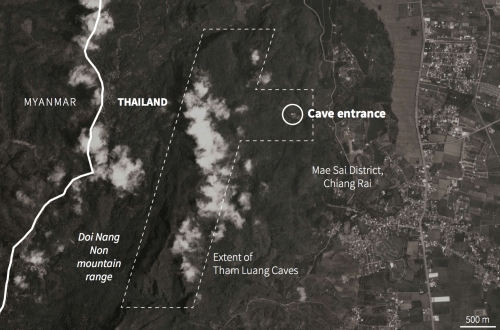

We followed with intense interest and hope the gripping story of the teenage soccer team who had entered the dangerous complex of narrow caves in North Thailand. We focussed on the possibilities for their rescue as we watched the narrow entry ways into the remote complex where they were stranded on rocky shoals, over two miles into the Tham Luang complex and over a mile underground. Before the maps of the narrowing cave, we could only imagine the excitement of their entrance into the cavernous passage where they left bikes, and to imagine the conditions where the U-16 team waited with their committed Assistant Coach, as we tried to get our heads around the dangers the team faced in the darkness, licking water from its walls over two weeks.

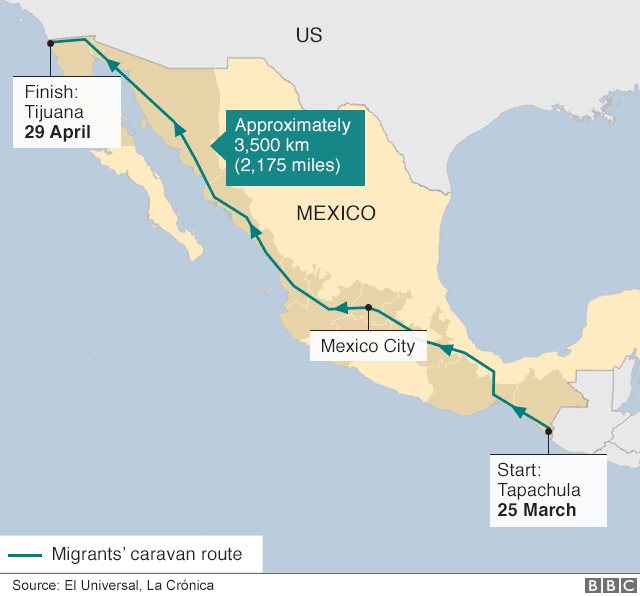

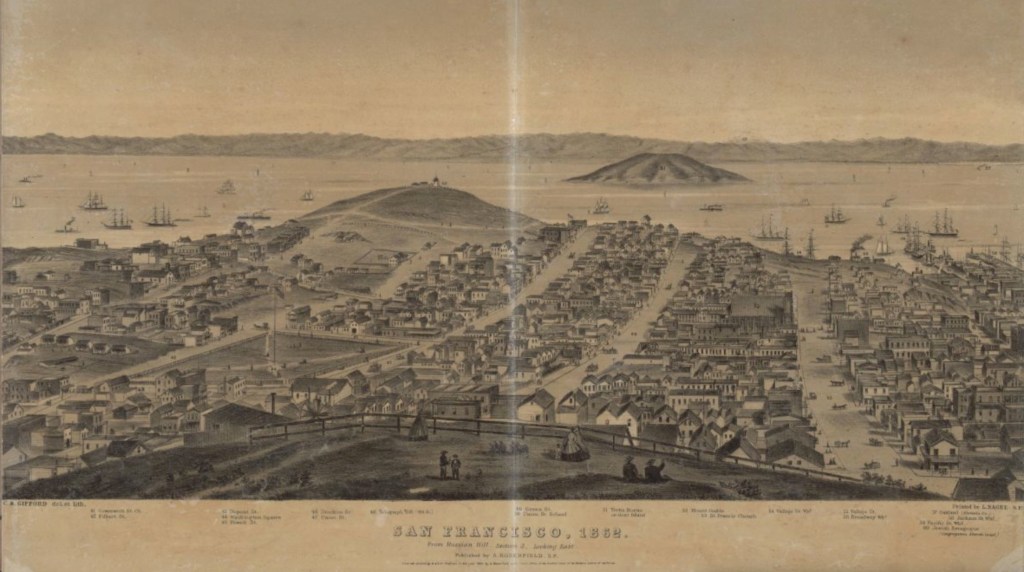

The deeply compelling story of the “lost” team attracted the global attention from their sudden disappearance, discovery by two divers, to their rescue gained huge interest and dramatic power, as we tried to move into the narrow confines of the cave themselves. Despite the immense power of the human story, and the endurance of each team member of the Moo Pah, or “Wild Boars,” the global scale of attempts to locate the team so remotely stranded were as historic, as we all tried to place the “Lost Thai Cave Boys”–all of whom nineteen divers have now thankfully rescued or extracted from the torturously narrow cave, whose cavernous opening narrows into one of the most labyrinthine of complexes of as one progresses into its passage ways. Lost both to sight, above ground tracking, and to global attention, the small group of soccer players compelled attention of the entire global media. The intense bond that existed for the team–who practiced with their coach who understood the sort of haven he was offering to them all too well–created the sense of solidarity that, in the end, trumped the dangers of being “lost” to a state or to public view.

