The “Central Park Effect” describes the interrupted avian migration that annually funnels a range of species of migrating birds into the trees of Manhattan’s Central Park. As they move along the great flyways of the eastern seaboard in search of a roost, the patch of trees amidst urban canyons of inhospitable anthropogenic landscape seems an area with something like habitat, whose edges offer a target to rest on a flyway that, by the time it passes the northeast Atlantic, is nothing if not overbuilt. If the park long held the space for repose on promenades and staged wilderness, birds have made it a home, amidst the anthropogenic landscape of the eastern seaboard offering far fewer and fewer roosting places during migration, recognize the park’s arboreal density as the last place to stop on a long trip north.

For the urban resident, the interruption is idyllic: the refugee from rural New England, Frank O’Hara, drank up the urban landscape he arrived in 1951, through his death, in ways that didn’t need more greenery than the Park offered him on lunch breaks. “One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes,” he wrote, in dialogue with Walt Whitman’s poem that takes its spin from Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery, while allowing that the city had made him so urban “I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy.” As O’Hara exultantly catalogued the hidden space of New York’s landscape, inspired by the movie houses, Manhattan Storage & Warehouse Co., and cavernous subway, the Park’s trees were enough, but also suggested about as much of the rural that he could stomach in his urban aphrodisiac that was the city that was the “center of all beauty.”

If the early trees planted tin the carefully landscaped arboreal island was hardly bound by built space, and wasn’t really an island, but modeled after European beaux-arts parks, filled the settlements of squatters in upper Manhattan–Irish pig farmers; the African American Seneca Village; gardens German immigrants presided over–with a monumental space of curated trees, whcih a hundred years after its founding had fallen into some state of delapidation, as huge towers surrounded its walled perimeter.

