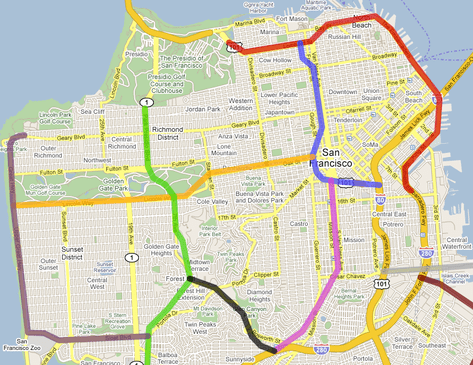

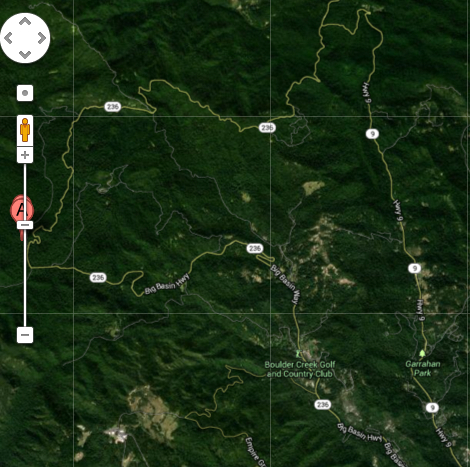

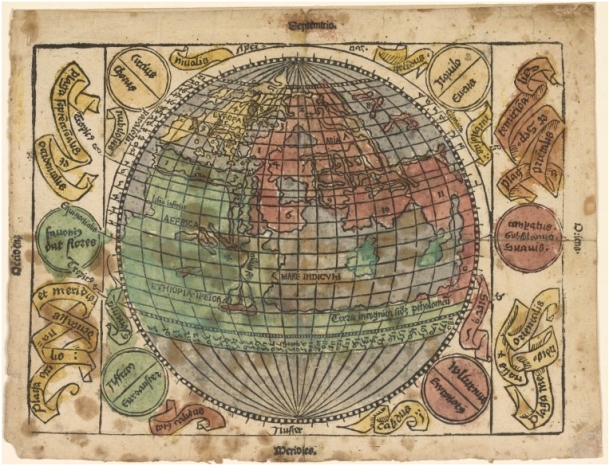

Data visualizations often employ maps to make their point, and organize an effective argument that will engage their audience: when we see data embodied in a map, and are best engaged in its interpretation. The alchemy of the data visualization is a magic way to throw the map’s content into multiple dimensions: data visualizations offer plastic forms of mapping to illustrate the way we fill and occupy space, transforming the mechanics of mapping specifically intended to track the stability (and meaning) of constructions of place, and orient us to different perspectives on how we move through space. We can better understand the ways links can be drawn about data in clear synoptic terms, and reassured by the act of discovering new patterns in a readily recognizable form. In describing the spatial distribution of an attitude or affinity, maps are readily consumed. But they are also cognitive tools to process shifting notions of place: the sleek tapering negative lines in the above visualization of San Francisco’s cab traffic offers a dynamic model to examine how GPS changes relations between cities’ center and margins.

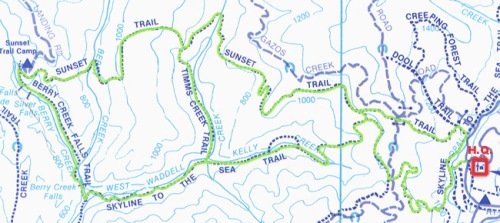

Data visualizations are not present in the recently published primer “Make Map Art” invites us to adopt traditional cartographical tools as helpful strategies to “creatively illustrate your world.” Mapping has long been rooted in the world of graphic design. But the siblings Sue Swindell and Nate Padavick’s Map Art invite readers to embrace the diffusion of mapping as a form of making in the service of self-expression in this lovely book–whose championing of the hand-made map seems a counter-strategy to the near-ubiquity of Google Maps on hand-held screens and maps in evites, embedded in social media, that direct us to a destination. The toolkit offered readers of Make Map Art invites us to adopt tools and forms of maps not only as orienting tools but instruments of “creative illustration” that suggest we rehabilitate forms of mapping as our own tools. These maps are marketed more as a hobby than a strategy of resistance: but in their romanticized vision of the self-made map, a sort of trickle-down of the popular resurgence of hand-drawn maps, they neglect the diversity of spatial knowledges in their “creative toolkit” of easily mastered tools of design. The handsome how-to book offers some twenty projects by which to frame cartographical interventions in a world already abuzz with maps: but the forms of mapping 2-D toolkit primarily marketed in stationery shops and bookstores neglect the most interesting ways cartographical design has caught up with how increasingly stark social divides have come to structure quite divergent perceptions of space.