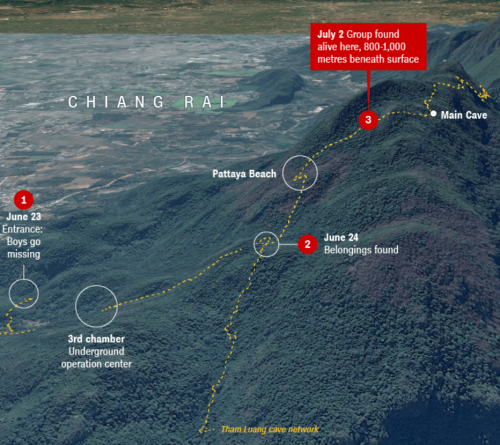

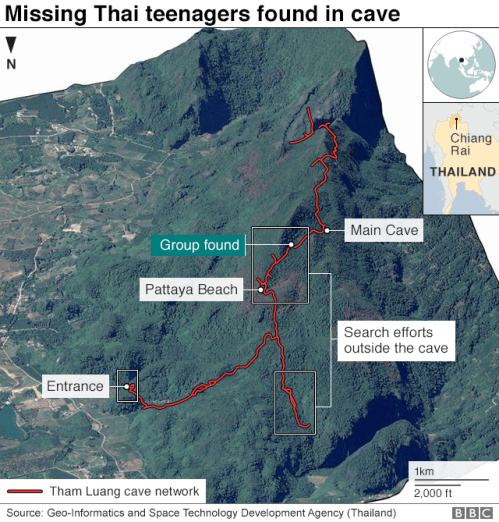

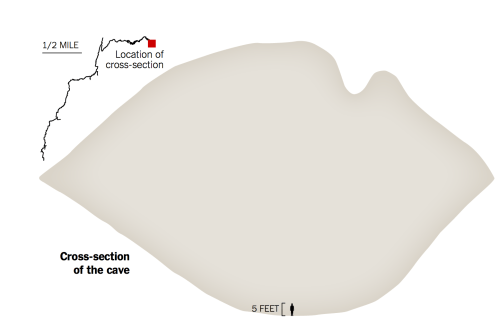

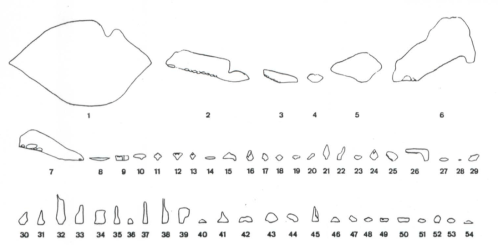

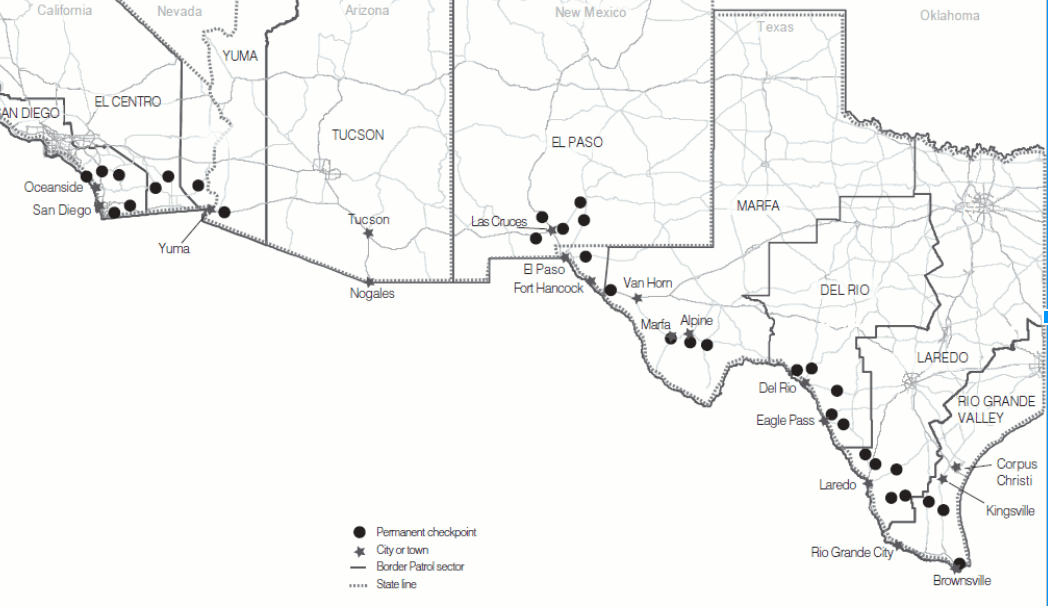

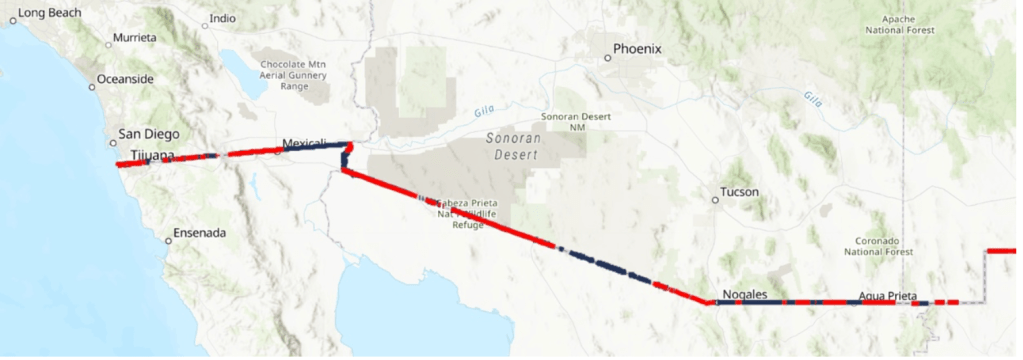

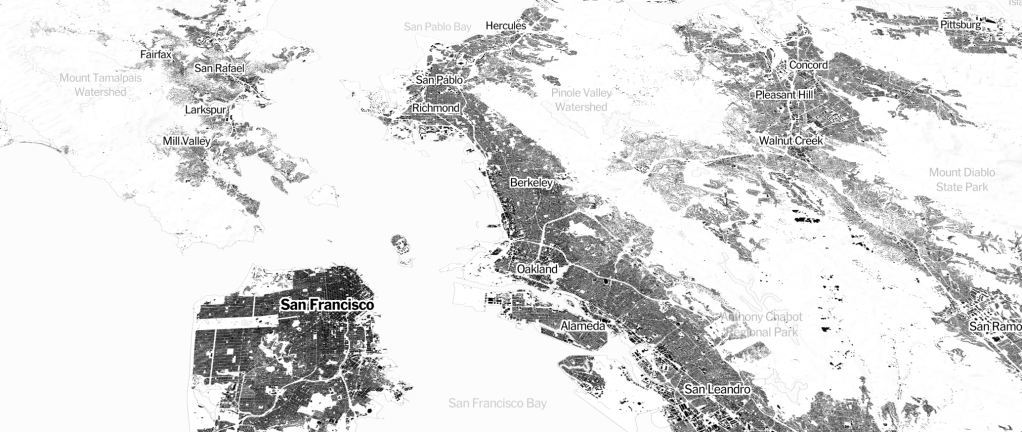

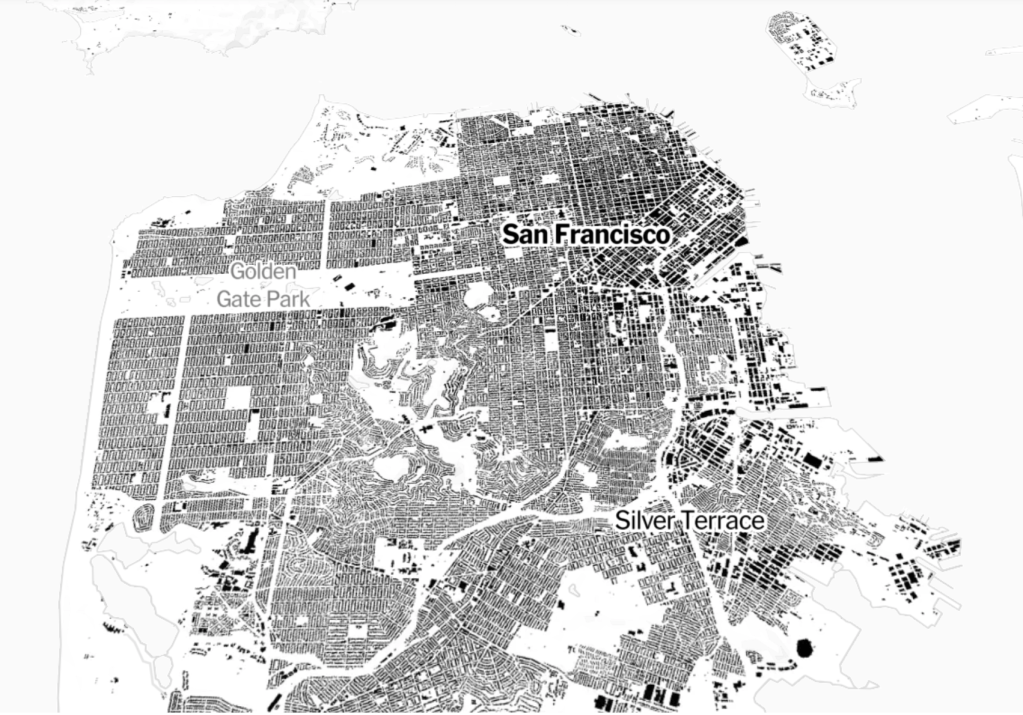

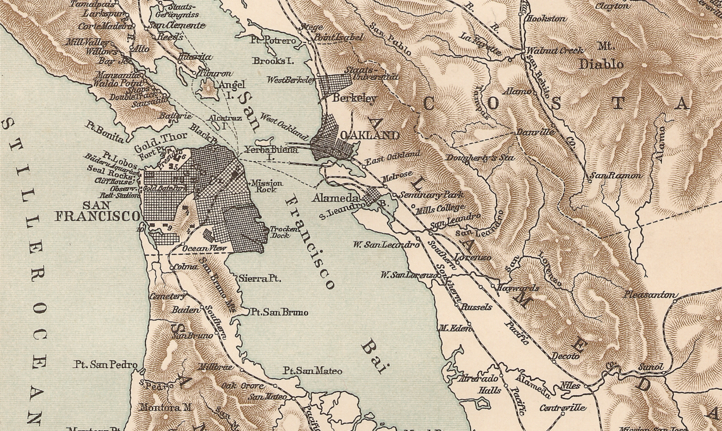

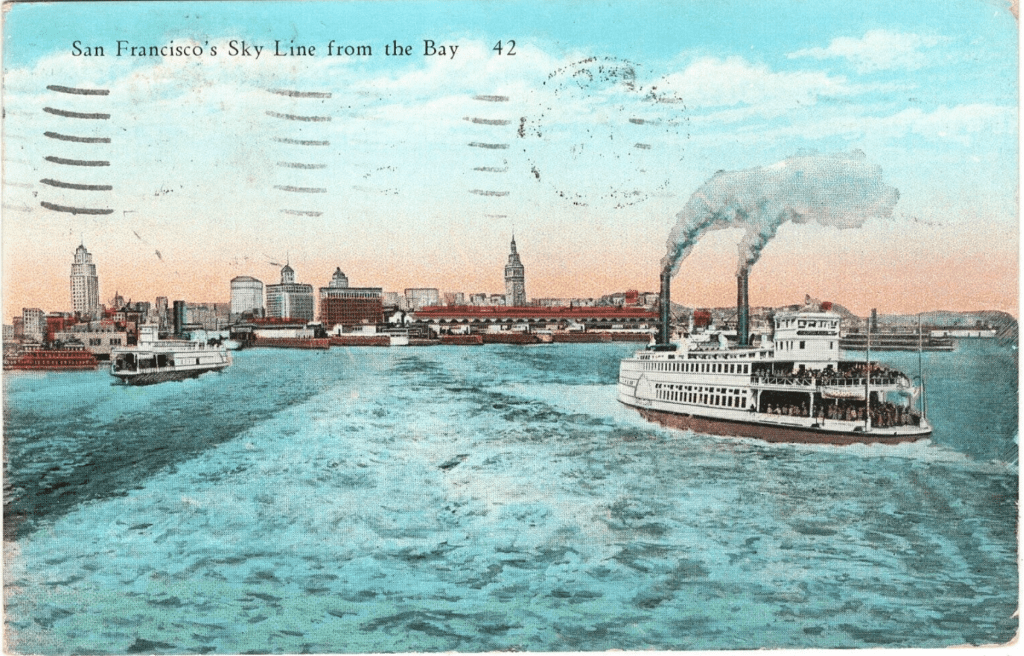

As they were lost to tracking, GPS, or other means of geolocation, the drama became one of the inability to map in an era when mapping technologies seem to have expanded throughout our lives. While the lack of GPS or wifi made navigation or consultation of instruments used in mapping of little value, cross-sections of the deep cave from forty years ago provided only the roughest of guides to the torturous paths of often slippery ground that threatened to fill from southwest monsoon rains–sudden rains already pressed the team deeper into the caves. As the teenage team was removed from all contact with the world, or abilities of geolocation, the rest of the world depended on maps to imagine the possibility of contact with the kids who were suddenly known, in a bizarre trending topic, as the ‘lost cave boys’ as if to foreground the increasingly uneven global distribution of technical expertise.

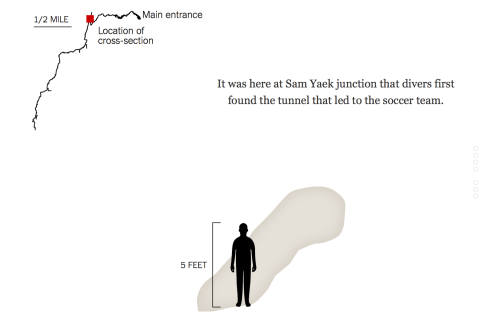

We needed maps to keep them in sight, as it were, and to imagine the very possibility of their survival: even the most schematic maps of the caves’ dimensions, abstract cross-sections drafted thirty years ago, offered a sense of contact with the team that was removed from GPS, so far removed to be out of contact, for over two weeks over a mile underground.