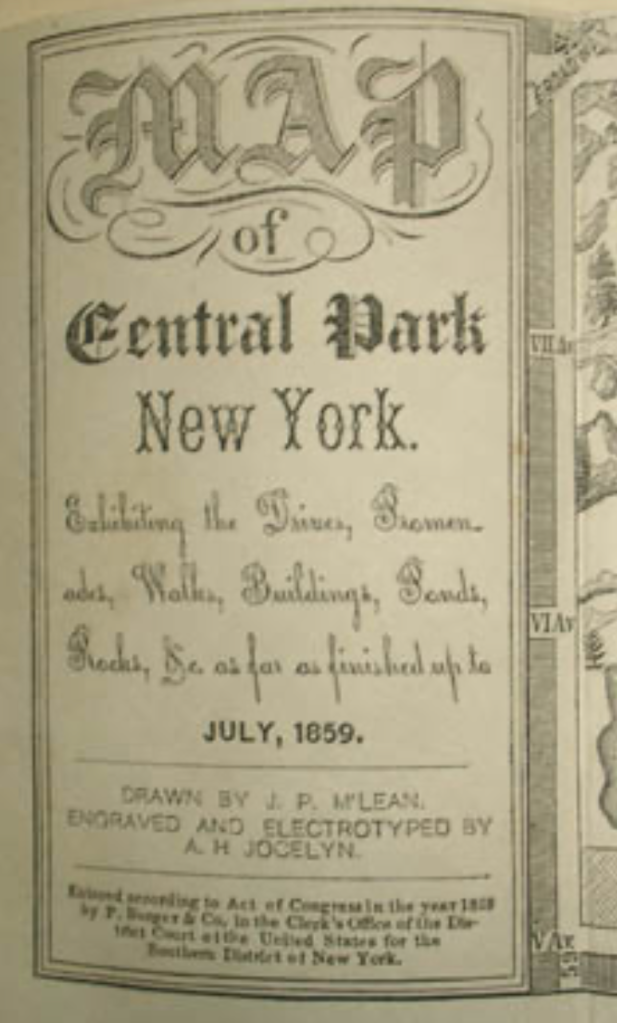

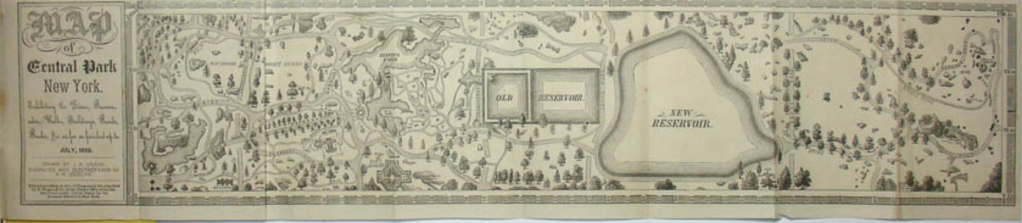

Few thought to catalogue the trees that now populate New York’s Central Park, the tide has turned. Back in the mid-nineteenth century, the expansive 1859 fold-out Visitor’s Pocket Guide to the park’s principle ponds, opened a prospective on the newly wooded regions of the park, taking time to caution visitors from disturbing the picking of any berries or flowers, as if it were a site of nature, lest they disturb any “construction, tree, bush, rock or stone.” Its trees appear carefully situated in rows, and planted beside promenades, in stark contrast to the arboreal density today. The expansive seven-sheet fold-out map was probably based on the original pen and ink design drafted by Olmsted and Vaux as a proposal for an open, recreational space in the city, the Greensward Plan, with many paths not yet constructed and others eliminated by the time it opened in 1857, as a truly bucolic space for strolling, rather than the wooded enclave that the park has since become. The product of human work of construction of some 5,000 laborers–a miniature army responsible for paving, bench-making, constructing tunnels and bridges, lighted electric lampposts, and wiring, as much as planting trees, the luxury of the park displaced the squatters’ shacks that filled the region between Fifth and Eight Avenues, bound by 59th and 106th Street per the City Council’s mandate. But trees were hardly the planners’ main intent in imagining what they called a democratic greenspace, a curated wilderness that might substitute for the dilapidated sites for squatting of the unhoused on the then-margins of urban life: the promise of a “life in the woods” was built just three years after Henry David Thoreau had waxed as a tranquil remove from urban life in Walden (1854) would have been realized in curated fashion as a sense of “wildness,” if not of lake-like reservoirs, that urban residents fortunate enough to live near to could retreat.

Map of Central Park New York. Exhibiting the Drives, Promenades, Walks, Buildings, Ponds, Rocks &c. as far as finished up to July, 1859 Courtesy George Glazer Gallery

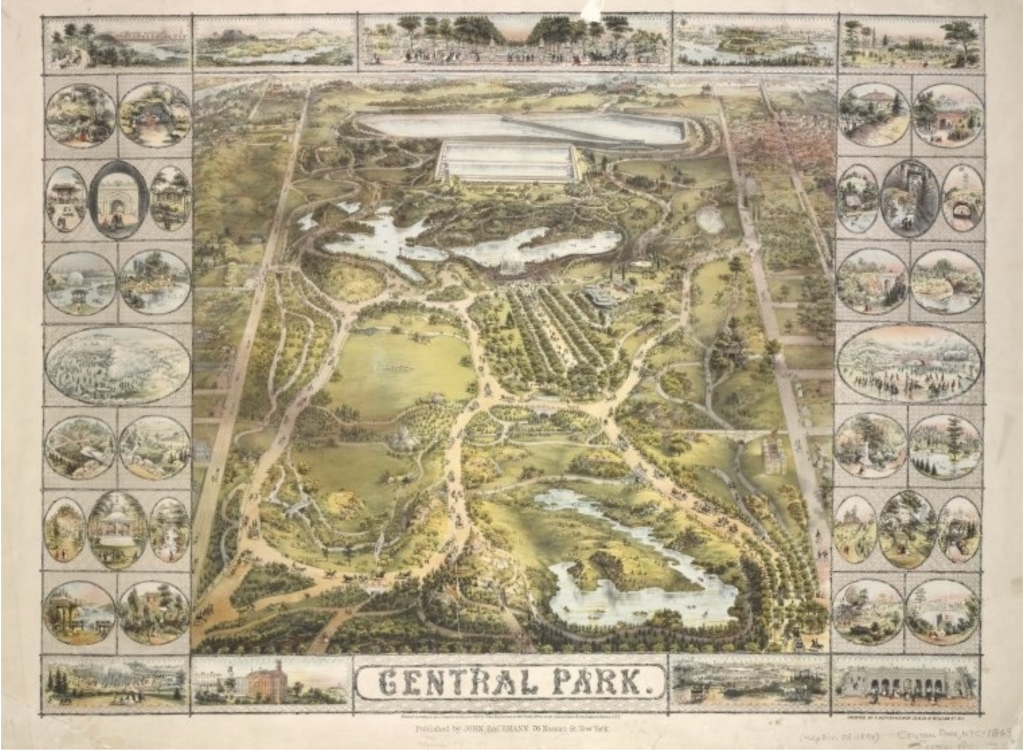

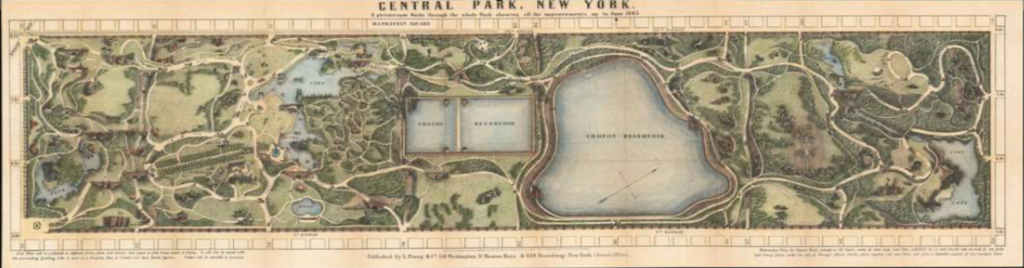

The process of the planning and planting of trees proceeded by the time of the detailed lithography that Lewis Prang seems to have copied it in a form–“thin paper to fold, heavy paper to frame”–he hoped to distribute among realtors of surrounding lots, revealing a park whose “every tree and bush, as well as every arch, roadway, and walk has been placed where it is for a purpose,” as Olmstead boasted, a space urban residents might wander removed from its grid, as if to find pastoral respite from the density of urban lives. The German-American engraver Lewis Prang who desired the work, who began a chromolithography practice after emigrating, later finding notable success in chromolithographs of maps of Civil War battlegrounds, including maps able to be interactively annotated by blue and red pencil to trace the progress of armies, completed this “picturesque guide through the whole Park” in June, 1865, as what must have been a celebration of peace-time, printing it in full color only some weeks after Civil War hostilities had ceased.