Web-based maps are not included among the toolkit for map-your-life/make-meaning-from-maps they present, since their medium doesn’t fit the niche audience or the Luddite inflection of the book–or the sense that the map, once considered a tool of government, can be a relaxing way to order space in a world where we are all too often confronted or running to consult a handheld screen. But this might be unfortunate. For in a culture where we are consulting or faced by screens in the forms of attentiveness data-driven maps create compelling models for charting our occupation of space and indeed processing our own relation to space in particularly creative ways. If the screen often provides compelling tools to grasp our increasingly uneven occupation of space to a degree of visual attention unlike–although not foreign to–static maps. They can show us how we fill space, and how our experience of place is redefined with a rapidity that the static design of a local or regional map has difficulty continuing to fulfill its orienting functions. We are impoverished by circumscribing our access to a full range of mapping forms.

In their engaging how-to book of personalized map design, Swindell and Padavick offer a something like a basic toolkit for those eager to respond to fears of being dominated by data. In designing customized maps, one might resist widespread concern for being regularly mapped by unwanted forms of surveillance, and indeed dominated by the ways in which our lives are regularly mapped. But Padavick and Swindell don’t push back that hard: they dwell in the cozily utopian idealized spaces that any map invites viewers to inhabit. It’s cool to play with our sense of space and abilities to create forms of personal orientation for ourselves or indulge in returning to cut-and-paste type of social media of material design in a DIY guide for fashioning personalized geographies ready “to be framed and displayed as artwork” to gain new decorative status as personalized cartographies.

Data visualizations, unlike static maps, define the networks of interaction in which we have increasingly become enmeshed, tracing forms of inhabiting place that are often illuminating of the complexity of navigating place than they are comfortably reassuring. Map-based data visualizations orient us to the shifting ways we fill space and inhabit our streets, and make interpretive demands on their viewers about how we actually have come to use our space. For while the formats of maps offer cool tools of spatial orientation that remind us of the favorite streets we love–and how we walk across them–if the alchemy of data visualizations remake maps as especially creative tools of engaging with one’s environment, they process our own relation to a built space in dynamic ways, effectively organizing our orientation to space by revealing contours of divergent perceptions of and access to space in cities–spaces that are now no longer easily mapped by public transport maps, grids of streets, or even schools and social services. The patterns that data aggregates are particularly valuable as a tool to unpack the changing occupation of urban spaces, from public parks to freeways to avenues, and to interrogate the practical and real boundaries of known space. And they raise questions, perhaps known to some extent in anecdotal experience, about the increased dependence on GPS to navigate urban space in many drivers of ride-sharing services–from Uber to Lyft–perhaps in distinction from drivers’ familiarity with the automobilistic navigation of city streets.

1. Maps that derive from big data offer particularly versatile tools, in contrast, to visualize the ways that we inhabit space and, by extension, how we travel through it and make it our own: much as flows of information or currency or patterns of immigration, data maps show patterns of collective action that is rarely otherwise aggregated, and help us visualize how we inhabit space in dynamic ways. They present the ability to map a network around both space and place as, indeed, constitutive of both, dispensing with and not adopting a static cartographical frame of reference to describe our relationship to space. The alchemy of data visualizations allows us to illustrate shifting relations between urban centers and peripheries in a map, tracking shifts in the nature of mobility in urban space, beyond a physical plant, but embodying how GPS readings tracked each cab across urban space as they move on major arteries, noting not only their positions over time, but indicating patterns of traffic, shifts in density at different times, relative rates of acceleration and different speeds of travel–all to chart how different dynamics by which the aggregate of cab riders’ experiences across urban space, the access to urban space that the self-selected demographic of cab-riders share, and the areas of cities that remain off their maps.