Tham Luang cross-sections, Association Pyrénéenne de Spéléologie, Expeditions Thai 87 – 88

Tham Luang cross-sections, Association Pyrénéenne de Spéléologie, Expeditions Thai 87 – 88

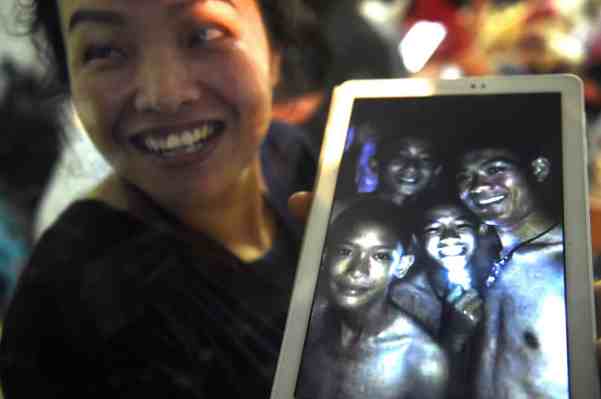

While the multi-national effort helped to guarantee the rescue effort was miraculous, it is also a testament to the sheer force of globalization that the former Buddhist monk who led twelve teenage soccer players–several of whom were stateless ethnic minors–became a compelling focus of international attention after being tragically trapped while exploring a cave complex. The young team, stranded two miles into a six-mile long complex, with limited food and air, were almost abandoned, until the surprising accidental discovery that the teenage members of the Moo Pa team–the “Wild Boars”–were all found alive with their Assistant Coach by a group of British underwater divers, apparently on holiday, exploring another branch of the vast flooded cave complex, who first photographed the team, smiling at having contact after ten days. If not for the fortuitous sighting and discovery–and perhaps if not for the lit photograph the divers managed to take of them in the cave’s depths, they may well have tragically perished. But what else is more emblematic of the globalization of the media than the ability to turn all attention to one spot in the world, that suddenly seems the only spot that cannot be otherwise mapped?