Central Park, New York. A Picturesque Guide through the Whole Park, showing all the improvements up to June, 1865

How to call attention to the variety of trees that have come to populate that unpredictable planned green space of Central Park, to catalogue its rebuilt pastoral? If the park was long seen as a site of danger in my youth, long a nocturnal site of cruising and unplanned encounters, the park planned around the Central Park is lauded for modeling the abundance of urban nature as if in negative to the built space of surrounding skyscrapers that roost around its edges.

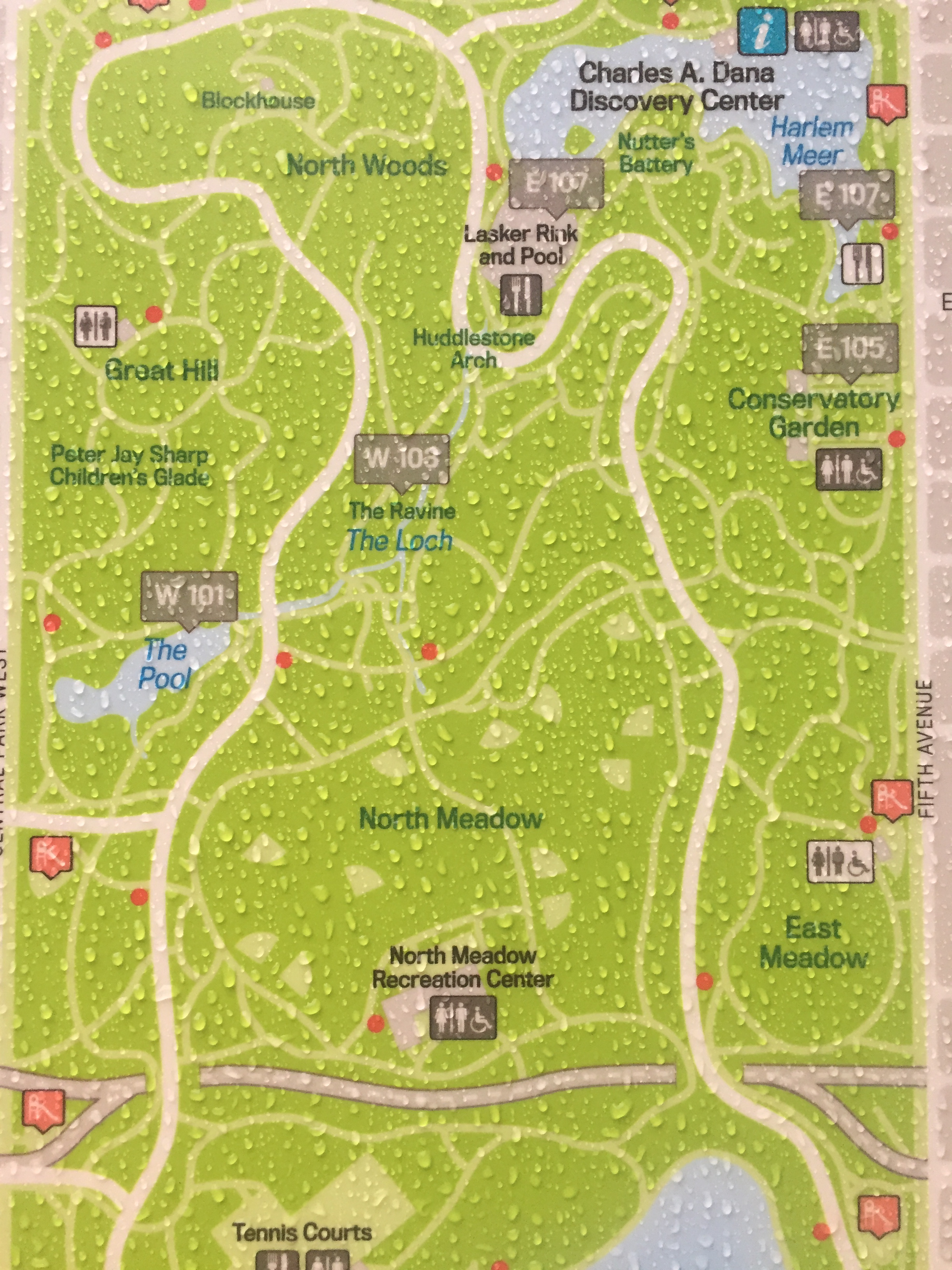

The way we map the park on the subway, indeed, suggests it is somehow magnified as a needed refuge for those to remember as they are coursing in cars that rumble on tunnels underground, far from any sense of open green: if the park is magnified in the famous transit map to afford a greater legibility of the tangled web of midtown lines that twist like branches or snake like roots of the circulating urban collective, it is important to remember that its lakes exist, even if its trails need hardly be mapped for audiences orienting themselves to public transit routes. We map the park, whose green provides a pause and respite from the grey concrete facades of buildings, as well as a site for strolling, by a flat lime-green interruption of the urban grid in our public maps, as if the park was an abrupt interruption of the tan city blocks, cool blue ponds creating a shared space of reflection in a landscape dominated by private property and expensive residences. And there is a sense of lack, perhaps, or wanting, that the cartographic silences of that pea-green space open, like a yawning opening traversed by busses along curved horizontal line, set apart from the urban grid.