The dynamic results of such data visualizations provide compelling ways to understand the organization of urban space. And in such lies their attraction for puzzling the existence and resilience of place. “Cabspotting” at San Francisco’s Exploratorium invites us to track cabs as they carry fares at different rates of speed and acceleration across that city’s thoroughfares. The data visualization is designed after the pioneering aggregate mapping of cabs in San Francisco’s streets by stamen design’s Shawn Allen and Eric Rodenbeck, displayed in a gallery setting in 2008 at MoMA, and first designed in 2005 by Scott Snibbe, Amy Ballin, and Stamen design. This “high art” of data visualization was devised as a tool to reveal social, economic, and cultural data about the city in a variety of video platforms, exploiting the ability to download massive amounts of data about city cabs in aggregate that could be graphically condensed to a single image of apparent simplicity that spoke volumes on space use. “Cabspotting” (2005) created an innovative alternative model of revisiting the city as a permeable and open space that was at the same time structured by economic patterns and social divisions in urban space: the famous visualization of how people use cabs to inhabit urban space re-envisioned the city’s physical plant in a dynamic data-driven pattern varying trail length in response to cab speed. Its particular power as a data visualization lies in its tracing of a collective iteration of individual itineraries, whose line thickens as they accelerate, creating an image that asks viewers to cathect to real routes through and across the city–either in an aggregate view as below, or in a real-time film of the routes and speeds on which cabs move.

We are able to enter into the pathways along which the city plan is traversed and experienced, as well as occupying an Olympian point of view.

The sinuous traces left by the aggregate of cab-fares allow us to watch cabs moving at different velocity and acceleration across the city, to reveal a haunting socioeconomic X-Ray of the city’s space, and pathways within in its streets. While omitting large areas of poorer regions, from Hunters Point, Bayshore, or Daly City, it illuminates areas in the financial district arrived at with disposable income: thick lines of rides near the shores show a general acceleration, especially on the Central Freeway, Market St., the James Lick Freeway or the 101 and 280, as well as along the Bay Bridge and out to the Airport, reveal a dense distribution of cab lines filling the city plan that hinges on Market Street. The absence of a network of freeways built within the city seems to have helped cabs’ circulation, but cabs are limited to a dense occupation of downtown streets. Indeed, if the sort of freeways and highways were built over and across the space of San Francisco in the way that they were in other cities, perhaps the illumination of that gridded downtown would be less prominent in the Stamen visualization–although one can still discern the 101 or James Lick Freeway and Marina Boulevard leading to Ghirardelli Square in the Stamen map, imagine the shifting spatial spread in a city defined by the proposed arterials which would have rendered the city more navigable, but faced such intense local opposition that they were never in fact built or got beyond the drawing board.

The animation of traffic around San Francisco’s roads and freeways that Cabspotting celebrated the unique space of San Francisco’s streets, removed from a world fearing surveillance. It also provided a model for processing data from taxis to illustrate the ways we use cabs to inhabit and navigate a city’s streets, emphasizing what routes cabs take and how San Francisco’s urban space is navigated, by taking up the perhaps oxymoronic proposition of surveillance technology as truly inspirational, in Scott Snibbe’s phrase. The resulting graphic illuminates a hidden geography of how San Francisco is experienced across time in cabs, whose tracks trace a socioeconomically differentiated space in ways that cast the city’s physical plant in a dramatically new lens, where the density of downtown peters out to wisps along those avenues where fewer cabs run their fares: Cabspotting set a compellingly high bar for data art.

The compelling portrait that emerges from the Stamen visualization offers of primary routes of cab entry generated considerable excitement for a virtual palimpsest of how urban space is navigated by paying customers in a city on a single day. In ways that privilege specific areas of the downtown, and the larger streets–around the bay near the Embarcadero, down Geary Street, along Mission Ave. or nearby Civic Center, it suggests a living template of the city, noting each cabbie’s trajectory of driving by a white line, and increasing the size of its ghostly white lines by velocity and frequency of cabs. As a form of GPS-based art, the ghostly image of the city may have shaped Jeremy Wood’s use of GPS in 2009 to track his personal cartography in the Gliclée print “My Ghost”, imaging an overlay of his own itineraries over the span of a year, but Wood’s image lacked the richness of wealth implicit in Stamen design’s data overlay. Even if it suggested the lack of access of certain areas of London to Wood’s experience of the city, and a wide wandering over a hairy looping of space, the individual migrations through London streets suggests restless iteration of an individual across city streets, unlike the densely packed social clustering of cabs concentrated in the downtown San Francisco and accelerating along freeway lines.

