provided the seeds of the nostalgia of Make America Great Again. For the time of championing Columbus’ heroism as past had undermined what should be studied in school-–“we grew up, you grew up, we all did, that’s what we learned.“–that make the rejection of the curriculum in the 1619 Project more central as a motivating force to Trump’s politics than the opportunism we often see as its origins. The origins of the reassessment of the 1619 Project were however not rooted in the second millennium, but came on the shoulders of the broad call for curricular reform in the anticipation of the fifth centennial celebrations of Columbus, calls for the reassessment of Columbus’ heroic commemoration culminating in rallies of October 12, 1992, at university campuses as UW-Madison, demanding historical recognition of the context of Columbus less as discoverer than invader, who was a royal emissary of enslavement, destruction, and the bringer of disease and cultural genocide erased in the perpetuation of a cult of his heroism.

October 12, 1992 Protest on State Street by UW-Madison Chicano Students on Columbus Day

The commemoration of Columbus as a modern colossus in the Hudson River was central to the white-washing of history by a massive monument of kitsch, promoting a vision of American history at the core of Trump’s identity, and, paradoxically, the idea of America that Russia had chosen to present to America as a vision of its past. For Trump had promoted as a vision of national identity, adopted from authoritarian oligarchs in Russia and Neo-Stalinist cults of kitsch art, long before he entered politics. Indeed, only the recent contextualization of the disputes on the commemoration of Columbus within the human rights questions generated by America’s role in Latin American politics and an obliviousness toward local human rights in the 1980s and 1990s, blurred over in the enraged crosses stitched on the sails of the ships of Columbus as they arrived in the New World–

–and perpetuated int eh work of Christianization that Fra Bartolomeo de las Casas was also celebrated, casting him as a heroic protector of Mexico, rather than as a Christianizer whose conversion erased earlier cultures, championed by the renaming of October 12 as Indigenous People’s Day at the time of the cleebrataios of the Colombian quincentennial in America, recasting it as a day of reckoning and overdue historical recognition. For the kitsch statue that Trump promoted as a major work of art silenced indignity as it championed Christianity–recycling a range of generic elements of the portraiture of Christian heroism in place of a clear aesthetic vision or political perspective on the judgement of the history of New World discoveries.

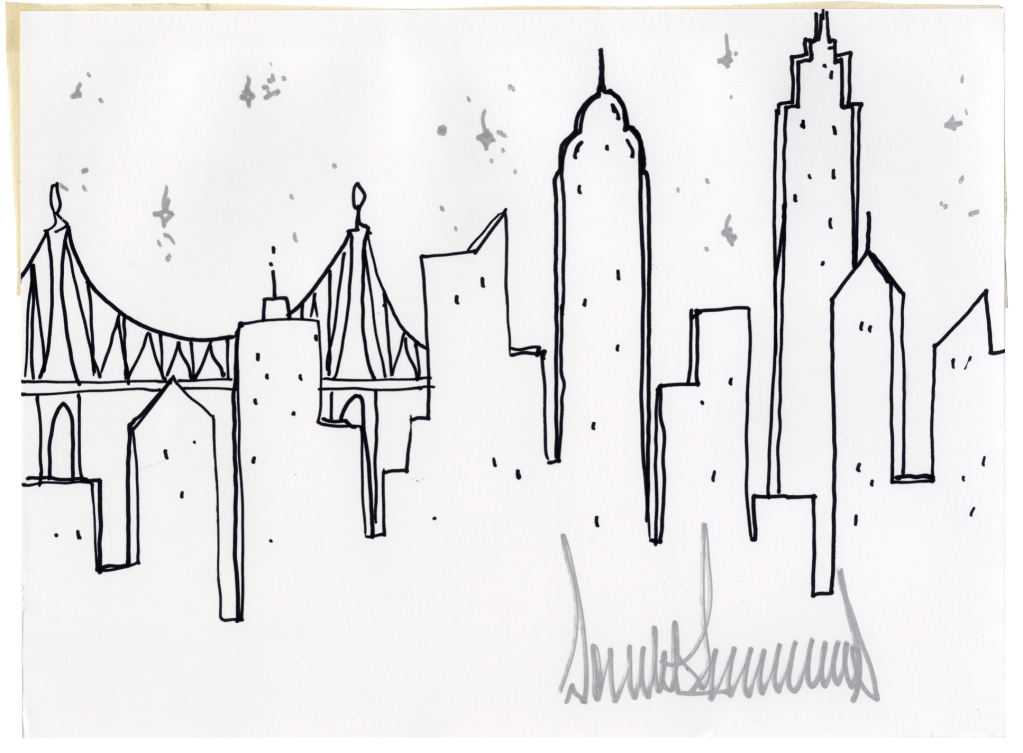

1. For by invoking the monumental stability of Columbus as a historical touchstone during the questioning of the cultural and national iconicity of Columbus as what America would want to represent is central to Trump’s image of his own identity. The singling out of Columbus in an era of genocides so prominent as America approached the quincentenary year of 1992, we get at the heart of what it would be to Make America Great Again. Columbus would alter the Manhattan skyline that is a microcosm of Manhattan, the first theater of Trump’s public fortunes, the case of the towering bronze statue to an imperious Christopher Columbus, that one-time icon of Italian-American identity, already attacked from the early 1990s, when Trump first floated the possibility of its erection on his properties as a gift from the Russian Federation in 1997. The statue that Boris Yeltsin had proposed Bill Clinton accept as a gift for the Columbian quincentennial was seized upon by Trump in the years that he sought to revive his own flagging fortunes in Manhattan as a monument to place his stamp on the urban skyline he identified, frequently tracing on cocktail napkins, with a sharpie, as if he was coveting its gleaming buildings as a young realtor from Queens.

