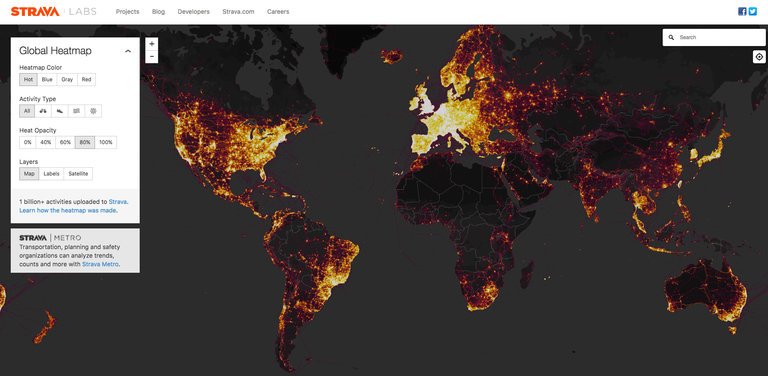

Was it only a coincidence that on the eve President Donald Trump boasted in his State of the Union address of an era “we no longer tell our enemies our plans” that the release of a live global heatmap pinpointed the location of U.S. military installations? The release by Strava Labs of a spectacular heatmap that celebrated the routes where folks exercise worldwide suggested the flows of itineraries of physical exercise by running, biking, or skiing in stunning lines to reflect increased intensity, that appeared as if engraved on a dark OSM base map. Indeed, the open nature of the data on military positions offered to any viewer of the heatmap seems as pernicious as culling of internet use long engaged in by the NSA, but for the state–as well as for the safety of soldiers who share their location, or fail to use security settings, as they exercise while completing military service abroad. Is this approaching a new level not only of broadcasting plans to an enemy, but failing to protect military positions in internationally sensitive zones?