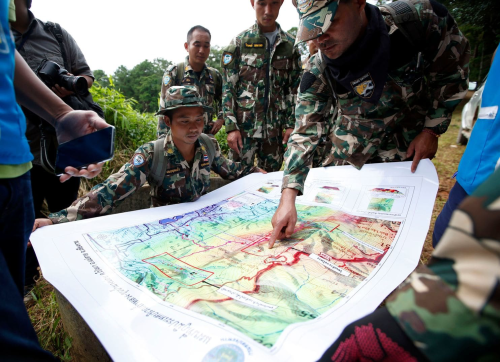

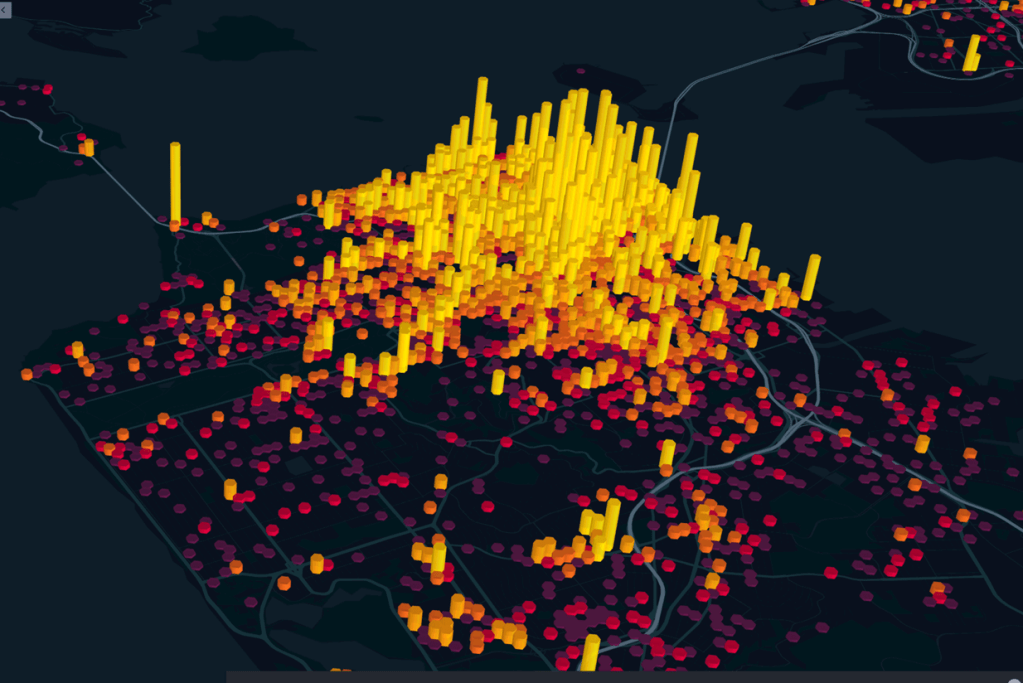

The happenstance discovery that was made a week and a half–ten full days–after the team members had after they disappeared was relayed around the globe, more a miracle of endurance as much as of modern technology, though the two were conflated. Able to capture them by cel phones, the image of their survival in the darkness underground survival mapped an odd snapshot of globalization. While the cave was visited several times by the Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, the statelessness of the players or assistant coach who helped found the Moo Pa team was not mentioned. As global attention turned to the cave, and divers arrive from the United States, Britain, Australia, Finland, and Canada, the search almost became almost a spectacle of state theater, as the Royal Thai Army undertook to map and track the location of the “lost cave boys” in the mountainous remote province, as global attention shifted to the Tham Luang caves, newly prominent in international headlines as an engrossing topic of social media.

June 28, 2018

June 28, 2018

July 7, 2018 (Rungroj Yongrit/EPA-EFE/Rex/Shutterstock)

July 7, 2018 (Rungroj Yongrit/EPA-EFE/Rex/Shutterstock)

The complex of caves in which the team members were stranded was abstracted from what was an area of widespread statelessness, divided between different warring factions, the possibilities of their rescue the focus of global attention. Such a heroic narrative was able to conclude, for one, in a far more satisfactory way than a focus on borderline events, or the fate of the stateless along the Thai border.

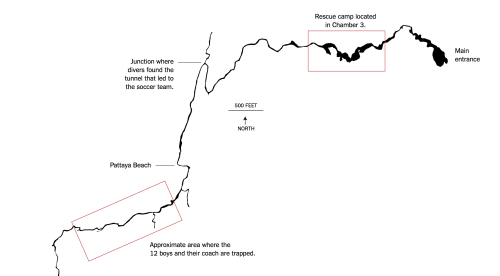

1. The efforts to discovery the team had already attracted help While U.S. Pacific Command had sent a rescue team to help in the search for the twelve players between twelve and sixteen and their coach, searching with Thai military using remotely operated underwater vehicles and heat-seeking drone, the absence of any indications in the complex Tham Luang Nang Non caves was puzzling. The mystery of their apparent disappearance was broken by an unexpected image of the smiling soccer team, on a ledge deep into the cavernous complex of caves, taking refuge from rising waters, far beyond the gear and cycles they deposited near its entrance, and indeed beyond the “beach” where those exploring this branch of the complex pause to rest, some four km into the cave. The flooded waters that had already begun to rise with the arrival of the monsoons that fill the cave annually, further imperiling the group. (The rains may have been a bit early this year, due to climate change.)

As the Thai army worked hard to locate the group for two weeks, the embodied problem of achieving the remote extraction of the soccer players focussed global attention; being trapped on a ledge in darkness by rising water when you don’t know how to swim was the stuff of universal nightmares. But the graphics of their rescue through the caves, now lit by lamps and accompanied by divers with head lamps and oxygen, provided a miraculous rescue narrative leading to their emergence.

Reuters, Hope for the 13 (January 9, 2018)

Reuters, Hope for the 13 (January 9, 2018)

The image of the smiling teens taken by British divers became something of a clarion call to expand technologies and tools for their rescue. While what is paramountly important is that the “Thai Cave Boys” are coming to light and to their families, even as the rains are beginning to fall heavily, the global spread of the news of their disappearance and accidental spotting and the massive media response that both triggered helped coordinate a rescue effort up to a thousand meters underground with oxygen tanks, headlights, a team of divers, ropes to allow steep uphill climbs of wet caves, once drained but in need of more pumping before monsoon rains intensify, and time for the team to take a crash course in diving; Dawn Cai successfully stitched together an elegant GIF of the trek to recovery that captures the confines of the remote cave, and the deeply embodied ways we all struggled to imagine the scenario we replayed in our minds, but this time casting the focus on the tools of rescue, from the position of rescue cable to the waiting helicopter and ambulances at the cave’s entrance to ferry the kids to safety.

The nail-biting drama of the survival of the boys for two weeks in the narrow Tham Luang Caves, two and a half miles deep into their interior and 800-1000 meters deep underground, attached global attention first as what a feared tragedy, resolved only with difficulty. What became a nail-biting drama of the “cave boys”‘ fate was the focus of global media; the gripping difficulties of the teenagers suddenly involved multiple states, directing more attention than ever to a remote cave in North Thailand.