The addition of the planned statue of the Genoese navigator had been routinely rejected as a part of the American imaginary by many groups as early as 1997–the year Honduran indigenous destroyed a statue of Columbus to condemn the project of Spanish colonization, five hundred and five years after the fact, beheading the monument, painting it red to recognize the blood it bore, and throwing it into the ocean, in what had become a ritual desecration of monuments to Columbus since the quincentenary of 1992. The fabrication of the statue in Moscow may have predated the protest movements to remove statues in Britain of Topple the Racists, but reached for a discredited iconography of supremacy at the moment Columbus had been questioned as a figure of American identity–but when Trump felt that he might make a deal for the acceptance of a monument that would appeal to the recently elected Italian American mayor of New York, Rudy Giuliani.

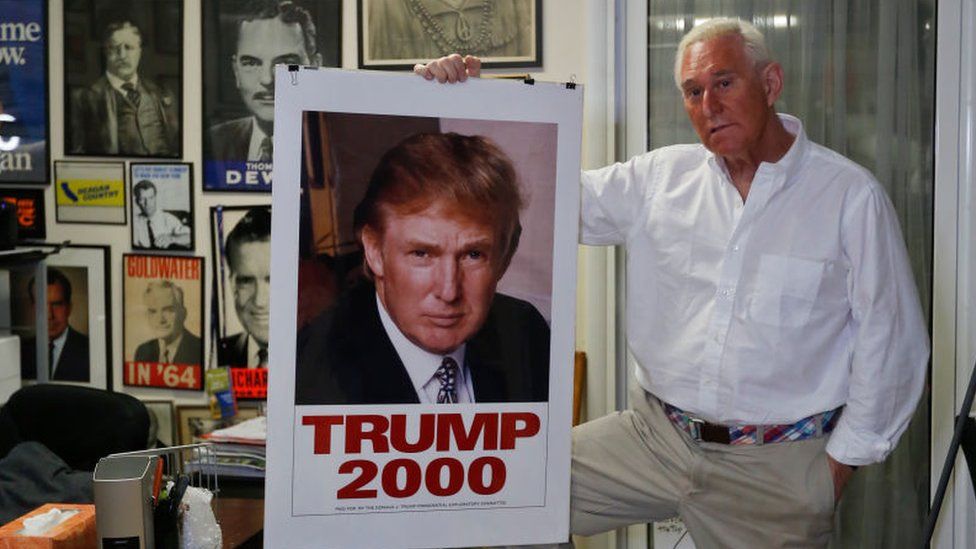

The monument he offered to plant on his properties he was developing on the Hudson River estuary, above Upper New York Bay, near midtown, Harbor, above the Statue of Liberty that rises in the Upper Bay from Beddoes’ Island, would hardly have been precedented for a private residence. But Trump’s sense of combining territoriality of the lands of the old train yards on the expanded west side of Manhattan with a demand for glitz seems to have led him to agree to the deal for erecting a statue, some fifteen feet taller would have provided an improbably gigantic statuary, even if the landfill of his new housing development could probably not sustain its massive weight–yet the image of the massive statue promoting a performative icon of global rule, not long before the first time Roger Stone openly fashioned Donald Trump’s candidacy for President as early as 2000–a poster with uncanny similarity with the official Presidential portrait of 2024. And it is perhaps no coincidence that the occasion for reissuing the executive action protecting statues was, in fact, designed to prepare for the 250th Anniversary of the Nation, in 2026, when the ” National Garden of American Heroes will offer monuments to honor, cherish, and remember “the giants of our past” that might take their model from a commemorative statue that would have arrived to remember the quincentenary of Columbus’ arrival in 1992.

The ill-fated story of the attempted transatlantic voyage of this perversion of a Modern Colossus, a triumphant image of the fifteenth century navigator’s imperious gaze, glorified the imperious form of the navigator without a map or compass, but shows him atop a small caravel, behind three massive billowing flags bearing crosses that concretize his claims to have brought Christianity to the New World, glorifying the man who began the slave trade from the Americas, desperate to turn a profit on his second voyage–who never set foot on the continental United States, let alone approached New York harbor. The imperious view of this statue’s grim visage, an assemblage of sorts, first designed to celebrate the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ expedition made out of 2,500 pieces of bronze and steel manufactured in Russia, cast in 3 different foundries, was assembled in 2016, just after Trump’s election, some 25 years after its first conception, but at a towering two hundred and sixty-eight feet would tower over the sixty meter iron column on which Columbus stood in Barcelona, erected for the 1888 University Exposition, shortly after the Statue of Liberty arrived in New York Harbor in 1885, or the seventy-six foot column on which Columbus stands in midtown Manhattan, adorned with bronze miniatures of the three ships of the Genoese navigator’s first voyage, the Nino Pinto and Santa Maria, planned in 1890 and unveiled in 1892. Unlike the image of the Genoese navigator holding nautical charts and pointing to the Atlantic in Barcelona, or the image of Columbus with a compass or globe, in period costume, this Columbus stares over the land, saluting imagined inhabitants akin to a Caesar. More than encountering natives, as the bas-relief in Manhattan or Barcelona, Columbus in “Birth of the New World” evokes a figure with aspirations to global dominance, removed from time or space, a thoroughly post-modern figure of the discoverer who lacks maps, as if he followed inborn GPS.