The subway map affirms, in a weird remove from the rider who is traveling underground, a removed oasis of sorts, ringed by a tan frame of muted buildings–as if a place to experience wilderness, or a curated sort of wildness.

Created in the parks movement that redesigned urban space removed from unsavory elements and moral lassitude, and restored as a reprieve from the pace of urban life, the rebirth of the parks as open green-space has recently occasioned the first complete census of individual trees, those often uncounted inhabitants of Manhattan island. And each tree has been mapped, in recent years, to allow one to voyage through the space of planned trees, migrants, and recent arrivals of conifers and other volunteers, joining the staid oaks, elm, and London Plane tree.

The trees have been counted in Central Park, unpacking this light green space in an enumeration or ‘green census’ cartographers Ken Chaya and Edward Sibley Barnard created. The result is a deeply ethical way of directing our attention to urban space, in a comprehensive map of the tree space often rendered as a stretch of undifferentiated lime green. Indeed, the counting of large-trunked oaks, maples, individual pines, and sturdy sycamores in all their varieties offers a detailed abundance that is rarely evident in the parks maps that adopt a single cool shade of idyllic green, and offer a sort of palimpsest that will reward map-readers to pause over, examine, and explore–and indeed pore over, with the botanical level of detail and connoisseurship that the earliest planners of the park might well have appreciated and enjoyed–if not expected of city-dwellers.

Who wouldn’t have expected as much from urban sophisticates?

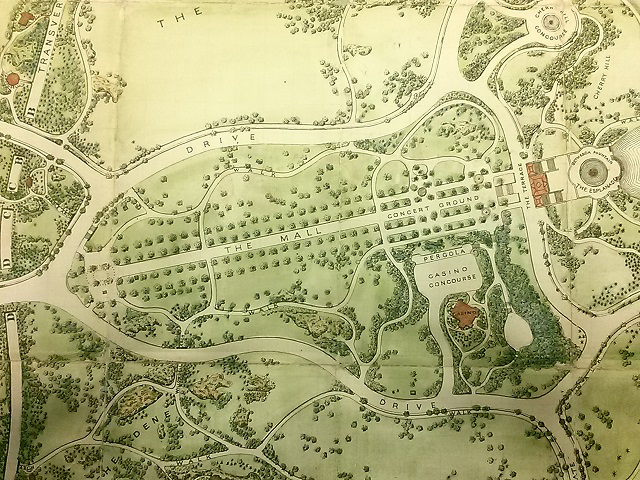

Map of Central Park: printed for the Department of Public Parks, 1873 (detail)

Yet today, the often-internalized map of the park of light green, far more familiar to all city-dwellers, may risk perpetuating an alienation from its dynamic urban forest, and obscuring the careful level of its botanical detail, or the accumulated palimpsest of urban habitats of its biodiversity. The vivid light green of most maps of Central Park may be muted, but seem rendered almost life-like in the rain–even if green is a generic “greenspace” it is one to be valued, and walked around on its circuitous paths, a space that is a distinct interruption of the equirectangular grid of the built city, and a respite from its straight lines and sheer heights. One can see not urban canyons, but the sky.

In part, the duality of Central Park as rural and urban captures the hybrid identity as an urban park. Even though the park seems to lie somewhat incongruously at the very center of Manhattan, as if the apparent preserve of trees and urban wildlife is defined by its porous relation to the urbanized setting of the park. If Central Park was designed in the movement of urban greening and public space, as a site of health and interruption of urban life, the park is increasingly more of a heterotypic combination of urban activity, designed built spaces, and manicured wooded areas, a refuge where Manhattan is in a sense perpetually present, not only bur urban sounds, traffic, and lifestyles, in a dyadic relationship that seems captured by the fact that it offers not only the sole open space to inscribe the toponym of the island in subway maps.

In such maps of urban transit, it may be that Central Park acts less as a park, than it serves as a totem of urban space; the park holds the bold-faced word “MANHATTAN” that identifies the city, its flat green spaces and clear light blue lakes crossed by ribbons of white roads, indicating its nicely settled position as secure in an urban grid, as if fastened by crosstown routes, yet readily available to urbanites at multiple entrances as a site of repose. The image of the interruption of urban space we encounter on subway cars with regularity reminds us of the existence of open green space which we can access, even while we ride in eardrum shattering rumbles of subway cars coursing on old tracks while winding one’s way downtown to one’s destination. Is it an important reassuring reminder of the existence of open spaces that are in fact accessible, even while we may not feel it, nearby?

The combination of nature and skyscrapers was a unitary construction, several ecopoets have observed, a conundrum or urban nature explored by ecopoets who take up the gauntlet that the urban spaces throw down. When the poet Gary Snyder described his arrival in New York City, he evoked an ecosystem blending nature and culture that began form its trees and moved settle throughout the island’s sidewalks, streets and skyscrapers, even as it clung to the edges of its shores.