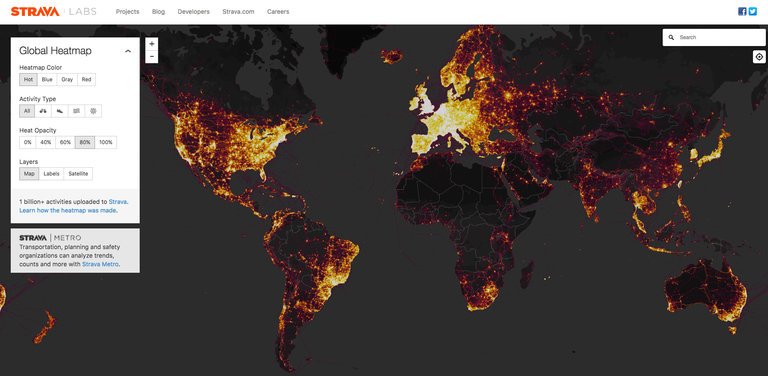

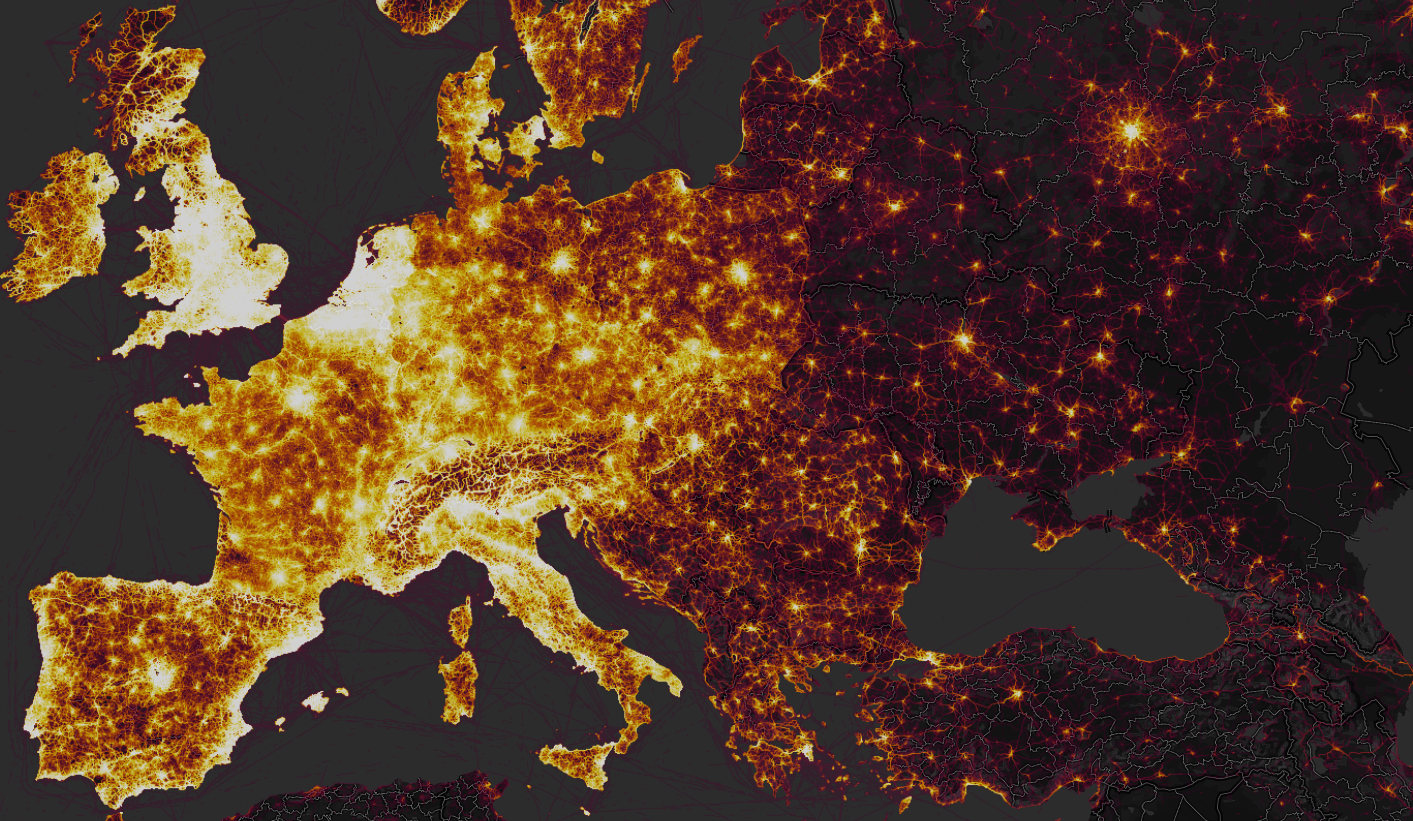

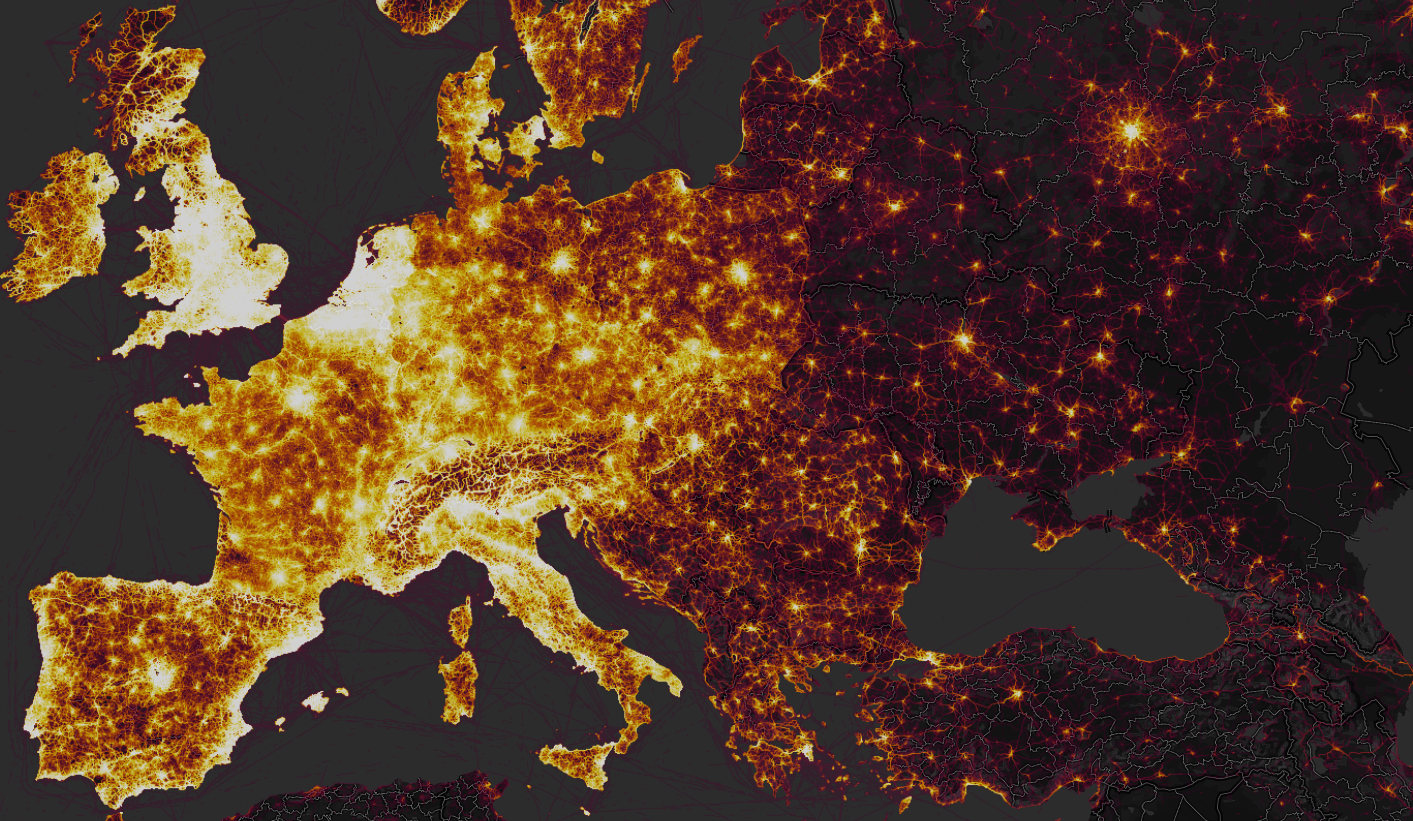

While the map had been around for several years, its detailed update was so much more comprehensive than the 2015 version included–and was released in a time when internet observers scrutinize data visualizations. The updated heatmap was a big deal for how it illuminated the world in a ways that few had seen, both in its own architecture of a spectacular network of athletes that reflected its expanded use, and the huge data included in aggregated routes for training, but illuminating clear divides between its users; but it gained even more attention foregrounding the presence of isolated groups of athletic performance abroad with an eery precision and legibility that quickly raised concerns reminiscent of the scale of unwanted intruding or monitoring of physical actives, even in an app that based its appeal in the data density of tracking it provided. While promising individual privacy or anonymity, the benefits promised by the fitness app seemed almost a runaround of the appeal of PGP, Tor, and Privacy Badger that promised a degree of privacy by encrypting data from online trackers and privacy self-defense; rather than ensure the anonymization of the internet connections, however, the platform posted patterns of use whose legibility did not violate individual privacy, so much as state secrets. Indeed, the surprising effects of how the Strava app made individuals suddenly legible so that they popped out of darker regions was perhaps the most striking finding of the global heatmap, as it illuminated stark discontinuities.