His gaze is imperious, but does not scan the seas, or shore, but seems to ahve arrived with a new sense of entitlement, inflected by three royal crosses behind him, and in the relative immobility of his posture and weight, facts that Trump must have noticed or seen in a mock-up when it was suggested as a gift to the realtor who was negotiating the placement of Trump Tower in Moscow, and saw fit to place on the lot of the planned luxury apartments he had been promoting in Manhattan, as another second act to Trump Tower, when his fortunes and global capital were in decline, having just declared a loss in 1995 of $916 billion desperate to relieve some of his debt devised a deal forgiving half of the $110 million he owed, per Wall Street Journal, escaping his creditors in ways Fortune called truly “Houdini-like” and was eager to create a needed simulacrum of monumentality for the Trump brand that would magnify his own personal wealth in Manhattan and on the global playing field, as he aimed to $916 million loss he posted for 1995, or the millions he had been hemorrhaging of the value of Trump International that was rolled out in 1997, in an attempt to eclipse the filing for bankruptcy of Trump Taj Mahal in 1991, by securing a new monument of global conquest.

This giant statue was the first time in the final months of his Presidency, Donald Trump seemed to bond again with the symbolic status of statues as patriotic memorial, so that by May, 2020, during the social justice riots after George Floyd’s killing, he felt oddly impelled to affirm, almost repeatedly, the litany of statues, memorials, commemorations, or neoclassical monuments. From May of that year, he linked the eulogizing of statuary was paired with the end of the “downsizing of America’s identity” to the national wealth “soaring” an additional twelve trillion, concealed in increasing wealth inequality, describing funds “pouring into neglected neighborhoods,” presenting the Medal of Freedom to Rush Limbaugh, and “reaffirming our heritage” by in the State of the Union, lionizing the heroism of Americans as if a casting call for the Garden of National Heroes he suggested on July 4, 2020: Generals–Pershing, Patton, and MacArthur–and noble frontier figures like Wyatt Earp, Davy Crockett, and other heroes of the Alamo, or the Pilgrims from Plymouth Rock, largely white men, lamenting the lack of heroic statues, rather than affirming a commitment to living humans, and expressing shock and dismay at the attacks on neoclassical statues. Trump had returned as soon as he was elected President to reassert the place the Genoese navigator occupied in a proclamation celebrating Columbus Day the second Monday of October, praising his “commitment to continuing . . . quest to discover . . . the wonders of our Nation,” and, in fact, the “wonders of our nation, world, and beyond,” as if the navigator was indeed a basis for the proclamation of the future vision of the nation, as if replacing the vision of the nation in that other Modern Colossus of the Statue of Liberty, modernizing Manifest Destiny by praising the navigator for having “tamed a continent,” if he had barely arrived at one.

3. The planned monument was never built. But it evoked a mythos of manifest destiny many found a surprising embrace as a way to “reaffirm our values and affirm our manifest destiny” in the early days of the Trump Presidency. But Trump seemed to affirm his mysterious attachment to global transit of profits in the allegedly cost-free transport of a massive piece of statuary to be built on the Hudson River’s shores as a new way to claim public prominence for his lagging fortunes, jsut years before he first put his hat into a Presidential primary and declared his interest and possible intention to be United States President, as if to familiarize the nation with an idea that was striking by its improbability. The Hudson River, Donald Trump announced to the American press, was in fact the very site where “The mayor of Moscow . . . would like to make a gift to the American people,” a site to erect the massive statuary entitled “Birth of the New World.” He eagerly let it leak to the press after his return from Russia in 1997 that he would be instrumental in the arrival of a new monument for the city’s skyline, based on his negotiations with Russian oligarchs, and that the project hard to imagine as an extension of his own interests to immediately raise eyebrows of a tie: “It would be my honor if we could work it out with the City of New York!” While Trump International was a chain of luxury residences, the elevation of the statue as an image that confirmed his luxury residences as a global attraction were no doubt far closer in his mind than the consensus the new public statuary would imply. Did he realize that the gift was already rejected by two sitting presidents, Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush, who were approached by what was an ostensible gift of friendship for the quincentenary of Columbus? His image of a new logo for Trump International to show its global ambitions, unveiled in 1997, at Columbus Circle, has an eery parallel to the interest in adopting Columbus as a mascot for his new luxury housing chain, oblivious to the impropriety of placing a triumphant statuary of Christopher Columbus at his own other midtown properties, as if to personalize the contested icon of what had become a disputed and quite loaded figure of global triumphalism–a figure that was almost literally from another time.