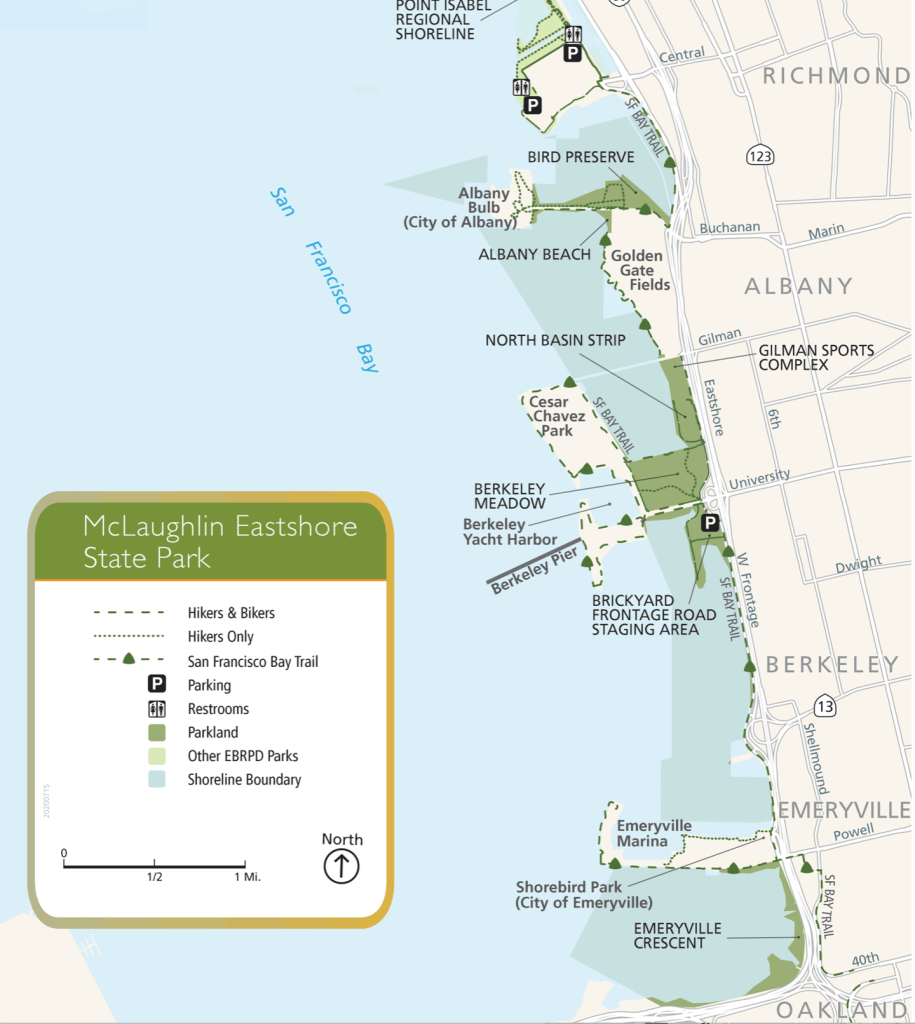

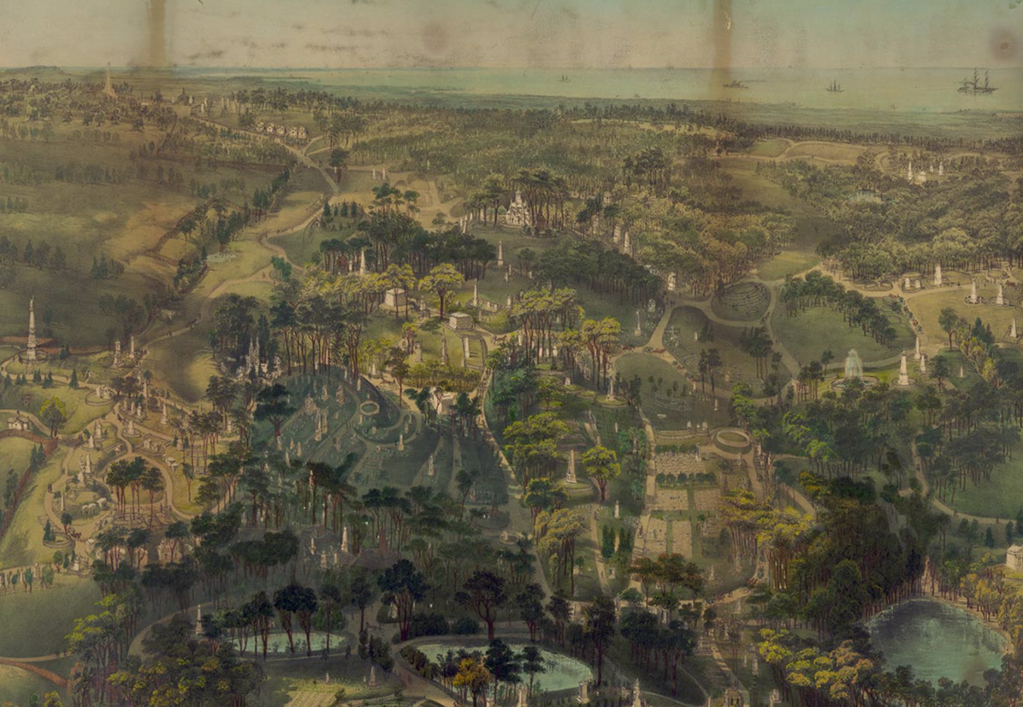

If the winding paths of the park were built as a space of democracy, modeled after the popular Garden Cemetery Movement of such exemplary success in the creation of Greenwood Cemetery as a preeminent public space of trees, winding roads, lakes, and monumental graves in Brooklyn–the trees and wooded regions central to its appeal.