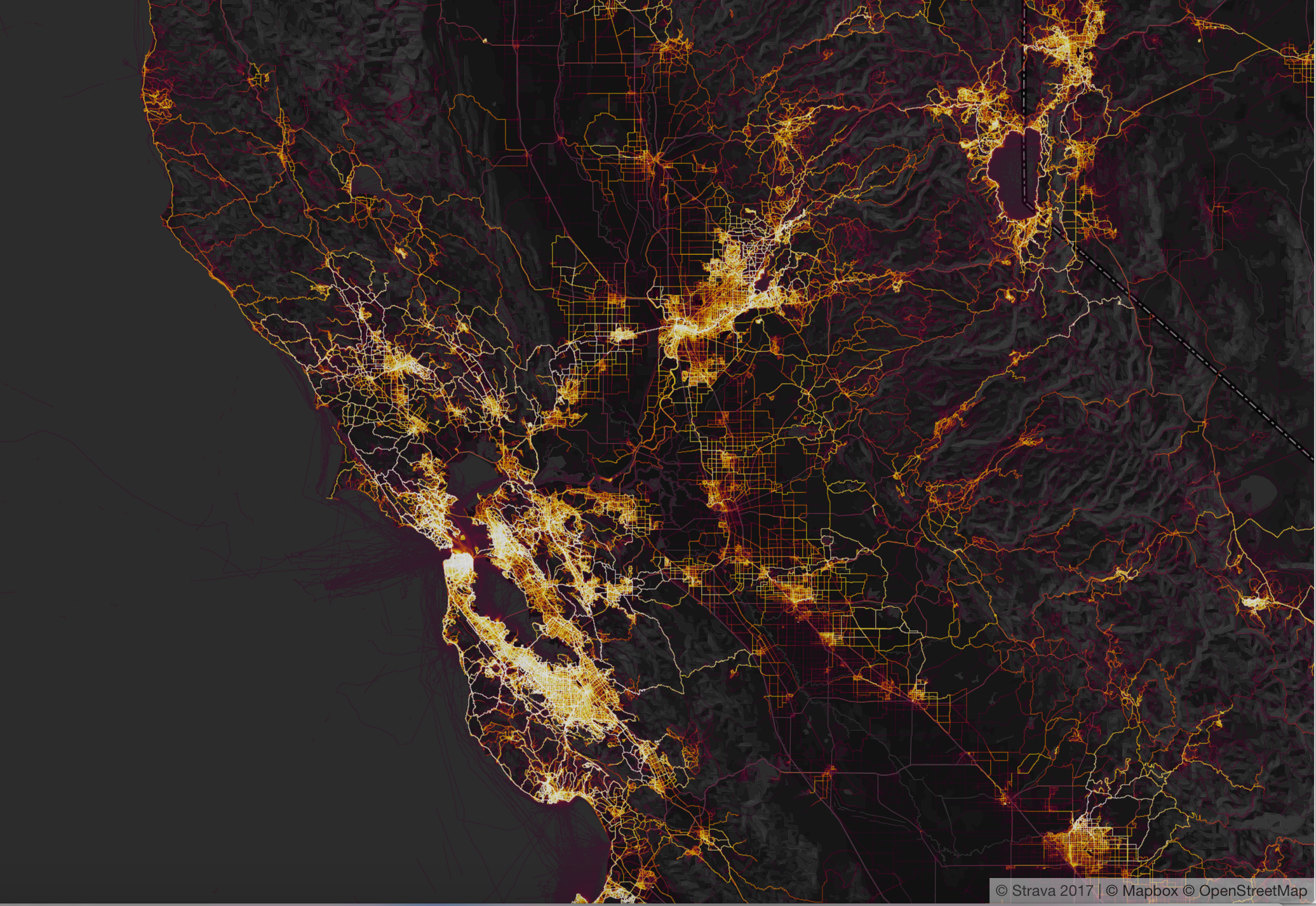

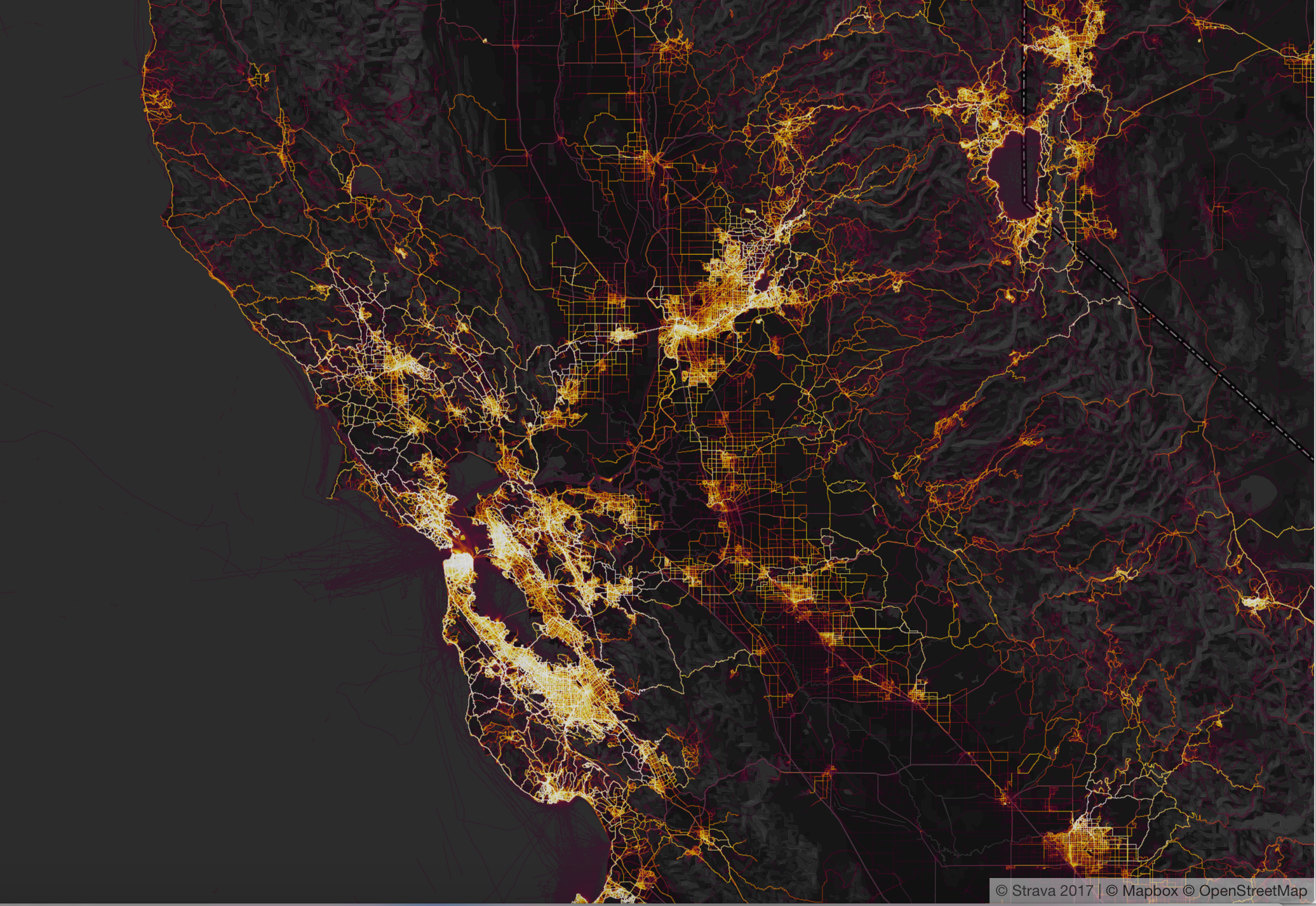

The newly and vastly amplified dataset included zoom functions of much greater specificity: so richly detailed Strava was charged with betraying once secret locations of U.S. military worldwide, even if unknowingly, and creating a data vulnerability for the nation the would have global effects. The heatmap made stunningly visible rasterized images of the aggregate activity of those sharing their locations that it gained unwanted degree of publicity months after it went live in November, 2017, for revealing the actual location and global military presence of American soldiers tracking their exercise and sharing geodata–including American and European soldiers stationed in the Middle East and Africa, and even in South Korea. Although the California-based fitness app rendered space that seemed to celebrate the extent and intensity of physical exercise in encomiastic ways, as if the app succeeded in motivating invigorating exploration of space, and tracking one’s activity that guaranteed anonymity by blending data of its users in brightly lit zones, as for the Bay Area–

–the image that had clear implications of announcing its near-global adoption registered in the more isolated circumstances that many members of the American military increasingly find themselves. The data set that Strava celebrated in November, 2017 as “beautiful data” on the athletic playgrounds of the world took an unexpected turn within months, as Strava came to remind all military users to opt out of sharing their geodata on the zoomable global heatmap, that aggregated shared geodata, lest secret locations of a global American military presence that extended to the Middle East and Africa be inadvertently revealed. Whereas the California fitness app wanted to celebrate its global presence, the map revealed the spread of secret bases of the U.S. military in a globalized world. The map of all users sharing geodata with the app were not intended to be personalized, but the global heatmap showed bright spots of soldiers stationed in several war zones.

The narrative in which the map was seen changed, in other words, as it became not a data dump of athletic performance across the world, that was able to measure and celebrated individual endurance, but a narrative of hidden military and intelligence locations, tagging CIA operatives and overseas advisors by indelibly illuminating their exercise routes in a field of war in ways that seemed to foretell the end of military secrets in a world of widespread data-sharing. And Strava Labs for their part probably didn’t exactly help the problem when they took time to assure the public that they indeed “take the safety of our community seriously and are committed to work with military and governmental authorities to correct any sensitive areas that appear” in the web-maps,” as if to assure audiences they privileged the public interest and public safety of their users. (But as much as addressing public safety in terms of operational security, Strava’s public statements were limited to caring for the community of users of the app, more than actual states. The disjunction reveals very much: when Strava labs saw their “users” or customers as the prime audience to which they were faithful, they indeed suggested that they held an obligation to users outside of loyalty to any nation-state, and indeed celebrated the geographical distribution of their own community across national frontiers.) Indeed, the app’s heatmap disrespected national frontiers, by suggesting an alternate space of exercise that was believed and treated as it had nothing political in it.