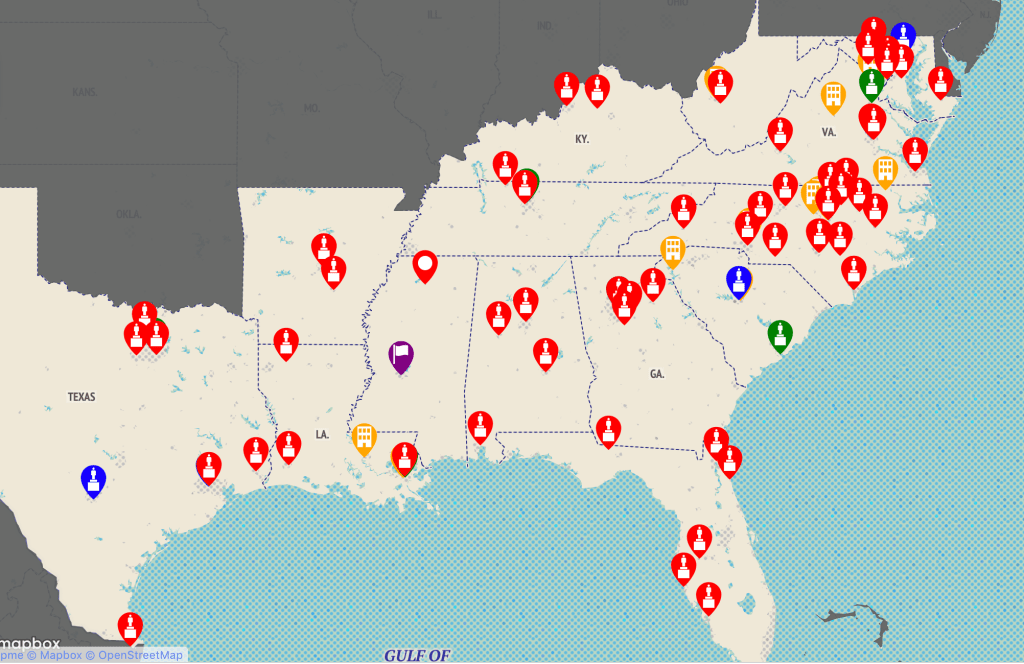

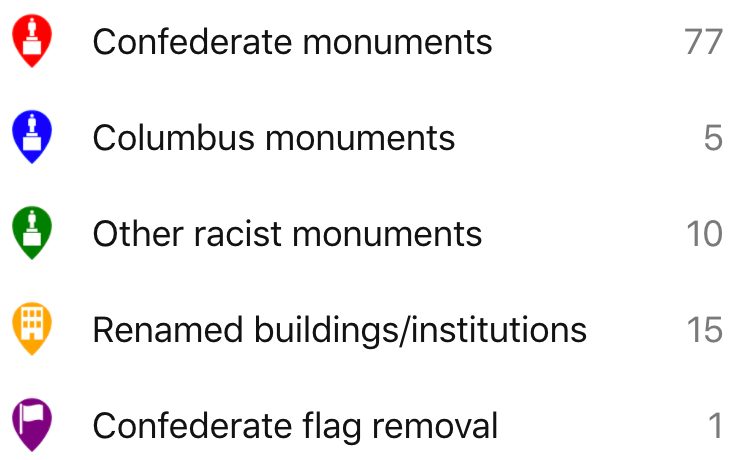

Trump bemoaned desecration of the monumental on the eve of leaving office addressing in his final rally, on January 6, 2021, bemoaning what he saw as rage against monuments, not a re-questioning of their significance, and cultivating an eery silence on escalating police violence. The danger of disturbance of monuments was only stopped by a law and order affirmation, lest, he taunted, “they’ll knock out Lincoln too,” necessitating the sentences for desecrating statues–“You hurt our monuments, you hurt our heroes, you go to jail“–to restrain the beheading, toppling, or besmirching with red paint of public monuments of confederates, slave holders, and colonizers in all fifty states, including the 1,749 statues of confederates that the Southern Poverty Law Center estimate were standing in the United States in 2019, 1,500 supported by the US government grounds; a sixth of monuments to confederates erected mostly in the Jim Crow era lie in black-majority counties, totems of a past white supremacist culture President Trump had found much support. As the call for the removal of statues that natauralize if not celebrate racism as part of the American social fabric, the reconsideration of confederate statues long prominent in many cities seems to have provoked Trump’s outspoken support for the very same statues as a sign of patriotism.

The statue of the instigator of the slave trade, Christopher Columbus, had claimed a special place in the political emergence of Donald Trump, and in the revaluation of public monuments, form the the civic fraying of debate about the status of Columbus that dates from the early 1991, when indigenous protests against the commemoration of Columbus began, and the proclamation in some cities by 1992 of Indigenous People’s Day. Trump’s attachment to the monumental an an emergence that seemed deeply tied to his desire for the monumental placement of an icon that might command statement was long tied to an aspiration for recognition: Trump claims to have long dreamed he might appear on Mt. Rushmore, perhaps explaining the ubiquity of his name on his buildings, and the satisfaction he drew from that. But the escalation of his drive for the monumental–and, indeed, his hopes for a border wall that might bear his name– may have began, not with his inauguration, but just after Trump Tower, in 1990, when Trump was flailing around for attention and for ways to escape his debtors, and negotiated the arrival from Russia of a monumental statue he imagined would stand in New York harbor–which Trump probably argued was the apt location for “Birth of the New World,” a monument two past Presidents of the United States had turned down, but Donald Trump, eager to please Russians, promised he would erect.

