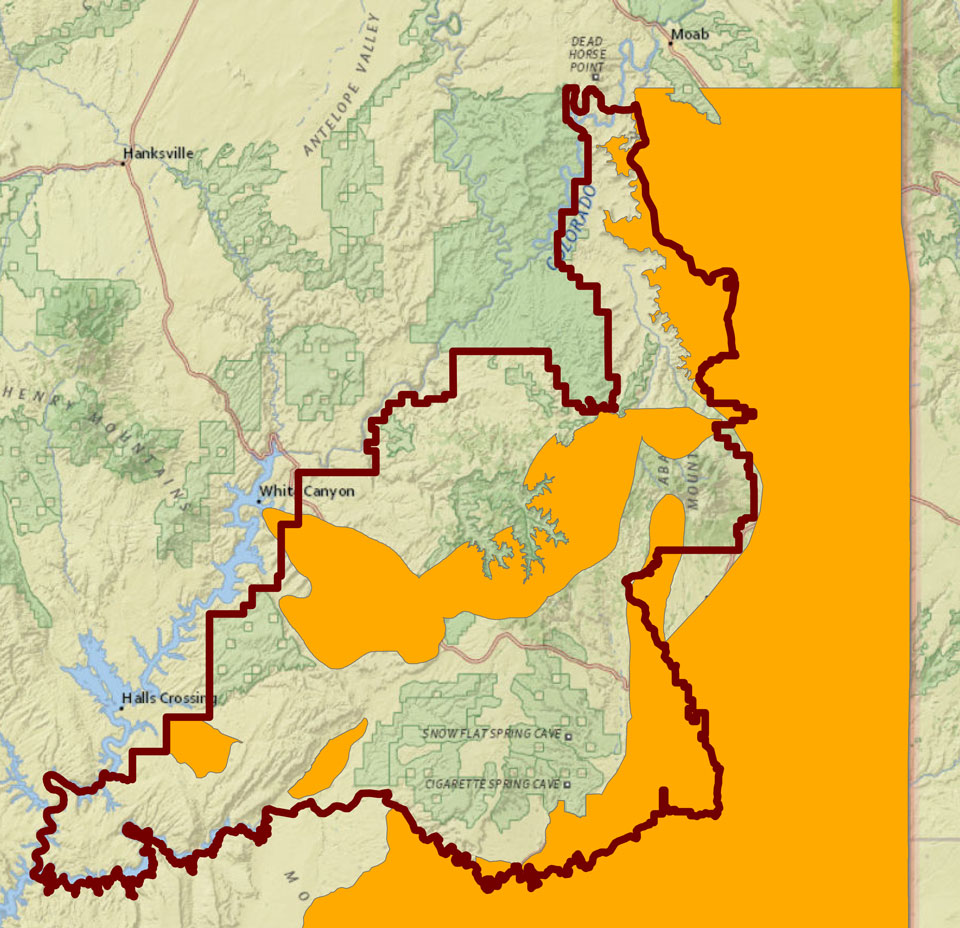

One must return to the value of the dynamic counter-map whose interactive form allows one to evaluate the curtailing of the monument not only as a way to expose access to mineral deposits in its once-protected landscape, but stand to permanently compromise the region’s cultural landscape in deeply disrespectful ways. The redrawing of the danger to Bears Ears mapped from leaked maps offers grounds to reflect on the absence of public engagement in the reduced monument, its relinquishment of public responsibility, and the near-eventuality of the loss of archeological ruins long historically sacred space as drilling, mining, and increased industrial traffic will obliterate the once pristine region as it is broken up and subdivided. Indeed, they allow the public involvement through the counter-mapping too the landscape that was being erased by the restriction of the protected region of Bears Ears, to reveal the density of its cultural landscape in ways that the integrity of the monument could be better mapped–and protected–provided a framework that helped mobilize support for the monument. While the landscape of land management was created to abut a National Park and land of the Navajo Nation, creating a puzzle piece to the future historic preservation of a rapidly vanishing west, the new boundary in fact suggests a landscape that would be quite vulnerable as it would be open to immediate threats of motor vehicles at its edges and Glen Canyon area, drilling and mining from Monticello to the San Juan river, and would leave much of the region unmanaged to prevent looting and grave-robbing.