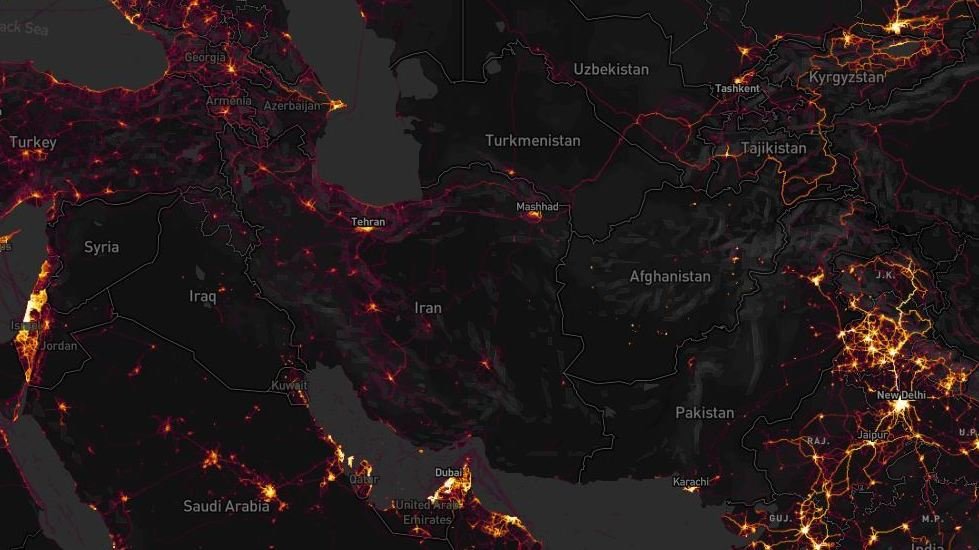

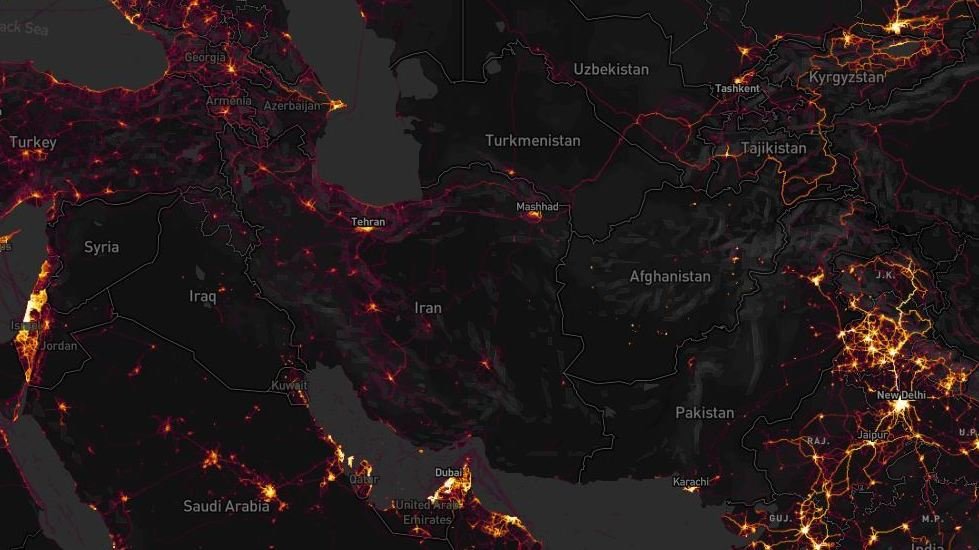

In contrast, the landscape that American President Donald Trump presented in his first chest-thumping first State of the Union returned to the restoration of American security seemed incredibly to deny the consequences of recent availability of military geodata and indeed military base locations, in announcing that in his watch, we “no longer tell . our enemies our plans. For whereas President Trump boasted the return to an era of national security and guarded military secrets, the app broadcast a pinpoint record of the global dispersion of American troops, military consultants, and CIA “black” sites and annexes. Indeed, for all the vaunted expansion of the U.S. military budget, the increased vulnerability of special operations forces has been something that the United States has poorly prepared for, although the release of the heat map prompted Gen. Jim Mattis to undertake a review of all use of social media devices within the military, so shocked was the news of the ability to plot geographical location by the exercise app. If the activities tracked and monitored in the hugely popular fitness app suggested a world taking better care for their patterns of exercise, it revealed scary patterns as a proxy to chart American presence that map the recent global expansion of the United States military in the beauty of its global picture across incandescently illuminated streams–

–as when one zoomed down to those running in Kabul, and geolocated the movement in ways that betrayed military footprint from intelligence personnel to foreign operatives to contractors overseas. The data harvested on its platform appears to endanger American national security–and offers new ways to combine with information culled from social media–as it seems to pinpoint the bases around which military take their daily runs.

Strava heatmap, Kabul

Strava heatmap, Kabul

The recognition of the scale of personal tracking by soldiers sharing data on exercise apps grew as one exploited the heatmap’s scalability, and examined areas in which few locals were using it–or had access to the First World problem of registering how many miles one ran. While the data was not only sourced from Americans, the anonymity of the aggregate map–which can be viewed in multiple shades–provided an image of ghostly presence that seemed particularly apt to describe concerns of security and suggest an aura of revealing secret knowledge. The cool factor of the Strava map lit up the hidden knowledge that echoed the longstanding surveillance of the communication records of Americans in the bulk data collection that the Patriot Act allowed, although now the dragnet on data use was being done by private enterprise, suggesting an odd public-private sharing of technology, as what had been viewed as a domestic market suddenly gained new uses on an international front. The poor data security of U.S. forces abroad reminded us that we are by no means the only actor collecting bulk data, but also the scale of digital dust that we all create as we entrust information about our geographical locations to companies even when they promote the value of doing so to be salutary.

Multiple accusatory narratives quickly spun about whether the release of the new global heatmap by Strava Labs constituted a breach in national security. The soundbite from the State of the Union proclaiming a “new era” described changed conditions by referencing Gen. Michael Flynn’s charge, first raised during the 2016 Presidential campaign on national television news, that the United States had sadly become “the best enemies in the world” during the Obama years, as he attacked the government of which he had been part for being itself complicit in how “our enemies love when we telegraph what we’re doing” by not maintaining secrecy in our military plans. Flynn’s assertion became something of a meme in the campaign trail. And President Trump sought to reference the fear of such changes of a past undermining national authority abroad when he claimed to bring closure to lax security, choosing to message that the loopholes that existed were now closed, and respect had been achieved. The fictionalized imaginary landscape seemed to distract America from danger or unemployment in celebrating its arrival in a better economic place. The message seemed as imaginary as the landscape of an employed America, which had arrived in a better economic and place.