While Columbus was Genoese, and long a confirmation of Italian American pride, the image of a monumental figure of male Christian government that the Tsereteli statue, removed from time and space, staked an over the top monument of an image of the white, male figure of state we might long associate with Trump, a figure numerous American cities would rebuff in the 1990s, before it was relocated to Puerto Rico. The proposed statue marked Trump’s first flirtation with a statement of political monumentalism, inspired by ties to Russian oligarchs who patronized the deeply orthodox Georgian sculptor who had designed the towering neoclassical figure of a heroic navigator for “Birth of the New World.”

The monumental size of the statue of the navigator long deemed an icon of national genius was to upstage the monumental Statue of Liberty in New York harbor, at the end of the estuary, celebrating in monumental form the heroism of the navigator, more a symbol of rapaciousness and plunder but recast in bronze in monumental size as a liberator and conquistador of new lands that, before Trump appeared on Reality TV, would broadcast his achievement and Trump’s munificence on the skyline of New York to all its residents. Columbus would be cast in a new level of monumentality, and even aspire to the new language and logic of monumentality to which Donald Trump had aspired. While it is not clear why the monument did not advance, one suspects that Trump’s eagerness to accept the monumental statue of the Genoese navigator forged in Moscow’s oldest smelting furnaces, founded by Catherine the Great, and designed by the Georgian Zurab Tsereteli, would have been placed on landfill in a Trump project in the landfill of the trainyards in the Hudson estuary, unable to support the ponderous bronze assemblage weighing 660 tons–the ballpark figure Trump cited that oddly hovered near the number of the beast.

Did the negotiation of a figure of rapaciousness as a symbol of the nation find its way to the sponsorship of Donald Trump only by chance? The image of a white conqueror that Russian elites offered to Donald Trump at the same time as he pursued ways to export his brand to the post-Soviet oligarchs in a gambit for greater monumentality was a moment when Trump’s language of monumentality–the expansion of Trump Properties to Trump International and the expansion of Trump Tower in Manhattan to a possible chain of Trump Towers in global capitals–suggested a stagecraft of hotel promoting that was met by a triumphalism of staking his foray into national politics by rehabilitating the figure of Columbus as a hero of globalism and economic conquest that would dwarf the figure of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor, as if to cement the gift of Russian oligarchs beyond the French Republicans.

The timing of such an encomia to the rapaciousness of the Genoese navigator as an emblem of global economic ties was perfect. At the very time that Columbus’ celebration as a national hero was being questioned, that the post-Soviet government of former Russian President Boris Yeltsin had once offered a sitting American president–and attempted to offer to a second–that Trump, during a visit to Moscow ostensibly to plan a new residential tower on Red Square, acceded to being amenable to erect on shorefront properties he was developing. But perhaps the biggest irony of Donald Trump’s attempt to promote this monumental statue was that it was a way of selling his own success to an American public, at a time when he was in fact surrounded by mounting debt, having trafficked in debts for most of the 1980s, and in need of an illustration of triumphalism to promote his own pet project of a new West Side development, that would be the site where he proposed the statue of the navigator who had claimed to “discover the New World” was planned to be erected.

If Trump had argued that Trump Tower demanded recognition as “the eight wonder of the world,” the statue of Columbus that he sought to importing to the banks of the Hudson River, or the landfill of the former railway yards where he projected an exclusive new luxury complex, provided a possible basis to erect the monumental bronze statue of Christopher Columbus, designed by Soviet sculptor Zurab Tsereteli, a Georgian member of the Orthodox church, far larger than the statue of Columbus in the act of sighting land from atop a column in Barcelona, in 1997, before two sails billowing with wind, each decorated with a cross, in the act of bearing Christianity to the New Wold as an agent of the Royal Majesties, Ferdinand and Isabella. This invocation of the myth of transatlantic travel–Columbus had never visited New York, sailed in the Hudson, or on North America, save Caribbean islands, had grown in 1892 as part of an American decision to stake claim to the theater of Central American islands as a province of hegemony. As the monarchs were storing all maps of routes to the New World as tools of global power, the throwback image of a Columbus offered a basis for Trump to set his sites on global markets, by 1997, far outside New York, and provided one of the strongest ties between Trump and Russia, as Donald was hoping to build an outpost for a newly branded Trump International, by an actual monument that would have been the tallest statue in the western hemisphere to affirm the global scale of his enterprise.

But the image of this immense statue of a robed Columbus who would be saluting Mnhatttan Island, would be a theatrical addition to the six luxury towers he was planning on the West Side, at a time when Trump was all but crumbling under debt. Would the image of Columbus, shown saluting Manhattan Island and perhaps hailing the towers of Trump and the foreign capital that had funded their construction, as the Russian-made statue that Trump brokered was billed as arriving in New York fully paid for, with oligarchs covering the cost of its transport and construction, aside from the installation of the behemoth on the landfill where Trump planned to build. How the monumental statue would appear on the New York skyline, or be integrated with Trump residences, was never apparently discussed let alone described, so much did Trump trust the sense of theatricality that the erection of the statue would immediately add to his image in the city, which was in need of considerable rehabilitation.