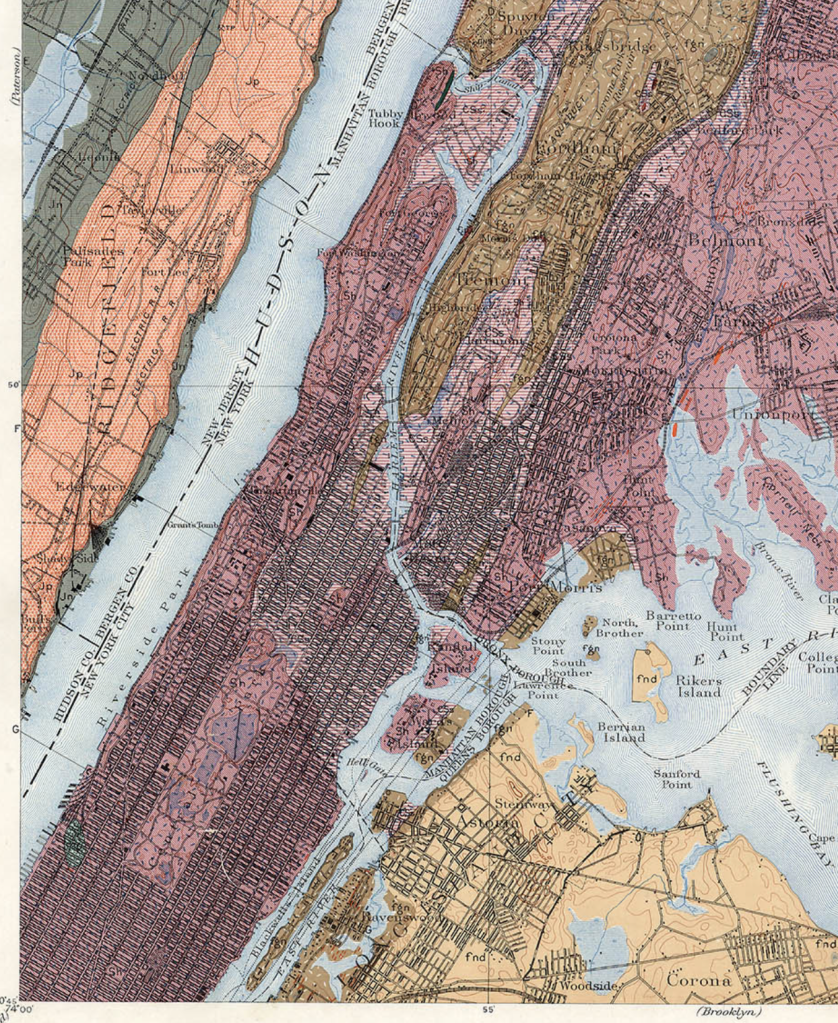

The sense of the showcasing the green space of the park had declined considerably, of course, by the 1980s, when Gary Snyder admired by the crowded built environment of New York as an ecosystem–or rather as a “deep ecology”–in “Walking the New York Bedrock,” careful attending to the juxtaposition of its trees in the steel skyscrapers of its overbuilt financial hub. The ecosystem was vibrant, but removed from wildness, if oddly emulating it in its crowded urban density upon its paved grid and steel and glass towers; helicopters like insects “trading pollen,” above skyscrapers competing for photosynthetic abilities, sirens coursing through its valleys and paths of subways like lichen rooted underfund. Snyder sung the collective recreation of a lived connection to living landscapes, the Central Park Conservancy was in its early years. The dolomite and schist that provide the basis for the actual “bedrock”–the basis for the rich growth of foliage across the island, and support offered its ecosystem–resting atop a thick bedrock of metamorphic Hudson Schist, marble, and dolomite.