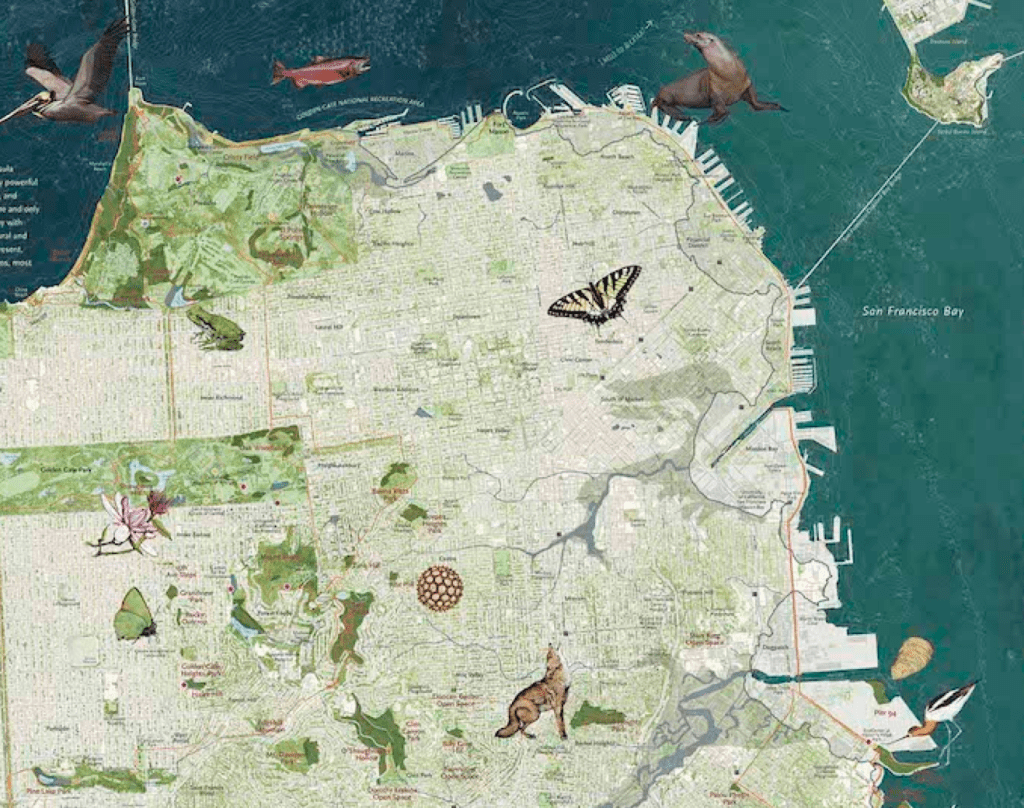

Looking at maps of the cave, the weird sense that we had in following the story that this could be a site anywhere–a cave that often seemed eerily disembodied from its environment or a specificity of place, or its location in the mountains near its border with Myanmar, site of thousands of the over 400,000 stateless refugees, displaced ethic minorities, stateless not yet granted asylum by Thailand, an area beset by drug trafficking, human trafficking, and malarial outbreaks. The relatively retrorgade region of the Golden Triangle divided between the Shan State North and South and United Wa–has become a site for high-tech mapping, however, as if to affirm the unity and control of a region divided by different local internal conflicts–and contested boundaries the had created refugee flows. The fact that it was normal for most children in the region to be stateless–as many of the soccer players were–made it all the more paradoxical and complex that the appellation of the team as “Thai”–and the involvement of the Thai military–were assigned a dominant role in mapping and locating the team in global media, as if the responsibility to track and locate them devolved around the nearest state to claim responsibility over the area–even if the players themselves lacked nationality. The

Asia Times (Chiang Rai province divided by United Wa and Shan state armies)

Asia Times (Chiang Rai province divided by United Wa and Shan state armies)

–which were determined the stories of the lives of the Assistant Coach and his charges. Ethnic strife was obscured by the tools of tracking the boys’ location and safety. The shift of global media attention to the lost boys seems to have led to efforts of the Thai Royal Army to create the impression that the team was safe–and the situation in Chiang Rai province controlled.

2. The first sightings of the team fed a range of credible attempts to locate and extract the twelve kids from deep in the cave, past a rocky shoal known as “Pattaya Beach” and through its narrow openings, was planned: we only had a sense of the depth of their location in the cave complex after the first sighting of the team that occurred ten days after their disappearance into the dark cave’s mouth.

Planet Labs

Planet Labs

Reuters, Hope for the 13 (January 9, 2018)

Reuters, Hope for the 13 (January 9, 2018)

The news of contact and communication made global headlines, and served to reorient global attention immediately to humanitarian offers to assist in rescue efforts in an age when humanitarian impulses appear globally in short supply; the image of twelve young members of the Moo Pah team, wearing brightly colored jerseys, on a perch on a rocky ledge deep underground, relayed around the world, seems a partial miracle of the ability to capture imagery in almost all places, as well as a reminder of the challenge of ever locating them on the map. If the terrifying nature of finding no response on your teen’s cell phone has long ceased to be purely a First World Problem, the alarm of loosing any contact with one’s teen seemed to foreground the terror of how quickly any trace of their presence had disappeared.

Despite the miracle rescue by which they were “found safe” inside the complex, as the monsoon rains were just about to begin, the mapping, and tracking the young Moo Pa team was a drama hard to get one’s head around that gripped the world, and lead to a huge exultation at the emergence of the first six players from the cave complex became a cause for global celebration, even as the former monk, the valiant Aekkopol Chanthawong who is their Assistant Coach, remains trapped with the rest of his charge and team, teaching them the virtues of stoicism and patience as well as techniques of breathing and meditation that had more than anything else to survive, presumably, kept them in good spirits and alive for over two weeks. Helped in part by the recession of the waters, but also by the shallow breathing techniques that allowed survival in an oxygen-depleted caves, the dedication of Aekkopol to the boys he trained not only in soccer, but to dwell in the dark stands out. The coach was practiced in long meditation retrains, and arrived as an orphan at the War Phra Thet Doi Wao monastery, only leaving training to be a monk after ten years. Where his own advice about meditation and calmness a crucial importance to reducing the team’s panic, as well as the trust he had gained?

(Is the broadcast of plans to ordain eleven of the boys as monks as novices and their coach as a monk occurred after their rescue, lighting candles at Wat Phra That Doi Wao monastery, consolidating and combining the international broadcast of their rescue with a traditional Buddhist coming of age ceremony?)

Wat Phra Tat Doi Wao monastery, Chiang Mae province in Golden Triangle

Wat Phra Tat Doi Wao monastery, Chiang Mae province in Golden Triangle

The techniques of meditation and focus that he used, no doubt developed on meditation retreats with little food or water in the forests surrounding the monastery, were obscured by the focus on the range of technologies that were imagined to perform a rescue operation able to bring the boys from the cave. While knowledge of the possibility of their rescue, the survival of the team fed their survival past ten days, their survival was the other story that was masked by the amassing of international efforts, helicopters, diving equipment and cables to find and extract members of the team from the cave complex, equipped with oxygen canisters and lights. What is celebrated as a high tech adventure rescue depends on the focus of the former monk who, despite his statelessness, has become something of a national hero–but also for the techniques of survival he imparted, more important than the anti-anxiety medications that the multinational team of divers brought when rescuing them.

The unfolding involvement of a global commitments to locate and extract the thirteen teens seems a modern counterpart to the myth of Princess Jao Mae Nan Nong who fled her parents with her love to the complex of caves after their forbidden love was discovered, and still serves as its protector. Princess Jao Mae was said to have stabbed herself in the complex of caves where she had fled her parents with her lover, after he was killed by soldiers her father sent in pursuit, and her blood forms the waters that fill the caves, providing a powerful link between the caves and the afterlife. The Princess’s spirit still is venerated as protecting those who enter the cave complex in the Mae Sai district of Chiang Rai province; indeed the altar of the pink-robed Princess after the boys disappeared attracted attracted many offerings, incense, and candles with other offerings as raining and flooding slowed the search, and her role as a powerful bridge between the living and the dead and guardian of the caves in northern Tahailand gained power as a focus for hope of intercession.