The image Snibbe and Rodenbeck designed offered a memorable real-time contours for a city’s urban space that show a far less dispersive wandering around the vagaries of urban byways, and a focussed repetition of routes around a relatively restricted urban grid. In each of its successive animated time-lapse iterations and real-time rehearsals, the Stamen’s “Cabspotting” re-mapped urban space by tracking the collective aggregate of motion across urban space, using data from embedded GPS data of position, speed and acceleration to remap a strikingly plastic living urban landscape in dynamic–if haunting–ways: pay-per-fare riders sculpt streams of traffic across its major streets and thoroughfares, rife with cab rides, appear illuminated by the aggregated overlay of rides over time, showing the different rides of the city that were being performed as if to condense a residue of the collective transit through the city around select hubs and thoroughfares of increasing or diminishing traffic.

2. The wealth of data mediated by GPS measurements allows one “map” space around each of the “lines” that designate cab-rides by relative speed, using red to highlight moments of acceleration at a fixed period, in a time-lapse moving image that traced the matrix of the city’s streets. In ways that predate but prefigure the current rise of on-demand smartphone-based apps as Umber or Hailo which aim to displace the local cab economies in most metropoles, the pulsing traffic of animated tracking of taxi-cabs renders the city’s grid in a wonderfully dynamic way: Cabspotting serves to delineate clear economic patterns and socioeconomic points about how different folks perceive the same space of the city. The dense glow of traffic around Union Square of cabs parked, circling, or just stationary reveals a center of commercial congregation.

Such tracking of cab-traffic of course may sharply differ in other urban spaces, where centers or commercial districts are more concentrated or differently distributed, and access to space less clearly privilege distinct thoroughfares. The real-time tracking features of Cabspotting liberated static models of mapping by using GPS to amass data in ways Rodenbeck and Allen could readily visualize in clean lines. But the “snapshot”-like nature of the Stamen graphic led to some early envy in data visualization, as Kottke and folks on the East coast imagined what a similar data vis of taxi flow for midtown New York would look like, and first obtained the GPS data from taxi trips to create an image of the “vital signs” of where cabbies picked up their fares in the first half of 2009.

The resulting temporal condensation of an animated sequence of cab traffic between January to March, once sped up to suggest something of a regular flow over time is clearly made to appear synchronized with human cycle of breath, as if to suggest its record of the vitality of the city’s traffic, with fares increasing from 7 am to 8 am, expanding to their highest density in midtown every morning, pausing, and rising again, only to decline in their yellow-hued intensity by nighttime, and leave the city blanched in the early a.m. hours. (The maps should be looked at by anyone interested in hailing a cab, and as a companion piece to the guide of NYC cab etiquette–asking cabbies “What route do you think fastest?” “instills trust in the driver”, rather than giving directions on where to go–although it is unable to be accessed in real time.)

This apparently anthropomorphic time-lapsed image created suggests the inexorable daily constriction and dilation of the city’s vascular system, in tempo with the gorging of taxi fares that slowly dissipate, as if in a forced analogy for urban vitality: the density of fares in midtown suggest clots more than flow, but provided a neat heat-map of city traffic’s frenetic pace. The distinct flow of cab traffic responds to the dense layout of Manhattan, and the saturation of the midtown and lower Manhattan with cab rides that fan up and down its major avenues. Unlike the smooth flows out of arterials and to the outer edges of San Francisco, the knotted nature of the New York City visualization suggested a rigorous diurnal rhythm of relatively small trips of privatized transport, densest at the city’s midtown hubs, and reaching over to its wealthier east-side avenues. But while its anthropomorphic form may be stretched as a bridge fusing nature and culture, the map reveals in important ways the individual specificity of taxi patterns within an urban topography, and indeed the specific diurnal fluctuations that define the demand of taxis–fading as we approach uptown above the blip of the 79th street subway lines–and suggest distinct rhythms of distributions and concentrations of demand for cabs that appear across each urban space, focused in midtown below Central Park, along Broadway and Third Avenue, and specific spots in lower Manhattan.

The specific density of midday midtown reveals a complicated geographical picture a city served by experienced drivers doubtless working in tandem with a sense of its rhythm, best able to gauge the shifting traffic contours of urban avenues.

This image, if interesting, has been recently refined in a two-color data visualization that refine the image of how New Yorkers enter and exit from taxis to navigate New York’s urban space.