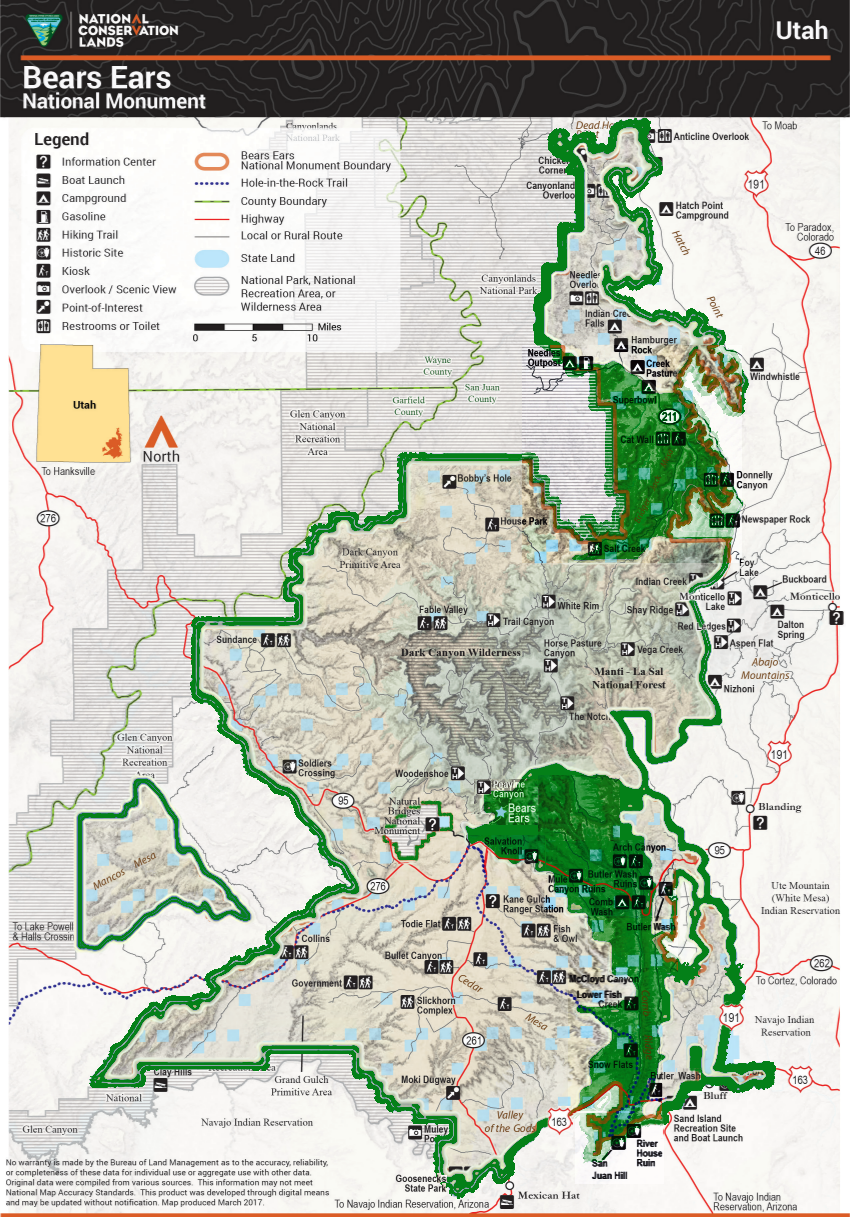

Click here for full interactive version of Maps for Good Map of Bear Ears

Click here for full interactive version of Maps for Good Map of Bear Ears

But the focus on this region–closely tied to the White Mesa uranium mill situated along the edge of the former National Monument, and near the White Mesa reservation, and Ute Mountain national lands, would be a piece not only of the map of mines in the region of sacred lands, but allow its development at the epicenter of a national trade in uranium milling from superfund sites across the nation–

–as well as the route of hauling uranium from mines in Utah across the former Bears Ears–as well as from multiple uranium mines a.com in the Grand Canyon National Park.