The story of the fate of the “lost boys” became a parallel tale of the turning of global attention turning to the caves in Northern Thailand, to provide a different form of intercession as rescue efforts grew The stories of Jao Mae shifted, to be sure, to new mapping technologies as the members of the team were located and found, as if in response to the efforts of collective prayer, and a variety of possible new schemes for locating and saving the lost team became a truly international affair, unexpectedly turning all attention to Northern Thailand for evidence of reasons to hope. To be sure, the rise of an emphasis on technologies of tracking and mapping the caves may have displaced the prominence of breathing techniques and meditation practices that played a large role in the Wild Boars’ team’s survival underground for ten days. “In the cave,” deep beneath the surface of the ground, as military soldiers combed the mountainside with maps, remembered the head coach Nopparat Khanthawong, the assistant coach had “taught the boys how to meditate so that they could pass the time without stress,” as they waited in the darkness, without food or any sense of the passage of time for ten days, in ways that “helped save their lives” by techniques learned asa novice fat Phra that doi wao temple where he arrived as a refugee orphan from Myanmar. Aekkopol often meditated with monks of the temple and the surrounding forest for days at a time with only a small reserve of food. And he was the last to leave the cave, shortly before the pumping apparatus that had drained the caves of rainwater failed. Yet the entire affair and rescue was shown and described most often as an instance of modernization, supervised by the Prime Minister, in which the Royal Thai Army played a major role in securing the area, developing strategic approaches, as well as draining the cave.

3. Tracking the site of the lost team had riveted global attention and indeed become a project of global mapping over the week plus since the tragedy of their June 20 disappearance unfolded in the news, from the first incredulous attempts to track their location in the torturous complex of underground caves to the more recent imagining of rescue attempts by diving, drilling, or any other means of extraction, as the under sixteen soccer team learned new techniques of breathing, meditation, and perseverance from their dedicated Assistant Coach. We collectively communed with them, and contemplated their chances for rescue as we south to orient ourselves to the unfolding development of what we didn’t want to imagine was another human tragedy through our maps. As we needed to believe they were alive–as they thankfully were–maps were an affirmation of their existence, and a logic of collective action.

Paper maps provided a surprisingly important point of reference above ground, as the position of the boys was considered and contemplated in previous days, as if to preserve or imagine a virtual tie to their remote location.

Pongmonat Tasiri/EPA

Pongmonat Tasiri/EPA

Despite the diminishing hopes of teenager’s survival after the first week they went missing, their survival of the children has become something of a test-case to find if there is any area of the world that cannot be mapped–and for rescue technologies, as well as a drama of locating hope underground in a darkening above-ground world. For global attention to the video taken by British divers of the group of teenagers who were trapped by unexpected rains while exploring the complex with their Assistant Coach after practice, and the possibilities of international cooperations to locate the small group was nourished on social media, if it had already electrified much of the nation. What was already a state concern of Thailand’s prime minister, Prayut Chan-O-Cha, the often unspoken if unseemly question of whether Thai soldiers and policemen had the necessary technology or skill to locate the lost team, as hope at their discovery gave way to fears of how to extract them from the cave, or return them through underwater passages,–either by drilling into the soil or squirreling them through often narrow caves. But the fears of altering the structure of caves were balanced with the difficulty of navigating within its dark, narrow passage-ways.

What became a local exercise that the boys to explore the cave complex that the rising of the waters suddenly trapped them became an international affair, as the the world wide web focussed global attention on images of their fate, as a grainy photograph of a few smiling team members on a tablet became a cause for unexpected jubilation and offered a sort of technological reassurance even as their fate was unclear. Images of relatives praying near the caves’ entrance with offerings of incense, garlands, and an eventual altar were balanced with images of high-tech mapping of the paths that the team took. The utter joy one parent showed at the arrival of the image of team members on a tablet triggered a global effort to locate and save the team members believed lost, who truly seem to have shown more resilience than the rest of the world. The sudden burst after the confirmation of their survival was a sort of miracle—they seemed healthy and even well-off while deep underground!–but the sense of a miracle was conflated with technology of the image relayed above ground.

The sudden alarm at loosing contact with one’s teen’s cell phone would have perhaps set off alarm world wide, even if the team was not found to be located at such a remote remove. Is it a coincidence that in an era when few children are encouraged to wander far from home, or explore their local ravines and neighborhoods without worry, that the attention of the world was turned on the team stranded in the cave? Most on the internet wondered what in God’s name the team was ever doing in the cave, or on the warning sign posted at its entrance cautioning about entering as monsoon rains approached. The flooding of the cave where the team members were stranded was glossed as a tragedy, a race against time, and as an international challenge for sustaining hope, as the former monk became a true hero, teaching his team techniques of shallow breathing, meditation, and focus with self-sacrifice that gave them strength and perseverance in the face of terrifying danger. He was the last to leave the cave, and soon after his departure the pumping apparatus that had drained the flooded caves broke.

Wat Phra That Doi Monastery, norhtern Thailand

Wat Phra That Doi Monastery, norhtern Thailand

The complex of caves in northern Thailand became something of a final site for nature, and struggling against natural forces, without wifi or GPS, even as the sense of why a team would go exploring the network alternated with worries rising waters complicated their rescue. As an international effort grew, as new technologies were mapped onto the essentially quite human, all too human effort to locate and save the under-sixteen team and its dedicated Assistant Coach beneath the mountainous terrain.

Hope transformed to preventing a terrible tragedy as possible rescue missions are contemplated or planned, and attempts to map their fate. The difficulties of their extraction riveted global viewers to the fate of teenagers hailing from borderlands of Myanmar and Thailand, who were chosen for their interest in soccer, as forces from the Thai Army to Elon Musk to the former Navy SEAL diver who died in doing so have tried to understand how to extract safely, in what a real-life drama that dramatically surpassed the World Cup, and offered a narrative of international cooperation to save the teenagers feared lost, who were themselves stateless, as their relatives continued to bring offerings to the Jao Mae shrine venerated as able to bridge the cave and otherworld. The story of the post-practice exploration of the complex by twelve U-16 teenagers aged twelve to sixteen–the age of my daughter–seems one of the technically difficult of situations processes, but most unfair as the story of a lost school group has grown as posted photographs of the twelve kids has provided a ray of hope, despite fears of future flooding of the caves by rains, and the perpetual threat of diminishing oxygen.

The complex’s narrow walls and rather torturous network provided what seemed the only remaining thread by which they could be saved or captured, and the specific difficulties of negotiating a rescue in the cave, after multiple divers had already tried to move along narrow passages to explore the caves, and unsuccessfully attempted to drain them with pumps, as the team was found farther into the complex–and up the hill–from where soldiers had earlier searched, and consideration of the place of Pattaya Beach–near where they were found, but in a delicate and narrow section of the caves.–and around the sections of the hill that soldiers examined above ground as they discussed the possible routes of their rescue.

4. While the cave entrance remained large fairly deep after its entrance, the problem of following and mapping the progress of the boys into its sections grew more concrete after it was discovered how deeply in they had travelled, just past the raised area known as Pettaya Beach. And so we turned to the most apparent exact records of the openings of the torturous cave complex where the team and their Assistant Coach were stranded, to imagine our proximity to them in a time of need.

Tracked by the latest mapping technologies and relayed on media circuits since the news of their discovery erupted, the plight of members of the Moo Pa Thai soccer team trapped in the six-mile long Tham Luang cave complex has been a focus of global attention and mapping efforts. The mapping and remapping of the site is of course both a testament to the dire nature of the situation of a group trapped deep within the cave, with limited oxygen, as well as food, buoyed by the miracle of their discovery after nine days and were stranded after they began exploring the cave and the difficulty of drilling from above-ground or navigating the dark cave itself to locate the team of teenagers trapped within, suffering the stuff of nightmares, as well as the problem of extorting them while negotiating narrow often underwater passage-ways. Despite their actual inaccuracy, the apparent exactitude of the cross-sections created an imagined tie to this otherwise multiply removed area of the world, neither satisfactory mapped or governed.