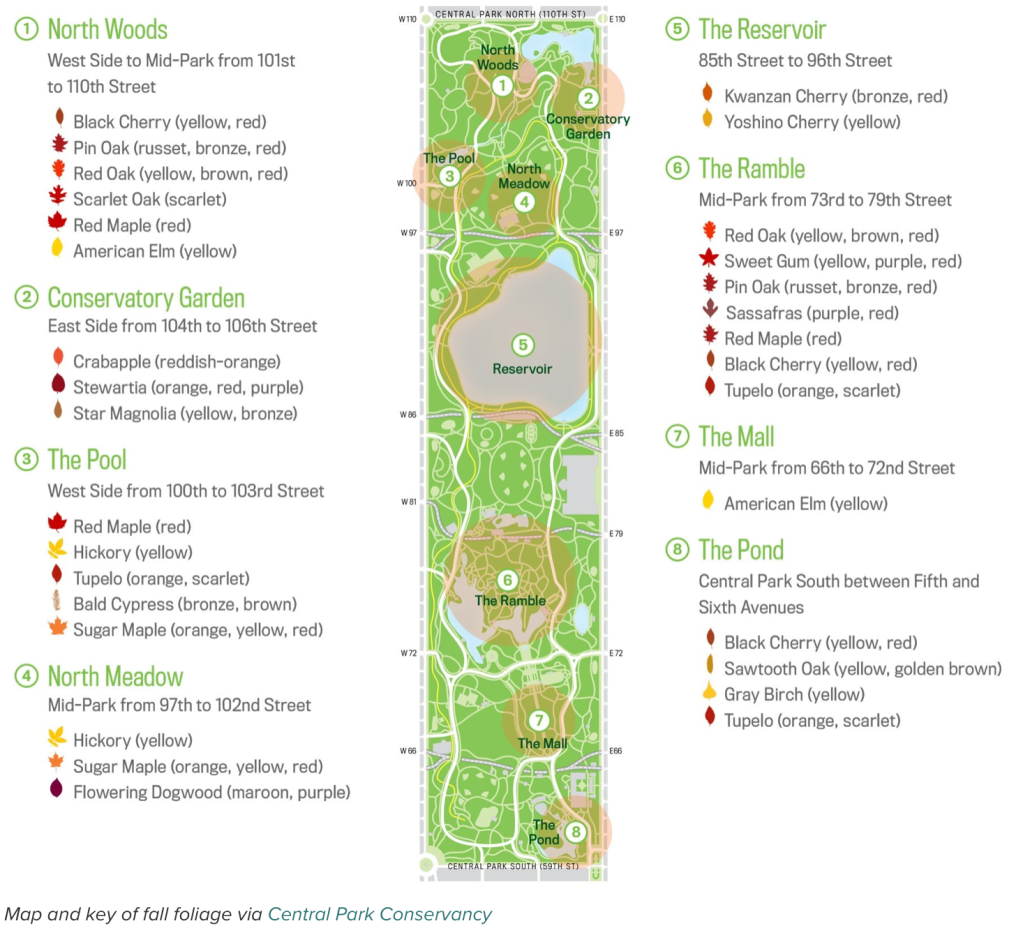

Snyder has meditated on the human relation to the built as a retraction from the wild in The Practice of the Wild (1990), which flippantly denies the vital sense of the wild in human life. Snyder wrote about the built the connection to the lived landscape that Snyder located in its wildness that remains in many natural environments was increasingly restored and retained in New York, where, as Snyder noted “there is nothing unnatural about New York City, or toxic wastes, or atomic energy…,” the trees which introduced and whose presence punctuate the poem were foregrounded in Central Park in the very years that Snyder wrote and following decades. The Conservancy has done much to call attention to the range of foliage of 20,000 trees whose foliage–Red Maple; Hickory; Sugar Maple; Scarlet Oak; Red Oak; Dogwood; Star Magnolia;–it keyed with classificatory precision–

–to bring the space into crisper detail for us, and to attract us into its surrogate of the greater wild.

An abbreviated catalogue of a parade of urban trees–“”Maple, oak, polar, gingko/New Leaves, “new green” on a rock ledge“–are the starting points for Snyder’s urban walk on the. bedrock in Walking the New York City Bedrock (1987) that capture their dissonance with the “gridlock of structures,/ Vibrating with helicopters,” in an ecosystem populated by businessmen or by “Cadres of educated youth in chic costume,” coursing in the subways and paved surfaces under which run subways, the lichen or spiderwebs of the urban ecosystem. But the restoration of the wild within the built environment of the city are celebrated in the recent atlas of the parks trees. For they have been allowed to congregate as an interruption of the built environment, but also as an ecosystem in it.

The “park” was long promoted as the primary shared green space in the city–and a space where city-dwellers retreat, at times, to smoke some green stuff in a meadow or on a hill, the definition of the park as a set of individual trees has rarely been mapped in detail, examining the arboreal space that inheres within this interruption of the built environment–if only to excavate and explore its complex past. For Central Park was built as a site of public promenades, a planned space akin to the popularity of the mid-nineteenth century Garden Cemetery movement that had led to the landscaping of urban areas as tranquil grounds of rest, designed within the city as sites of visitation and at a contrast from its commerce.

Walt Whitman, when a newspaperman, often entertained readers by the pleasures of knolls, rivers, and trees in faux rural Greenwood Cemetery that provided the illustration of Garden Cemetery in New York City by 1854, whose paths provided a sense of prospect over the harbor and winding paths, lakes, and hills among its monuments, that he inimitably exhorted all to visit, a combination of cultivated plants and open space John Bachmann crafted a perspective view in a tinted lithograph, inviting viewers to survey its planted trees and cultivated plants, as well as plains of grass and planted fields–

Library of Congress

–that encouraged the viewer to detect the cultivated scenery of trees and plants as if to recall the praise of Virgil’s ancient Georgics to agricultural cultivation of a bucolic preserve where “in the woods the almond/Lavishly blooms so that her boughs bend low,/Fragrant with blossom,” beside where “the crops will be/Lavishly rich as well, with the great heat/Of the great exultant threshing following on.” Amidst trees burgeoning with leaves, “and therefore over-copiously shady,” the park as the cemetery would offer a place of rest, as much as work, where “Among the cultivated plants/Darnel and tares and sterile oat-grass thrive,” the overgrowth cut back with pruning knife to nurture and reveal a well-tended oak tree, juniper, cypress, spruce, willow, Linden, beech, almond, following proper precepts of cultivation to reap the benefits of sewn seeds in the properly tended imperial landscape.