Although the region’s designation as a National Monument is repeatedly represented as “executive overreach” from Washington, D.C., and an abusive extension of federal power, the curtailment of the monument by a dramatic 85% suggests the redefinition of “value” and who determines the “value” of lands. The dramatic extent of the curtailment of the National Monument’s expanse is not only a act of bravado that stands to reduce the protection of public lands, but a definition of their value: the redrawn or, more euphemistically, “revised” boundary of Bears Ears, or, as it is proposed to be renamed, Indian Creek and Shásh Jaa’, a toponymic concession that takes the name of the entire stretch of land, sacred to native tribes, to refer to a vestige of the site. What Interior Secretary Zinke has called the “resizing” of Bear Ears opens the area to land grabs, and reveals, in a single executive order, a massive relinquishment of Presidential responsibilities: President Trump’s announcement to curtail the monument seems to convert it into real estate, echoing Zinke’s proposal to remap our national waters by renting rights to waters off of the Gulf of Mexico, or the Alaska Petroleum Reserve. The alignment of Trump’s America First doctrine of energy independence has been claimed to be a “defense” of local interests, unpacking the agendas of industrial lobbyists is not difficulty, if the extent of pernicious dangers has perhaps not been fully appreciated as an attack on the protection of and indeed the concept of the management of public lands.

Is the increased fungibility of federal lands in the Trump administration evidence of their transformation into leased properties or the Trump’s inclination to trade widely in debt? Is the value of lands parsed only by resources, or potential leasing revenues, or their use to extractive industries? The dramatic extent of the curtailment of the National Monument seems an act of bravado and a challenge to reduce the protection of public lands. For the radically reduced perimeters of the National Monument to two vestigial areas aggressively rewrote a process of the drawn out negotiations among local stakeholders–if excluding energy industries–to establish the monument out of United States Forest and land of the Bureau of Land Management, with the National Parks. The National Monument created significantly expanded the Utah Public Lands Initiative, a region local Senators who sought to transfer more protected lands to state ownership. The wars over public lands began with the radical reduction of how the former National Monument protected a region far closer to the proposal of an Inter-Tribal Coalition, in a complex of state lands, land from the US Forest Service, and yellow-hued lands of the Bureau of land Management,–absorbing lands the state long hoped to transfer from federal ownership, and which are now to be removed from federal oversight. While the proposed regions of the park mapped 1.35 million acres of federal land within its boundaries, a considerable reduction of the 1.9 million acres proposed by the Inter-Tribal Coalition, to boundaries that fit land management practices more easily than other local Public Land Initiative, the remapping seems to serve no interests save staked land claims of extractive industry.

The curtailed monument preserves a parcel impressive on the skyline from the road, rather than as a region whose historical meanings, untouched beauty, archeological and paleontological remains, and delicate ecosystem in fact part of the national patrimony of a disappearing west. The proposal to downsize the National Monument not only dismisses native claims to ancestral lands whose ruins that demand protection, but failed to adequately engage understandings of the lands, by substituting map layers of petroleum and mineral reserves over their expanse, blinding the government to their cultural and historical value as open space. Home to ancient cliff dwellings, sacred grounds, an immense wealth of archeological remains that are in danger of being plundered and looted, Bears Ears alone constitutes a rich historical patrimony erased by the underground mappings of its hidden mineral wealth. The American Antiquities Act passed in 1906 sought to preserve “any object of antiquity” or historical ruins on lands controlled by the U.S. Government; Trump seems to aim to betray his own custodial role as executive–and his role of preserving a national heritage–by opening these lands to for-profit speculation, in the name of securing an alleged “energy independence.” Indeed, the fragmentation of protected public lands that the reduced Bears Ears would create–

–replicates the utter absence of historical information in the timeless perspective of a GPS map, stripped of and cultural or historical relation to the terrain, or of its spiritual, archeological or cultural significance. Is it any surprise that the reconfiguration of the boundaries, described in faux disinterested corporate-speak as a “revision,” may have been managed within the soundproof “privacy booth” that the Trump administration created for the Environmental Protection Agency for Scott Pruitt at a cost of $25,000 in specially modified form to create the sort of “secured communications area” that seems a metaphor for the Trump administration’s relation to the nation?