As rising waters threatened to fill the narrowest of cave walls, unable to accommodate air tanks, and attempts to pump water from the complex failed, mapping truly seemed the least of it as the extraction of the team faced the pressures of rising waters, malnourishment, and oxygen lack. (Elon Musk boosted hopes by tweeting his team was developing a narrow child-sized submarine pod able to navigate the hairpin turns in the cave complex, as if the pod would quite miraculously be able to be constructed and arrive on time–and even travelled himself to the cave system, seeking to promote the value of his oxygen engine to the Thai team.) The collective ensemble of efforts, spurred by the problems of locating a group of boys who didn’t know how to swim or dive as the waters ran into the cave complex, was a logical problem, in many ways, that demanded resolving problems of entering the cave underwater, illuminating the passage way, and guiding the boys out, as well, it seemed, as draining the water that had already entered from growing rains.

But the challenges of mapping their location, and the sense that they had traveled to a place so remote where they were not able to be mapped and tracked. The problem in part created a level of tension that riveted the world. The human drama of the young members of the Moo Pa team, became a subject nand symbol of national as much as provincial pride, as the problems of skills required to achieve their rescue became debated. The discussion and debate seemed a parallel story in itself, even if the possibly deadly adventure of the group of teens was intensely involving. The Thai Army that sought to ascertain routes of their rescue looked over maps of the cave’s veins that snaked under the mountain ranges, as if to plan the underground rescue–focussing on the cave complex they knew so well, but with less of a sense of how to extract the kids trapped within by drilling from above ground.

Rungroj Yongrit/EPA-EFE/Rex/Shutterstock

Rungroj Yongrit/EPA-EFE/Rex/Shutterstock

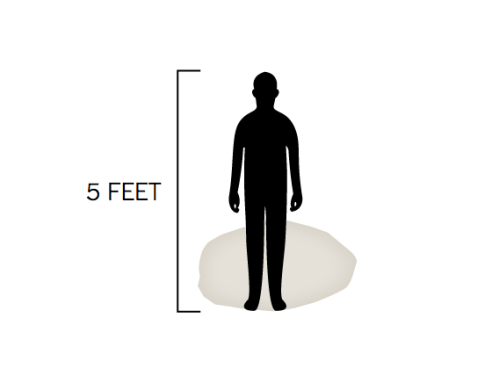

Despite the actual insufficiency of maps, we have tried to map the incredibly narrow contours of the cave complex, as if to puzzle over how they might be located and saved, and somehow track their course along the narrowing width of the complex from its opening–as if to map the difficulty of the job to the scale of a five-foot tall teen–to craft a more experiential record of speleological cross-sections of the mines through which the teens had traveled. based on the first surveys of the cave of 1987 of its narrowing cross-sections, now assembled in a more interactive form, as if in a flip-book–

–that helped to embody the experience of being trapped in such narrow confines so deep underground where they were trapped. The apparent accuracy of these speleological cross-sections was suddenly enlisted to create a sense of imaginary connections to the team whose fate we could not imagine, as if the insertion of a five-foot tall surrogate teenage icon helped capture the embodied experience of surviving in the cave and calibrate the difficulties of their rescue.

Images borrowed from the largely structural maps of cavers who had explored the narrow Tham Luang complex–and from the exact field of speleology–the visualization sought to pose the options for rescuing the team members in the narrow caves where they were stranded, learning how to negotiate with limited oxygen and rising water. The interactive map in the Taimes invites observers to imagine their narrowness, but minimized the complications of locating the team within the cave,–it elicited wonder at how the team had managed to climb so deeply into the complex as the water rose.

5. But the “map” reamined oddly abstracted form crucial information about the underground setting–failing to suggest the real problem of rising water and ground conditions, as while tracing the path of complex with accuracy, it strips a 2D sense of location from the context of rising waters and difficult ground conditions in a cave from which water needs to be pumped. But perhaps the point was to capture the compelling embodied experience of their in the remote cave. The Interactive graphics nicely reproduced the difficulties of moving along and negotiating the narrow turns, some requiring kneeling, swimming horizontally, or crouching to pass as if to experience the narrowing of its amazingly twisty course, as if in a video game, tracking the tortuously narrow course of the caves, through which the team progressed to try to avoid rising waters, in a nightmarish situation with all to real consequences.

But we were linked through the miracle of interactive mapping to pray for the futures of the teenagers, with their schoolmates and Buddhist monks who assembled at its entrance, as if to restore them to a map. Even as we cringed at the near-impossibility of establishing their location, after already one diver who attempted to locate them lost his life, contemplating the entrance into the narrowing passageways of the caves and the team’s itinerary as well as the possibilities of their future rescue.

Reuters, Hope for the 13 (January 9, 2018)

Reuters, Hope for the 13 (January 9, 2018)

While watching forecasts for raises that can boost the already rising floodwaters, teams of divers have contemplated maps, and the rescue camp locate near the mouth of the cave provided only a possible site of salvation, in hopes that they could be moved there. Is the cave’s mount a more apt site of prayer, or of recovery?

The misfortune of the soccer team had converted the mouth of the cave to the site of an altar that was sort of shrine, and a site of prayer for divine intervention, as worries turned to what thin, depleted oxygen the team members might still have access during the two weeks after they disappeared, their bicycles found, partly washed away, near the cave entrance, while the classmates of the team-members participated in large collective prayers, and Buddhist monks gathered near the Tham Luang caves, juxtaposing the science of mapping their location with a perhaps more credible collective prayer.

Were the major efforts in mapping not serving as their own sort of prayers, if of a modernist variety, and hopes for a miracle of intercession before the waters rose and the oxygen depleted in the stretch of the rocky cave complex? While the maps did show the human story of the position to which the teens had arrived, and posit and frame the problems of their rescue, thankfully underway, the maps seemed as important as framing, sustaining, and affirming a sort of tenuous empathy to their fate, allowing access to the remote cave system. If they created the possibility of the necessary conditions for their rescue they also became a kind of guiding light for those of us who followed the spectacle so intensely from our own backlit screens.

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc (New York City, Federal Plaza, 1981-89)

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc (New York City, Federal Plaza, 1981-89)