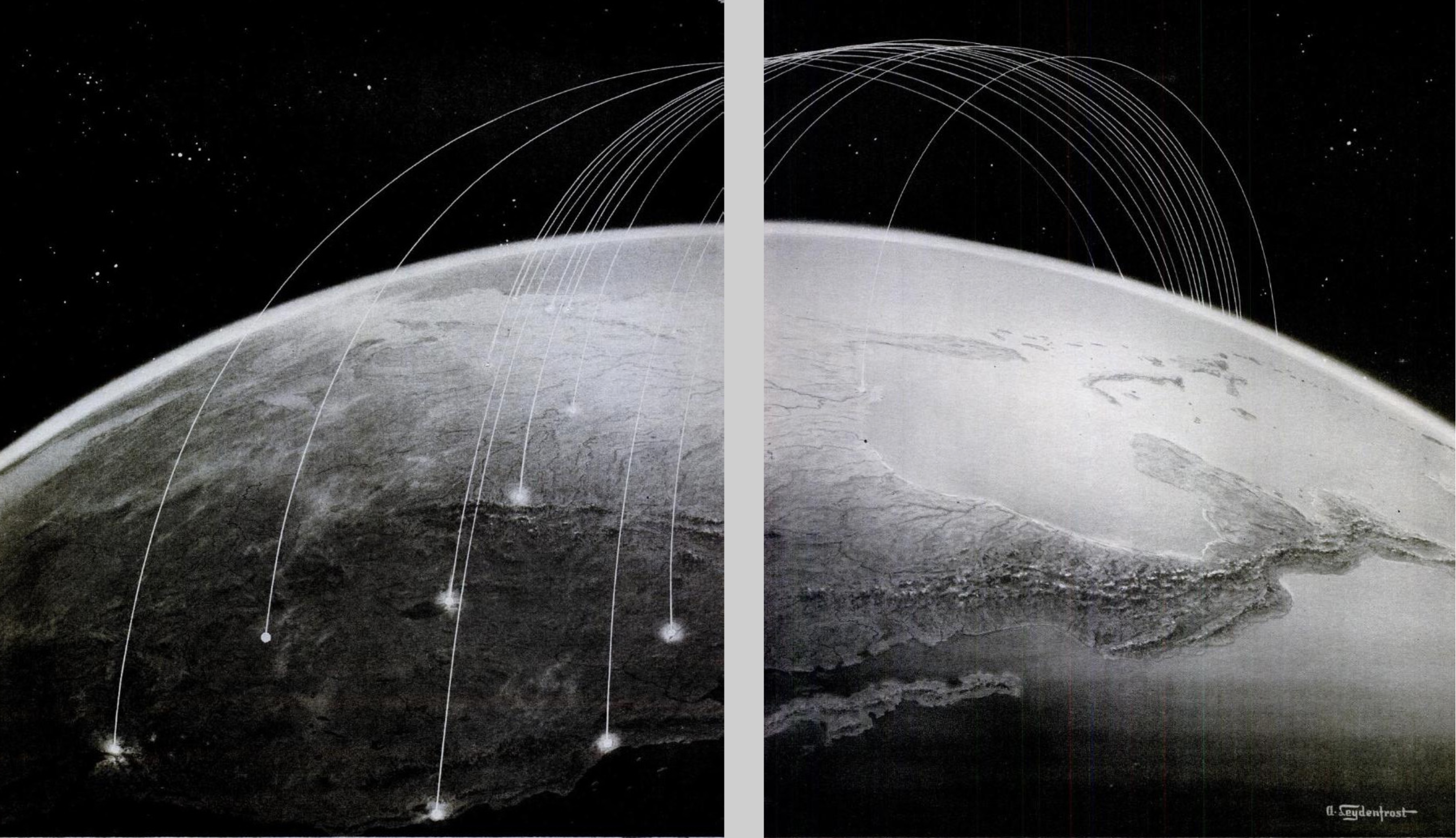

General Flynn’s metaphor of telegraphing was even then quaintly outdated, as if from a different media world. But the allegation that had become a meme on alt right social media during the campaign to discredit military competence, gaining new traction as data security became increasingly a subject of national and international news. Since President, despite having quickly issued one of executive orders that he has been so fond of signing on cybersecurity, Trump has in fact been openly criticized for a lack of vision or of leadership in addressing national vulnerabilities in cybersecurity. As President, Trump has preferred to pay lip service in the executive order, by far his preferred medium of public communication, to the growing frustration of a number of cybersecurity advisors who resigned before clarifying best practices of grid security. Broad sharing of geodata by military and intelligence raised red flags of security compromises; it would, perhaps, be better raise a clarion call about our unending readiness to aggregate and be aggregated, and the unforeseen risks of sharing data.

The patterns of tracking exercise–biking, running, swimming, windsurfing–created striking pictures in aggregate, reflecting the collective comparisons of routes and itineraries, and showing a terrain vibrant with activity. But while the app did not specialize in tracking individual performance or local movements, the new context of many apps transformed foreign counties where military travelled to sites where their data sharing stood out. The sense of accessing the platform was so second nature to American soldiers moved across space, in fact, ignorant of the platform on which it was aggregated and its effects–or the audiences before who it was broadcast and displayed. The ability to detect bright spots of athletic engagement around American bases, military camps, and CIA outposts suggested an unwanted form of data-sharing, RT television newscasters proclaimed with undisguised pleasure at the ease with which soldiers could be observed in different locations across the Middle East, from Saudi Arabia to Afghanistan, to Pakistan, and crowed that Americans are so unwary about being surveilled so as to provide evidence willingly of their own global footprint’s size.

It’s striking that government secrecy has become a public hallmark of the Trump administration. But if Trump wanted to inaugurate the start of a fictional landscape of securing state secrets in his first State of the Union address, his words were pronounced with no acknowledgement of the release of the heatmap and the concerns of leaking security operations. The map that Strava labs designed to celebrate the global extension of a triumphal image of the expansion of exercise in a triumphal image appeared in new guise as the latest example of breached military security secrets–suddenly made apparent at high resolution when one zoomed in at greater scale to Syria, Somalia, Niger, or Afghanistan, and even seem to be able to track the local movement of troops in active areas of war, and not only identify those bases, airfields, and secret annexes, but map their outlines that corresponded to the laps that soldiers seem to have run regularly around their perimeter while sharing their geodata publicly, or with the app. While the app was designed to broadcast one’s personal best, as well as log one’s heart rate, sleep patterns, and performance (personal data which remained private), it collated in aggregate the patterns of activity across national borders.

For its part, Strava had only boasted it could “create the ultimate map of athlete playgrounds” by rendering “Strava’s global network of athletes” in a stunning heatmap from directly uploaded data. If there was a sense that the “visualization of Strava’s global network of athletes” described a self-selected community, the beauty of the data set created from 13 trillion data points provided a new sense of exercise space, as if it sketched a record in aggregate of individual endurance, or a collective rendering of folks achieving personal bests. But the illuminated “maps” of the global network of those exercising and the distribution of US military bases and sites of secret involvement raises complex issues of data-sharing, and the shock at the intersection of leisure space and military secrets–somewhat akin to the stern warning military commanders issued to years ago about using Pokemon Go! in restricted areas of military bases, mapping a comprehensive global map of military over-extension is an odd artifact of globalization. And it was odd to see RT seize on this issue, as a way of describing the presence of the actors they id’d as “Uncle Sam” to suggest how zooming in on the global map revealed the reach of the United States in Afghanistan or Syria, as if playing a computerized game to see where clusters of forces might be illuminated, as if to exploit fears of revealing military secrets through geolocated data.