3. Eric Fischer re-mapped a specific topography of ‘cabstopping’ by aggregating the range of cab hailings (blue) and destinations (orange) across the city in 2013. And an even more massive amount of cab data was declassified after Chris Whong and Andrés Monroy used New York City’s Freedom of Information Law to obtain a copy of the taxi records from 2013 they soon published on the web. The big data of some 187 million geo-located cab-rides inspired transportation visualization guru Fischer to map the aggregate of total rides taxi drivers gave passengers across Manhattan’s particularly packed automotive space, now on Map Box, in a striking visualization of the collective use of cabs across Manhattan. The map’s strikingly clear block-by-block topography is of striking precision; it illuminates how densely cabs are concentrated in midtown Manhattan and how specifically the vast majority of pick-ups and drop-offs center in specified regions–and how omnipresent are cabs up to Columbia University and 96th on the East: cab-density, unsurprisingly, is a measure of socio-economic wealth and property value.

The social topography of the city is balanced by the white skein of veins in midtown that define a special density of cab-use along major traffic arteries. And it presents one way of mapping a changing configuration of center and periphery across the city. For Fischer, a fan of both crowd-sourced mapping and urban transport system, dissected the data in visually compelling ways by highlighting the starts of taxi rides in blue and the end-points of destinations in orange, a spectrum that allows us to map the topography of collective cab-use around Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens. The demand for local usage of cabs isn’t divided into analytics, but provides an image of the density of cab-use in an actual topography before folks like Uber or Hailo threaten change its face–and seem to use their own GPS tracking to exploit by a smartphone app to connect passengers with vehicles of hire, provoking some concern about using GPS to charge fares, and adjusting fare rates in relation to the density of traffic flows: indeed, the apparently clear preference of New Yorkers to use Uber in off-peak hours and geographically removed and less-served locations suggest that Uber might, in New York, be better conceived as complimentary to the apparently engrained services of other cabs. Are such drivers even more dependent on GPS to discover the relations between fares’ destinations and the cityscape, as well as to find their next pickup?

The data that maps coordinates for the start and end of cab rides provided a way to “map” what places New Yorkers are most likely to hail a cab–perhaps the most difficult places to get a cab, but also no doubt those areas where cab-drivers aware of an increased demand–as local knowledge of cab-riding more informational of urban space than even the most comprehensive transit map–and perhaps augur the life-span of cabs in the age of Uber. It also offers a readily accessible instance of open data which provides a nice counterpoint to the banality of the Google-Maps-based cityscapes that feature on demand cab-hailing apps: or the difficulties for the sophisticated software that sets its rates in relation to the hours of increased intensity to offer what an actually accurate image of the urban space in which it promises travel.

But let’s return to the subtlety Fischer’s coding of end points in orange and sites of hailing in blue allows. The aggregation is so dense that it defines the entire street grid. Most superficially, a scan of the data visualization he posted shows the hailing of cabs to be clustered on avenues where cabs congregate and course North or South–joins legibility with aesthetics, charting where New Yorkers access and stop cabs to tell us a lot about the navigation of the city’s grid in its crowd-sourcing of automotive itineraries.

For Fischer’s visualization deserves plaudits for elegantly synthesizing an exact visualization of the unique ways that folks use urban space: of the over a million and a half taxi-rides that were taken in 2013, most concentrated in the cab-mecca of Manhattan, most seem to be taken along the North-South axes of the avenues, somewhat predictably, with a striking density of destinations on almost all of the major streets, often ending along North-South avenues. Fischer’s map almost illuminates the grid of city streets in ways that tell us considerably amount the range of disposable income available to Manhattanites as well as to most visitors to New York. The intense activity that the cab occupies as a sort of “second car” and mode of transit suggest a fully served community, if it sacrifices data on speed, acceleration, and delays that might be necessary to really envision drivers’ relative effectiveness.

4. Access to this huge data offered a rich vein of data for Fischer, a data artist who often sources huge amounts of information off Twitter, to work characteristic visualization alchemy in a static spectrum to conveys the dynamics of how people move in patterns to organize urban space. While the image is 2-D, the fading and clustering of its range of illumination invest the Manhattan grid with an illusion of three-dimensionality by using a simple set of primary hues. Indeed, the phosphorescent blue taxi pick-ups create indelible records of where the cabs were “spotted” and used, although something of a patina in this digital visualization is created by shimmering “GPS-static” in the more densely built skyscrapers of the city, which are odd artifacts of the mechanics of data collection: as Fischer notes, in certain spots, GPS signals have reflected off buildings’ windows, in ways that add an other (if not welcome) layer of legibility to the map of the city’s space. (Far crisper contours of cabs’ signals arrive from streets that service the much lower-lying buildings of Brooklyn or other boroughs, even if cab-traffic there is far less intense.) We can read the data visualization to detect the conscious choices of cab drivers to negotiate the flows of urban traffic, even though the image is static, based on the similar clustering of overlays in data. Although midtown is somewhat filtered beneath a gauzy layer of interference or blur of GPS-signals’ distortion, as is much of lower Manhattan, reflecting the interference created by urban canyons of clustered skyscrapers that render GPS reception less precise–though we can see the white heat of cabs hailed or congregated at businesses and hotels that serve as sites of conferences and conventions, and detect a temptation to leave rides on East-West streets,as on Central Park South and 57th Street:

The data visualization charts the tacit mechanics of the topography of cab use, by using a orange-blue color differentiation to set of regions where destinations dominate cabs hailed or flagged and journeys begun, and where they leave passengers. We can see a sharp preference to take cabs to destinations on East-West streets, negotiating a topography of traffic that taxi drivers’ familiarities with the different velocity in the white-lit larger avenues control. In contrast, the specificity of red bulbings of destinations at various crosstown blocks where passengers stopped cabs suggests a specifically situated transportation midtown, even with clear evidence of the blurriness of GPS-interference. (GPS fixes are also less easily held near LaGuardia airport, as bright red “worms” approach the access roads of terminals, as if to indicate “premature” arrival of a cab stopping before where they were surely headed; a pattern of blue blurs result that seem air-brushed, in comparison to the crisp lines in Cabspotting.)

If the Bay Bridge stood as a beacon of taxi density in the Stamen visualization of San Francisco, La Guardia seems a brightly burning beacon off Manhattan, and the Brooklyn Bridge provides a lighter but indelible tie recording of inter-borough taxi traffic.

The traffic patterns recorded in the visualization reveal a palimpsest that demand interpretation of denser lines of red (where cabs leave folks in the city) and a tool to investigate how city space is used and what neighborhoods visited per annum:

Red lines are veins across New York City’s Central Park, where one can’t imagine the destinations are actually along the crosstown lanes of traffic that run on paved roads across the park, where tunnels that cabs run through seem to have interrupted the GPS signals as well at 86th street, 81st Street, and 66th:

Brightly lit blue lines illuminate 5th Avenue, a street almost always crowded with cabs, and light up both lanes of Broadway, in ways that offer a beautiful visualization of the way we demand to be driven in Manhattan’s urban space and across its street plan that demand to be pored over with a magnifying glass in hand to best interpret its elegant aggregation. The map can help us create a better navigable urban space–and perhaps respond to the needs for taking cabs in the city–by mapping needs of public transit, and the readiness of customers to use cabs to navigate urban space. The street plan provides tons of neat points about the nature of collective behavior, as all aggregated data, nicely foregrounded in Fischer’s color scheme: just as we detect bright blue sites of starting cab-rides near the Brooklyn Bridge, if considerably brighter in Manhattan, and notice bulb-like orange clumps of drop-offs in Dumbo–the downtown municipal buildings are the looming black blocks.

The blue bulbs at street corners give a more likely (more convenient and better) place to start one’s cab-rides in Manhattan, as our GPS lines bulb out at centers of cab-hailing at intersection in the form of a Q-Tip, suggesting considerable refinement of the data, in spite of the occasional blurred reception of GPS signals: some corners burn an incandescent blue.

5. The specific transportation needs that taxi cab services supply suggest a distinct manner for negotiating urban space at a pace that public transport can’t provide, and a particularly resilient form of a local economy. How might this relate to the specifics of the survival of the cab as a viable vehicle and model of transportation (and the regulation under which cabs function)? In an era when GPS’ing pickup locations in the crowded downtown by Uber threatens the cab-drivers who have so long made their livelihood in the city’s streets. It awaits to see how the density of cab traffic already available in the city will react to the influx of passengers with handhelds.

Indeed, despite the universalizing nature of Uber’s intentions, the app they offer may best function precisely in those cities and urban areas which fit the traffic patterns specific to San Francisco most closely. San Francisco, the city where the app was first devised, offers a unique problem of navigation for taxis: pedestrians and inhabitants both face a scarcity of free cabs and often face the need for long trips from downtown to, say, the Inner or Outer Richmond or Pacific Heights, call cabs over to the East Bay, and are often located at a distance from taxi stands, and where fares might have too much difficulty hailing a cab at later hours. And where single women who want a secure ride door-to-door make up, it’s been suggested, a major portion of the fares. (It might be argued, however, that the whole point of Uber was to harvest a huge amount of data that can be plotted by future mapmakers and indeed predict the relative likelihood of destinations across the city in a more sophisticated way than was ever possible.)