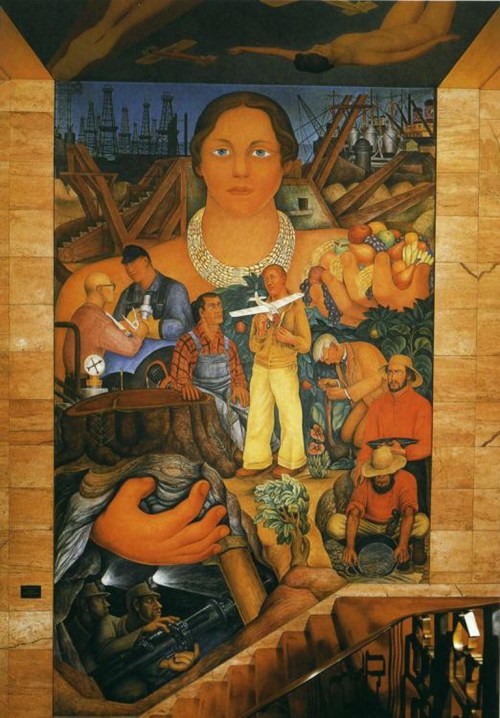

Jose Orozco,

Jose Orozco,

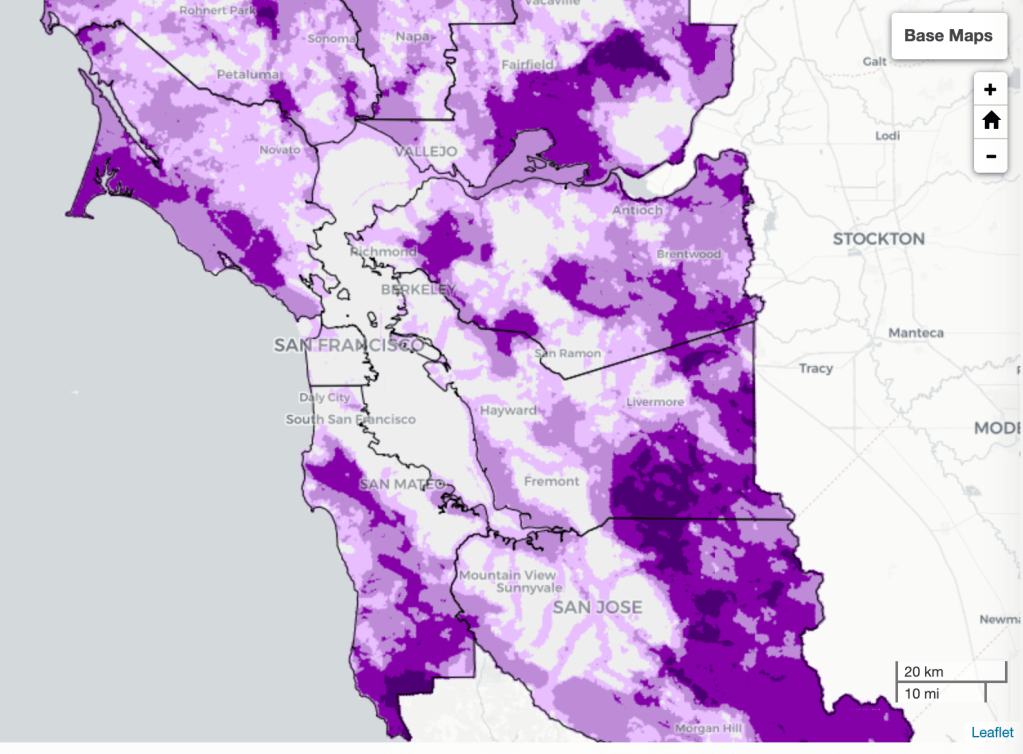

Google Maps

Google Maps

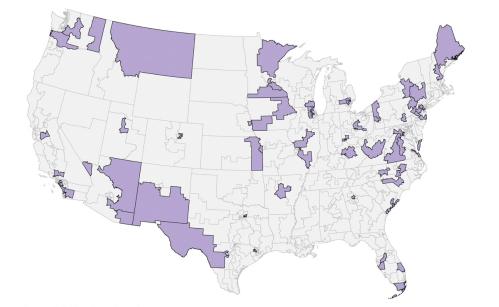

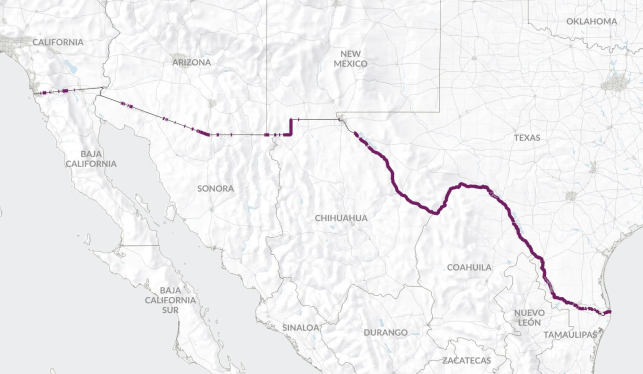

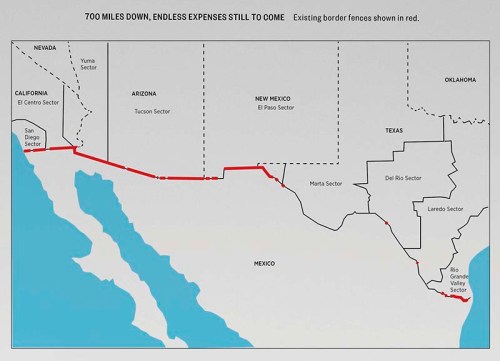

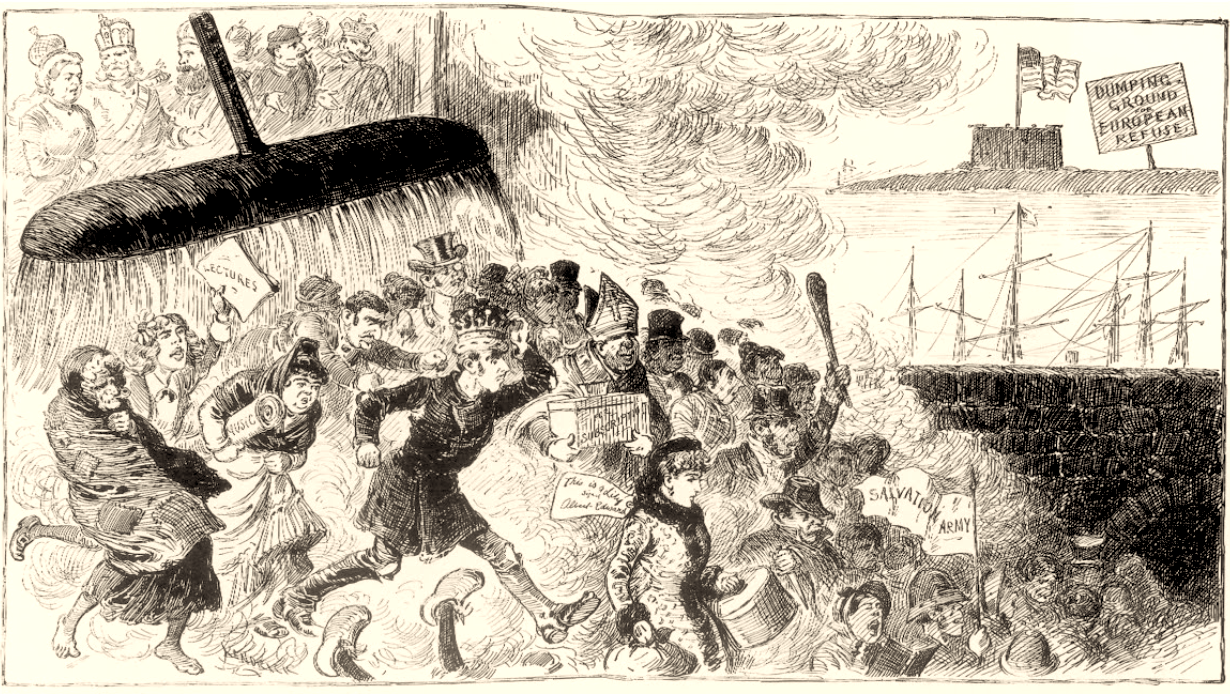

Kendrick, “And We Open Our Arms to Them”

Kendrick, “And We Open Our Arms to Them”  ICE Arrests of undocumented immigrants, 2014

ICE Arrests of undocumented immigrants, 2014

Video grab from RU-RTR Russian television (via AP), Thursday, March 1, 2018, allegedly portraying Russia’s firing of a nuclear-powered intercontinental missile

Video grab from RU-RTR Russian television (via AP), Thursday, March 1, 2018, allegedly portraying Russia’s firing of a nuclear-powered intercontinental missile