The story was pitched on RT suggested a market-driven surveillance network of which the Americans were themselves the dupes. In its own spin on the story, RT reported of the leaks with glee, for rather than arriving from hackers, or Russian-sponsored hacking groups, military security was compromised by the very tracking devices, it was argued, that soldiers, military intelligence, and CIA officers wore.

By imposing outlines of national maps on the dynamic rasters of the web map that Strava released, the position of military forces or advisors indeed seemed able to be roughly revealed as military secrets by zooming into locations, much as RT announcers asserted, as if the “bracelets” of fitbits provided tools to geolocate soldiers as if they were manacles, reminiscent of the ankle bracelets given to many parolees, sex offenders, or prisoners, by using a GPS tracking system to monitor released inmates all the better to monitor their acitivities, in a practice that has only grown in response to overcrowding conditions in many federal and state prisons–GPS tracking systems were billed as able to save prisons up to $9,500 per inmate, or up to $25 a day; but rather than provide tools to surveil non-violent offenders, the effective monitoring of military bases and what seem CIA field stations provided a multiple security vulnerabilities of unprecedented scale.

But the real story may have been how so much data was available not only for state eyes, but for a broader public: in an age where surveillance by the state is extending farther than ever before, and when we need, in the words of Laura Poitras, “a practical and metaphorical road map for navigating the post-9/11 landscape,” the maps of Strava have shifted the landscape of surveillance far from the state, and deflected it onto the internet. For the far greater geographical precision and detail of a diverse user group may prefigure the future of data sharing–and the increased vulnerabilities that it creates. The live data map broadcast not only an image of global divides, but of the striking patterns of the aggregation of geodata that reminded us of the pressing problem of data vulnerability in the military’s extended network of secret military bases and dark sites. Indeed, when a student at the Australian National University in Canberra, Nathan Russer, first noted that the Strata search engine created an Op-Sec catastrophe for leaking locations of US military patrols and bases, his observations unleashed a storm of pattern analysis and fears of compromised national security. It indeed seems that the vaunted agility that allowed American forces to deploy in much of the world could now be readily observed, as we zoom into specific sites of potential military involvement to uncover the presence of Americans and assess the degree of involvement in different sites, as well as the motion through individual sites of conflict. The spectral map that results suggests something quite close to surveillance–at time, one can scrape the place of individual users form the app’s web map–but that is dislodged from the state.

The notion of a private outsourcing of data surveillance to the public sphere is hardly new. One can think, immediately, of Facebook’s algorithms or personal data-harvesting or those of search engines. Although the U.S. Department of Defense has urged all active military abroad to limit their active presence in online social media, no matter where they are stationed, the news reminded us yet again of an increased intersection between political space and social media, even if this time the intersection seems more shaped like a Moebius strip. The divisions within a global geographic visualization of Strava’s users reminded one of a usage landscape that suggested a striking degree of continuity with the Cold War–with an expanded iron curtain, save in scattered metropoles–whose stark spatial division reminded us of the different sort of lifestyles that public posts of athletic performance reveals. As much as showing a greater openness, the heat map suggests a far greater willingness of posting on social media use: the intersection suggests a different familiarity with space, and a proprietary value to the internet.’

Strava Labs

Strava Labs

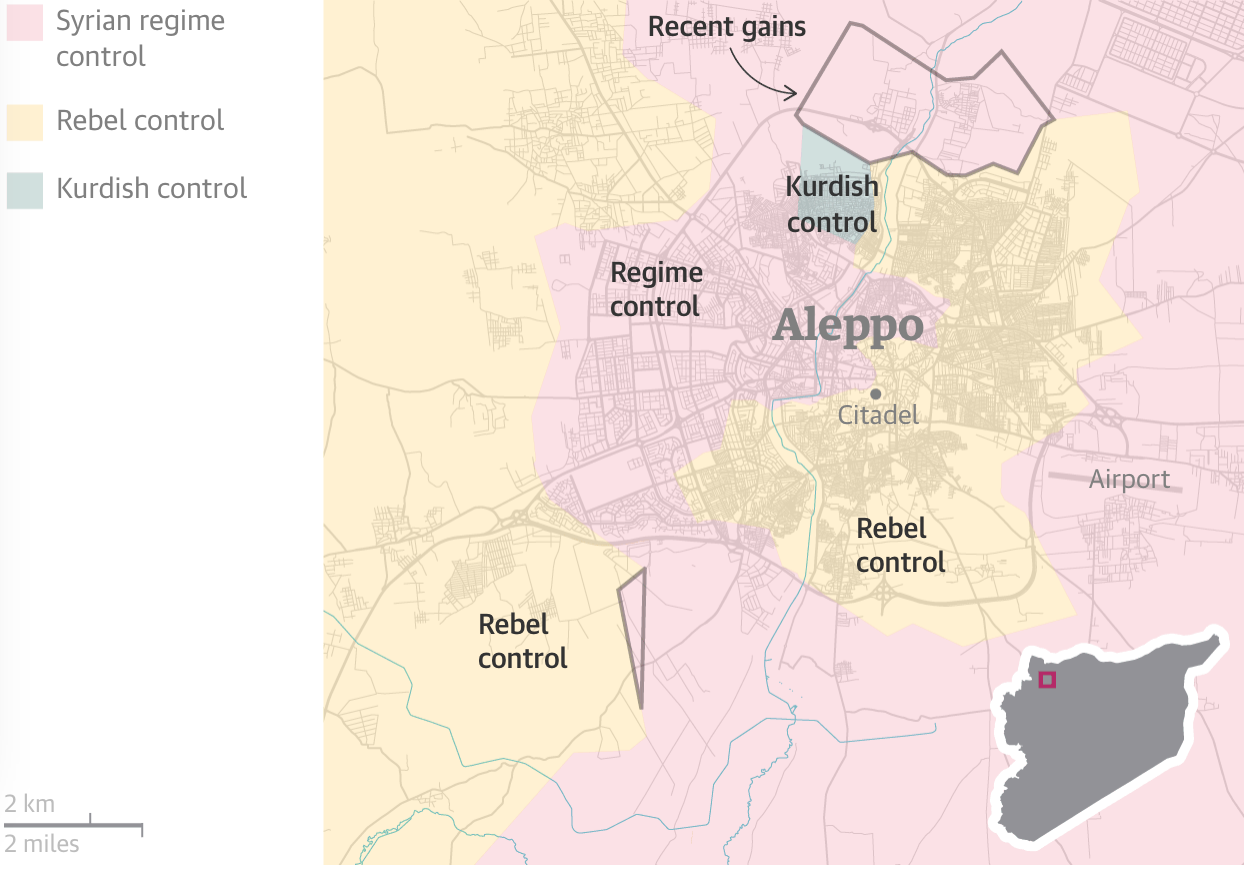

Indeed, in only a few months to notice how American soldiers’ presence in coalition military sites suddenly popped out in the darker spaces of the Syrian Civil War, where different theaters of action of coalition forces that include American soldiers are revealed, and panning back to other theaters can indeed revealed the global presence of U.S. military and intelligence. Against a dark field, the erasure of any sense of national frontiers in the Strata labs data map suggests the permeability of much of the world not only by interactive technologies but by the isolated groups of soldiers who deal with the stress of deployment by bike rides and runs while they are stationed in Afghanistan.