Yet for the very reason that the paleontological, archeological, and artifacts in the region have not been included in a cultural resources inventory, including the Cedar Mesa, Dark Canyon Wilderness, and White Canyon, now removed from the proposed National Monument, whose mandate seems not to reflect the purpose of the Antiquities Act and whose shrunken boundaries were never fully or clearly explained–but mandated as a fait accompli, as if to hide the true motivations for the exclusion of 85% of the lands President Obama elected to protect as a monument of national significance, but Trump has been quick to demonize, with Utah property owners, as the first battleground, as Orrin Hatch put it, “in an escalating war over public lands” and an attempt to “right” perceived damages of a new era of federal land management.

Francisco Kjolseth/Salt Lake Tribune

Francisco Kjolseth/Salt Lake Tribune

Mason Cummings/The Wildlife Society

Mason Cummings/The Wildlife Society

For in opening access to the region’s underground mineral wealth–the “natural resources” that the Trump administration has come so short-sightedly, to prize with the same sort of righteous rhetoric of industry the the Reagan administration once adopted in loosening restrictions on offshore oil, they expose multiple ancient sites to disturbance. The Interior Department has recast protection of the ecosystem as a special interest, alien from the region. Looking at the landscape’s sudden reduction to four areass, one senses something other than the supervision of a delicate cultural patrimony or a system of adequate management of land–but rather a sort of shell game.

The buttes rise majestically across the horizon line, as imposing monuments. But suddenly stripped from their territory, and isolated from the landscape, they have been re-mapped by GPS as potential vestiges of a greater national monument, removed any sense of their context for the indigenous peoples who lived there after having been chased off traditional homelands. They are removed from the delicate environment that stands to be compromised by the arrival of extractive industries to whom the land stands to be leased, as they are invited access not only to current claims but to lease further lands for mining coal, uranium, zirconium, and drilling for oil, and indeed disrupting the earth that lies beneath the Mesa and in the ravines of the region, expanding the refineries and uranium plant that lies nearby.

Leaked Draft, Released by Wilderness Society, Downsizing Bears Ears Monument

1. The threat of the fragmentation of the National Monument to isolated “areas” of continued preservation is a remapping of their value to the nation that conceals vested interests: with over 40% of coal in America being mined on public lands, the moratorium on coal mining declared by President Obama’s Secretary of the Interior, as the American Energy Independence invites restoring hydraulic fracturing on public lands. This makes Bears Ears a sort of talisman of the opening of federal and public lands to a laundry list of oil industry interests as if they were identical with those of the nation or the residents of the region. It is no surprise that the new remapping of the region follows the maps that extractive industries had already defined. The compelling counter-map that Maps for Good allowed viewers to explore threats to the region in an interactive form reveals the scale of proposed land change: indeed, the density of the clustering of proposed uranium mines around the earlier national monument Bears Ears is shown against the expanse of existing parcels leased for oil and gas–noted in pink–and energy development zones in light purple, giving the lie to Ryan Zink’s statement of the absence of sites for mining in the National Monument’s former perimeter. By opening the land to extractive industries, as well as its dangers form looting, off-road vehicles, and unmanaged visitation of the fragile region, whose interests the boundary of the National Monument appears redrawn to accommodate–and allow access to multiple uranium mines near or in the boundaries of the former Bears Ears National Monument. The assembly of the map from linked maps procured by the Wilderness Society with Open Street Maps data provided a way of combating the truly predatory redesignation of lands that the Secretary of the Interior has tried to perform in a quite deceptive manner, without due process or public consultation, that seems to abuse the public trust.

Maps for Good/MapBox/OSM: Threats to Bears Ears

Maps for Good/MapBox/OSM: Threats to Bears Ears

The demotion of the region’s monumental status is not only a slight of two Democratic presidents’ aims to preserve the integrity of both the 1.3 million acres of Bears Ears and the Grand Staircase-Escalante into far smaller vestiges of a monument, and allowing access to existing mines ad oil wells. In creating two vastly reduced “monuments” out of 15% of the region, which were how re-named Shásh Jaa’ and Indian Creek, at a pen-stroke, evacuates President Obama’s decision to use the American Antiquities Act to preserve the region rich with historical ruins and its future integrity. While the Antiquities Act punishes any act appropriating lands designated such status without permission of the Secretary of the Interior, the remapping of lands as parcels that can be leased by government seems designed to grant extractive industries entry into the area in a single predatory fell swoop of his pen, using the executive order to foreclose the commons of the formerly open west for private interests. Despite the American Petroleum Institute’s recent calls to retire the Act, dismissed as the result of academic lobbying, the mandate for historical preservation needs to be redefined and expanded to include the endangerment of ecological fragility: indeed, paleontologists like David Polly, president of Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP), promptly announced suit of the Trump administration for failing to defend the unique fossil records on the lands. These are disregarded in maps of mineral resources which appear to have determined the reduced outlines of new “areas” of far smaller National Mini-Monuments. (Polly notes that the “two areas contain remarkable fossil records of important intervals of North America’s history, including segments that cannot be studied anywhere else;” a full twenty-five new species of dinosaur were excavated in the nearby Grand Staircase-Escalante, also greatly diminished in size by the Executive Order.)