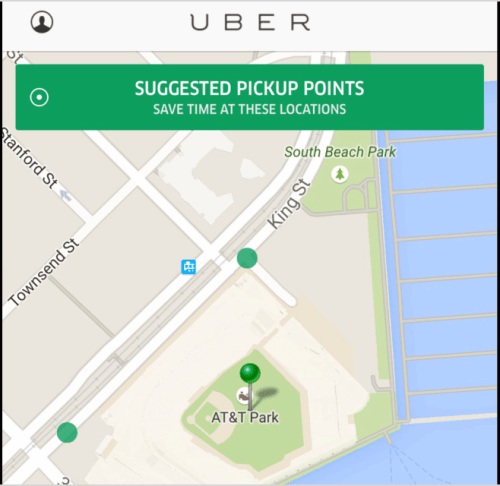

But even in San Francisco, it bears noting, the recent introduction of “Pick-Up Points,” or recommendations of specific pick-up locations in mid-2015 suggest a new way of mimicking mobile taxi-stands for their users–as if to acknowledge the difficulty inherent to promising mobility for an urban space that is often by definition clogged. Although the potential to be anywhere–or assign a driver to appear anywhere–at first distinguished Uber’s provision of crowd-sourced drivers, eerily soon after the suggestion that the rideshare service provide precise locations of where a fare might be best able to draw drivers–and, if not hail a cab, meet one’s driver–the urban maze of U-turns, changing traffic flows, one-way streets and freeway onramps makes it not only more convenient but more enabling to imitate the interactive suggestions made by Lyft, for example, in inviting its users to indicate where they might best meet their ride:

The innovation is not to become less interactive, but to offer a set of coordinates from, for example, a crowded field or region, where one’s ride might otherwise have difficulty locating you, even if that selection may sacrifice the illusion of being anywhere, anytime, and involve some extra footsteps of one’s own:

There is some data that demonstrates that the indication of such exact sites of pick-up may allow riders to appear at precise times without creating a situation where drivers would actually compete for fares, and to ensure the illusion of personalized service in a service that in aggregate reveals clear patterns of its own.

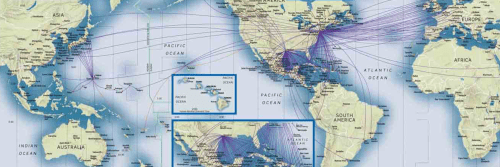

The harvesting of data that Uber allows, indeed, makes it a sort of Google for the taxied set, and creates something like a valued dataset that Uber has done its best to exploit. As Bradley Voytek has noted in a neat on the Uber Blog, in a neat weighted diagraph visualizing the flow of rides from one of San Francisco’s neighborhoods to another, noting the aggregates of rides leaving a neighborhood by a circle of varying size and drawing weighted arcs in the color of the neighborhood of a destination, the flow of Uber rides predominantly originate from South of Market or downtown–the largest point of departure of Uber clients by far. Almost all the rides originate from the downtown. This clustering of rides around a single region of the city suggest a restricted range of sites of departure for on-demand rides, and a marked clustering among three neighborhoods from which users predominantly originate–although it should be noted that Voytek used dated data rather than the data Uber now possesses–and offers a larger visualization here.

Might one decide to map the different topographies of traffic flow across different cities in the hopes of predicting how well Uber offers a fit for the navigation of a distinct urban space? Even with the increased homogenization of cities, the underlying plans and patterns of local traffic provide some guide to its potential “fit” with local traffic and cab-use. It demands investigation how the market would adjust for Uber to be most complimentary to local needs. The integration of GPS with a local taxi economy has been recently argued to create an artificial scarcity of taxis squelching competition, but to champion the free market approach runs the risk of setting off shocks in the local economy of providing short-term rides that has developed in the city’s somewhat fragile transportation economy. For as well as reveal the pathways of negotiating urban canyons of New York, the visualization reveals a delicate local economy in which car-users navigate the available calculus of transportation–a city where few drive the cars they own every day, and despite a relative density of car-ownership in Manhattan and New York City as a whole.