Although the fitness app saw its aggregation as registering geodata in the relatively apolitical space of physical exercise, fears of political and national security repercussions ran pretty high. Indeed, the tracking of running laps, cycling, and daily exercise routines revealed U.S. military bases in Syria so clearly that it proved a basis to locate and orient oneself to an archipelago of U.S. military activity abroad in the global heat map, and lit up American presence in Mosul, Tanff, north of Bagdad and around Raqqa, providing a historical map able to pinpoint airfields, outposts, and secret stations in the war against the Islamic State. Security analysts like Tobias Schneider argued they helped track the movements and locations of troops and even extract information on individual soldiers. In place of an image of the global contagion of tracking exercise, the patterns of performance provided a way to look at the micro-climates of exercise on a scaling that were not otherwise evident in the arcs of the impressive global heatmap.

Sissela Bok classically noted the ways that secrecy and privacy overlap and are linked in some collective groups, as the military, but the absence of privacy or secrecy on much of the Strava Labs heatmap raised questions of the increasing difficulties to maintain a sense of secrecy or privacy in an age of geographically growing war. In an age when more and more are living under surveillance, and indeed when the surveillance of subjects has only begun to gain attention as a fact of life, the fear of broadcasting an effective surveillance of exercising soldiers seems particularly ironic–or careless. The practices of secrecy were more than lax. For the United States military has in fact, quite vigorously promoted Fitbit flex trackers among pilot programs at U.S. bases to lose calories, and provided devices that measure steps walked, calories burned, and health sleep as part of its Performance Triad; Fitbit trackers were provided as part of a pilot fitness program from 2013 with few issues raised about security, and placing restrictions on American soldiers’ use of mobile phones, peripherals, or wearable technologies would limit military volunteers. (The Pentagon has in all distributed 2,500 Fitbits as part of its anti-obesity program, in more flexible wearable form, without thinking of the information that they broadcast.) Yet soon after the map appeared, folks noted on Twitter with irony that “Someone forgot to turn off their Fitbit,” and it became a refrain on social media by late January, as the image that tracked American military outposts not only in Kabul, but in the Sahel, Somalia, Syria and Niger all popped out of a global map–embodying the very outlines of the camps around which military run. ‘

Although the U.S. National Counterintelligence and Security Center informed the intelligence community of dangers of being tagged by “social media postings,” the imagined privacy of exercising soldiers is far less closely monitored than should be the case–resulting in a lack of clear vigilance about publishing Strava data.

Kabul, Afghanistan, in Strava Labs global heatmap

Kabul, Afghanistan, in Strava Labs global heatmap

The heat map so strongly lluminated itineraries users ran, biked, or skied, tracked in incandescently illuminated streams, and even zoom in on specific locations, where they stand out from considerably darker zones of low use of the app, that some national security officials wanted the app to take time to take the maps offline so that they could be scrubbed; worries grew that one could even to scrape the itineraries of individual soldiers who exercise on military service in the heatmaps.

But the two fold ways of reading of the map’s surface suggest that their contents were difficult to free. The same map celebrating the app’s global use revealed deep discrepancies between the brightly illuminated areas of high-use and data input and its dark zones. Data mapped on Strava’s website also seems to enable one to id the soldiers using the Strava app with far greater certainty than foreign governments or non-state actors had before, in ways that would create multiple potentially embarrassing problems of delicate foreign relations. While in part the fear may have derived from the hugeness of the dataset, the fear of being compromised by data raised an increased sense of emergency of a security being risked, and fears of national vulnerability. Partly this was because of the huge scale of geospatial data. The updated version of the heatmap issued by Strava Labs illuminated the world in a way that few had seen, and not only because of its greater specificity: Strava had doubled its resolution, rasterizing all activity and data directly uploaded, and optimizing rasters to ensure a far richer and more beautiful visualization, along glowing lines to reflect intensity of use that looked as if they were in fact vectors. It made its data points quite beautiful, stretching them into bright lines, eliminating noise and static to create a super smooth image that almost seems to update the Jane Jacobs’ notions of public space and its common access–and the definition of spaces for exercise.

To some extent, the highlighting that the app did of common routes of exercise seem to mirrored the metric of walkability, the measurement of active transportation forms like walking and biking and stood as a surrogate for environmental quality. The fitness map improved on the walkscore or its cosmopolitan variants, by involving its users to create a new map of exercising space. The abilities to foreground individual and collective athletic performance in a readily accessible map provided what must be admitted is a pretty privileged view of the world; but the self-mapped community it revealed gained a new context just two months after it went live, as the map drew attention to the patterns it revealed of using an app to track one’s activities, as much as register work-out trails.

San Francisco in Strava Labs Heatmap

San Francisco in Strava Labs Heatmap

The new map attracted attention not only for the fitness crowd, a self-selecting demographic, in short, but as an interesting extension of the beauty and the huge amount of datasets it uploaded and digested in a highly legible form: indeed the legibility of the data that was able to be regularly updated online suggested a new form of consensual surveillance. The data-rich expansion of what was the first update to the global heat map of users that Strava Labs issued since 2015 encoded over six time more data, and promised a degree of precision that was never even imagined before, notably including correction for GPS distortions and possibilities of new privacy settings, in ways that amplified its ability to be seen as a tracking device most notably in those areas where the aggregate of Strava users was not so dense, first of all those military sites where American military and operatives were stationed and perhaps secretly engaged, but gave little thought to the day sharing app installed on their Fitbits or iPhones, and may even have seen the data-sharing function as a source of comfort of belonging to a larger exercise community.