The statue met Trump’s insatiable taste for monumentality, even if the image of Columbus as an elitist mariner and royal emissary was about as out o step with the histroical image of Columbus or his place in a democratic tradition. Columbus stood as if arriving and claiming possession over a nation, echoed a belief in manifest destiny that was more than out of step with the times. It idealized a sense of conquest and of rapaciousness as American, if the recalibration of the legacy of Columbus as a national hero had been percolating across the nation for some years, as many questioned whether the navigator who had been heroized by Italian immigrants as an icon of their ties to the nation of America and an image of their own whiteness, was now reclaimed as a logic of the capitalism of plunder, materialism, and enrichment, rather than the social and civic order that the image of Lady Liberty, standing atop the chains of enslavement, was intended to communicate.

Unlike the stoic monuments of Columbus as a world traveller, the statue of the emissary who arrived in classical robes was an odd appeal to a type of classical statuary, togaed and raising his right hand in a gesture of imperial salute, to exchange for the entry of Trump Properties to Moscow, Is this triumphal image of Columbus not an image of enrichment, as much as Christianization, and image of neoclassical monumentality who masks the violence of disenfranchisement and conquest! In raising one hand worthy of Mussolini more than Augustus, the sttue all but invoked a “Doctrine of Discovery” to lay claims to the New World, unlike Liberty,. For the figure of Columbus lays claim to the ownership of the land and its rulership by a sort of Christian militarism, without a book of laws or declaration, or respect for laws, viewing the nation from atop a small symbolic caravel. It did not make a difference that this figure was so dramatically ahistorical, with his hand on an anachronistic rotary wheel, without a compass, sighting device, or indeed a map.to navigate or to conquer and stake his claim.

The monument did not have need of either–if all are the tools included in Columbus statuary, for it was actively rewriting history and memory alike. In the service of a banal monumentality, closely recalling the cartoonish monuments Tsereteli erected across Moscow, and send to different posts in the world including Paris and New York, the oddly cartoonish navigator is ostensibly a new map of the nation, as well as a new image of global power that had been offered to American Presidents as a gift of the post-Soviet, but that Presidents Bush and Clinton had alike demurred, perhaps seeing something unsavory in selecting a gift form a Russian President as an image of the American nation. This image famously appealed to Donald Trump, who savored its monumentality, the reputation of the lauded Russian Georgian sculptor Zurab Konstantinovitch Tsereteli, and his reputation for controversial monumental art. Trump had a high tolerance for what might be called kitsch of opaque monumentalism. The frozen figure of Columbus removed from time and place is an assertion in empty air, a floating signifier that only seemed to float, standing on a ship in triumph, a made-in-Moscow massive icon of unheard of magnitude, that would be destined to the largest in the western hemisphere. This project to re-monumentalize the image of Columbus in the act of magisterially surveying a continent on which he had barely set foot, as if to justify claiming the conversion of the New World’s inhabitants, offered a claim for Trump’s own arrival on a global stage, funded by underwater financial currents, laundered funds, and foreign backers–many of whom seem to have continued to support his candidacy in a bid to be US President in 2016 and 2020, often through the same contact that Trump wanted Russian oligarchs to talk about the statue’s arrival, then-Mayor Rudolph Giuliani.

Donald Trump was more familiar with identifying himself with a monument–witness how he became identified with the “prop” of Trump Tower that maps that became a primary residence, a site of his corporation, and a studio set for his Reality TV shows, Trump wanted a monument that would announce his status on a global stage, allowed him to rehabilitate him as he emerged from a mountain of debt, and solidify the claims for a new monument in Moscow, a new Trump Tower a decade later, for which the agreement was to be greased in transactional fashion by the acceptance of an odd statue of Columbus that would effectively remap the nation for Trump’s personal gain. The first second act after Trump Tower, first announced in 1980 as a triumph of the urban skyline, would be erection of an image of Columbus that would similarly dominate the urban skyline, sacrificing debate about an icon of the nation and indeed national identity to meet an undying thirst for monumentalism.

And if Trump repeatedly staked his later Presidential candidacy on his ability to provide the nation with a new monument, a monument to inspire renewed faith in the “sacred bonds of state and its citizens,” as he promised when he unveiled a plan to cut e legal immigration by half soon after his election in 2017, he announced he would run for U.S. President from the atrium of Trump Tower, the nerve center of Trump International, by staking his bonds to television viewers across. the nation by the promise “I would build a great wall,” as a concrete barrier along the United States’ southern border, winking acknowledging “nobody builds walls better than me, believe me” as if referring to the monumental atrium where he spoke. If Trump repeated the claim “I know how to build” and “I am a builder” in an upbeat optimism of the nation, as if the talismanic power of Trump Tower established the legitimacy of his ability to deliver on global wealth to deliver fantastic power, if not a personal fantasy, as he consciously deployed the Tower as an image of power, making good on the promise to deliver a building of unprecedented desirability to Americans and height to the New York skyline as he navigated its construction from 1979 to 1983, the potential addition of a statue of Columbus, the colonizer converted to a heroic figure and White Christian Man, int he 1990s provided perhaps more than a road not taken.