Indeed, many don’t even rely upon cars–despite the incredible density of cars per square mile in the relatively affluent region, according to the data mapped in StreetsBlog LA.

Viewed another way–vehicles/person–New York City seems relatively low-density, indeed, because of the sharp contrast to outlying “suburban” areas or peripheries: few cars are used for commutes, and multiple car ownership is quite rare. Reasons for owning vehicles shift in different social topographies.

The stark contrast in the regional distribution of statistics of car ownership are striking on the micro-level of Manhattan are indeed evidence of a large commuting culture, where many cars belong to commuters who live in more car-friendly lands outside the five boroughs:

Although the vast bulk of cab-rides in New York City are based in downtown traffic, where garages are costly and urban street space at a premium, the data visualization reminds us of the continued importance of cab services to negotiate local space. The relatively subtle tool for moving in a narrow time-window that cabs provide offer an increasingly needed medium to move through and use space that seems unwise to disrupt not only as a way to move the city’s economy, but for the very reason that it is so deeply established of negotiating specific constants of its traffic patterns and laws. Indeed, the poor ability of GPS or any GIS system to record the shifting pulse and intensities of traffic raises questions of the time which its drivers need to accommodate to actual traffic flows.

If Uber is able to navigate it, best of luck. Maybe it already has: but the uncertainty of how markets are currently treating this ride-sharing service suggests that it may have opened the way to far more competitors than it ever foresaw.

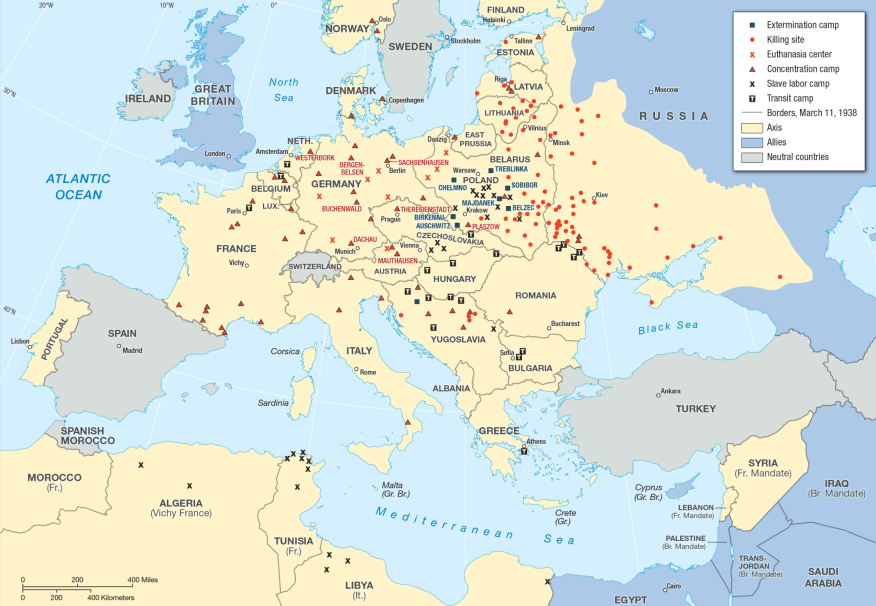

aBefore these maps of spaces of dehumanization and devastation, we are really looking into hellish worlds we had not been able to see before. But even these dots cannot capture the scale of the hellscapes that emerged for the accelerated loss of life within the industrialization of death that proceeded from Heinrich Himmler’s order of 19 July 1942 stated that unleashed mass-killings from bullets, fire, and gas extermination to fullifll the demand that by the end of December 1942, all Jews, gypsied in Greater Germany be killed, leading to an unprecedented intensity of rates of mass-killings almost impossible to map on paper or by a graph, challenging as the spatial dynamics of the three-month long burst of killings is poorly documented–intentionally–and

aBefore these maps of spaces of dehumanization and devastation, we are really looking into hellish worlds we had not been able to see before. But even these dots cannot capture the scale of the hellscapes that emerged for the accelerated loss of life within the industrialization of death that proceeded from Heinrich Himmler’s order of 19 July 1942 stated that unleashed mass-killings from bullets, fire, and gas extermination to fullifll the demand that by the end of December 1942, all Jews, gypsied in Greater Germany be killed, leading to an unprecedented intensity of rates of mass-killings almost impossible to map on paper or by a graph, challenging as the spatial dynamics of the three-month long burst of killings is poorly documented–intentionally–and

.

.