Continue reading →

Strava heatmap, Kabul

Strava heatmap, Kabul

Strava Labs

Strava Labs

Kabul, Afghanistan, in

Kabul, Afghanistan, in  San Francisco in Strava Labs

San Francisco in Strava Labs

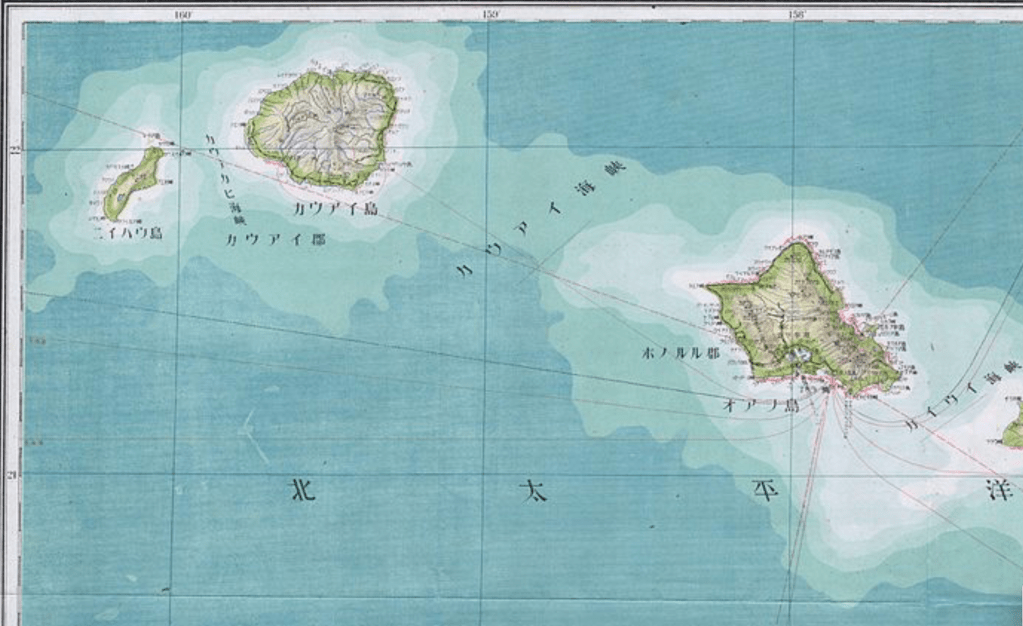

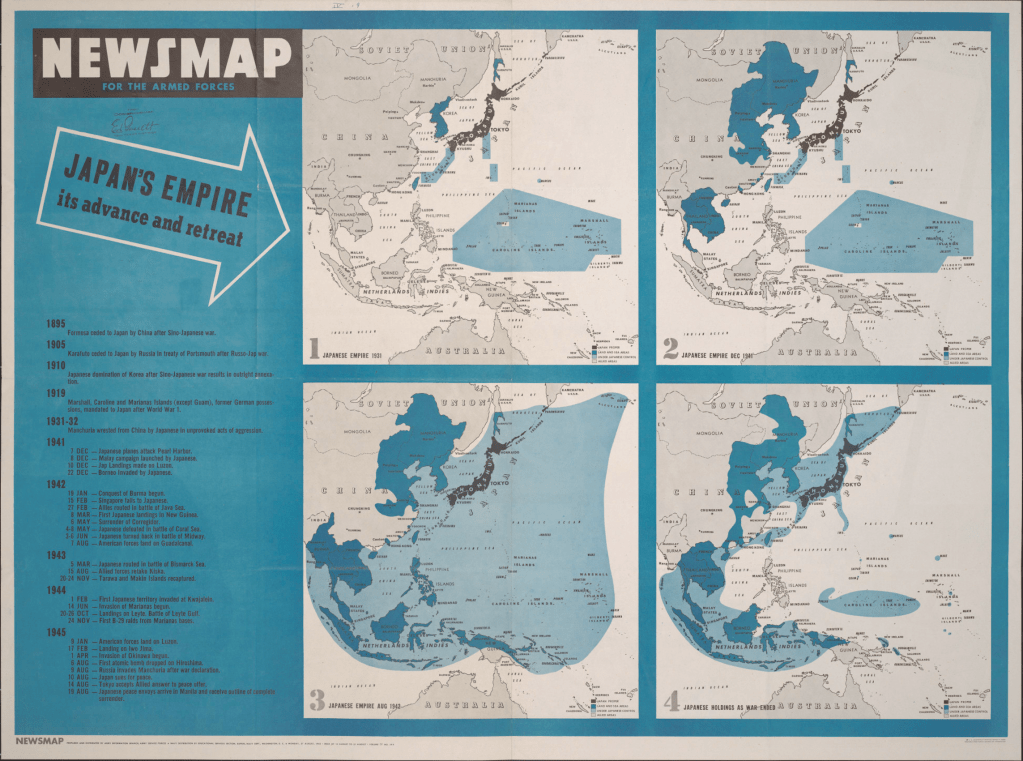

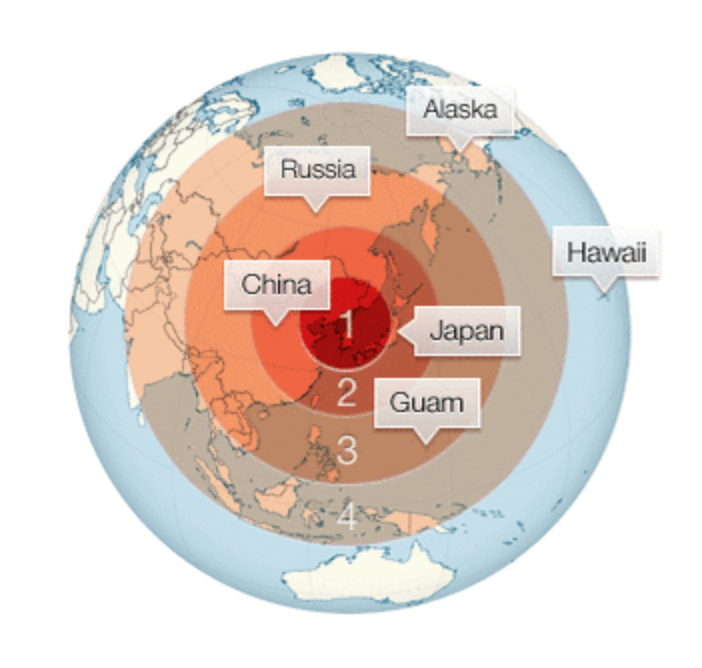

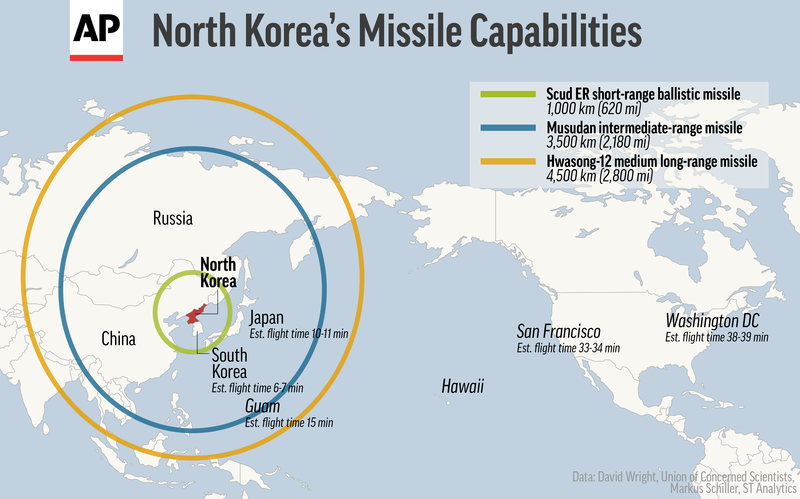

Kim Jong-un studying the flight of the Hwasong-12, which reached an altitude of 1,312 feet Reuters/KCNA (May 14, 2017)

Kim Jong-un studying the flight of the Hwasong-12, which reached an altitude of 1,312 feet Reuters/KCNA (May 14, 2017)

November 1, 2016/

November 1, 2016/