Trump’s Executive Order aims to undo preservation of an array of archeological artifacts, rock art, natural monuments and forests announced between the Ute Tribe and Navajo tribal lands in southeastern Utah, in what was a coup in protecting the integrity of the historic lands. The ridiculously theatrical celebration of the ability that the Bureau of Land Management gained to lease the lands or parcels on it that was staged in Utah’s state capitol–

President Trump and County Commissioner Adams Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty

President Trump and County Commissioner Adams Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty

–as an absurd declaration of victory whose theatrical celebration, Trump raising his sharpie beside the Chairman of the San Juan County Commission raising his fist, seemed a mockery of the protection of the American west.

If intending to represent the local needs, Trump has hypocritically posed as defending from “outside bureaucrats,” flushed as if bemused by the fungibility of the lands previously protected by his predecessor. The local San Juan County Commissioner, long protective of their ability to invite industry into the lands, ludicrously wore a ten gallon cowboy hat to identify himself as a westerner, as Ryan Zink rode a horse to work the first day he was confirmed as Secretary of the Interior, channeling Theodore Roosevelt–the American President who had championed the Antiquities Act at the start of the previous century. The County Commission has long felt that they’ve over-accommodated native interests as well as environmentalists, and protected enough wilderness areas. President Trump seemed bemused by darn simple it was with a stroke of the pen to reward extractive industries with access to minerals and believed oil reserves.

But is their remapping not a historical coup in the influence of private industries, of a piece with the offers of the Bureau of Land Management of the largest number of leases to the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, the identification in October of “burdensome”regulations that prevent the exploitation of actual gas, petroleum, uranium, and coal reserves, that suggest, in keeping with the America First dogma, a notion of autochthonous economic development–a philosophy developed in Fascist Italy, and with a clearly anti-international genealogy–that prioritize the interests of the oil industries by revision of what the Secretary sees as “hampering the production or transmission of our domestic energy” and a failure to manage public lands “for the benefit of the people.” Despite the broad purview of “streamlining permitting and revising regulation” of the use of public lands and waters as a form of leadership, and not an abandonment of public trust.

Salt Lake Tribune/source: Oil Wells , Utah Department of Natural Resources, Oil, Gas, and Mining Division. Uranium & Mineral Deposits , Utah Geological Survey

2. The proposal to strip the lands of monumental status uses the false opposition of the governance and the administrations of public lands in ways that conceal that achievement, however, and blind us to their future losses. Despite posing as a defense of undefined “local interests” against intrusive government, repeating the Reagan-era anti-government mantra that they stand in opposition with one another, and deny the radical remapping of public lands that the Trump administration has decided to advocate. For the proposed rewriting of the national monument’s boundaries constitutes an undoing that cannot be seen as an adjustment of its perimeter, but a breaking up of its heart. The proposed monument encompassed not only archeological ruins and fragile ecosystem, but what had been alternately designated as a “special tar sands area” by the Bureau of Land Management, quite controversially, and had been promoted to locals as an “energy zone” at a time when many pristine environments–from particularly devastating areas in the coal mined in tar sands in the old-growth boreal forests in Alberta, whose devastation has been documented in aerial photographs of Canadian aerial photographer Louis Helbig,in images of the environmental degradation strip mining of bitumen brought to a once-pristine region.