The entrance of this monumental Columbus, proposed for the estuary of the Hudson River, where Henry Hudson, himself in fact once an agent, as it happened, for the Muscovy Company, arrived in New York Harbor in 1609, but Columbus never approached or sailed, would be the first great international showpiece Trump would have promoted as his realty company was pivoting global, by rebranding and expanding as Trump International, on a global stage, as a showman seeking the least modest image of grandiosity able to be imagined. If Robert Musil, the Austrian novelist and critic, had in 1925 imagined that one often passes urban monuments “without [having] the slightest notion of whom they are supposed to represent, except maybe knowing they are men or women,” as you walk around the pedestals of statues that in their remove from the urban environment almost repel attention, leading our glance to roll off, and repelling the very thing they are meant to attract as water drops off an oilcloth, the showpiece that Trump was aspiring to bring to his Hudson River properties would cast Donald Trump as presenting a new image of the nation. The fantasy that Moscow fed Donald Trump to Americans was modeled, like the Statue of Liberty, after the Wonder of the World of the Colossus of Rhodes, was difficult to deny for a man who had declared Trump Tower a Wonder of the World, and attempted to replicate a second global wonder in Atlantic City in Trump Taj Mahal, recently built for $1.2 billion as “the eighth wonder of the world,” but the 360-foot bronze statue of Columbus Russian oligarchs had promised to deliver was. a monument he seems to have siezed on to promote his own public prominence in Manhattan.

Trump’s promise of the size of the statue and its ostensible value–$40 million!–would be a sort of windfall that would serve as a small downpayment on the $916 million loss he posted for 1995, or the millions he had been hemorrhaging of the value of Trump International as Trump Taj Mahal filed for bankruptcy in 1991, or the deals he had cut with banks that unloaded his personal debt for about $55 million–half of what he owed, in what Fortune had marveled was a “Houdini-like escape” from his creditors, having walked away from personal debts to relaunch his hopes for a real estate empire without the encumbrance of any federal tax claims at all. The monument to Columbus would relaunch his brand, Its size concealing that Trump’s increased search attracted illicit flows of Russian money in hard times to puff up his grandeur and indulge his vanity, in the guise of promoting patriotism, even if the image of Columbus it would advance. At the same time as Giuliani proclaimed Trump’s “genius” during his later Presidential run was revealed in his ability to financially rebound from the devastating indebtedness of 1995, the statue of Columbus would be a similar dissimulation. The massive statue–taller than the Statue of Liberty!–would be an illustration of his ability to create a “comeback,” and to reburnish his public citizenship. The statue transposed from a register of patriotism to promoting a residence would have been the fulfillment of Trump’s past plans to create on the same site the very tallest building in the world of seventy-six stories– complimented by a statue the tallest in the western hemisphere, whose maquette Trump had already presented publicly with paternal pride. The spire of the newly planned central tower would dance in dialogue with a statue of the discoverer, a sort of grotesque dialogue of monumentality commanding global attention, demanding that the world recognize Trump’s return to the top of his game and reclaiming his status as a global real estate developer.

Hopes for marking the complex to be named Riverside South on the banks of the Hudson River in New York City of a monumental bronze statue of the fifteenth-century navigator Christopher Columbus cast in Russia–“Look on my works, ye might, and despair!“–adopted colossal statuary of a figure Trump has affirmed as central to the nation–and preparing for its settlement by Europeans as President as a promotional illustration of his latest property’s value and its status as a global destination. in a new language of architectural monumentality, unsurpassed world wide, a showpiece that would be a credible second act for Trump Tower that would supersede the tower Trump had planted in the New York skyline with an even more monumental eyesore that no one in Manhattan could ignore.

Trump declared himself considering a Presidential run in 1988 to Oprah, offhand, and was perhaps destined to intersect with the boondoggle of a statue offered to President Clinton and President Bush in 1990 and 1994, respectively, who seem to have demurred or declined the grotesque statue that they saw mostly in models, one of which was brought to the White House by Boris Yeltsin in 1990. If the prototype was sent to the Knights of Columbus in Maryland, destined for the harbor, the small model that was on offer at an auction house in Florida suggests the circulation that the proposal for this statue of a man on a boat, the very incarnation of individual agency in relation to the New World, removed from any networks of power or of funding, was intended to make: the odd figurine foregrounding the navigator’s agency unsurprisingly fell on deaf ears, but the token of globalism appealed to Trump, so delusionally sure of his own genius as a realtor to win a statue to take home to New York.

The megalomaniac sculptor Tsereteli fashions himself as a builder for new global emperors, and invested Columbus in a roman toga, as he would Peter the Great, in the colossal monument that finally appeared in Puerto Rico near San Juan off the shore in Arecibo, far closer to the Genoese navigator’s actual itinerary, after the megalomaniac sculptor had shopped it around the globe, hoping the ridiculous sculpture would be realized.