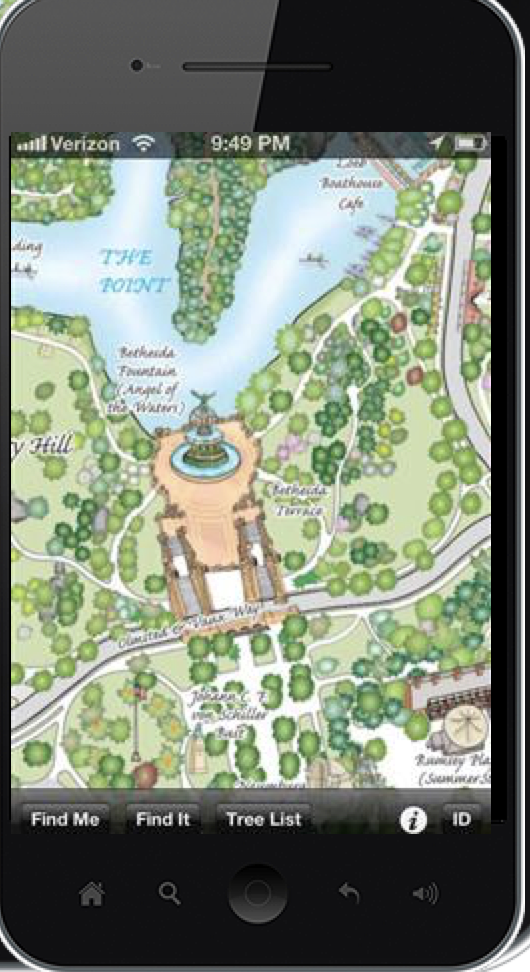

If Virgil’s paeon to the benefits of agricultural labors of planting, binding, threshing, plowing, and tending are recapitulated in the precepts of harvesting and care for the land to present a rich visual landscape in which the reader is immersed to enjoy its benefits, the range of trees, both planted and arriving by chance, have since created a landscape to be decoded by the map of each tree that the park currently contained. Drawn by hand in laborious attention to each detail, but now available as an app for easy assistance in navigating the park, the green monochrome of many maps springs to life in lists and individual detail, so that one is able to pan and zoom close-up on trees while one is navigating it.

The range of trees that now fill Central Park have been mapped by Ken Chaya and Edward Sibley Barnard in Central Park Entire, a detailed poetic catalogue that itself presses thresholds of cartographic creativity, individuating tangled ecosystems of planted trees, forested areas, native plants, evergreens and new arrivals that are mixed within its landscape, moving easily to a “tree list” that provides an easy way of orienting oneself to the multiple species inhabiting Central Park, allowing users to scroll, pinch, and zoom into individual regions and, when geolocation is enabled, to be oriented to wherever you are. Users can find the names of each of the 20,000 trees in the Park, based on Ken Chaya’s two years of surveying each tree in the park’s hundred and seventy arboreal species.

Even if the landscape was built on granite and was defined by concrete and brick, the trees defined its space, however paradoxically, in ways that capture the serendipitous presence of the arboreal variety in the city “Maple, oak, poplar, gingko,” ecopoet Gary Snyder mapped New York’s trees in syllabic feet, “New leaves, “new green” on a rock ledge,” taking the arboreal collage on Manhattan’s bedrock as a metaphorical ecosystem, an artificial reef of the human scheme of the “Sea of Information” filled with streams of “keen-eyed people,” “cadres of educated youth,” howling sirens, and squirrels, that peregrines sail above, whose gridlock opens like a sea anemone of which wind sends a shudder that “shakes the limbs on the/planted trees” beside “Glass, aluminum, aggregate gravel,/Iron. Stainless steel.”

The poetics of these long lists of urban inhabitants survey an ecosystem in a new form of rhapsodic evocation of their heterogeneous admixture of natural and artificial between paved concrete urban spaces. If Virgil praised farmers, Snyder celebrates the varieties of urban trees and pavement encountered in “Walking the New York Bedrock in the Sea of Information” (1987)–an island whose gods are capitalists, where the lavish overgrowth of plate glass windows shine beside the gleams of white birch leaves, a built and natural congeries where culture and nature overlap.

A modern Whitman, Snyder embraced walled urban canyon walked by curb and traffic light, counting trees among built space seamlessly, from ginkgo trees of Gondwanaland or built bodies to the pictographs and petroglyphs of subways, beside cable and pipe, erasing any distinction of natural and artificial, as “beautiful buildings we float in, we feed in,/Foam, steel, and gray/Alive, in the Sea of Information.” Snyder’s metaphorical recasting of the urban ecology is an ecstatic wilderness, underpinned by a tabulation of trees that echoes, in contrast of the natural and the built city how Herman Melville described the city in mid-century exultantly as “belted round by wharves as Indian isles by coral reefs,” but naturalized the built walled canyons where sirens echo streets as a built landscape where urban trees and wildlife abound.

Continue reading