Despite the promotion of a deceptive and very poorly defined “Energy Zone” in Utah, bordering the Bears Ears monument, that was suggested by the API, the assertion of economic benefits since 2015 within the American Petroleum Institute in Utah’s legislature conceals steep environmental risks of allowing extractive industries to enter the region. Indeed, given the laborious and uneconomical process of coal and uranium mining would create, the lifting of protections on the state and federal lands across the protected and ecologically delicate region- would compromise not only its National Conservation Areas but an invaluable archeological and cultural patrimony. Overturning the integrity of the region that the National Monument worked to keep by adopting the “new” boundaries would ensure open access to almost all the underground .mineral deposits in both National Monuments named by Democratic presidents in Utah, alerting the energy industry a new regime is in town, ready to allow opening up old uranium mines that encircled the Bears Ears regions when it was considered as a National Monument in the Obama administration.

Prosed Map for National Monument, by Stephanie Smith

In ways that have treated the strike of the pen of Donald J. Trump’s recent Executive Order as a fait accompli in the remapping of the once wild west, the Bureau of Land Management has reckoned the newly redrawn mini-monuments slated to replace the Bears Ears National Monument, as two lopped off areas, newly severed from their regional surroundings, in ways that reveal the pitifully curtailed areas that are prevented from being leased by the Bureau to private industries who are eager to extract the range of mineral deposits that underlies the region dense with historical archeological artificacts and spiritual significance. The local knowledge of the native tribes that have long settled the region was over-written not only by the United States government, but by executive fiat, without any process of consultation, in ways that raise pressing questions of the future of land management, the preservation of space, and the ecological intactness of the region. Unlike the multi-year process of crafting a consensual administration of public lands in the historical Public Lands Initiative, embraced by now-disgrace Utah Senator Jason Chaffetz, the circumventing of community interests has been revealed to follow the interests of multiple extractive industries–miners of veins of coal, old uranium mines, and possible oil deposits–that lie in lands already leased from BLM by industries, but whose arrival in the region with projects of strip mining and extraction were forestalled by the declaration of the region as a National Monument.

The compromised status of the vestiges that stand to be accorded the status of federally protected monuments indeed call into question what are the rights of locations or local inhabitants in the process of monument designation, now seemingly removed from a consensually crafted process to a caving into the vested interests of industry lobbyists who have determined with their own maps of natural resources to provide the template of what qualifies for recognition as a monument. Is it any coincidence that this has occurred in a Trump era, dominated by a President who spent most of his life interested primarily in projects of self-monumentalization in an urban area, who sees little need in ever visiting or setting foot in the two regions–Bears Ears and the Grand Staircase-Escalante Monument–that his predecessor and Bill Clinton had both declared. Downsizing the National Monuments–or demoting them as monuments–maps a huge betrayal of the public interest.

Bureau of Land Management (BLM) – Bears Ears National Monument

Bureau of Land Management (BLM) – Bears Ears National Monument

The radical rewriting of the national monument into conservation areas peels back the bridging of area around the buttes and the unique public lands arrangement that had been arrived at with local interests over time, but stands in contrast with the gold-tinged layer that the Utah legislature adopted, with few real reasons, but with the endorsement of the American Petroleum Institute, identified a poorly mapped “Energy Zone” colored a seductive gold on the east of Highway 191 to be “streamlined” for quick development–as if the gold could be readily found beneath its surface, and easily extracted, reminding us of just how easily maps lie and paper over interests–and of how strong the myth that “there’s gold in them thar hills” can still under-write a relation to space.

San Juan County Energy Development Zone against the original bounds of Bears Ears

The gold layer is not transparently scientific but impose a golden layer atop a topographic survey as a counterweight to the Public Lands Initiative that advocated the creation of Bears Ears. If the Initiative approved by a supermajority of residents with the twenty-five native tribes whose deep ancestral relation to the land, the “Energy Zone” was something of a conscious reference to the mapping of a new “Gold Country,” apparent to all if one could only excavate the earth, and presented in 1849 as “the El Dorado of the gold mines,” promised to contain gold nearly as high quality than United States coin in ways verified by the United States Mint–in order to similarly superimpose the lure of economic interests in a layer atop the region’s map, in ways that suggest how economic interests of the concealed underground can trump the accuracy and all other meaning in the map. In ways eerily comparable to the mapping of the California Gold Rush in magnifying the immediate gain over both the inaccessibility of the region and the long-term costs of the operations, cartographic creation of imagined geographic “Gold Regions” during the Gold Rush. The notion that such regions partly lay within the boundaries of the then-proposed national monument suggested a compelling lure, designed to be displayed to attract interest and entice miners to fix a destination in their minds in terms so powerful to trigger transcontinental migration. The designation of the gold hidden in the Sierra mountains–and offered potential routes of arrival from other parts of the world to prospect the gold that was hidden beneath the ground–could be a model for the compelling maps of areas that Petroleum Institute lobbyists convinced the Utah legislature to designate an “energy zone” where environmental regulations could be “streamlined” for reasons of the promise of future economic development, even if it would potentially compromise the natural landscape in regions surrounding or within the proposed monument back in 2015.