Trump, laden with debt at this point in his life, would have seen in the statue the opportunity for global symbolism, able to restore his public reputation and image of public citizenship in New York, and balance the exclusivity of dwellings destined to be removed from the city and for the superrich with a front of civic generosity and showmanship. While the maquette of Tsereteli’s statue was probably glimpsed while he was in Moscow, Trump was quick to adopt the monument of Columbus as something of a pet project that he might advance his hopes for a Moscow hotel and tower to Moscow’s corrupt mayor and other post-Soviet oligarchs, promoting a gigantic statue of the Genoese navigator in 1997 he imagined might benefit from an assist from then newly-elected mayor Rudy Giuliani, who Trump must have imagined would comply with the role of past mayors in acceding to the bending of local regulations and zoning requirements to arrange sites for his Manhattan buildings. Trump was for his part happy to promote the arrival of the monumental statue as if it was imminently impending, as a true showman, telling Michael Gordon of the New York Times with satisfaction that “[the deal]’s already been made,” while not mentioning the Russian offer had been rejected by two American presidents, allowing “it would be my honor if we could work it out [that the statue be erected] with the City of New York,” on a stretch of landfill he promoted for his properties, as if he had brokered a deal on behalf of the city, only requiring the Mayor to sign off. The Master of the Art of the Deal boasted a done deal, anticipating approval of Giuliani to erect the 660 tons of bronze that he claimed valued at $40 million, on the development site where Tsereteli ostensibly desired it be located, in anticipation of the completion of the stalled construction project that he hoped would be a display of super-wealth for residential towers to be built, in hopes that they would find their counterpart in a monumental prop of global kitsch.

It is apt the monument was relocated to Puerto Rico, on whose shores the historical Columbus actually set foot, and renamed from anisland known by Taíno inhabitants as Borikén (Spanish Boriquen), “land of the brave lord,” to a city named after Saint John the Baptist. The commemoration of Columbus in San Juan occurred only in 1893, to be mirrored in the new centennial by the 2016 outsized statue largely visible to luxury liners arriving at or departing San Juan.

Although the “Birth of the New World” was never built near New York, the promise of the arrival of the statue, first planned to coincide with the quincentenary of the Columbian voyage, but long languishing in storage lockers on both sides of the Atlantic, demands exploration as a moment to examine the trust Trump placed on a monument albeit a second-hand one forged in Moscow, for staging his own triumphant return to a global stage. No one had ever seen so large a statue of Columbus–the figurine that survives which the sculptor seems to have made to shop around the discarded project–but the idea of redeeming an image of pompous grandiosity from the dustbin of history on the properties he sought to developed on the West Side in the mid-1990s, when he was clawing himself back to a place on the global stage, was a new fantasy project that Trump had hoped to sell the the nation. The plans to erect the monumental statue, double the height of the statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio De Janeiro, preceded his project to run as a candidate for President with the Reform Party, a fledgling renegade party begun by former Television Star and World Wrestler Jesse Ventura, later placed in Puerto Rico in early seven hundred of bronze, on the port city of Arecibo, Puerto Rico, shortly before Trump was elected U.S. President, was a fantasy project that

2. The triumphalism of the statue of Columbus he boasted to bring to his properties on the Hudson had been proposed to three earlier U.S. Presidents as a gift for the Columban centenary that would cement the post-Soviet friendship between the United States and Russia, but the odd arrangement that emerged from protracted real estate negotiations in Moscow had Trump promising the deliverable of a site for the statue of Columbus on his Hudson river properties. Trump’s boasting of Trump Tower as a wonder recalls the huge attention he assigned recreating a modernized version of an actual global wonder–the ancient Colossus of Rhodes–in a bronze statue of Christopher Columbus, taller than the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor, gifted to the American government as a “Modern Colossus” that claimed to celebrate freedom of the same height as the ancient wonder of the world, all but intended to be situated on the Hudson to contrast with the slightly smaller Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. The “white monument”–proclaiming the truth of Dead White Man History–aligned Trump not with conservatism but a transactional story of glitz, grandiosity and power that provided both a telling warning, touchstone, a recapitulation for Trump’s entrance into a political career. If never built, the statue provided a deeply troubling image of Trump’s tie to the fetishized role of the navigator, “Behind [whom] the Gates of Hercules;/Before him not the ghost of shores,/Before him only shoreless seas,” and an obscene denial of historical actuality.

The monument would have been impossible to not entertain as a prop of global power, as much as of his own sense of import, and offers a model of the sort of monument he sought–and the deeply transactional nature of Trump’s notion of global power that is important to recall. As Donald Trump had ridden the monument of the border wall to the office of the Presidency in 2015, as a sign of his ability to contest the political status quo, he indulged himself in imagining the monument that symbolized the scale of efforts to curtail immigration Trump would pursue as President by Executive Orders and diktat, days after inauguration, the border wall perhaps demands to be seen as a “prop”–as Trump the realtor admitted he considered Trump Tower a prop for his promotion of real estate worldwide with Trump Properties during the 1990 interview, as if the hundred room triplex he kept for himself in the building were secondary to the public status the building afforded him. To be sure, the penthouse he shared with then-wife Ivana were sites of almost regal lifestyle, importing a version of Versailles to Fifth Avenue, but as “props” created a lifestyle and a global status–he confessed Playboy with some facetiousness, be as happy in a one bedroom apartment–but valued the “gaudy excess” of the building to “create an aura that seems to work.”