“Map of the Gold Regions of California, Showing the Routes via Chagres and Panama, Cape Horn, &c.” (1849) (Courtesy Ramsey Associates)

Detail of above: Gold Country and Great Interior Basin

Detail of above: Gold Country and Great Interior Basin

3. Is the curtailed national monument a similar counter-mapping, now endorsed by the government responsible for representing the stewardship of the land? Or does it openly betray them, by following a map to advance short-term personal and corporate interests, against the public good? The deeply suspicious suggestion of the promise of such an “Energy Zone” seems to update the promise of “god in them thar hills,” and to eclipse a democratic process of local land managment. By “streamlining energy development” in southeastern Utah, without any vision of costs or consequences of such development for the land, it erases a region not only among the most pristine in the west but densest with memory. Is this a step in the war against the memories of the relation to the land?

The hope to imagine the preservation of a region whose canyons, ridges, mesa and basins are rich with artifacts was evident in the proposal to create a counterpart to Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, created by President Bill Clinton in 1996, the current proposed curtailment by GPS clips a historical landscape to two vestiges of what have become highly politicized federal lands. Yet the currently proposed fragmentation of what seemed a groundbreaking advance in the management of native lands–joining members from five tribes with members of the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, and U.S. Forest Service, to recognize its identity as tribal lands and relation to a National Park–rejects a notion of land stewardship by resurrecting a battle between ‘locals’ and ‘big government.’ The “fake news” of such a loss of local interests would stand to permanently reconfigure the pristine open lands around the Four Corners region of the nation, in ways unable to be measured by the size of the original Monument, in ways disguised by debates about its boundary line.

If all of these lands are–and will be–federal lands, the opening of these lands to federal leasing is what is at stake by the removing designation of the National Monuments, which would expose them to extractive industries. As the new boundaries of the Grand Staircase-Escalante leave all coal in the region open to strip mining and extraction, and allow easier access to those areas lying just beyond the National Monument, the scaling back of both monuments seem to respond to directives of corporate lobbyists, from a uranium processing mill that sits outside Bears Ears to the American Petroleum Institute, representing firms who have purchased leases on sites within the monuments’ boundaries from the Bureau of Land Management, which did not evacuate them after the national monument was declared. The premium that the American Petroleum Institute places on the need to “recognize the importance of our nation’s energy infrastructure by restoring the rule of law in the permitting process” in the words of its CEO and President, Jack Gerard, prioritizes interests that were not addressed in hopes to rewrite the Bears Ears cultural landscape, and evacuate the conclusions of the local Public Lands Initiative (PLI) that resolved the many stakeholders’ interests in the pristine lands–and in the future of one of the largest open spaces in the American west. By recasting the monument’s creation as an act of “big government” that infringes on the land rights of local residents, the Secretary of the Interior has adopted the points of interest defined by extractive industries–the promise of oil; $11.4 billion tons of coal; and unspecified amounts of zirconium and uranium in the northeastern region of the Staircase Escalante–without the consultation of local tribes who hold the ancestral lands sacred, or indeed local communities. Indeed, the remapping of the region erases their historical significance, which it wipes from the map.

It is worse than a give-away, as their extraction would irreparably ruin the area under which they lie, if the quality of such deposits is often poor, and whose promise seems to have been magnified and poorly balanced against the costs of their extraction and the industries, pollution, and indeed toxic waste that this would bring to the region that seems likely to be converted to a Superfund site. Indeed, the proposed dismemberment of Bears Ears reveals a struggle between two forms of mapping of the region. One map attends to the cultural landscape and local ruins; the other privileges the “energy zone”introduced in the Utah legislature in 2015–and proposed by the American Petroleum Institute, who first vigorously called for reviewing the Antiquities Act to prevent its abuse for political ends. While posing as the “local interests” of the region, they have advocated exploration and leasing of the 105,000 acres along the eastern edge of the monument already claimed for prospective leasing by extractive industries–since 2013, claims that run across the designated National Monument, and whose leasing and examination would bring the construction of roads, equipment, rigs, industrial workers, and mining plants on the border of the current National Monument–and have already been auctioned to firms like Hoover & Stacy and Kirkwood Oil and Gas, per public record, or other energy firms like Energy Fuel Resources (USA), whose Canadian COO Mark Chalmers cautioned the Interior Secretary this past May 25 letter that preserving the 1.35 million acre region would compromise the nearby uranium mill operations.

Does the curtailed monument more closely correspond to outside vested interests, and betray the governmental and representational function of the nation’s government? Indeed, the continued interest that extractive industries have raised to the Utah Bureau of Land Management to lease 105,000 acres lying in or immediately proximate tot he current National Monument–and which encouraged its designation–the leases to some 88 have been reactivated by ending Bears Ears’ status as a national monument.

\

K. Clauser, Center for Biological Diversity (as of 8/28/2017)/Inside Energy

K. Clauser, Center for Biological Diversity (as of 8/28/2017)/Inside Energy

Bears Ears National Monument Boundary Modification – DOI.gov, The restriction of the former National Monument removes Blanding from federal protection

Bears Ears National Monument Boundary Modification – DOI.gov, The restriction of the former National Monument removes Blanding from federal protection

Such claims in line with Donald Trump’s America First Energy policy–and the promise of energy self-sufficiency–seem to mask the private value that are at stake in exposing public lands to the mining of uranium, zirconium, and coal. Indeed, the underground presence in the region of “precious natural minerals” seems to blind the Trump administration to preserving the cultural value of the monument. During Trump’s recent public appearance to sign the Executive Order in Utah’s state capital, he pointedly didn’t visit the land: the slightly coded reference to claims of the company running the last uranium mill in the United States bordering the monument, Energy Fuel Resources, who have also targeted uranium reserves in the Grand Canyon region. (Fuel Resources have tried to reopen sites in the Grand Canyon that they earlier ran, prevented in courts by the Havasupai tribe who have organized a campaign to stop mining in the Canyon. Work on the mine came to a halt again in March when the site began filling with water.) Although Grand Canyon Trust has been concerned of possible pollution of aquifers from existing uranium mines by the same company, which failed to test the quality of water near its mines, the poor history of stewardship of lands raise questions of the similar contamination of the San Juan and Colorado Rivers bordering Navajo lands–as the mining would open the landscape of Bears Ears to levels pollution not only hypothetical, but evident in the landscape of the unregulated mining of uranium has already created the Grand Canyon.

Caution Sign noting Radiation Zone near the Grand Canyon National Monument

Indeed, is it any coincidence that extractive industries of mining and mineral deposits specialize in a quite different form of subterranean mapping, isolating unseen underground wealth from a landscape while spending less attention to visible markers or history? The Bears Ears uranium deposits–a subject now on Trump’s mind, perhaps, if for the wrong reasons–have made the monument appealing site to allow extractive industries now prevented from working on National Monuments, many of whom have already staked claims in prospecting maps of what is cast in code words as “valuable energy and mineral resources.” But is the leasing of federal lands–whose monumental value is evident in the unprecedented wealth of archeological ruins and old-growth forest an the start of the San Juan river–able to be sacrificed for what lies underground? Or is it that the mapping of the underground minerals have somehow, in a circuitously evil fashion, come to replace the image of the lands before our eyes?

If so, the costs of such a substitution are not only high, but suggest a massive act of deception and abuse of public trust on the scale of which we haven’t seen for some time.

Salt Lake Tribune/source: Oil Wells , Utah Department of Natural Resources, Oil, Gas, and Mining Division. Uranium & Mineral Deposits , Utah Geological Survey

Daniel, you should send this to the New York Times Opinion editors.

Cheryl Koehler / Edible East Bay

Subscribe online at http://www.edibleeastbay.com Sign up for our e-newsletter here: http://eepurl.com/z-fkn Visit our advertisers to find your complimentary copy: http://edibleeastbay.com/find-a-copy

>

It seems on the long side, but thanks! Please feel free to circulate, Cheryl